HOME BRAZIL BRAZIL-ARCHIVES RIDING THE RAILS REVIEWS BIOGRAPHY

BRAZIL — The Illustrated Guide to the Novel

Part Two

Slave Market at Rio de Janeiro

A free online guide with a wealth of photos and illustrations giving a unique insight into the novel and its creativity.

I searched for the story of Brazil for five years, a literary pathfinder in quest of the epic of the Brazilian people. In this guide, I share my private journal kept on a mighty trek of twenty thousand kilometers across the length and breadth of a vast country.

Discover the magic that goes into the making of a monumental novel with a first draft of three-quarters of million words written in the old-fashioned way, by hand! A quest driven by a passion for writing and storytelling.

Links to the Illustrated Guide to Brazil can be found at the end of each Book Section enhancing the reader's enjoyment of a spellbinding saga "with the look and feel of an enchanted virgin forest, a totally new and original world for the reader-explorer to discover."

Errol Lincoln Uys

Boston, 2010

IMAGE CREDITS APPEAR AT END OF GUIDE

Captions from the text of BRAZIL ©2008 Errol Lincoln Uys

![Rugendas, J.M., Brazil sslave coffle, interior traffic after trade abolition [1]](../images/Rugendas2-Entreposto.jpg) The

stranger was a Portuguese from São Paulo. He had come to the fazenda

leading a great caravan through the caatinga.

The

stranger was a Portuguese from São Paulo. He had come to the fazenda

leading a great caravan through the caatinga.

"Escravos," Chico Tico-Tico explained.

Antônio Paciência knew they were slaves. "Where are they taking them?"

"South to the lands of coffee."

![Brazilian proprietor, Debret [2]](../images/o_regresso_de_um_proprietario_imagelarge.jpg) Fazendeiros

like Heitor Ferreira were the great men of the earth, the rich. Modesto had

yet to see one of the ricos who was not a branco, a white,

or a branco da terra, a white of the earth — a senhor of color

with sufficient prestige or wealth to be accepted as white.

Fazendeiros

like Heitor Ferreira were the great men of the earth, the rich. Modesto had

yet to see one of the ricos who was not a branco, a white,

or a branco da terra, a white of the earth — a senhor of color

with sufficient prestige or wealth to be accepted as white.

![Receipt for sale of slave, Brazil 1851 [3]](../images/Recibo_Compra_venda_escravos.jpg) The

slaver bought Antônio Paciência for three hundred milreis, the equivalent

at the time of 150 dollars, a good price for a slave boy in the northeast sertão,

though the Portuguese expected to receive double this amount when he sold the

boy at São Paulo. The slaver was Saturnino Rabelo, a man in his mid-fifties.

Previously engaged in the African slave trade, for the past four years Rabelo

had been engaged in a lucrative traffic of slaves from north to south Brazil.

The

slaver bought Antônio Paciência for three hundred milreis, the equivalent

at the time of 150 dollars, a good price for a slave boy in the northeast sertão,

though the Portuguese expected to receive double this amount when he sold the

boy at São Paulo. The slaver was Saturnino Rabelo, a man in his mid-fifties.

Previously engaged in the African slave trade, for the past four years Rabelo

had been engaged in a lucrative traffic of slaves from north to south Brazil.

![Portuguese royal family leaves Rio de Janeiro, Debret [4]](../images/partida_da_rainha_para_portugal_imagelarge.jpg) Dom

João saw hope of preserving intact the Bragança's American estate.

"Should Brazil decide to separate from Portugal," he told Crown Prince

Pedro," let it be under your leadership, my son, not that of an adventurer."

Dom

João saw hope of preserving intact the Bragança's American estate.

"Should Brazil decide to separate from Portugal," he told Crown Prince

Pedro," let it be under your leadership, my son, not that of an adventurer."

![Dom Pedro I of Brazil [5]](../images/dompedro1.jpg) Short

and stocky, with a handsome face dominated by large brown eyes, Dom Pedro had

thrived in his exotic place of exile. Generous and friendly, Pedro was also

impulsive, emotional, and had shown a passion for lovemaking. Week after week,

he would hasten from São Cristovão palace in search of new lovers

from all classes and races.

Short

and stocky, with a handsome face dominated by large brown eyes, Dom Pedro had

thrived in his exotic place of exile. Generous and friendly, Pedro was also

impulsive, emotional, and had shown a passion for lovemaking. Week after week,

he would hasten from São Cristovão palace in search of new lovers

from all classes and races.

![Princess Leopoldina arrives at Rio de Janeiro, Debret [6]](../images/DisembarcationofPrincessLeopoldina.jpg) In

1817, the plain flaxen-haired Archduchess Maria Leopoldina sailed for Brazil,

where she married Dom Pedro. Pedro had been awed by his wife's superior intellect,

particularly her abiding interest in botany and mineralogy. But neither marriage

nor the birth of their first child distracted Pedro from his paramours.

In

1817, the plain flaxen-haired Archduchess Maria Leopoldina sailed for Brazil,

where she married Dom Pedro. Pedro had been awed by his wife's superior intellect,

particularly her abiding interest in botany and mineralogy. But neither marriage

nor the birth of their first child distracted Pedro from his paramours.

![Cry of Ypiranga, the declaration of Brazilian independence [7]](../images/433px-Independencia_RMoreaux.jpg) On

September 7, 1822, messengers from Rio de Janeiro overtook Dom Pedro's party

at a small stream called Ipiranga. They were carrying dispatches from Minister

José Bonifácio and a letter from Pedro's wife, Leopoldina: "Pedro,

this is the most important moment of your life. Today, Brazil, which under your

guidance will be a great country, wants you as her monarch."

On

September 7, 1822, messengers from Rio de Janeiro overtook Dom Pedro's party

at a small stream called Ipiranga. They were carrying dispatches from Minister

José Bonifácio and a letter from Pedro's wife, Leopoldina: "Pedro,

this is the most important moment of your life. Today, Brazil, which under your

guidance will be a great country, wants you as her monarch."

Dom Pedro made his decision. "The Cortes is persecuting me. I am an adolescent, they say. I am a Brazilian! Now let them see their adolescent... I proclaim Brazil forever separated from Portugal. From this day hence, our motto is: Independence or Death!"

![Amelie of Leuchtenberg, Empress of Brazil [8]](../images/424px-Amelia_Leuchtenberg.jpg) After

the death of Leopoldina, Dom Pedro's emissaries succeeded in gaining for him

the hand of an enchanting Bavarian princess, Amélie of Leuchtenberg,

granddaughter of Napoleon and Josephine Beauharnais.

After

the death of Leopoldina, Dom Pedro's emissaries succeeded in gaining for him

the hand of an enchanting Bavarian princess, Amélie of Leuchtenberg,

granddaughter of Napoleon and Josephine Beauharnais.

Dom Pedro celebrated the arrival of his seventeen-year-old bride by creating the Order of the Rose in her honor: Love and Fidelity was its motto.

![Dom Pedro II of Brazil [4]](../images/DomPedroIIyoung.jpg) Antônio

Paciência had heard others talk respectfully of this Dom Pedro Segundo,

a poderoso do sertão with power over not merely one fazenda but all Brazil.

Antônio

Paciência had heard others talk respectfully of this Dom Pedro Segundo,

a poderoso do sertão with power over not merely one fazenda but all Brazil.

"Is this his fazenda?" he asked at a big ranch where Saturnino Rabelo had sought further purchases.

"No Pedro Segundo has a grander house at Rio de Janeiro. Ask Policarpo to tell you about it."

Policarpo told Antonio that he had seen not only the palace but Dom Pedro Segundo himself, riding along the Rua Direita in an open carriage with eight cream colored horses plumed with gold feathers.

"'Long live Dom Pedro Segundo! Long live our emperor of Brazil!' I shouted," said Policarpo, his face radiant.

At

the Corte, Dom Pedro and his American aristocrats lived with a semblance of

European elegance, scrupulously observing court etiquette, worshipping foreign

ideas, and devotedly following the latest French fashions.

At

the Corte, Dom Pedro and his American aristocrats lived with a semblance of

European elegance, scrupulously observing court etiquette, worshipping foreign

ideas, and devotedly following the latest French fashions.

![Pedro Segundo's study, Petropolis [11]](../images/pedro2study.jpg) Dom

Pedro wore his crown reluctantly, yearning for the retreat of a contemplative

and scholarly life and dreading the storms of statesmanship.

Dom

Pedro wore his crown reluctantly, yearning for the retreat of a contemplative

and scholarly life and dreading the storms of statesmanship.

"Were I not emperor, I should like to be a teacher,' He said on occasion. "What calling is greater or nobler than directing young minds?"

