CALIFORNIA

Manuel Krupin

17-18, Jewish

1932-1934

While sleeping in a reefer rudely awakened and thrown off the train, then realizing my glasses were left behind. Had trained myself to associate my actions and whereabouts with tell tale marks. The car I was sleeping in carried potatoes, was yellow, remembered four digits of number. Went to freight yard and made inquiries of the freight train that came in earlier in the evening and the yardmaster helped me locate the car even though it had been dissembled and assembled to go with another train.

Toledo, Ohio… “Finding myself in the midst of a riot. Tear gas in the air, live ammunition fired at unarmed people. Bayonet thrusts against desperate workers asking for reasonable pay and better working conditions. -- striking workers at the Auto Lite factory by the National Guard or Army Units, Toledo

I was in Washington DC and saw the Hooverville camps and when General MacArthur commanded the troops to destroy, gas and drive the Bonus March out of Washington. It left a lasting impression on me: An armed assault on men who had served their country and were peacefully pleading for help.

When I first started, a young high school graduate on a lark for some adventure, never dreaming I would have a real learning experience in economics, human relationships, politics, the real America and people’s compassion for one another.

Despair, broken homes, women with infants, disillusionment, bitterness, yet the willingness to commiserate with total strangers.

I learned the ability to look at people who were down and out with compassion rather than scorn. Not to question a person asking for food, because I know the humiliation and loss of dignity one experiences when they have to beg for food.

CALIFORNIA

Margaret Dehn

The year was 1935 and I was 16.

Riding the rails was an adventure in terror for me because of the bulls, who controlled the hitch-hikers – beating them with clubs, knocking them off the trains, rapping their knuckles so they would fall. We sometimes had to hide in cars containing, animals, manure garbage..."

CALIFORNIA

Michael Cleary

In 1933, December, we pulled into a freight yard at 6 in the morning at Des Moines, Iowa…

We always hopped off freight cars as they were pulling into the yards. If we rode all the way into the freight yards waiting for the cars to stop, the bulls would beat us up. It was a misty morning and around 20 degrees.

There was slush or light snow on the ladders, which were attached to the box car. A hobo slipped on the last step and his legs slid under the box car. The heavy steel wheels cut his legs off just a little bit above the knees. We rushed him to a nearby hospital and he lived.

I would put in a whole cord of wood into a cellar for 10 cents. You know what a cord of wood is? A pile of wood 4 x 4 x 8 ft. I also unloaded a car of coal into a hotel for $20. It took me three days – 1918. I also took care of an old man for $1.00 a day.

CALIFORNIA

Milton Holmen

Born 1920…Spent the 1937-38 school year as a freshman at the University of Arizona.

Because of the Depression, I could not get any kind of a job in Arizona, so I had planned to hitchhike to Minnesota to spend the summer helping my aging grandparents on their farm. A Tucson newspaper carried a classified ad asking for a man to ride with three women from Tucson to Minneapolis by helping to drive and contributing ten dollars toward gasoline purchases. I answered the ad, was accepted, and had an easy four-day drive to Minneapolis.

After a few days there, I hitchhiked 110 miles north to Upsala, where I spent a month with a grandfather who was recovering from cataract operations and another month with my mother’s parents on a small farm near Swanville, MN. In mid-August I started hitchhiking home, hoping the early summer’s murders had not completely ruined hitchhiking opportunities.

I got a ride to Minneapolis with a friend of my grandparents. Then, with a 30-pound suitcase full of clothes and food, got out on the highway and raised my thumb. After several hours I got a ride on a truck carrying canned groceries to Des Moines. I helped the driver unload the many boxes, and he let me sleep in the empty truck near the food warehouse. I caught a very early bus to the south edge of the city the next morning and again raised my thumb.

Both my timing and luck were good. I had been told that the best rides were with single people driving to a funeral— they started early, drove late, and wanted someone to talk to and to keep them awake. This man had started early, and drove me as far as Kansas City before turning east toward St. Louis.

Again I got on the road as early as possible, and again it paid off. This time I got a ride with a U.S. Secret Service agent in pursuit of people counterfeiting bills.

He could speak only in a whisper, which made it difficult for him to question anyone about whether they had seen any bills like his counterfeit samples, which had been found just south of where he picked me up.

