WASHINGTON

John Fawcett

Upper middle class kid with wanderlust.

Childhood remembered entirely with warmth and pleasure. My father was a doctor of ophthalmology….a surgeon for the B & O Railroad

Runaway……I was just using that as an excuse for revolting against the suffocating confines of the strictly disciplined military education system which I was growing to detest more every day…. On the evening of Feb. 7, 1936, with the temp below zero, and the ground covered with snow, I ran away from home…

Joined hundreds of thousands of transients in 1936 not because he himself was destitute but because he was what hobo scholar Drummond Mansfield has called a "scenery bum" -- a person who lives the hobos peripatetic life for the thrill and enjoyment of travel.

“The year 1936 was soon to be known as the worst of the five-year drought which decimated the farmlands of Middle America…

And so it was among these legions of homeless and poverty stricken people wandering the highways and railways and hobo camps of America that Mick and I were to travel with in June and July of 1936. And I was never to be the same again.

"I'd run away from home and spent many weeks riding the rails all over the country, living in hobo jungles, experiencing the inside of small town jails, trying to avoid starvation."

We caught the famous Cannonball on the fly. It was a hotshot manifest and the fastest freight I ever rode. A hundred miles in two hours flat.

“Down out of there bo, one false move and you’re dead.” Jailed. My first impression was the overwhelming stink of confined humanity, stale urine and oppressive heat. Kangaroo Court.

“After we got out of the jug we got some eats and then nailed a hot shot train of solid reefers, about 70 cars all iced.”

“Running the tops of a fast freight is about the quickest way to get your ass killed.”

"To beat the road" -- riding freights for a great distance

Riding tender, blinds, going through 15 tunnels... "death-dealing smokestack"

"Worked at the Southern Pacific ice house with a couple of harvest stiffs."

Unwritten conduct/ bond of sharing

Infestation of locusts causing engine wheels to slip at Wells.

Unemployed railroad workers between jobs rode the rails

"My funds are shrinking. but if all goes well I will make it to Duluth. God I hope there's work there!"

Went into the hole at Hebron. Took a sidetrack, while trains came roaring past in the opposite direction.

"It seems to me that the railroad business would be much better if there were as many passengers riding the passenger trains as there are on freight trains."

"I will never forget the night in June 1936 on the Missouri and Northern Arkansas RR up through the Ozarks, riding in a boxcar with twenty or more people including an Okie family and their little baby screaming all night with diphtheria.

Mostly migrant workers or runaways or workers of one kind or another temporarily unemployed like me roaming the country and looking for a job. And, of course, a sprinkling of old time hobos and bums who just ride the rails and live in one jungle after the other and talk about the past.

A kinship with the scores of people they saw on the trains every day sitting in the open box car doors and on the tops of the cars as they went sweeping by. The light show from firebox and headlight…bright circle of sparks surrounding the wheels scarey as hell first.

The number one basic rule of security when “beating the road” and that is safety in numbers.

“It was more than just the constant hunger. The romance of adventure was rapidly dwindling, and I didn’t like being all alone out in the country. When there were migrant camps and people on trains nearby I didn’t feel lonely or threatened, but rather I felt an excitement of being a part of some movement or something unique, and even frightening that was taking place in our country and sweeping thousands and thousands of helpless people along with it.

" I couldn’t have put it into words then, but of course what I was experiencing was the human tragedy of the Great Depression, which I’d learned practically nothing about at home."

Marshall, Ark. Poverty and despair. Discovering the real America. . .

"What fascinated me most that day was listening to their conversation. I remember being disturbed and troubled again that there were things very wrong in this country that no one ever told me about.

“Before I went to sleep that night, I remember hearing the rain on the roof and being in a quandary of despair that there was so much going on in life that I’d never learned about at home or in school."

Arkansas River between towns of Van Buren and Fort Smith, right close to the border with Oklahoma, the biggest hobo jungle I ever saw. It was more a series of camps, but must have covered several acres of ground.