![View of Rio de Janeiro, 1867 [12]](../images/Rio.jpg) At

the small bay of Botafago, with the Sugar Loaf to one side, between thick groves

of large-leafed banana trees and stately palms, stood the sparkling white mansions

of viscounts, barons, generals. Tropical plants flourished, dense and deeply

green, gaudy blossoms of scarlet lilac and blue mixed with the rose and other

English imports.

At

the small bay of Botafago, with the Sugar Loaf to one side, between thick groves

of large-leafed banana trees and stately palms, stood the sparkling white mansions

of viscounts, barons, generals. Tropical plants flourished, dense and deeply

green, gaudy blossoms of scarlet lilac and blue mixed with the rose and other

English imports.

![Collar of Iron, slave punishment, Brazil, Debret [13]](../images/slavesdebret.jpg) Half

the city's population were black and mulatto slaves: The narrow streets teemed

with half-naked men fulfilling the age-old promise that homens bons be spared

the curse of manual toil in Brazil.

Half

the city's population were black and mulatto slaves: The narrow streets teemed

with half-naked men fulfilling the age-old promise that homens bons be spared

the curse of manual toil in Brazil.

![Mozambican Slaves, Brazil, Rugendas [14]](../images/MozambqiueSlaves.jpg) "What

is your name?"

"What

is your name?"

"Policarpo, senhor."

"Where do you come from?"

"Mozambique, master."

Saturnino Rabelo interjected: "In my fields, Your Honor — a strong and uncomplaining worker." There was a belief that blacks from Mozambique and Angola were natural enemies of labor, as opposed to those from the Gold Coast, who had a reputation for diligence.

![Fazenda Paraiso {15]](../images/Fazenda_do_Paraizo.jpg) Off

to the right, amid

Off

to the right, amid

tufted royal palms and luxuriant bushes and flowers, stood the mansion occupied by the baron of Itatinga and his family.

![A Brazilian lady, 19th century, Debret [17]](../images/uma_senhora_brasileira_em_seu_lar_imagelarge.jpg) She

was tempestuous, with the fire seldom absent from her small black eyes and with

a sharp tongue, but she was a lively, enchanting creature, especially when others

gave her their undivided attention. This she had no difficulty at all commanding,

for Teodora Rita Mendes da Silva was the wife of Ulisses Tavares, baron of Itatinga.

She

was tempestuous, with the fire seldom absent from her small black eyes and with

a sharp tongue, but she was a lively, enchanting creature, especially when others

gave her their undivided attention. This she had no difficulty at all commanding,

for Teodora Rita Mendes da Silva was the wife of Ulisses Tavares, baron of Itatinga.

![Paraguay River, beyond Asuncion [18]](../images/800px-Rio_Paraguay.jpg) On

September 12, 1864, after the midday meal, life aboard the packet Marqués

de Olinda came to a standstill. The privileged among the passengers and

crew retired to bunks and hammocks and wicker chairs; others sought a shaded

patch of deck as the Marqués de Olinda steamed up the Rio Paraguay

at a steady six knots.

On

September 12, 1864, after the midday meal, life aboard the packet Marqués

de Olinda came to a standstill. The privileged among the passengers and

crew retired to bunks and hammocks and wicker chairs; others sought a shaded

patch of deck as the Marqués de Olinda steamed up the Rio Paraguay

at a steady six knots.

![Paraguay, 19th century [18]](../images/paraguaywarmap.jpg) Two

days earlier, the Marqués de Olinda had dropped anchor at Asunción

to take on coal. In this dry season, the capital of Paraguay lay thick with

red dust that swirled up against one-storied houses, mud huts and lean-tos.

Two

days earlier, the Marqués de Olinda had dropped anchor at Asunción

to take on coal. In this dry season, the capital of Paraguay lay thick with

red dust that swirled up against one-storied houses, mud huts and lean-tos.

![Port of Asuncion, 19th century [19]](../images/PortofAsuncion_000.jpg) Construction

gangs were busy at work throughout the city. Presidential palace, opera house,

cathedral; shipyard, arsenal, iron foundry, telegraph office, railway —

after centuries of colonial slumber, Paraguay was in the midst of an industrial

revolution, attracting hundreds of skilled European engineers and craftsmen.

Construction

gangs were busy at work throughout the city. Presidential palace, opera house,

cathedral; shipyard, arsenal, iron foundry, telegraph office, railway —

after centuries of colonial slumber, Paraguay was in the midst of an industrial

revolution, attracting hundreds of skilled European engineers and craftsmen.

![President Francisco Solano Lopez of Paraguay [20]](../images/Solano1.jpg) "Perhaps

Solano López has a purpose in building his war machine," Telles

Brandão said.

"Perhaps

Solano López has a purpose in building his war machine," Telles

Brandão said.

Mendonça looked up expectantly. Coronel Frederico's eyes were half open.

"Emperor López, the Napoleon of the Plata!"

"And a crown for his Irish princess?" Mendonça said, a glint in his beady eyes.

Telles Brandão smiled at this reference to eliza Alicia Lynch, mistress of Solano López. "You jest, Sabino. There's talk at Buenos Aires that López has crown and scepter on order from Europe."

![Eliza Alicia Lynch, Paraguay [21]](../images/ElizaLynch_000.jpg) "What

a beauty!" said Telles Brandão. "Her skin is alabaster; her

eyes are blue-green. La Lynch is tall, with a seductive figure. When she crosses

a room, from her crown of reddish hair to her small feet —.a goddess!"

"What

a beauty!" said Telles Brandão. "Her skin is alabaster; her

eyes are blue-green. La Lynch is tall, with a seductive figure. When she crosses

a room, from her crown of reddish hair to her small feet —.a goddess!"

Eliza Lynch was nine when her father fled Ireland for France in the great famine of 1845. At fifteen, she was given to Quatrefages, a French officer, who took her to Algiers. Some say she left him for a Russian noble; some, that Quatrefages deserted her. When López met her in Paris, she was nineteen and rid of Quatrefages. La Lynch has given López five sons; but the word is he'll never marry her, not while he's so eager to infuse his line with royal blood."

![Tacuari, flagship Parguayan Navy 1865 [22]](../images/Tacuari.jpg) The

Tacuari ran up signal flags ordering them to stop immediately. The

Marqués de Olinda ignored the command. And then, without warning,

there was a roar and a flash, and the cannon on her poop deck threw a shell

across the bows of the Marqués de Olinda.

The

Tacuari ran up signal flags ordering them to stop immediately. The

Marqués de Olinda ignored the command. And then, without warning,

there was a roar and a flash, and the cannon on her poop deck threw a shell

across the bows of the Marqués de Olinda.

![Waltz 1860s [23]](../images/waltzing.jpg) M.

Armand trembled with excitement as he reached for some papers on the Broadwood.

"Humbly, Baron, for your kindness, your welcome, I give you both —

Teodora Rita's Waltz!"

M.

Armand trembled with excitement as he reached for some papers on the Broadwood.

"Humbly, Baron, for your kindness, your welcome, I give you both —

Teodora Rita's Waltz!"

It was as lovely and romantic a valse as the brilliant melodies from mirth-loving Vienna, danced for the first time this night, so far, far away from the thunder gathering at the Plata.

![Amazonas, Paraguayan War [24]](../images/AmazonasFrigate_000.jpg) Early

morning on June 11, 1865, nine Brazilian warships were anchored ten miles below

Tres Bocas, with the Riachuelo, a stream flowing into it from the east. The

flagship was the Amazonas, a 195-foot, 370-ton wooden frigate, the

only paddle wheeler among the nine ships.

Early

morning on June 11, 1865, nine Brazilian warships were anchored ten miles below

Tres Bocas, with the Riachuelo, a stream flowing into it from the east. The

flagship was the Amazonas, a 195-foot, 370-ton wooden frigate, the

only paddle wheeler among the nine ships.

![Vice-Admiral Francisco Manoel Barroso, Brazilian Navy [24]](../images/BarrosoBrazilianNavyArchives_000.jpg) To

get a better view of the enemy, Admiral Barroso had climbed up onto one of the

Amazonas's paddle boxes. "make this signal to the squadron."

To

get a better view of the enemy, Admiral Barroso had climbed up onto one of the

Amazonas's paddle boxes. "make this signal to the squadron."

Barroso glanced swiftly along the line of his ships. Then he addressed the midshipman with orders for signal flags to be flown with two commands:

The first was for the ships to engage the enemy at close quarters. The second was inspired by the glory of Trafalgar sixty years ago: "O Brasil espera que cada um compra o seu dever!" — "Brazil expects that every man will do his duty!"

![Battle of Riachuelo, Paraguayan War [25]](../images/800px-Batalha_riachuelo_victor_meirelles.jpg) Full

steam ahead, her great paddle wheel churning the water, the Amazonas

came down before the three-knot current. On and on she rode, belching black

smoke from her stack and red flame from the mouths of her cannon, steaming directly

for the Paraguarí, the newest vessel in President López's

fleet.