I agreed to help him with his work if he would drive me farther south, and rode with him all day.

We stopped at grocery stores, service stations, and cafes in small towns along the highway where I showed clerks a couple of counterfeit bills and asked whether they had seen any others. On the edge of Joplin, MO, we found some more counterfeit bills, so my friend dropped me at a police station where he went to get more official help in pursuing the counterfeiters. He asked the police if their next patrol car going south could take me to the edge of town. They agreed, offered me a cup of coffee and a doughnut, which I consumed before getting the ride to the south edge of Joplin.

The next day I again held my thumb out for many hours. Another hitchhiker joined me just after noon.

He told me that he was a student returning to school at Arizona State College in Tempe. He pointed out the railroad yards nearby and said that he had arrived there on a train. He had detrained outside the railroad yards that morning and had hidden in the brush. As soon as the train stopped, several carloads of police with drawn guns took the hoboes away, saying that the local judge would give them ten days on the chain gang repairing roads.

He had bought lunch at a small cafe, and had learned that a freight train would be leaving early afternoon for El Paso. He suggested that we wait just outside the west fence of the yards and try to catch the train before it would be moving very fast. As we waited, we saw about fifty men waiting to catch the train. While it was taking on fuel and water, the men boarded it.

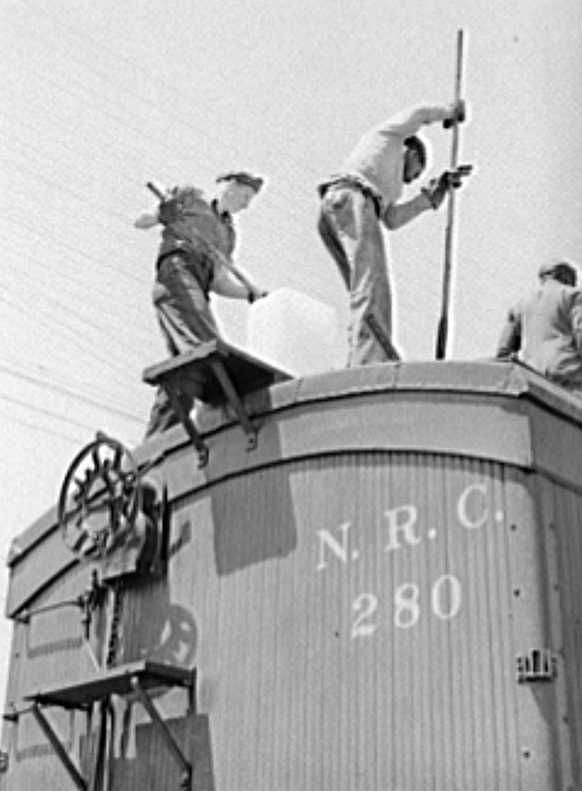

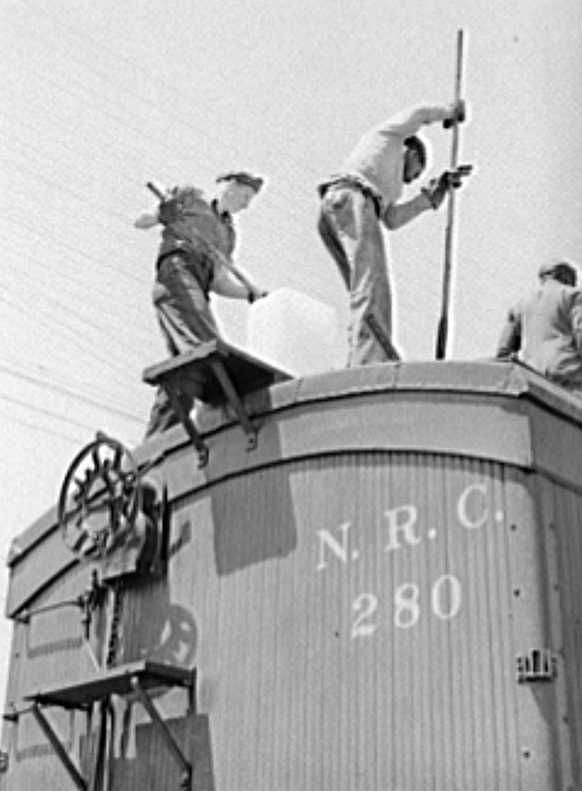

Then more carloads of railroad police came, herded the men into trucks, and drove them off. We stayed hidden in the creosote bushes until the engine of the train had passed us, then jumped onto ladders at the front ends of a couple of the last cars in the train. (If you try to jump onto the ladder at the back of a boxcar, you may be thrown under the wheels of the next car, but if you get thrown off the ladder at the front of the boxcar, you fall clear of the wheels.)