Blue Bonnet to Dallas Texas Centennial Fair: 280 miles x 7 hours in blinds..

Hocked his goggles for 20 cents. Two meals and tobacco in one day, this was more damn like it.

Got home 4 July 1936...

In 1937, left home for adventure It changed my life. I became a socialist.

June, 1937, graduated from High School. Hitched from home, Wheeling, West Virginia to Baltimore, looking for job on ship (with parent's permission.)

"We sat around fire all night arguing about the war in Europe. There's lots of talk and concern now about Germany invading England this summer. I've heard it all across the country the last couple of weeks."

Went on to become a Spitfire pilot. "As a fighter pilot in the skies over Europe I was to experience the exact same mixture of fear and exhilaration when German fighters came charging down through our formation."

WASHINGTON

Kenneth Locklin

Impressed…

Just dangling my feet out the door of an empty on the Katy RR. That’s the MO Kansas and Texas from Parsons to Coffeville. I was warm in the sun shine and my belly full and the wheat looked golden and God was near by.

Saw African-Americans mistreated throughout the South. Everywhere. I learned to love those people. They were very generous with what little they had in every case I can remember. Always happy and cheerful. Being from Kansas originally, I never understood people's mistreatment of them.

WASHINGTON

Leslie Paul

1933/34

“I was only one of the tens of thousands who knew the rejection of those who may have pitied but yet feared us.

"We were mostly loners, camaraderie didn’t exist because we didn’t trust our fellow travelers.

“We hobos were all aware of never ending hunger pangs, all filthy dirty for lack of bath, mostly unshaven, traveling without destination, seeking we knew not what, sharing what little we might be able to scrounge..”

Leaving home/ catching out...

“Mother made two sandwiches for me and put them in a paper bag. She went to her purse and have me every cent she had – 72 cents. I gave her a big kiss and an extra long and tight hug. She said nothing but the tears streamed down her face.

"I turned my back and left, with the black satin bag over my shoulder. If I had been brave enough to turn around, I would have been coward enough to go back. I stopped at the roundhouse and found Gus, my stepfather, working on one of the engines. I shook his hand and said goodbye.

"The realization of dependency and loneliness immediately engulfed me. The son and stepson of railroad men, quite familiar with the workings of the railroad, was at a complete loss when it came to catching his first freight train.

“I started up the hill to the highway. I turned around at the top of the hill. The tears came, then one sob. The second one was swallowed.

" Was I leaving little for nothing? Every boy became a man, some younger, some older. I was eighteen and one week.

“Two blasts of a highball rang through the fast fading light of early evening. The unnoticed locomotive then became visible a quarter mile away as the water tank. Gray and black discs of smoke rose from the stack at intermittent intervals. The train accelerated to a faster than anticipated speed.

"I ran to the side of the train when the engine roared past. I raced alongside trying to equalize the speed, the bag in my right hand, my left hand free.

"My left hand contacted the rung of a ladder and held fast. The momentum jerked me off my feet. Suddenly it was dark and like a nightmare. I was grasping for a hold with my right hand which was still holding the bag. My foot sought the lower step and missed. I felt the turning of the wheel against my foot.

"The next second was an eternity. Why had I left home? The inside of a hospital room became a clear picture in my mind. There was a young fool kid without his legs attended by sorry doctors and nurses, living the agonies of hell. God erased the picture when from out of the dark, a strong hand grabbed me and pulled me up. I relaxed for a second on the platform at the end of a hopper car…

"My thanks were extended to my benefactor by offering him a tailor-made cigarette…

"The noise from the wheels below was deafening. The dust kicked up by the wheels in front and propelled by the undercurrents of air was anything but pleasant. The rapid vibration and bouncing of the empty car was rearranging ever single one of my body cells.

“The train stopped at McGregor. John told me he was going to ride the top, after finding no empties. This young novice followed. The night was warm even with the freeze created by the motion of the train. The moon was bright and each perceptible star was out. Then we rounded a curve, I became aware of the unbelievable number of silhouettes in a knees chest position.