Full

steam ahead, her great paddle wheel churning the water, the Amazonas

came down before the three-knot current. On and on she rode, belching black

smoke from her stack and red flame from the mouths of her cannon, steaming directly

for the Paraguarí, the newest vessel in President López's

fleet.

She struck the Paraguarí amidships, her ram buckling iron plates, smashing through the enemy's bulwarks.

![Slaves on coffee fazenda, Frond, courtesy MultiRio [26]](../images/Frond-coffee_slaves2.jpg) In

truth, Policarpo was lazy, and had resented the regimen of the plantation, particularly

at harvest time, when the slave bell rang at 5:00 a.m. for assembly and prayers

in front of the mansion before work in the coffee groves until dusk.

In

truth, Policarpo was lazy, and had resented the regimen of the plantation, particularly

at harvest time, when the slave bell rang at 5:00 a.m. for assembly and prayers

in front of the mansion before work in the coffee groves until dusk.

![Slave quarters, Viktor Frond, courtesy MultiRio [27]](../images/senzala.jpg) The

move to the senzala had been almost as traumatic as being sold away from Mãe

Mônica. Cast among the mass of Itatinga's 220 slaves, Antônio had

experienced deprivation that went far beyond being stripped of the nice clothes

he had worn on parade in front of Teodora Rita's guests or denied the food from

the fazenda's kitchen.

The

move to the senzala had been almost as traumatic as being sold away from Mãe

Mônica. Cast among the mass of Itatinga's 220 slaves, Antônio had

experienced deprivation that went far beyond being stripped of the nice clothes

he had worn on parade in front of Teodora Rita's guests or denied the food from

the fazenda's kitchen.

![Voluntarios da Patria, Brazil [28]](../images/VontariosdaPatria.jpg) When

the ninety-two voluntários of Tiberica left the town square, the baron's

grandson had ridden at the head of them.

When

the ninety-two voluntários of Tiberica left the town square, the baron's

grandson had ridden at the head of them.

Included in the column, marching three abreast, had been twenty-seven slaves from fazendas in the district. Some had tramped along with bewildered looks, for they feared this service for which their masters had volunteered them.

Antônio Paciência marched beside Policarpo Mosssambe, the pair among six chosen from Itatinga as voluntários da Patria.

![Paraguayan Infantry, War of the Triple Alliance [29]](../images/paraguaioinfantry.jpg) "Macacos...macacos...macacos."

"Macacos...macacos...macacos."

General Juan Bautista Noguera intoned the epithet with a deadly calm as he watched the river armada draw near the low-lying banks where the Rio Paraguay fell into the Paraná.

Four thousand soldiers were in position along the banks of the Upper Paraná, an invasion by the Allies accepted as inevitable for months.

![Itapiru, Candido Lopez [29]](../images/ItapiruApril1866_000.jpg) "Macacos...macacos...macacos."

"Macacos...macacos...macacos."

War steamers, transports, flat barges, and canoes as far as they eye could see. And to challenge them, Cacambo with two hundred men and boys, most of them carrying flintlock muskets and machetes.

![Battle of Tuyuti, Candido Lopez [30]](../images/Tuyuti2wiki.jpg) Sweeping

down on the right toward the Argentinian flank, thundering out of the cover

of a palm forest, came seven thousand cavalrymen with two thousand foot soldiers

running up behind them. Pouring directly from the estero in a frontal assault

on the Bateria Mallet were five thousand infantrymen, with four howitzers. Altogether

some 23,000 men, the bulk of Paraguay's army.

Sweeping

down on the right toward the Argentinian flank, thundering out of the cover

of a palm forest, came seven thousand cavalrymen with two thousand foot soldiers

running up behind them. Pouring directly from the estero in a frontal assault

on the Bateria Mallet were five thousand infantrymen, with four howitzers. Altogether

some 23,000 men, the bulk of Paraguay's army.

By noon of May 24, 1866, five minutes after the Paraguayans' rocket signal to commence the attack, the battle of Tuyuti was raging along the whole line of the allies.

![Battle of Tuyuti, War of Triple Alliance [31]](../images/Tuyutiuruguayans.jpg) "Ai,

Jesus Christ! How Terrible!" António cried. "Some are so small

and thin, there's nothing to burn."

"Ai,

Jesus Christ! How Terrible!" António cried. "Some are so small

and thin, there's nothing to burn."

The Paraguayan dead were being heaped up in alternate layers. Of 23,000 men sent into battle, six thousand were dead and seven thousand injured. The Allied losses were four thousand.

![Civil War torpedoes [32]](../images/rebel-confederate-torpedo.jpg) Luke's

torpedoes varied in size from 50-pounders to a monster boiler-plated 1,500-pounder,

the stationary weapons were anchored so that they drifted four to five feet

below the surface; those sent downstream floated attached to barrels or demijohns.

Luke's

torpedoes varied in size from 50-pounders to a monster boiler-plated 1,500-pounder,

the stationary weapons were anchored so that they drifted four to five feet

below the surface; those sent downstream floated attached to barrels or demijohns.

![Battle of Curupaiti, September 1866, Candido Lopez [33]](../images/Curupatiwiki.jpg) Policarpo

had worked his way about six feet into the abatis.

Policarpo

had worked his way about six feet into the abatis.

"Policarpo!" Antônio shouted. "Come down! We'll burn it!"

Policarpo had his back to Antônio; he raised the ax for one last swing.

An instant later, the shell exploded at the front edge of the tangle of trees, hurling Policarpo Mossambe high into the air.

![Cerro Leon Hospital, Paraguay [33]](../images/cerroleonhospitalThompson_000.jpg) Several

hundred mothers and daughters served in a Paraguayan women's corps, working

in the hospitals, cleaning the barracks and campgrounds, and cultivating fields.

The women sent deputations to the marshal president asking to be drilled as

soldiers and allowed to fight, but López had turned down these requests.

Several

hundred mothers and daughters served in a Paraguayan women's corps, working

in the hospitals, cleaning the barracks and campgrounds, and cultivating fields.

The women sent deputations to the marshal president asking to be drilled as

soldiers and allowed to fight, but López had turned down these requests.

![Ana Neri, the Florence Nightingale of Brazil [35]](../images/Ana_Neri.jpg)

Dona Ana Néri had been fifty-one, living comfortably at her home outside Salvador, Bahia, when she badgered the military authorities to let her sail for the Plata. She'd become a legend, not only for her compassion toward both friend and foe, but also for fearlessness in passing through the very fire of battle to aid the wounded, a mission that had brought her the deepest sorrow a mother can know:

Following a skirmish near the esteros, Dona Ana had found one of her own sons dead at the edge of the morass.

![Bateria Londres, Humaita [35]](../images/BateriaLondres_000.jpg) At

Humaitá, men and boys waited at eighty-four cannon at the Bateria de

Londres and other gun emplacements. Some were battle-hardened veterans. Some

child gunners waited gallantly beside cannon the muzzles of which they could

reach only on tiptoe.

At

Humaitá, men and boys waited at eighty-four cannon at the Bateria de

Londres and other gun emplacements. Some were battle-hardened veterans. Some

child gunners waited gallantly beside cannon the muzzles of which they could

reach only on tiptoe.

![Passage of Humaita, Brazilian monitors, Candido Lopez [36]](../images/PassageofHumaita_000.jpg) "Cease

fire!" Tuttle looked up to see the battery commander standing there.

"Cease

fire!" Tuttle looked up to see the battery commander standing there.

"Cease fire?" Tuttle asked incredulously.

"Stop shooting at the monitor. Watch closely, Major. There are one hundred and fifty men out there. They'll storm her decks and take her prize."

![Bombardment of Humaita Cathedral, War of Triple Alliance, Paraguay [37]](../images/humaitachurch_000.jpg) Through

the winter of 1868, a cold miserable four months, the Allies laid siege to Humaitá.

The three thousand defenders deceived the Allies into believing their strength

to be much greater with rows of Quaker guns — leather-bound tree trunks

— and a frequent clangor of brass and drums.

Through

the winter of 1868, a cold miserable four months, the Allies laid siege to Humaitá.

The three thousand defenders deceived the Allies into believing their strength

to be much greater with rows of Quaker guns — leather-bound tree trunks

— and a frequent clangor of brass and drums.

![War of the Triple Alliance, Paraguay, battlefield dead [38]](../images/ParaguayanWarDead_000.gif) Antônio

Paciência and Urubu were still out searching for wounded, wandering across

this landscape of horrors at Avaí. Arms, legs, heads, torsos had been

scattered by shell blasts; hundreds of men were strewn haphazardly in unnatural

positions, their bodies broken and contorted; as many horses littered the area,

huge, stiff, with flies swarming upon their warm carcasses.

Antônio

Paciência and Urubu were still out searching for wounded, wandering across

this landscape of horrors at Avaí. Arms, legs, heads, torsos had been

scattered by shell blasts; hundreds of men were strewn haphazardly in unnatural

positions, their bodies broken and contorted; as many horses littered the area,

huge, stiff, with flies swarming upon their warm carcasses.