We saw a gondola open-topped car a short distance ahead of us and got into it without being seen by any of the train crew. We then discovered that a young African-American had hidden in a piece of sewer pipe in the car when the police came, so had evaded them. When the train started, many of the pipes slid, and one of them broke the man’s leg and pinned him against the end of the car.

My college friend and I flipped a coin. I lost. He stayed with the injured man while I went to look for a train crewman. The caboose, which was nearby, was empty, so I started forward, walking on the narrow catwalk on top of the cars. When I had walked on about a hundred cars, and jumped the spaces between them, a brakeman saw me. He drew a revolver and asked me what I was doing there. I told him that there was a man with a broken leg in the gondola near the rear of the train.

He told me to go back to the injured man and tell him they would take him off at the next town with a doctor. The train stopped in Monahans, TX, and the man was loaded into an ambulance. Many men got on while the train was stopped, and no one paid any attention to them.

We found an empty, unlocked boxcar while the injured man was being put in the ambulance. In it were about twenty other men and a couple of women. One of the men had a couple of cigar boxes. One box had a lot of green weed-like-looking material, and the other had several packets of cigarette papers.

The man with the boxes explained that he was a musician from El Paso, and that he made weekly trips to Monahans, as its railroad yards had a large supply of very good marijuana. He collected as much as he could between trains, and rolled it into “pokes” (about half a cigarette in size, but made of two cigarette papers) on the way back to El Paso. He had left his car in a small town just east of El Paso, because the local police were very hard on hoboes, and would confiscate his marijuana if they caught him with it

When he smoked some of the marijuana, I realized that it was the same product my mother had used for about ten years to alleviate coughing spells due to her asthma. She used a product called “Asthmador” which came in a small metal can. To use it she removed the small spoon-shaped lid, shook some of the material into the lid, put it back on the can and lit it with a match. Then she inhaled the fumes to alleviate the coughing. If it didn’t work, she would need a hypodermic injection of Adrenalin (spinephrine) which was more complicated and somewhat painful and dangerous.

About twenty miles out of that town, in the middle of nowhere, with the temperature about 100 degrees and no shade, the train stopped. The brakeman I had talked to and two other trainmen with guns herded everyone—about 60 men—out onto the highway. As my college friend and I started to get out of the gondola, he motioned for us to get in the gondola and stay down. At the next stop, the gondola and many other car were switched to a siding, and the train continued with only locked boxcars, so we moved to the top of one of the boxcars.

My friend and I lay on top of the catwalk, roasting in the heat, and breathing smoke from the engines up front. We rode on into the night, stopping several times to switch cars into or off the train. I awoke in the morning, looking down between the car I was on and the one immediately in front of it. I felt as though I were on an airplane, the ground was so far away.

I got on and off trains for several days as I passed through Colorado and on into Kansas. The Great Plains were something I had studied in geography but it hadn't looked like this in the pictures. There were no waving fields of grain no pretty little towns with parks that had lawns and trees

I soon realized that the extra noise that woke me came from our crossing a railroad bridge. My wake-up fright was caused by our crossing the Pecos River on one of the highest railroad bridges in the country.

We were sidelined often during the day and night for passenger trains which preempted the right of way. We stayed on the train, nibbling on some of the food my grandmother had packed for me, and we stayed out of sight as much as possible.

That night we arrived in El Paso. We had learned that the Texas Pacific Railroad, on which we were riding, had its yard in the east end of the city. The Southern Pacific, which we needed to get to Arizona, had its yard on the north end of the city. We had to get off the train as it slowed down for the east yards and find a way to the other yards. My friend and I figured that we had enough money to get a cab probably 75 cents) from one yard to the other, if we could find one.

