CALIFORNIA

Jack Cunningham

"I saw a pretty little stream of water in Spokane that made me homesick. I caught the first freight I saw that was headed for Missouri and home."

CALIFORNIA

Jack Lindsay

Was 17, from Warren, Ohio to California.

“I, to this day have never been so hungry, so dirty, so tired, so sleepy, so hot in my life since, and I have been in combat in the military. The service didn’t even come close, but only in one respect and that was being tired.”

CALIFORNIA

James Daly

Texas Red.. The meanest. While riding the tops on a reefer car going through Arizona kicked and stomped me and another 15-year-old into the ice compartment and locked it. We would have died if some 'bos who saw the action hadn’t let us out.”

CALIFORNIA

James Hull

High School graduate

Left without previously informing our parents. “Imagine terror for our mothers and fathers”

Freight trains often didn’t run any regular schedules between some towns. It was difficult to find out the departure times.

The Tank… Salt Lake City… a large holding cell with about ten wooden bunks bolted around the sides. Told that we could stay till Monday or take a “floater” – a ride to the edge of town with instructions to keep on moving

CALIFORNIA

James Overby

12- 19

1928-1935

“I really didn’t have a home. My folks lived in and around a little town of Rogers, Arkansas. My Mom died when I was five years old and my Father took off shortly after that, I guess for parts unknown.

I was raised by an aunt on my Father’s side, who had a real mean husband and they treated me like I was a dog. I stayed with it until I was about 12 years old and then I took off on my own and I was on my own from then on.

I remember shortly after I was 12, I was driving four head of mules hitched to a logging wagon hauling logs to a saw mill.

I was working in Oklahoma, I think it was 1935. I was plowing one day and I noticed a building, looked like a shed, sticking up out of the ground. I asked the boss about it and he said, No that its a two story building that’s been covered with sand within just the last couple of years.” So they really had some sand storms back in that time.

Raiding a water melon patch. . . I was going full bore and this black boy passed me like I was backing up. I can still see the Johnson grass seed flying like a jet stream as he went by, never saw him again.

Arrested: Took us to jail and searched us, being just a youngster they didn’t do too good a job searching me because I had a .38 pistol under my belt.

Scattering coal for poor kid: We probably rolled enough coal to last those people a couple of years.

“You can see that I wasn’t always a good boy but I never did get in trouble really."

CALIFORNIA

James Pabian

One of Hollywood’s most sought after and famous animators. He was also a cartoonist whose comic strip appeared in newspapers across the country.

In late 20s, Jim had left home in Rochester, NY, with a cousin on an exploratory trip. They had a ramshackle car and a lot of hope. Finding no work for artists on the west coast, they headed home. They sold the old car to stay alive and began hitching back to Rochester. They found themselves in a camp of sorts somewhere in Colorado.

A family, not much better off than Jim and his cousin, offered to share the food they were preparing over the campfire. Jim and their 16-year-old daughter found much to talk about during the evening.

In their conversation, Jim mentioned that he and his cousin were headed back to Rochester on $2.60. They were counting on good luck, the kindness of strangers and help from the Lord, not necessarily in that order.

A slight drizzle began to fall. Jim removed a rain slicker from his knapsack, putting it over the girl's shoulders. They continued to talk until the girl’s parents called her to their space in the campground.

Awakening next morning they had neither heard nor seen the family leave. Adjacent to the area they had stalked as their turf the night before there was Jim’s rain slicker neatly folded and resting on a rock. There was no note. What needed to be written?

Jim picked up the slicker to put it in his pack. A half dollar had been tucked into the pocket.

CALIFORNIA

James San Jule

"de-princed"

Father was a millionaire in Tulsa, OK, oil land leasing. My father had arranged for me to go to Amherst and Harvard Law school.

Crash of 1929 came along and destroyed him. Physically he was never able to work again. Father retreated into inability to do anything.

I'd read Richard Halliburton's adventures. It was a helluva lot better than what we were doing.

I left home in 1930, age 17, rode freights for 2 1/2 years

Worked on oil fields as a roustabout… terrible job for a 17-year-old who was de-princed.

To Houston to try for a job. I lived in Old Spanish prison for a couple of months and survived by begging.

New Orleans to New York Lived in boxes behind packing houses.

Hopped freight trains west again to docks; eventually became a union organizer.