“I avoided the six irregularly arranged bodies on the boxcar floor and went to the door. Two cold and shivering hands practiced rolling a cigarette before offering one to my mouth. I smoked and the taste of the wheat straw paper was good, sitting in the door with my two legs dangling was relaxing.

"The green rolling countryside dotted with farms was an ever changing picture. Like human faces, the farms were similar but no two identical.

The visual rhythm of the telegraph poles as we passed them worked a magnetic affect on my eyes. …It was perhaps the cessation of noise and vibration that again woke me….”

WASHINGTON

Norma Darragh

March 1938

18 year old riding with husband, Curly, and his nephew, Harry.

Traveling from Sioux City, the only car available was a gondola, just as long as a boxcar but its sides went up only about four feet all around the car. The upper half of the gondola was completely open to the weather. My husband said they mostly used the cars for coal etc. There was a box car just ahead of the gondola with four inches of snow on it also. We climbed into the gondola thankful that we had it to get away from Sioux City.

When the train gained momentum and was going full speed the snow from the boxcar top started whirling off onto us. It hit us just as hard as if we'd been in a blizzard. We actually felt like we were in a blizzard and there was nowhere to get away from it. We turned our backs to it and kept walking as it was bitter cold and I’m sure we'd have gotten frostbite if we hadn't.

I feel I know how the wild animals and the range cattle must feel in a blizzard! Soon all the snow had blown off the boxcar ahead and we were very thankful for that. We huddled up close to the front of the gondola staying out of the cold wind as much as possible. It is strange I don't remember much conversation going on between the three of us during these hard times. It’s as if we reserved our strength for the business at hand which was surviving.

We left Sioux City a little after noon and traveled very slowly west to a little town called Plainview. It must have been close to midnight as there was only a night-watchman at the station. It was there that we ran into two or more bums like ourselves for the first time.

They showed us into a part of the railroad station where there was a big stove that reminded me of a chicken brooder in some ways. It was used to dry and warm the sand that the rail workers put on the slick icy tracks. Also to help melt the snow from where the train slowed down to come into town. This stove had a kinda upside down ice cream cone shape. The wet sand moved down a throat like pipe drying as it moved down.

The sand came out warm and dry at the bottom in quite a large circular area on the floor. There were about three other bums sprawled on this warm sand. My husband, little Harry, and myself joined them. There we all lay like six petals on a daisy around this warm circle of sand. With a huge sigh of relief for the warmth and the soft cushion of the sand I drifted off to a much needed sleep and rest. I do not recall of once worrying about someone robbing us of our shoes, clothing, or the like.

We never had any money so that wasn't anything to worry over. The thought of being raped or murdered never crossed my mind either.

We were roused up early the next morning by the night watchman saying, "I'm sorry, but you guys have got to get out of sight because if the railroad dicks see you, he would run you all into the county jail for vagrancy."

We left our warm spots reluctantly. Shortly after we were on another flat car with tractors and farm machinery on it, heading west. It was the only thing we could get on and halfway hide ourselves until we were out of sight of the town. We didn't want to be picked up for vagrancy and thrown in jail.

This was one hell of a cold ride too. As the train got going faster and faster I hung onto one of the big tractor wheels for dear life! We didn't have much room to move around on this flat bed car and at times my legs got very cramped from the positions I had to maintain. It was quite a long ride into the next town, or so it seemed to me. Like almost forever!

I remember the train making several stops from Plainview to Shadron, Nebraska. but it was for such short time periods we were afraid to get off.

The train only stopped long enough to pick up water and fuel.

We reached Shadron, Nebraska about midnight, cold, hungry, and stiff from sleeping, or trying to sleep, on the boxcar floors.