We got off the train at a run and ran right into a policeman. He asked us, with his gun pointed at us, where we were going. We told him that it was to the two universities. He herded us into the back of a police car with another policeman driving, as we had visions of ten days on the chain gang. We drove about two miles before the police car stopped, nowhere near a police station.

They told us that a train would come out of the Southern Pacific yards in about half an hour headed for Tucson. They told us just where to stand to best catch the train. They said they would be back right after the train left to take us to jail if we were still there. Then they drove into the railroad yard and talked to some people working on the train. When the train came out of the yard, we got on a couple of cars near the front, and stayed away from a large group of mostly older men farther from the engine.

When the SP freight got to Bowie, AZ, trainmen again herded everyone off the train while it took on water and fuel. Again an armed brakeman asked how much money we had, and where we were going.

When we told him we had three dollars between us and were headed for college in Tucson and Tempe. He said loudly, “Get the hell out of the yards.” And softly: “And be under the water tower in ten minutes. You can get a hamburger for a dime across the street.” When the train pulled out, it had the two of us and one young black man headed for Ft. Huachuca, where he was a private in the 25th Infantry Regiment. Everyone else — about thirty men—were out on the highway trying fruitlessly to hitch a ride.

We got to Tucson without incident. I called home (for a nickel) and my father came to drive me home. I didn’t ride another freight train for a long time.

CALIFORNIA

Pat Piscatelli

Crossed country 27 times

In those days you had to be road smart like young people of today have to be street smart. You were classed as being a bindle stiff or balloon stiff.

Traveled light. A balloon was too cumbersome.

Smooth ride on milk trains. Avoided coal gondolas and tankers. They jumped the rails quite often and shook your kidneys to hell

Danger of freezing to death when trains scooped up water on the fly

Cheyenne, Wyoming had training school for bulls. It was considered the toughest place to get out.

Carried two railroad spikes as weapon in fist, when you had to belt someone. Better than brass knuckles. Really stunned them.

Biggest hobo jungle was in Stockton.

CALIFORNIA

Paul Booker

1931-32

age 15-16

Four men and I were in a reefer coming into the railroad yards of Longview Texas, when we heard loud gunfire. “My God,” one man said, “that must be Texas Slim. ( a railroad detective who was meaner than a rattlesnake).

We scurried out of the empty ice compartment to the top of the box car, and a few cars down, there was the dreaded Texas Slim shouting “You God damn son of a bitches, I’ll kill every one of you.”

I found out later that Texas Slim had boasted he had 17 notches on his gun, for each white man that he had killed. He said that he never even put a notch on his gun for a black man or a Mexican. We fled for our lives as this demon from hell fired wildly at us. Texas Slim was killed later by a young boy; alleged that Slim had killed his brother.

I was nearly killed going on to Seattle, when I was asleep between two box cars. The train gave a lurch, as it was moving slowly, and I fell to the ground, between the wheels. I frantically grabbed a steel beam and pulled myself up just in time.

Texas... dozens of men stood with guns at side of train; threatened to kill us if we got off.

I hadn’t eaten in over three days. An angel of a woman in her eighties saw my disheveled look and gave me one dollar.

CALIFORNIA

Paul Swanson

My one unforgettable experience happened while standing on top of a boxcar looking the opposite direction and something hit me in the back of the head and quickly turning around I was immediately faced with an overhead bridge coming at me. I belly flopped just in time to avoid being splattered over the boxcar. What hit me in the head were heavy duty ropes hanging down from a cable stretched across the tracks as a warning. From that time on I sat looking in the direction the train was going.

In a hobo jungle under a bridge near the railyards near Klamath Falls, Oregon, I met an old fella who had lost his leg riding the rails. Next morning I caught a freight bound for Sparks, Nevada. I was on a flat car as the train started to pull out when here came the one-legged gent. I extended my arm. He took my hand and swung onto the flatcar..

We sat side-by-side for a few miles before I felt like talking. "How did you get started on the bum, anyway?" I asked for openers. He gave me a long and steady look. Then he said: "You'll learn sooner or later that there are some questions you have no right to ask." We didn't talk much after that but in the ensuing years, I have thanked the old gent for that sage advice.....