"I was headed for Wall Street and retirement at Westchester. I became a leader in a big left wing union."

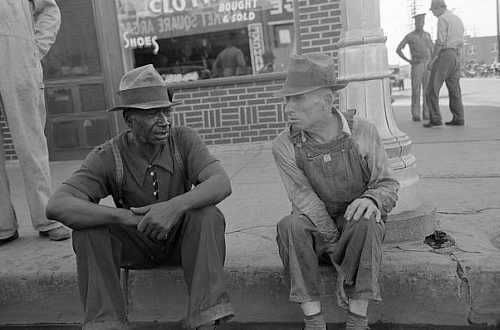

"I was about as bigoted as you can be. A black guy saved my life: I was being attacked by some older bo's, probably for sexual purposes. Black guy intervened. The incident changed my outlook."

Hunger, loneliness, dirt... I remember.

CALIFORNIA

Jim Johnson

12-18

1934-1936

In December, on one of several boxcar trips across Snoqualmie Pass to Ellensberg, several hobos on my train froze to death. I left the train and crawled through snowdrifts, tunneling part of the way to a small restaurant where a kind doctor treated my badly frozen feet. He packed my feet in snow and it was over a month before I could walk again.

I hopped a freight south determined to find my mother and brothers again. Intense heat while riding on a flat car ( all boxcars were locked) across the Great Salt Lake of Utah, nearly cost me my life. A kindly black hobo saved me when I passed out and fell across the tracks.

CALIFORNIA

Joseph Rieden

17 in 1930

Coming into town, the train came to a stop, jerked ahead; I believe to take up the slack between cars. Just then a young man stuck his head out the door. The door slid shut and off came his head, fell to the ground. The body was still in the car, the police came, questioned all ten of us and let us go. After all these years, I can still vividly see this.

Back on the train, we sat in the doorway. Some guy was bothering two young women, so they complained. Ralph and I got up, went over and told him off and what for. He behaved from then on. Soon we were approaching another town.

The girls were all dressed up in cowboy outfits and stood next to us in the doorway. Suddenly one took her gun out and shot 3 out of 5 crows on the telegraph wires. We all had a little more respect for them after that.

A couple miles back we noticed two yard bulls with rifles climbing aboard dressed in black and white. Everybody got off and hid in a wheat field. One black boy was shot at in the wheat, all you could see was the wheat parting when he ran through.

CALIFORNIA

Kermit Parker

middle class/young innocent

traveling 2,500 miles to attend electrical college, where thought fee was $25 = registration only

There were no mainline railroads serving Walla Walla, so I employed my second choice of transportation, hitch-hiking, to get to Pendelton, Oregon, where I could connect with the Union Pacific mainline. I wasn't really an old hand at riding freight trains, so this trip would be called, in modern terms, "on the job training."

I wasn't alone on this venture; there were quite a few other men waiting for the "east bound," when I located the railroad yards. Pendelton was a "division point," so all freight trains stopped to change engines and crews.

The yards were very complicated, with dozens of parallel tracks filled with freight cars to be made up into trains. An engine could be coupled to one end of a long string of cars, a caboose on the other end, and a train would be ready for departure.

In that maze of cars I had no way of telling which string of cars were made into trains and which were not. One of the "passengers" awaiting the "east bound" took pity on me and showed me how to tell when the train was ready for departure, where to go to get on and what part of the train to board.

We walked to the end of the yards and found a locomotive being coupled to a long string of cars that terminated in a caboose. This was the "east bound" preparing for departure. We walked along the train until we were near the back end.

It was late in the evening and almost dark so it was getting more difficult for my teacher to see what he was looking for, which was an empty boxcar with the door latch open. He explained to me that the empty cars were placed near the back of the train, and usually had the door latches open. If the latch was closed and had a seal attached, it meant that the car contained merchandise and it was a federal offense to break a seal.

By this time the train was moving a little faster then I could run, but when the designated car got to my friend, I was several cars ahead of him. He easily caught the grab iron and swung up on the bed of the car. As he came by me, I ran along beside the train holding my suitcase up as high as I could without losing my balance. As he passed, he reached out and grasped the suitcase by the handle and swung it up beside him. The back end of the car was rapidly approaching. As it went by I seized the grab iron with both hands, the momentum of the car swung me up and placed both feet in the stirrup. I was aboard the southbound, next stop, Ogden, Utah.