![Asuncion Cathedral [39]](../images/Asuncion_Cathedral.jpg) From,

the spires of Asunción's cathedral on the third Sunday of January 1869,

the peal of bells rang out over the capital as the marquês de Caxias and

his commanders gathered to thank God for victory.

From,

the spires of Asunción's cathedral on the third Sunday of January 1869,

the peal of bells rang out over the capital as the marquês de Caxias and

his commanders gathered to thank God for victory.

As the marquês and his officers raised their voices to heaven, outside the cathedral the scene was closer to hell.

The rape of the Mother of Cities began slowly...

![Dom Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil [41]](../images/475px-Pedro_II_of_Brazil_-_Brady-Handy.jpg) Most

officers were sick and tired of the war and began to talk of the need to offer

López terms for an honorable surrender.

Most

officers were sick and tired of the war and began to talk of the need to offer

López terms for an honorable surrender.

A thousand miles away His Imperial Majesty Dom Pedro thought differently. What was needed was a young commander capable of reinvigorating the imperial army and leading the hunt for López — a bandit upon whose head His Majesty now placed a reward.

![1860s locomotive, Paraguay [41]](../images/trenSapucai_000.jpg)

The raiders did not travel quietly. They burst into Pirayu from their base camp to the south in a locomotive hurtling past the dark slopes of Mbatovi Mountain, with two tattered red, white and blue banners of the Republic of Paraguay streaming to each side of the engine's smokebox, its chimney spewing a fiery rain of hot ash and cinders.

![Child soldiers, Paraguay, War of the Triple Alliance [42]](../images/BoySoldiers.jpg) There

was a wood just south of the plain at Acosta Ñu. In the fading light

tiny black dots could be seen emerging from out of the trees, scuttling through

the macega toward the Paraguayan lines; they looked like so many squads of small,

dark peccaries bolting through the grass. And like wild pigs, they provided

excellent sport for cavalrymen who rode them down, sticking them with their

lances.

There

was a wood just south of the plain at Acosta Ñu. In the fading light

tiny black dots could be seen emerging from out of the trees, scuttling through

the macega toward the Paraguayan lines; they looked like so many squads of small,

dark peccaries bolting through the grass. And like wild pigs, they provided

excellent sport for cavalrymen who rode them down, sticking them with their

lances.

Those tiny figures dashing across the macega were the mothers of boys in the trenches. They had hidden in the woods all day watching the progress of battle and were running to see if their children were dead or alive.

![La Paraguaya, Juan Manuel Banes, [42]](../images/la-paraguaya.jpg) Francisco

Solano López then spoke his last words: "¡Muero con mi patria!"

("I die with my country!")

Francisco

Solano López then spoke his last words: "¡Muero con mi patria!"

("I die with my country!")

There was never a truer epitaph.

In five years of war, ninety percent of the men and boys of Paraguay were slain.

Paraguay, the land of the Guarani, was dead.

![Teatro Santa Isabel, recife [1]](../images/TeatroSantaIsabel-Recife.jpg) At

Recife on a Sunday afternoon in November 1884, a crowd filled the Teatro Santa

Isabel and overflowed onto the Campo das Princesas in the city center. Those

unable to get into the building surged toward its open windows hoping to catch

a glimpse of Joaquim Aurélio Nabuco, lawyer and journalist, the man of

the hour in Brazil.

At

Recife on a Sunday afternoon in November 1884, a crowd filled the Teatro Santa

Isabel and overflowed onto the Campo das Princesas in the city center. Those

unable to get into the building surged toward its open windows hoping to catch

a glimpse of Joaquim Aurélio Nabuco, lawyer and journalist, the man of

the hour in Brazil.

![Joaquim Nabuco, Brazilian abolitionist, politician and writer [2]](../images/Nabuco.jpg) "Handsome

Jack," his friends called him. He was over six feet tall. His dark, wavy

hair was parted in the center, his moustache luxurious.

"Handsome

Jack," his friends called him. He was over six feet tall. His dark, wavy

hair was parted in the center, his moustache luxurious.

"Our opponents tell the world that because the womb of the slave is free, slavery is extinct in Brazil. That law is a sham. Consider the female slave born on September,ber 27, 1971, the day before the law came into effect. Her mother's womb was not free so she remains a slave, who at the age of forty, 1911, may bear a child. If this ingênuo's ("innocent's") owner refuses the indemnity, the ingênuo can be kept in provisional slavery until the age of 21 — 1932. Seventy years after Lincoln's proclamation, Brazil will have a generation languishing in the senzalas.

![Casa Grande, Pernambuco sugar plantation [5]](../images/CasaGrandeMorenoJNF.jpg) The

Casa Grande dominated the landscape like a bulwark against change. Five generations

of Cavalcantis had controlled the plantation from this grand old mansion.

The

Casa Grande dominated the landscape like a bulwark against change. Five generations

of Cavalcantis had controlled the plantation from this grand old mansion.

![Pumati engenho, Pernambuco, view from the Casa Grande [4]](../images/Engenho3.jpg) "I

could love no place as much as the valley of my family," Fábio told

Joaquim Nabuco. "For generations, the Cavalcantis of Santo Tomás

have been on these lands. The great estate of our forefathers has been subdivided

by inheritance, but even now, twenty thousand acres belong to the engenho, three-quarters

of which have never been cultivated. For us, a blessing, for the future; for

Brazil, a curse?"

"I

could love no place as much as the valley of my family," Fábio told

Joaquim Nabuco. "For generations, the Cavalcantis of Santo Tomás

have been on these lands. The great estate of our forefathers has been subdivided

by inheritance, but even now, twenty thousand acres belong to the engenho, three-quarters

of which have never been cultivated. For us, a blessing, for the future; for

Brazil, a curse?"

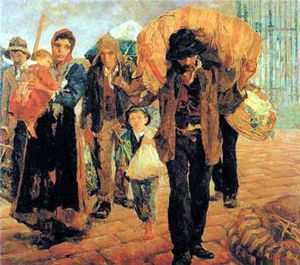

![Drought ravaged land [5]](../images/CearaDrought.jpg) For

eight months, Dr. Fábio Cavalcanti worked with other doctors at Fortaleza,

Ceará, among the tens of thousands who fled the drought in the interior.

The refugee camps were a hecatomb; 15,390 souls were carried out to trenches

during one month alone. The seca was a calamity of nature, but the

improvidence, filth, and abject poverty of the stricken people streaming to

the coast — Fabio saw this as the work of man.

For

eight months, Dr. Fábio Cavalcanti worked with other doctors at Fortaleza,

Ceará, among the tens of thousands who fled the drought in the interior.

The refugee camps were a hecatomb; 15,390 souls were carried out to trenches

during one month alone. The seca was a calamity of nature, but the

improvidence, filth, and abject poverty of the stricken people streaming to

the coast — Fabio saw this as the work of man.

![Plantation, interior Brazil [6]](../images/PlantationBraziloldprint.jpg) The

most inviting aspect of Rosário was the luxuriance of its setting. Tamarind,

manguiero, cashew, wild bananas flourished beside cultivated groves of coffee,

orange, lemon. Ancient forest giants bearded with moss toward above gardens

with roses, carnations, lavender.

The

most inviting aspect of Rosário was the luxuriance of its setting. Tamarind,

manguiero, cashew, wild bananas flourished beside cultivated groves of coffee,

orange, lemon. Ancient forest giants bearded with moss toward above gardens

with roses, carnations, lavender.

![Resisting Emacipation, Brazil 1880. Angelo Agostino [7]](../images/Emancipa.jpg) Henrique

put his hand on Celso's shoulder" "I know it's difficult for you,

Celso, a Cavalcanti of Santo Tomás, but think of the day this rotten

institution ceases to exist in Brazil — the hour when men like your father

are free, too. The chains of slavery bind them no less than those they hold

in bondage."

Henrique

put his hand on Celso's shoulder" "I know it's difficult for you,

Celso, a Cavalcanti of Santo Tomás, but think of the day this rotten

institution ceases to exist in Brazil — the hour when men like your father

are free, too. The chains of slavery bind them no less than those they hold

in bondage."

![Itamaraca Island, Pernambuco [8]](../images/ilha-itamaraca.jpg) On

the fourth night, confident of success now, Celso and Slipper George led the

final dash to Itamaracá Island. At 3:00 A.M., they stood with all fifty

slaves on the broad bank of a river separating the island from the mainland.

The slaves were ferried to Itamaracá ten at a time on a jangada that

had been left at this crossing point by members of the Termite Club.

On

the fourth night, confident of success now, Celso and Slipper George led the

final dash to Itamaracá Island. At 3:00 A.M., they stood with all fifty

slaves on the broad bank of a river separating the island from the mainland.