The freight I was just pulling into the railyard at Ogden, Utah. You got to know that there was a training school for railroad dicks at Ogden and those bimbos practiced their fine art of busting your head with a billy if they caught you riding one of their precious freights. So you got off the freight as it entered the yard, walked around it, then hopped aboard on the fly as it left.

I jumped off as the train slowed and walked down the street that bordered the yard until I reached the other side. Then I saw the irrigation ditch. It was full of water and looked cool and inviting. But I had a nickel in my pocket and my stomach was growling so I walked down the road to a nearby store, intent on buying a candy bar. But I bought something else instead: a bar of soap! I returned to the ditch, stripped and dove in.

My stomach was in an uproar, berating me for having spent my entire fortune on a bar of soap. But lathering and splashing, a voice inside said: "You done good, m'lad!”

CALIFORNIA

Reino Erkkila

Spent summer of 1931 hoboing

I believe it had a hand in making me the liberal that I am. Not having finished college I became a longshoreman in San Francisco and an active trade unionist. Brief as my experience was, I have empathy for those I saw and met. Also for people in like circumstances today.

CALIFORNIA

Richard Myers

At three, I was placed in an orphanage by my mother who had to work in Pittsburgh PA. My father had run off when I was 2 months old.

At age 9, probably in July 1931, my mother lay dying in a hospital. She signed me over to the orphanage. The next day I was on a train to Iowa. A farm family picked me up and took me to their place. What they wanted for me was to teach their son to read.

They proceeded to beat and practically enslave me. After a month and a half or so, I took off. Dummy me, I went to the main highway. I was picked up in a park by the police, who took me back to the farm. I escaped in another week or two but this time headed for the Iowa River east. My goal was to get back to Pittsburgh. I had known I could walk 30 miles per day. Eventually I rode trains back to Pittsburgh. When I got to Pittsburgh, I went to the hospital to find that my mother had not died.

Anyway I finally found her. I found out that the orphanage had removed all records about me. The bureaucrats would not listen to my mother and find me and bring me back to her.

As a matter of pride, blinders rode only the status trains such as the express mails or the red-ball passenger trains (like the Wabash Cannonball or the Cotton Belt Blue Streak). Most blinders were men in late adolescence and young manhood.

As they used to say of fighter pilots: there were old blinders, and bold blinders, but no old, bold blinders; most of them quit or died young.

Although the "Okies" had not yet began pouring into California, the state was hostile to hobos, especially the Los Angeles area. The Lincoln Heights jail in LA was famous for its abusive treatment. We heard of sexual abuse of young boys by both jail inmates and jail personnel.

I rode the Texas & Pacific, Cotton Belt, Denver & Rio Grande Western (the old "Dirty, Ragged and Greasy") and the Missouri, Union, and Southern Pacific lines. My most memorable rides were on the UP "big boys." These were the largest locomotives ever manufactured-front cab, articulated engines specially designed for hauling long trains up long western grades. Each engine had sixteen ninety-six inch drivers and delivered over a million horses to the rails.

The double-headers out of the Cheyenne yards on the Sherman grade was the most impressive show of power I have ever known; at the crest of the grade, a double-header would make the earth tremble for a mile on either side of the tracks. (I have since learned that when a big boy double-header made the last scheduled run up the Sherman grade, train buffs from all over the world assembled at the crest to see and hear and feel the farewell performance of a truly great train.)

My impression was that hobos quickly recognize a novice at the trade, and offered survival seminars and demonstra-tions - how to catch a boxcar (always jump for the front ladder; if you go for the rear ladder and miss, you go between the cars and under the wheels), the safe way to sleep standing up when riding tankers, how to tie oneself to the catwalks when riding the tops, securing the ice hatch doors on reefers (so you can’t get locked in), judging when a train is being made up and when it's ready to go, and so on.

Because of my age and small size, I never had to learn how to simulate deformities in order to beg successfully. I either hit on middle aged mother types for food or begged for postage stamps which in those days could be spent for food.

I was occasionally picked up by police who assumed I was a runaway that someone wanted; when it turned out that no one did, they always released me rather than take care of me.

Older hobos would warn us occasionally about the dangers of sexual assault, but no one ever tried to molest me. In part, I think, this was because young bums like me usually preferred to travel in small groups of three or four for mutual protection and support.