On the way across town from the hobo jungle to the rail yards my friend had been instructing me on the safest way to board a moving train. There was no "safe" way to get on a fast moving train, but with some understanding of the basic facts, it was much safer than without them.

"Once you decide to take hold of the grab iron, you grasp it with both .. hands and be ready to hold your entire weight, in case you miss the stirrup with your feet. If you should miss your body will swing back down, your feet will hit the ground and the momentum of the train will swing you back up for a second try at the stirrup, but if you lose your hand hold you are in for an end-over-end tumble, sometimes terminating the trip."

A grab iron is a step made from three-quarter-inch round steel bar, about eighteen inches long and placed four inches from the side of the car, its purpose is to support a man getting on or off a freight car.

From each end of the car, we eased our way around the piles of lumber and met in the center. It was quite pleasant there. We could watch the passing country on either side of the train. The piles of lumber made a good windbreak, the sun was nice and warm so the ride was most enjoyable. The fact that we were riding in the most dangerous place on the train didn’t reduce our pleasure, because we didn't realize that if the train made a sudden stop, the lumber wouldn’t, making us a very messy situation for the cleanup crew.

My favorite observation seat on a moving train was the top of a boxcar seated on the end of the walkway with my feet dangling between the cars and one arm wrapped around the brake wheel that was located next to the walkway on top of the car. This location was especially attractive in the evenings just after sunset.

The roar of the steam locomotive, sometimes a half mile or more ahead, the sway of the car, the clickety clack of the wheels passing over the rail joints, the wind blowing in my face as the train sped along at forty or fifty miles an hour, was a thrill I have never forgotten. Of course the occasional cinder in the eye from the coal the engine was burning, I also remember but without the fondness.

Instead, all I saw for miles on end were abandoned farm buildings with the dirt piled on the sides like snow drifts. There were few people or animals to be seen. The few trees there were, were leafless and appeared to be dead. The scene was the same for miles and miles, a world that had been abandoned by both man and beast. The houses and farm equipment was just as they had been left, except now they were semi-buried under the great drifts of fine dust. I didn't realize that I was witnessing one of the greatest tragedies of American history; the Dust Bowl of the 1930's.

So here I was back on the street again in the big city of Chicago with no place to go except home, which was a couple thousand miles due west.. Now I had money in my pocket and I felt as long as I had made the trip out there, the least I could do was to see as much of Chicago as I could before returning home. So I sat out on a two day unguided sightseeing tour of the city.

I visited the sight of the 1933 Century of Progress World's Fair. Most of the buildings were still there, but were being used for other purposes. I spent some time in the Museum of Science and Industry and Natural History. Walked the streets of the "loop", and got a sore neck looking up at the skyscrapers. Watched the elevated trains, called the "L", rattle their way around downtown, on their steel trestle network, a story above the the traffic jams on the streets below. I could not resist the urge to tilt my head back as far as it would go and gaze up at those unbelievably high buildings.

Of course this procedure immediately identified me as a hick from the sticks, because no city dweller would be caught with their head back, looking up at the buildings. While engaged in this unusual pastime, I saw to my amazement what at first looked like one of the skyscrapers, lying on its side floating above the city. Each end came to a rounded point, and suspended below it were four large engines, two on either side.

In large letters down the side were the words GRAF ZEPPELIN. What a thrill to see something that I had read about, had seen many pictures of, but never thought I would get to see t It was the famous German, lighter than air, commercial airship. I don't think that anyone else in downtown Chicago saw that sight that day, they were too sophisticated to look up.

As a matter of pride, blinders rode only the status trains such as the express mails or the red-ball passenger trains (like the Wabash Cannonball or the Cotton Belt Blue Streak). Most blinders were men in late adolescence and young manhood.

As they used to say of fighter pilots: there were old blinders, and bold blinders, but no old, bold blinders; most of them quit or died young.

Although the "Okies" had not yet began pouring into California, the state was hostile to hobos, especially the Los Angeles area. The Lincoln Heights jail in LA was famous for its abusive treatment. We heard of sexual abuse of young boys by both jail inmates and jail personnel.