The slaves were ferried to Itamaracá ten at a time on a jangada that

had been left at this crossing point by members of the Termite Club.

"Oh, my boy, what a lovely thing you've done!"

"We brought fifty slaves, Agamemnon!"

"No, Celso — "

"Yes, Agamemnon. Fifty!"

"Not slaves, Celso. They are free!"

![usina, sugar mill [9]](../images/usina.jpg) On

September 11, 1886, the day for the inauguration of Usina Jacuribe, the procession

entered the cavernous iron building and moved beside a long feeder tray to the

massive Fives-Lille mill.

On

September 11, 1886, the day for the inauguration of Usina Jacuribe, the procession

entered the cavernous iron building and moved beside a long feeder tray to the

massive Fives-Lille mill.

Padre José asked the Lord's blessing on this great piece of machinery and sprinkled holy water in its direction.

![Fives-Lille engine [9]](../images/FivesLille.jpg) "In this golden moment, I raise my eyes to a new horizon," said Rodrigo

Cavalcanti, Baron of Jacuribe."The engenhos have struggled against competition

from many quarters—from the sugar-beet producers of Europe to the cane

growers of the West Indies. The usina will be our salvation."

"In this golden moment, I raise my eyes to a new horizon," said Rodrigo

Cavalcanti, Baron of Jacuribe."The engenhos have struggled against competition

from many quarters—from the sugar-beet producers of Europe to the cane

growers of the West Indies. The usina will be our salvation."

![Engenho Chapel, Pumati, Pernambuco [10]](../images/Engenho6.jpg) Many

years since the engenho had a resident priest, the small sanctuary was well

maintained; its woodwork varnished, the walls immaculately white, and the altar

gilded.

Many

years since the engenho had a resident priest, the small sanctuary was well

maintained; its woodwork varnished, the walls immaculately white, and the altar

gilded.

"Celso."

It seemed as if Celso had known all along his father was there.

"I came to give thanks to our Lord, Senhor Pai."

![Coffee Fazenda, drying terrace [12]](../images/PatioFazendadecafe.jpg) In

the first half of 1887, reports of desertions and mass rumors of mass runaways

reached Sáo Paulo. The coffee harvest had been underway since April,

and the Paulista planters were confident that this season's berries would reach

their drying terraces.

In

the first half of 1887, reports of desertions and mass rumors of mass runaways

reached Sáo Paulo. The coffee harvest had been underway since April,

and the Paulista planters were confident that this season's berries would reach

their drying terraces.

As

Firmino Dantas and Aristedes strolled across the praça at Tiberica, they

spoke of Italian immigration.

As

Firmino Dantas and Aristedes strolled across the praça at Tiberica, they

spoke of Italian immigration.

"There's no hope in Italy for the peasants," Aristedes said."When I toured the country, I saw the depth of poverty. God only knows, but the families who land at Santos can hope for a life better than they've every known."

![Ama de leite. Casa-Grande e Senzala em Quadrinhos [14]](../images/Maidandchild.jpg) Babá

Epifánia, a big, square-faced woman in her early fifties, had come to

Brazil from the lands of the BaKongo in 1847, transported illegally after the

abolition of the slave trade. Bought by Ulisses Tavares, Epifánia had

served as wet nurse at Itatinga, suckling numerous da Silva infants, Aristedes

and his sister, Carmen, among them. When the baron died, babá Epifánia

had been among ten favorites slaves manumitted according to the term of Ulisses

Taveres's will.

Babá

Epifánia, a big, square-faced woman in her early fifties, had come to

Brazil from the lands of the BaKongo in 1847, transported illegally after the

abolition of the slave trade. Bought by Ulisses Tavares, Epifánia had

served as wet nurse at Itatinga, suckling numerous da Silva infants, Aristedes

and his sister, Carmen, among them. When the baron died, babá Epifánia

had been among ten favorites slaves manumitted according to the term of Ulisses

Taveres's will.

![Confesderate Veterans Memorial, Vila Americana, Brazil [15]](../images/ConfedmemorialinVilaAmericana.jpg) Cadmus

Rawlings had come to Brazil after the Civil War, along with several hundred

families of Confederate exiles now scattered from the banks of the Tapajós

to the coffee lands of São Paulo. Some emigres struggling in ramshackle

dwellings in the Amazon jungle were demoralized but others were making a go

of it in their new homeland, especially a group of farmers at Santa Barbara,

who had achieved success growing a succulent watermelon, the "Georgia Rattlesnake."

Cadmus

Rawlings had come to Brazil after the Civil War, along with several hundred

families of Confederate exiles now scattered from the banks of the Tapajós

to the coffee lands of São Paulo. Some emigres struggling in ramshackle

dwellings in the Amazon jungle were demoralized but others were making a go

of it in their new homeland, especially a group of farmers at Santa Barbara,

who had achieved success growing a succulent watermelon, the "Georgia Rattlesnake."

![Jabaquara Quilombo, Santos, Brazil [16]](../images/jabaquara.jpg) On

October 24, 1887, 4,500 runaways now living in Jabaquará quilombo witnessed

a unique procession. First came a company of thirty drummers, musicians with

the berimbau and xaque-xaque, and a huge cart with the "Queen of Liberty"

— babá Epifánia, reveling in her hour of glory.

On

October 24, 1887, 4,500 runaways now living in Jabaquará quilombo witnessed

a unique procession. First came a company of thirty drummers, musicians with

the berimbau and xaque-xaque, and a huge cart with the "Queen of Liberty"

— babá Epifánia, reveling in her hour of glory.

![Golden Law, May 13, 1888, Brazil, Abolition decress [17]](../images/GoldenLaw.jpg) On

May 13, 1888, ten days after the opening of Parliament by Princess Isabel acting

as regent for Dom Pedro, who was in Europe, an Act abolishing slavery in Brazil

completed its passage through both houses.

On

May 13, 1888, ten days after the opening of Parliament by Princess Isabel acting

as regent for Dom Pedro, who was in Europe, an Act abolishing slavery in Brazil

completed its passage through both houses.

![Ilha Fiscal Ball, Brazil [18]](../images/LastBall.jpg) In

the fair-tale setting on Ilha Fiscal, most nobles and Frock Coats, secure in

the knowledge that the empire had survived previous outbreaks of republicanism

and other manifestations of discontent, were confident that the monarchy would

ride out this storm.

In

the fair-tale setting on Ilha Fiscal, most nobles and Frock Coats, secure in

the knowledge that the empire had survived previous outbreaks of republicanism

and other manifestations of discontent, were confident that the monarchy would

ride out this storm.

![Panorama do Flamengo e de Laranjeiras, 1893/1894 [19]](../images/Flamengo.jpg) Aristedes

and Anna Pinto were staying at Clóvis Lima's house in the suburb of Flamengo.

Colonel Clóvis was still with those loyal to the emperor, but Aristedes

knew were it not for the the hesitancy of older men such as Clóvis and

Marshal Deodora da Fonseca, the army would be in open rebellion.

Aristedes

and Anna Pinto were staying at Clóvis Lima's house in the suburb of Flamengo.

Colonel Clóvis was still with those loyal to the emperor, but Aristedes

knew were it not for the the hesitancy of older men such as Clóvis and

Marshal Deodora da Fonseca, the army would be in open rebellion.

![Brazilian Royal Family 1888, Henschel [20]](../images/800px-Familia_Imperial_1887.jpg) The

packet Alagoas carrying the Braganças to exile in Europe rode

slowly past the island of Fernando do Noronha.

The

packet Alagoas carrying the Braganças to exile in Europe rode

slowly past the island of Fernando do Noronha.

His Majesty stood on the deck, the breeze ruffling his white hair. "Saudade," he said, thinking aloud."Saudades do Brasil."... An expression of profound melancholy.

![Antonio Consolheiro, The Counselor [21]](../images/consolheiro.jpg) Antônio

Conselheiro was from the town of Quixeramobim, in the province of Ceará,

where he was born in 1828 as Antonio Vicente Mendes Maciel. By 1876, he was

known as The Counselor and was attracting a wide following to his "Camp

of the Good Jesus."

Antônio

Conselheiro was from the town of Quixeramobim, in the province of Ceará,

where he was born in 1828 as Antonio Vicente Mendes Maciel. By 1876, he was

known as The Counselor and was attracting a wide following to his "Camp

of the Good Jesus."

For sixteen years, he roamed the sertáo, passing through the caatinga from fazenda to fazenda, vila to vila. Finally, in 1893, The Counselor, sixty-five years old, found a permanent refuge: Canudos.

![Canudos, Brazil [22]](../images/Canudos2.jpg) A

vast, uneven plain rose behind the Vasa-Barris. Near the river stood a massive

unfinished church with two huge towers; to its right in an open area was a dilapidated

chapel. Behind the church were several substantial buildings. Behind these,

in barrios spreading across the Vasa-Barris, five thousand mud-walled homes,

with a labyrinth of streets and alleys.