As a professional psychologist, I have been able to use my Great Depression hobo jungle experiences as illustrating the power of early experience to shape the tastes and personality of the adult.

The hobo jungle instills a certain accepting, Machiavellian attitude toward mankind. The attitude is something like, people may be "no damn good" but the issue of good or bad is moot; people are all there is for us. So we did not judge others-thieves, whores, murderers-we accepted them all for what they were, because there wasn't anything else.

CALIFORNIA

Robert Lloyd

I was one of those unfortunates who had to ride the rails during the Great Depression, and have many stories to tell of the so-called 'trials and tribulations' we kids had to face, some of them quite gruesome.

I've run into tough railroad 'bulls', tough 'shacks' (brakemen) and also town marshals who were trying to make a name for themselves. A few times I've even gone "the rubber hose route" when I couldn't run fast enough to evade the tough ones.

Yet I've also met some of the nicest people of authority who've helped me find enough work to get by. It was not always the highest paying jobs - sometimes even the most menial kind. But I felt lucky to have them long enough to make a 'stake'.

I once saw as many as one hundred hoboes on one train. Some were whole families with small children. They had no place to go, nor anything to do when the got there. I saw the dead, empty, defeated look in they eyes, when they were told to move on, wherever they tried to stop.

I've cooked a meager meal over a jungle fire more than once, fully expecting the bulls to raid and destroy it before I had the chance to eat it. They seemed to get great fun out of slipping up on you and shooting holes in the can you had a stew cooking in, or when your coffee was just coming to a boil.

I saw more than one hobo just give up and drop from a train to his death when the train was moving fast. And I saw the time when it was hard not to follow their example, for hunger will cause a man to do things he would never think of with a full belly. But pride - or maybe the lack of guts to do so - kept me from it.

No, it wasn't easy for us. Many times gangs would take what little you had, leaving you feeling lucky to be left alive. Other times there would be enough of us to defeat them.

But the hard knocks of the Great Depression still leaves me with a fear for the future when I think of the 'myth' that people believe in today. That myth is the Federal Reserve, and how it will keep us from falling into the same pit that we were in back then. For, should the banks fail, as the Savings and Loans have, the Federal Reserve can also fail. Today, as it was in 1929, most of our wealth is on paper - stocks and bonds, etc. Wall Street controls us as it did back then.

We used to have a saying: Hoover blew the whistle, Mellon rang the bell, Wall Street gave the signal, and the Country went to hell.

We sang the song, Big Rock Candy Mountain, adding verse after verse to suit ourselves. It was a song to cheer us, and adding verses kept us in the mood.

The rattle of a flat-wheeled box car on the rails, the fear of being put off in the middle of nowhere. Sometimes the only place to ride would be under the car on the 'rods,' where we'd lay 'grain-doors' across to ride on.

Once, when "Butch" Taylor and I were riding thus, a tough brakeman lowered a 'fish-plate' - a square plate of iron used to the rail-onto a long wire. The iron would hit the cross-tie and bounce under the car where we were. It managed to hit the grain door several times, coming closer each time. Lucky for us, the train hit a steep grade and slowed down to a mere crawl so we could unload safely. But I'd heard of several who weren't so lucky.

Boys also had to watch the perverts, the Airedales as they were called. I usually carried a couple of railroad spikes in my pack to wedge a car door so it couldn't be easily opened, nor would it slide shut and trap me in it, should the train give a sudden jerk. And never was I without a knife or other kind of weapon for protection.

I learned early to never take off my shoes or coat unless I was sure I was alone. They had a way of disappearing while you slept.

CALIFORNIA

Robert Swain

In 1938 I was hitchhiking one night, trying to reach home which was 50 miles away, when a carload of fat sheriff's deputies picked me up in a county they did not have jurisdiction in, took me to the Muncie jail and put me there for three days, without any charges.

I asked the turnkey (his name, even, I remember: George Brass) why they locked me up for three days without a charge, and he said they had a man in there eight months without a charge, because he kept raising hell, threatening to sue, etc., so they released him and re-arrested him as soon as he exited the jail door. A fellow inmate told me the Sheriff (I remember his name too: Fred Puckett) and his gang received $1 per meal per prisoner.