I rode the Texas & Pacific, Cotton Belt, Denver & Rio Grande Western (the old "Dirty, Ragged and Greasy") and the Missouri, Union, and Southern Pacific lines. My most memorable rides were on the UP "big boys." These were the largest locomotives ever manufactured-front cab, articulated engines specially designed for hauling long trains up long western grades. Each engine had sixteen ninety-six inch drivers and delivered over a million horses to the rails.

The double-headers out of the Cheyenne yards on the Sherman grade was the most impressive show of power I have ever known; at the crest of the grade, a double-header would make the earth tremble for a mile on either side of the tracks. (I have since learned that when a big boy double-header made the last scheduled run up the Sherman grade, train buffs from all over the world assembled at the crest to see and hear and feel the farewell performance of a truly great train.)

My impression was that hobos quickly recognize a novice at the trade, and offered survival seminars and demonstra-tions - how to catch a boxcar (always jump for the front ladder; if you go for the rear ladder and miss, you go between the cars and under the wheels), the safe way to sleep standing up when riding tankers, how to tie oneself to the catwalks when riding the tops, securing the ice hatch doors on reefers (so you can’t get locked in), judging when a train is being made up and when it's ready to go, and so on.

Because of my age and small size, I never had to learn how to simulate deformities in order to beg successfully. I either hit on middle aged mother types for food or begged for postage stamps which in those days could be spent for food.

I was occasionally picked up by police who assumed I was a runaway that someone wanted; when it turned out that no one did, they always released me rather than take care of me.

Older hobos would warn us occasionally about the dangers of sexual assault, but no one ever tried to molest me. In part, I think, this was because young bums like me usually preferred to travel in small groups of three or four for mutual protection and support.

As a professional psychologist, I have been able to use my Great Depression hobo jungle experiences as illustrating the power of early experience to shape the tastes and personality of the adult.

The hobo jungle instills a certain accepting, Machiavellian attitude toward mankind. The attitude is something like, people may be "no damn good" but the issue of good or bad is moot; people are all there is for us. So we did not judge others-thieves, whores, murderers-we accepted them all for what they were, because there wasn't anything else.

On this particular June day in 1931, there were but two stacks clouding the sky. The historical announcement of Ford in 1913 establishing the minimum wage of $5 a day had grown to the unprecedented daily wage of $8 in 1930.

On this day changes developed – notices appeared on time cards which the workers used to clock in at each shift. DO NOT PUNCH TIME CARD UNLESS YOU AGREE TO A 50% CUT IN YOUR SALARY.

So wages were shaved down to $4.00 a day, along with a 50% reduction in manpower. My father was caught in the laid-off group. Our house payments could not be met so we lost the house.

My father rented a small house and was later assigned duty on the W.P.A. sewer project as a brick layer and was given a food and rent allowance for a family of four. (Father, mother sister and myself.)

School was out, I was fifteen years old and developing a wanderlust after receiving a post card from two of my caddy friends postmarked Los Angeles. They had hitch-hiked and were staying at a place called "Junipero Serra Boy's Club" similar to Father Flannigan's "Boy's Town".

Hitched a lift. At end driver got out, handed me the keys and thanked me for the ride. Escapee from a lunatic asylum.

CALIFORNIA

Lloyd Veitch

I just kept going from town to town on the harvest route. When one job played out there was always another in the next farming town. You’d just sit on the curb downtown and wait for a farmer to come along and offer you work.

We whites didn’t mix with blacks. We kept to whites because we never knew what the railroad men (brakemen, workers, railroad detectives) would do to the blacks and any whites with them. The railroad men were harsher with blacks than they were with us whites. I never witnessed physical harshness like beatings but a lot of times the railroad workers would let whites get by riding, but not the blacks

Did I witness any major historical events? I don’t believe I witnessed any unless participating in one of the greatest migratory movements in the history of the United States could be called that.

I saw the IWW in action. I believe the initials stood for “I will work. I won’t work” union. The IWW was made up mostly of out of work hoboes who had been laborers, all the way up to white collar workers – a mix. There were a vicious group who used clubs to make hobos pay to ride the trains. And they even went so far as to burn down the wheat fields of farmers who wouldn’t pay the fees the IWW demanded for “services rendered.”

My hoboing shaped the rest of my life because I learned to love my country by traveling around it. I appreciate the different kinds of people that go to make it what it is. I learned to size up people and situations at a glance; I learned to be self-reliant; I learned to value the roof over my head and the food in my belly; and I learned that freedom means responsibility.