A

vast, uneven plain rose behind the Vasa-Barris. Near the river stood a massive

unfinished church with two huge towers; to its right in an open area was a dilapidated

chapel. Behind the church were several substantial buildings. Behind these,

in barrios spreading across the Vasa-Barris, five thousand mud-walled homes,

with a labyrinth of streets and alleys.

![Canudos, combatants, outside Church of Bom Jesus [23]](../images/CombatentesCanudosFlaviodeBarros1897.jpg) The

outlaws numbered several hundred, but by late 1896, an estimated twenty thousand

souls were gathered on the plain, the majority of them sertanejos whose most

serious offense had been to turn their backs on the poderosos de sertão.

All had heard the voice of Hope calling them to the New Jerusalem.

The

outlaws numbered several hundred, but by late 1896, an estimated twenty thousand

souls were gathered on the plain, the majority of them sertanejos whose most

serious offense had been to turn their backs on the poderosos de sertão.

All had heard the voice of Hope calling them to the New Jerusalem.

![Canudos, dwelling [24]](../images/canudostypicalhouse.jpg) As

Antônio Paciência entered his house, he heard a small voice: "Papai?"

As

Antônio Paciência entered his house, he heard a small voice: "Papai?"

"Yes, Juraci."

Juraci Cristiano was almost four an a half years old. "I heard the guns, Papai."

He ruffled his son's hair. "You were frightened?"

The child did not answer the question. "Papai killed the macacos?" he asked.

"We saw many fall."

![God's Thunderer, Canudos Rebellion [25]](../images/A_matadeira.jpg) "God's

Thunderer," a Whitworth 32-pounder brought to silence the voice of the

false prophet...Thin-legged and scrawny, Teotônio shot forward at the

heels of the leaders. The jagunço and three other men carried spluttering

grenades, but they threw them too soon, and the missiles exploded in front of

the Whitworth.

"God's

Thunderer," a Whitworth 32-pounder brought to silence the voice of the

false prophet...Thin-legged and scrawny, Teotônio shot forward at the

heels of the leaders. The jagunço and three other men carried spluttering

grenades, but they threw them too soon, and the missiles exploded in front of

the Whitworth.

![Canudos Brazilian Army headquarters, Cel Pedro Paulo Cantalíce Estigarríbia [26]](../images/quadro_canudos.jpg) The

fourth expedition came close to repeating the earlier disasters until the supply

trains began to get through from Monte Santo. During August, three thousand

reinforcements had arrived, coming to replace two thousand men wounded or exhausted

from illness.

The

fourth expedition came close to repeating the earlier disasters until the supply

trains began to get through from Monte Santo. During August, three thousand

reinforcements had arrived, coming to replace two thousand men wounded or exhausted

from illness.

![Ruins of the New Church, Canudos, Flavio Barros [27]](../images/guerra-de-canudos-flavio-de-barros6.jpg) Canudos

came under daily bombardment as the siege lines advanced east and west of the

plain in mid-September. The towers of the new church were leveled to the ground,

the walls blasted apart, the guns moved here smashed. One hundred sixty-seven

rebels died at the church, but others still went willingly to defend the huge

pile of rubble where Antônio Paciência himself had labored to build

the temple of New Jerusalem.

Canudos

came under daily bombardment as the siege lines advanced east and west of the

plain in mid-September. The towers of the new church were leveled to the ground,

the walls blasted apart, the guns moved here smashed. One hundred sixty-seven

rebels died at the church, but others still went willingly to defend the huge

pile of rubble where Antônio Paciência himself had labored to build

the temple of New Jerusalem.

![Euclides da Cunha, author of Rebellion in the Backlands [28]](../images/Euclides_da_Cunha.jpg) "When

I left Salvador, I thought I had a good idea of what to expect," Euclides

da Cunha said. "The farther away from the coast, the more I felt that not

only was I entering a foreign land; I was journeying into the past.

If the sertanejo is pariah owing to his poverty and ignorance, it's because

for three centuries we concerned ourselves with building up out civilization

at the coast, abandoning a third, perhaps more, of our nation in these backlands.

"When

I left Salvador, I thought I had a good idea of what to expect," Euclides

da Cunha said. "The farther away from the coast, the more I felt that not

only was I entering a foreign land; I was journeying into the past.

If the sertanejo is pariah owing to his poverty and ignorance, it's because

for three centuries we concerned ourselves with building up out civilization

at the coast, abandoning a third, perhaps more, of our nation in these backlands.

"These criminals, as the major calls them, are mostly the descendants of the bandeirantes, the bedrock of our race..."

![Wood carving, photo by Leo Reynolds [29]](../images/angel.jpg) Placido

himself did not know exactly how old he was, but he had been born in the time

of King João of Portugal, His failing eyesight did not prevent "Woodcutter,"

as was known to all from working on an immense carving he called "Gabriel,"

an eight-feet high angel.

Placido

himself did not know exactly how old he was, but he had been born in the time

of King João of Portugal, His failing eyesight did not prevent "Woodcutter,"

as was known to all from working on an immense carving he called "Gabriel,"

an eight-feet high angel.

![Women and Children of Canudos, Brazil, surrender [30]](../images/Canudos_rebels.jpg) "They're

sending us their women and children," an officer told Celso Cavalcanti.

"They're

sending us their women and children," an officer told Celso Cavalcanti.

Some children were naked; some women wore only a cloth around their privates, their breasts encrusted with dirt. Some walked silently; some wept; some begged water; some cried aloud that Conselheiro should see them and carry them to Heaven.

![Monte Santo chapel, Bahia , homage [31]](../images/candles.jpg) Three

days later, the government soldiers stormed a trench, killing the last defenders,

among them a mulatto and a venerable caboclo. They died side by side, these

two fanatics who answered the call of Antônio Conselheiro.

Three

days later, the government soldiers stormed a trench, killing the last defenders,

among them a mulatto and a venerable caboclo. They died side by side, these

two fanatics who answered the call of Antônio Conselheiro.

One was Placido de Paulo, Woodcutter, who had come late to the fight in silent anger after he had seen great angel Gabriel go up in flames.

The other was Patent Anthony, who asked little of the great men on the earth and had got nothing: Antônio Paciência — Brasileiro!

![Antonio Conselheiro's remains [32]](../images/Antonio_Conselheiro.jpg) New

Jerusalem was razed. In the interests of science, Antônio Conselheiro's

body was dug up and the head cut off and dispatched to the Bahia, where it was

to be probed for indications of madness.

New

Jerusalem was razed. In the interests of science, Antônio Conselheiro's

body was dug up and the head cut off and dispatched to the Bahia, where it was

to be probed for indications of madness.

![Child of Brazil, Tamaris, Carf Foundation [33]](../images/BrazilianGirl.jpg) "The

races have intermingled here for four centuries. If I stand in the Praça

de Sé at the Bahia, I see around me people of every shade: blacks; whites;

mulattoes; morenos; caboclos. This is the reality of Brazil: a new race is evolving

here in the tropics, not a pale imitation of the Europeans."

"The

races have intermingled here for four centuries. If I stand in the Praça

de Sé at the Bahia, I see around me people of every shade: blacks; whites;

mulattoes; morenos; caboclos. This is the reality of Brazil: a new race is evolving

here in the tropics, not a pale imitation of the Europeans."

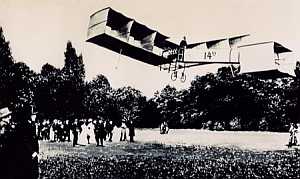

"Alberto

Santos Dumont has set all Brazil awhirl."

"Alberto

Santos Dumont has set all Brazil awhirl."

"It's unnatural. It's dangerous — "

"And it's grand!"

Brazilian national pride had soared in the weeks since Santos Dumont made the first recognized flight in Europe, covering 722 feet in his 50-horse-powered "aerodromo."

![Engenho, Pernambuco [35]](../images/engenoJunco.jpg) Long

before they reached Usina Jacuribe, the air reeked of sugarcane.

Long

before they reached Usina Jacuribe, the air reeked of sugarcane.

"Well, my inventor of aerodromos, what do you think of this machine?"

Juraci looked at the hillocks of cane in the mill yard. "All this will be crushed?"

"Everything you see and many, many tons more."

"There will be a mountain of sugar!"

![Brazilian Air Force, World War II, P-47 [1]](../images/p-47_4.JPG)

![Brazilian Expeditionary Force, World War II, Emilia-Romano, Italy [2]](../images/Brazexpeditionforcefromwiki.jpg) In

Northern Italy, Roberto's squadron flew in support of a Brazilian land

force of 25,000 men attached to Mark Clark's Fifth Army along the "Gothic

Line." Hitler had predicted the Brazilians would be ready to take the field

against him the day Brazil's snakes took to smoking pipes; consequently the

Brazilian soldiers called themselves "the Smoking Cobras."