There were some 75 prisoners, so that was $225 per day for them, the meals (slop) costing perhaps as much as 10 cents each to prepare, one of their scams among others. One inmate told me, "When they release you, keep on walking without turning your head until you're out of sight, and keep your mouth shut." So I did.

Imagine my joy, about six months later, when I picked up the newspaper and saw the headlines: 63 COUNTY OFFICIALS ARRESTED AFTER STATE INVESTIGATION. This included some judges, many law-enforcement officers, the Sheriff himself, and others. Many were put in the penitentiary.

And now, an incident you may not believe, but I will swear on anything that it is 100 % true.

I had obtained a ride to California with a Mormon who had bought a car to drive home to Arizona (his name was Flake, from Snowflake, Arizona). I rode with him that far. In Ashfork I stood all day long at the main intersection, for nobody would give me a ride. That night a man in a truck, with others, told me he would give me a ride to Wickenburg, and he did.

In that town I joined others and hopped a freight train, which took us to San Bernardino. They advised that we drop off the train in the suburb of Devore, for the railroad detectives were murderous: meaning, they had killed people for riding the trains. I dropped off and walked down to Highway 66.

I went to Hollywood, walking a lot, ran out of money there, slept in a vacant lot, walked out to the Coast Highway, found a ride to Hayward, and from there to Salt Lake City.

The incident happened next. I reached Wyoming -- I think it was the town of Green River. Everyone there hated anyone who hitchhiked or rode trains, and threatened to jail us if they caught us. So we tried to keep out of sight. I became very thirsty, however, and went up to a gas station that had an outside water fountain. The attendant approached me and said, "That's for customers only." He wasn't joking. I didn't get any water.

I walked most of the 300 miles across Wyoming -- the most inhospitable place I have ever been in my life.

CALIFORNIA

Robert Wall

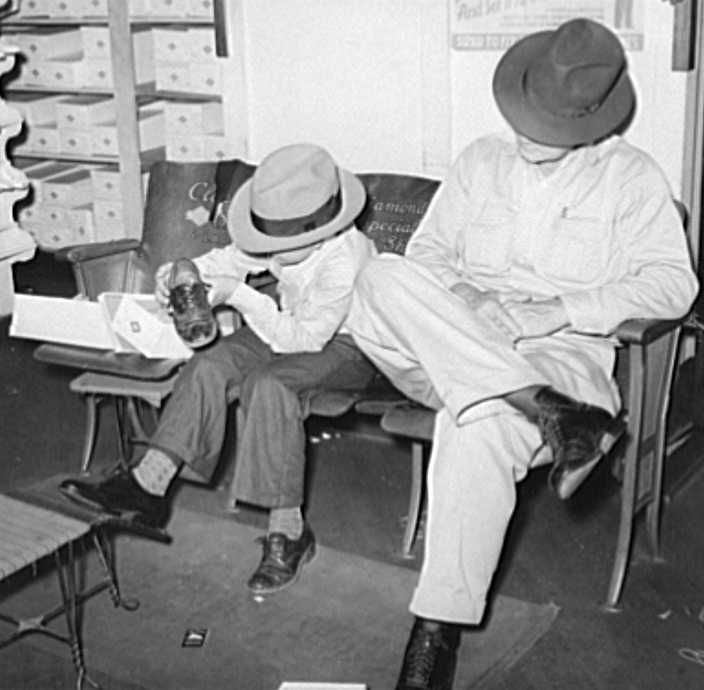

He tells of sitting in a hobo town and hearing that there was work in LA if you ride in and get caught by bulls. He rode the rails into LA, got caught and thrown into jail overnight. Was given a hot meal and a chance to shower. And was given temporary employment planting trees and shrubs in Griffith Park.

CALIFORNIA

Ross Reager

19, 1933 summer

Homesickness for my former home, St. Louis, MO. I had come to San Jose CA with my father and mother. My father was very sick and died shortly after arrival.

Memorable people I met:

The convict: He never smiled and the men shied away from him. But it was he who took my great loose bindle and put my tin “stuff box” in the middle and then roped it all up tight and made a rope sling to go over my shoulder. He said ‘One hand for you and one for the ship.’