CALIFORNIA

Louis Vincent

16-19

1933-1936

Adventure – to find myself

Came from a railroad family. Father used take me on trips with him (conductor) on freight train. Taught me do's and don'ts of riding freights. Learned other things by trial and error.

I was riding the blinds on a passenger train in Northern Alberta. Got tossed off by train crew at a little town, landed up in a hobo jungle, not to my liking so wandered into town, found the local beanery there. Had a dollar or so in my pocket, ordered a cup of coffee.

The waitress, some 15 years my senior, took a liking to me and fed me for three weeks and housed me. I managed to finally crawl back to the railway tracks and catch a freight out of town.

Another night, about 3 A.M. the freight we were on stopped for water at a small town, next to an "extra" gang, bunk cars, cook car etc. A couple of us climbed down following the aroma;. and got into the cook car. Swiped about 14 fresh pies in a window rack cooling, got them back up on top of the box car stuffed them under the running board and invited several more bums to "our " car for a feast.

Sat there going through the night eating raisin pies and skimming the empty plates off into the night like frisbees.

Often wonder how mad that cook was in the morning.

I was riding the "tender" on a freight one night up in the Peace River Country in northern Alberta. Asleep on the deck, warm because of preheating the water, woke up to the whistle. Stood up and looked over the top of the cab. A herd of wild horses on the track in the headlight, the glow from the open firebox lit up the engine. Whistle blowing in blasts to clear the track. A sight I will never forget.

CALIFORNIA

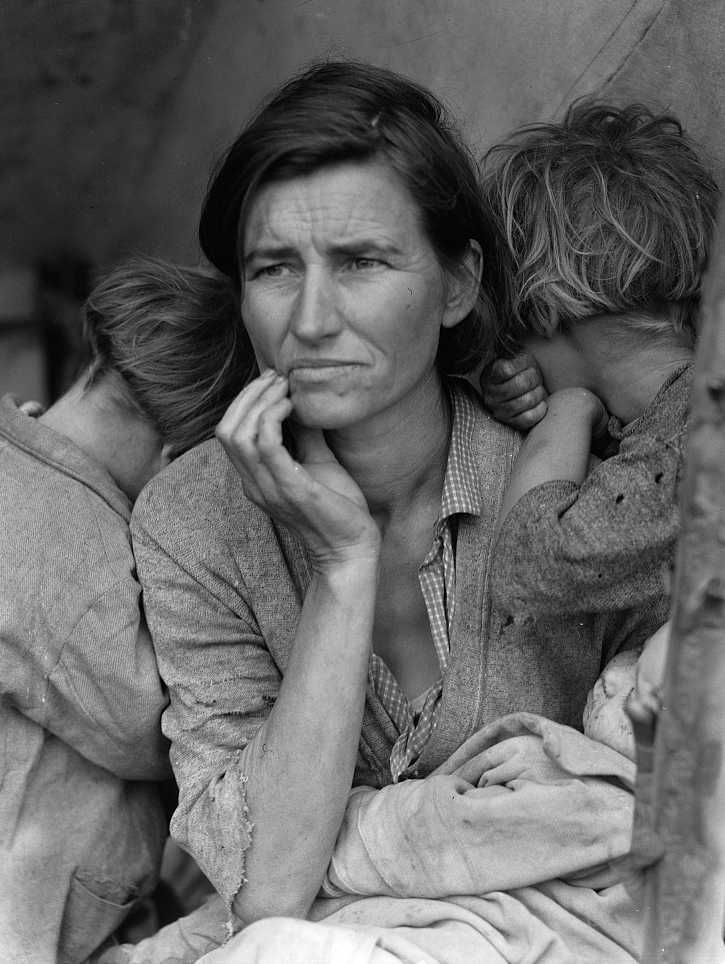

Lucille Asney

I was one of three children born to Mary Elizabeth Anderson. It was the Depression and my mother was left alone with us. She hitch-hiked all over California from job to job. She always loved trains and once decided to ride the box cars to Kansas City and back to Sacramento with my brother age 10. She was a small woman 4’10” and needed help getting up into the cars. She also carried her cat with her in a box – always. One thing she always said was how the other bums were willing to share their meals, around the camp fires and they treated her like a lady. My brother from age 4 sold crepe paper roses my mother made and that’s how she fed us.