In

Northern Italy, Roberto's squadron flew in support of a Brazilian land

force of 25,000 men attached to Mark Clark's Fifth Army along the "Gothic

Line." Hitler had predicted the Brazilians would be ready to take the field

against him the day Brazil's snakes took to smoking pipes; consequently the

Brazilian soldiers called themselves "the Smoking Cobras."

![Juscelino Kubitschek, Brasilia presentation, 1959 [3]](../images/JKaddressarchivesbrasilia.jpg) "Dreamers,

all of them!" Amilcar declared."A city built on nothing, rising out

of nothing..."

"Dreamers,

all of them!" Amilcar declared."A city built on nothing, rising out

of nothing..."

The day before at Anapolis, five hundred miles north of São Paulo, Dr. Juscelino Kubitschek had signed a proposal to build a new capital on the high central plateau.

"You're right, Pai, Brasília has long been a dream — "

"Another El Dorado."

"No, Pai — a new beacon for Brazil."

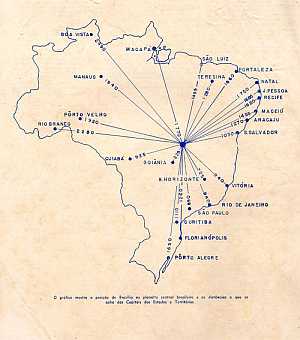

Roberto

picked up a saltcellar and dramatically placed it on front of him on the table.

"Brasília!" he announced. He drew a line from it across the

clothe with a fingernail. "Rio, six hundred miles southeast." Then

he drew five more lions radiating from the salt cellar in different directions.

"Roads to unite the country, to draw our people together, The new capital,

he declared passionately would alter the colonial mentality, put an end to the

inertia that kept Brazil clinging to lands near the coast.

Roberto

picked up a saltcellar and dramatically placed it on front of him on the table.

"Brasília!" he announced. He drew a line from it across the

clothe with a fingernail. "Rio, six hundred miles southeast." Then

he drew five more lions radiating from the salt cellar in different directions.

"Roads to unite the country, to draw our people together, The new capital,

he declared passionately would alter the colonial mentality, put an end to the

inertia that kept Brazil clinging to lands near the coast.

![Pele, No 10, World Cup 1958, FIFI, Foto-Net [5]](../images/schweden58_fifa_542_1702_full-lnd.jpg) "Pelé!

Pelé! Pelé!" Three young boys, two of whom were sons of Anacleto

and MAria, played outside in the dirt, kicking a soccer ball. Futebol

was an obsession with them, playing with as much gusto as if they were members

of the national team that had captured this year's World Cup.

"Pelé!

Pelé! Pelé!" Three young boys, two of whom were sons of Anacleto

and MAria, played outside in the dirt, kicking a soccer ball. Futebol

was an obsession with them, playing with as much gusto as if they were members

of the national team that had captured this year's World Cup.

Francisco

Julião, a 43-year-old Recife

Francisco

Julião, a 43-year-old Recife

lawyer was one of the few willing to represent the peasant and small farmer. The society called simply "the League," by its members, in the mouths of its opponents became the "Ligas Camponêsas," the Peasant Leagues, evoking memories of a failed attempt by Brazilian Communists to start a peasant movement.

![Casa Grande and Senzala [7]](../images/Engenho5.jpg) As

Juraci looked back at the deserted house, he found himself thinking of the Casa

Grande.

As

Juraci looked back at the deserted house, he found himself thinking of the Casa

Grande.

For centuries, the mansion had symbolized the conquest of l;ands, and the senzala and the shanty the conquest of man. Today, the Casa Grande and the home of Anacleto Pacheco, worlds apart and yet inseparable, were both empty and deserted. But God knew, the way of life they both represented hadn't changed.

![Pau-de-arara, truck transport for Brasilia workers 1950s [8]](../images/paudearara.jpg) "Go?"

"Go?"

"With the pau-de-arara." In the "parrot's perch," roosted in the back of a truck, a man could ride for a thousand miles and more to areas where there was work — and hope.

"To São Paulo?" Juraci asked.

"No, Dr. Juraci. Brasília! That's where the jobs are."

![Rain forest, Brazil, wet season [9]](../images/Manausforest5.jpg) In

the rain forest during the wet season from October to April, the torrential

downpours brought work to a standstill, and stranded road builders had to be

supplied by parachute drops of food and medicine. Across the cerrado, a sea

of mud also slowed down construction, but wherever work could continue it did,

the struggle to clear the first the same as in ages past, inch by inch.

In

the rain forest during the wet season from October to April, the torrential

downpours brought work to a standstill, and stranded road builders had to be

supplied by parachute drops of food and medicine. Across the cerrado, a sea

of mud also slowed down construction, but wherever work could continue it did,

the struggle to clear the first the same as in ages past, inch by inch.

![Rain forest, Brazil, clearing trees with fire [10]](../images/Rainforestburned.jpg) The

trailblazers were followed by six-man gangs with machetes and saw, slashing

through the undergrowth, cutting loose cablelike lianas, felling tree after

tree, selecting the best wood for lumber and leaving the rest for the fires,

the smoke from the conflagrations visible for miles behind.

The

trailblazers were followed by six-man gangs with machetes and saw, slashing

through the undergrowth, cutting loose cablelike lianas, felling tree after

tree, selecting the best wood for lumber and leaving the rest for the fires,

the smoke from the conflagrations visible for miles behind.

Where

the destruction was complete, bulldozers and Caterpillars lurched forward to

shove aside charred timbers and uproot blackened stumps. Only then could the

engineers and laborers begin preparing the roadbed for the gravel-surfaced highway

that would link Brasília with the mouth of the Rio das Amazonas.

Where

the destruction was complete, bulldozers and Caterpillars lurched forward to

shove aside charred timbers and uproot blackened stumps. Only then could the

engineers and laborers begin preparing the roadbed for the gravel-surfaced highway

that would link Brasília with the mouth of the Rio das Amazonas.

![Xavante, Brazil [11]](../images/xavante2.jpg) "Xavante?"

da Silva asked softly, from the edge of the canes.

"Xavante?"

da Silva asked softly, from the edge of the canes.

With a slight motion of his arm, Salgado beckoned Roberto forward.

A lone Xavante stood on the opposite bank, motionless, his eyes turned toward them. A young warrior in the prime of manhood. His naked body was streaked with urucu dye. One hand held a long bow, the other a war club.

![Candido Rondon, Brazilian engineer and explorer [13]](../images/crando02.gif)

Colonel Cândido Mariano Rondon, an army engineer and explorer, absolutely forbade the slaying of the tribes whose villages lay along the route of the telegraph line. "Die if necessary, but never kill," Rondon, himself half native, told his men.

Rondon began a lifelong battle against those who saw the survivors of the great native tribes as bestial and deserving extinction, especially is they occupied lands where these was rumor of gold and diamonds or where the forest could be destroyed to make way for cattle.

![Madeira-Mamore Railroad, Rondonia, Brazil [14]](../images/MadeiraMamoreRail12.jpg) Six

thousand men died during the five-year construction of the Madeira-Mamoré

railroad. Izaias Salgado was there when a gold spike was driven home and the

work completed. One year later, the rubber boom collapsed, exports from the

Far East surpassing those of the Amazon Basin. Within a decade, the railroad

was abandoned.

Six

thousand men died during the five-year construction of the Madeira-Mamoré

railroad. Izaias Salgado was there when a gold spike was driven home and the

work completed. One year later, the rubber boom collapsed, exports from the

Far East surpassing those of the Amazon Basin. Within a decade, the railroad

was abandoned.

![Orlando, Leonardo e Cláudio Villas Bôas, crica 1950, arquivo da família Villas Bôas autor: J.P [15]](../images/VilasBoasWIki.jpg) "Within

a year, a quarter will be dead," Bruno said. "We ask too much of them.

We take a stone ax out of their hands, give them a shirt and trousers, and expect

them to step into our word just like that. The Vilas Boases know what they're

talking about when they say it takes fifty or sixty years for a tribe to adapt

its way of life."

"Within

a year, a quarter will be dead," Bruno said. "We ask too much of them.

We take a stone ax out of their hands, give them a shirt and trousers, and expect

them to step into our word just like that. The Vilas Boases know what they're

talking about when they say it takes fifty or sixty years for a tribe to adapt

its way of life."

![Flauta Uruá. Aldeia Kamaiurá, Alto-Xingu, photo Noel Villas Bôas 1998 [16]](../images/Xingu.jpg) The

Vilas Boas brothers had founded the Xingu Indian Reservation along the river

of that name in Mato Grosso. The brothers contacted a dozen small tribes in

an area of more than 10,000 square miles, living with them and gaining their

respect — and beginning a struggle to have the region declared a federal

reservation.