Old Billy: He took me under his wing and I am sure saved my life. He was a WWl vet and an itinerant farm worker. He was on a WW1 pension. Had a limp.

I got locked in the ice compartment of an empty refrigerator car. I was with Old Billy and we’d climbed down inside because the cold wind on top would have frozen us stiff. Just as the train was leaving the yards, someone came along and dropped the ice compartment door. By the time we realized the import of the sounds above, we were trapped. The railroad employee who closed the doors did not drop the plug door separately from the top door. If he had the plug door would have wedged into the opening and would have been immovable from below. Because the plug hung unsealed below the upper door, I was able to stand on Billy’s shoulders and push with my shoulders and the back of my head and neck and push the door open.

As a railroad worker for 38 years, I've heard many stories of people opening ice compartment doors, and finding men dead inside.

The Lady Who Ran a Motel: I rented a room for 50c when I couldn’t get out of town. In the morning she called me to the office as I was walking out to the street. She had a huge breakfast ready for me. We talked for a long time. She took a card I had ready to mail home to Mom. She said she hoped someone would show the same kindness to her brother who was out there on the road somewhere.

It taught me that I could face the world without family or Church, or school or a community that cared if I lived or died. It helped me to learn that I could make it on my own and trust myself to take charge of my own life.

It taught me understanding of people in tough situations, who are doing whatever it takes to make it through the day. It taught me to believe that people are for the most part, good. That the bastards are the exception to the rule, no matter how hard it is to remember, because they can do so much harm. It taught me it is better to experience life than to hide from it.

When I hitchhiked I found that I was nothing to most people. Even when they gave me a ride in their car, I was like a piece of paper they picked up, read or looked at, lost interest in and dropped by the roadside. They were not hostile, they were neutral. Not being somebody in people’s eyes was a real experience.

CALIFORNIA

Roy Taylor

Jailed for vagrancy at 4 a.m. on Christmas Day, 1933 in San Diego

“That was a Christmas that I never forgot. I was thrown into a tank with 25 or 30 other guys. We had standing room only and almost starved before they released us.”

We were booked as vagrants, Roy 17, Bob Wallen, his buddy 17, and Leland Brown, "Brownie," 21.

They fingerprinted and took everything away from us, knives, razors, blades, matches etc. Brownie had three or four dollars, I’d two and Bob didn’t have a cent. We only had one sack of Bull Durham left and it was taken away from us. It didn’t matter because we had no matches anyway.

They herded about 20 of us into a very large cell. As time went on there were more brought in. I recognized some of them from the night before and I doubt if any of the hobos escaped. There was a sort of wooden platform against the walls about six inches high and an upper and lower steel spring-like bunk on one side. There was an old drunk on the top bunk that acted like he had the DTs. He was romping around and yelling and had thrown up on the bed and floor.

The smell was awful.

One guy had sneaked an orange in but when he started to peel it, the guard saw him and took it from him to avoid a fight.

About 4 a.m. some skinny wino-looking guy with a dirty white apron and cap came up to the cage and asked if we wanted some breakfast. A lot of the guys said Sure we are hungry. The old cook said, OK, give me some money. A few of the guys did including Brownie who gave him $2. Of course that was the last anyone saw of this character.

About 6 a.m. a guard came in pushing a cart with a lot of tin cups with black water and gave each of us a cup and two small slices of the most stale bread I had ever seen.

About two hours later a guard called everyone out except Bob and me and the drunk. Bob asked guard if we could go too. The guard said you two are juvies and the juvenile judge does not work on Christmas Day so you will be here until at least tomorrow.

A couple of hours later, the guard opened the gate and said come with me. I asked if we were going to be released and he said, No. He took us to a waiting police car and no one would talk to us. The car stopped in front of the city hall. We were taken to an office where a man told us he was judge so and so and had interrupted his Christmas celebration just for us. After a little sermon about the sins of being jobless and broke, he told us to be out of town by sundown or he would put us in juvenile camp.

I had never seen so-called good times in my life up to then. I just figured the times were about the same as they had always been and would be. I figured I was lucky when I got anything and really hadn’t done anything to deserve more. I was single and figured as long as I got enough work and money to get along there was no worry. I never thought about the future.