The

Vilas Boas brothers had founded the Xingu Indian Reservation along the river

of that name in Mato Grosso. The brothers contacted a dozen small tribes in

an area of more than 10,000 square miles, living with them and gaining their

respect — and beginning a struggle to have the region declared a federal

reservation.

![Candangos, Brasilia inauguration 1960 [17]](../images/caminhao.jpg) An

endless parade was inching along the mall toward the Plaza of the Three Powers.

Ten thousand men, led by a dozen bands...They were the men who had built Brasília:

the candangos.

An

endless parade was inching along the mall toward the Plaza of the Three Powers.

Ten thousand men, led by a dozen bands...They were the men who had built Brasília:

the candangos.

![Brasilia, 1960 [18]](../images/historia-de-brasilia-8.jpg) That

evening Amílcar da Silva stood alone at a window on the twentieth floor

of one of the twin skyscrapers. Amílcar gazed out, not at the gleaming

city below, but far off into the distance, to where the cerrado was darkening.

That

evening Amílcar da Silva stood alone at a window on the twentieth floor

of one of the twin skyscrapers. Amílcar gazed out, not at the gleaming

city below, but far off into the distance, to where the cerrado was darkening.

![Bandeirante, sculptor Murio Toledo [19]](../images/BandeiranteParnaibaMurioToledo.jpg) This

vast sertão, not only over the next hill or across the next river, but

deep within the soul. A call to Paradise or to Hell for our forefathers. Were

they out there now, Amador Flôres da Silva and Benedito Bueno —

all who had opened the way for this conquest? Were the old bandeirantes gazing

back in awe at this city — this El Dorado they had sought for so long.

This

vast sertão, not only over the next hill or across the next river, but

deep within the soul. A call to Paradise or to Hell for our forefathers. Were

they out there now, Amador Flôres da Silva and Benedito Bueno —

all who had opened the way for this conquest? Were the old bandeirantes gazing

back in awe at this city — this El Dorado they had sought for so long.

![Canudos, Cocorobo Barrage, 1980 [1]](../images/CanudosBarrage.jpg) For

forty years, Canudos lay below Cocorobó barrage, nothing visible except

a grassy island, where goats and sheep grazed, rowed over by a herdsman. The

year 1996 brought one of the worst drought in memory. Week after week, the waters

of Cocorobó fell, until the ruins of Canudos began to emerge under the

red, hit sun.

For

forty years, Canudos lay below Cocorobó barrage, nothing visible except

a grassy island, where goats and sheep grazed, rowed over by a herdsman. The

year 1996 brought one of the worst drought in memory. Week after week, the waters

of Cocorobó fell, until the ruins of Canudos began to emerge under the

red, hit sun.

![Canudos archaeological dig, post 1996 [2]](../images/Canudosemerged.jpg) Most

prominent were the remains of the Counselor's church, standing on one of the

knolls. Two arches and supporting walls of the huge rectangular sanctuary had

survived cannonades from the Whitworth batteries and "God's Thunderer."

Below the church lay the trench where Antônio Paciência stood with

the handful who fought until the end of their world.

Most

prominent were the remains of the Counselor's church, standing on one of the

knolls. Two arches and supporting walls of the huge rectangular sanctuary had

survived cannonades from the Whitworth batteries and "God's Thunderer."

Below the church lay the trench where Antônio Paciência stood with

the handful who fought until the end of their world.

![Canudos, Trench excavation [3]](../images/CanudosTrench.jpg) It

was now recognized that the 20,000 who died were not a bandit rabble but landless

peasants scourged by drought and abandoned by their government. Most were black

people and mulattoes scorned by racist elites of the day, who favored a "whitening"

of Brazil and weren't against exterminating a barbarian race in the backlands.

It

was now recognized that the 20,000 who died were not a bandit rabble but landless

peasants scourged by drought and abandoned by their government. Most were black

people and mulattoes scorned by racist elites of the day, who favored a "whitening"

of Brazil and weren't against exterminating a barbarian race in the backlands.

Padre Antonio "Tôninho" Paciência looked at the trench, where his forbear had perished. "A hundred years since the last shot was fired," he said. "And still the battle goes on."

![Boia fria, "cold meal," photo by Abelardo Alves [4]](../images/Boia_fria.jpg) Most

residents of Magdalena labor for a pittance as field workers; bóia

fria, they're called, literally "cold meal," for they head off

at five in the morning, eat a cold lunch beside the canes, and return around

seven in the evening. By the time they get home, their supper of rice, beans

and manioc is cold.

Most

residents of Magdalena labor for a pittance as field workers; bóia

fria, they're called, literally "cold meal," for they head off

at five in the morning, eat a cold lunch beside the canes, and return around

seven in the evening. By the time they get home, their supper of rice, beans

and manioc is cold.

![MST flag, Brazilian landless rural workers movement [5]](../images/MSTFlag.jpg) The

sharecropper, Luiz Alves de Sá took out the MST flag and hoisted it to

the top of the pole.

The

sharecropper, Luiz Alves de Sá took out the MST flag and hoisted it to

the top of the pole.

A cheer rose from all who lifted their eyes to the red banner floating against the sky.

Padre Tôninho bad them join in a prayer of thanks.

When the worship ended, Luiz Alves said what was on everyone's mind: "Nothing will get me off this land — my land."

![MSTBrazilian land movement, occupation, Rio Grande do Sul 1998 [6]](../images/MST2.jpg) A

few more shots in the air and the justiceiros roared off.

A

few more shots in the air and the justiceiros roared off.

The defenders of Affonso Ribeiro gave a mighty shout. Husbands hugged their wives. Parents grabbed children and hoisted them on their shoulders for a victory march through the camp. It was not over, they knew, but they'd won the first battle. The soil they trod was a step closer to being their own.

![Street kid, Brazil, by Carf [7]](../images/streetkidcarf.jpg) "The

army of the streets is constantly on the lookout for recruits. It takes them

at any age and moves them rapidly through the ranks. In no time at all, the

kids are in the front lines, fighting for their lives," says Dona Mariette.

"The

army of the streets is constantly on the lookout for recruits. It takes them

at any age and moves them rapidly through the ranks. In no time at all, the

kids are in the front lines, fighting for their lives," says Dona Mariette.

At

the dawn of the twenty-first century, Mariette da Silva is in the vanguard of

a new revolution. It required no force or visions of El Dorado but began with

one man who changed the conscience of Brazil.

At

the dawn of the twenty-first century, Mariette da Silva is in the vanguard of

a new revolution. It required no force or visions of El Dorado but began with

one man who changed the conscience of Brazil.

Herbert "Betinho" de Souza opened the nation's eyes to the misery around them when he launched Citizen Action Against Poverty and for Life.

"Betinho gave face to millions who were pariahs in their own land. No one expects poverty to end tomorrow. The rich are getting richer and the poor poorer than ever, but they are no longer faceless. When the weakest and littlest one gives up life for lack of food, we cannot say we didn't know," says Dona Marietta.

![Canoe, Brazil rain forest [10]](../images/AmazonCanoe2.jpg) Tajira

beached the canoe and bounded across the plaza, shouting a greeting as he ran.

The past years could have been an ordeal for an Old Devil, with his world turned

upside down, but it was not so. Instead he knew only joy, and sometimes a tinge

of regret that he had not had a son of his own.

Tajira

beached the canoe and bounded across the plaza, shouting a greeting as he ran.

The past years could have been an ordeal for an Old Devil, with his world turned

upside down, but it was not so. Instead he knew only joy, and sometimes a tinge

of regret that he had not had a son of his own.

"While this old devil has strength left, I want us to leave Kaimari and take the bus from Pimento Bueno. It will be a long. hard journey."

"Where are we going?

"To find your father's people."

![Brasilia Cathedral [11]](../images/Brazil_Brasilia_01.jpg) They

reached the futuristic capital built in 1,000 days in the late 1950s toward

sunset. The Candangos are fiercely proud of the white marble palácios

and towers riding on the savannah. — For a boy from the forest of Kaimari,

visiting Brasília was like being on the moon or Mars even; everything

was a wonder to him.

They

reached the futuristic capital built in 1,000 days in the late 1950s toward

sunset. The Candangos are fiercely proud of the white marble palácios

and towers riding on the savannah. — For a boy from the forest of Kaimari,

visiting Brasília was like being on the moon or Mars even; everything

was a wonder to him.

![Pataxo Indian, Brazil [11]](../images/PataxoWiki.jpg) Arací painted Tajira's face with lines of red urucu dye. Then she helped

him put on a headdress crowned with the brilliant red and blue feathers of Macaw...

Arací painted Tajira's face with lines of red urucu dye. Then she helped

him put on a headdress crowned with the brilliant red and blue feathers of Macaw...

"We ask God to forgive the sins committed against the human rights and dignity of the Indians, the first inhabitants of this land, and the blacks who were brought to this country as slaves..."