Our next stop was at a small town called Crawford. Fort Robinson was very near there also. As we bums all piled from the boxcar we found a hobo jungle across the tracks near some trees. The hoboes had a fire going and a big stew pot over the fire, smelling good. They also had some coffee brewed and were offering it around. They offered me some in an old unsanitary looking tin can. I didn't want to refuse fine gesture from the old hobo so I took it reluctantly and thanked him.

I then took a sip of the worst coffee I've ever tasted in my life! I didn't dare spit it out so I swallowed it and prayed to god that it wouldn't make me sick. It tasted so strong it would have floated a leaky battleship if it had been an ocean. Also there was a lingering flavor of gasoline as though the can might have been used to carry gas in it some time.

The old hobo, whose camp it was, lifted the lid from his stew pot and I saw he had all kinds of vegetables floating in a greasy mess. The carrots still had their green tops on them. Those guys didn't waste anything.

They invited us to stay and have stew with them but I gave my husband the "eye" and he got my unspoken message.

We told them “thank you kindly” but that we wanted to look the town over.

So we left. I told my husband after we were on the other side of the tracks that if the stew didn't taste any better than the coffee, I couldn't have eaten it anyway.

We had a long wait for the next train to come through that small town. We decided to wait near the railroad tracks on a low bank that was facing the town and the sun which warmed us through and through. We sat there enjoying the warmth, thawing out as it were talking about the first thing we were going to do when we reached Casper.

I said, "The first thing I’m going to do is get out of these dirty clothes into a warm tub of soapy water and scrub and scrub and wash my hair."

"Me too," my nephew and my husband chimed in.

Around 11 a.m., I began to hear my stomach growling at me and the more I sat there the hungrier I got. "See those houses over there,” I said, as I pointed them out to my husband.. "I’m going over there and ask for some food. I am so hungry I can't stand it any longer".

"OK," he said, "But be careful".

Off I went, hope in my heart and my stomach growling at me. As I was trudging along the street I remembered all of the men who had come to my mother's door asking for food and she never turned them away. I was buoyed up by this memory and felt quite sure that I too would be treated the same way.

I look back now and I am amazed by the positive attitudes I maintained on this trip. Never caught cold, never got a stomach ache, not even any repercussions from the awful coffee. I picked a home that looked like a nice ordinary house such as you sometimes see a few blocks from the railroad tracks.

I went to the back door, knocked a couple of times. A lady came to the door with a child in her arms. She really looked me up and down. I realized she was thinking who is this dirty person knocking on my door. Right then I was shamefully aware of the dust and dirt on my imitation karakul fur coat, my muddy wool-lined ankle snow boots I wanted to run, but my hunger was stronger than my shame.

After what seemed hours to me, she finally asked me what I wanted. I said, "Lady, "I haven't eaten for several days and I am awfully hungry".

She looked me up and down again and said, " We have already had our breakfast and my husband won't be home for lunch for an hour or so".

My heart sank, as I realized she didn't want this dirty homeless-looking creature in her kitchen. But I am a survivor. I said, " Lady, please, I don't want to eat with you, I just thought you might be able to spare a sandwich for me".

"Oh, she said with a little more enthusiasm," How would you like a scrambled egg and bacon sandwich?"

"Oh yes," I replied, "That would be like a feast.

"This very kind lady fixed two wonderfully hot, tasty bacon and egg sandwiches for me. I thanked her with all the feeling of gratefulness that I could put in my voice without crying.

"I went back to where Curly and Harry were waiting for me. I offered my husband a sandwich and he wouldn't accept it even when I begged him to."

He said, "If I can't go for my own food I shouldn't eat yours."

No matter how Harry and I tried to change his mind he would not eat.

Little Harry and I ate those tasty sandwiches in short order! In a little while Harry said, "Aunt Norma you did so good bumming I’m going to go see what I can do."

OK, we said. Just don’t go far you might get lost.

Soon he came back with a bag of tiny sandwiches that had been left over from a bridge party the ladies of Crawford had held the day before. Well, even my husband couldn’t resist eating this time.

WASHINGTON

Oklahoma Slim

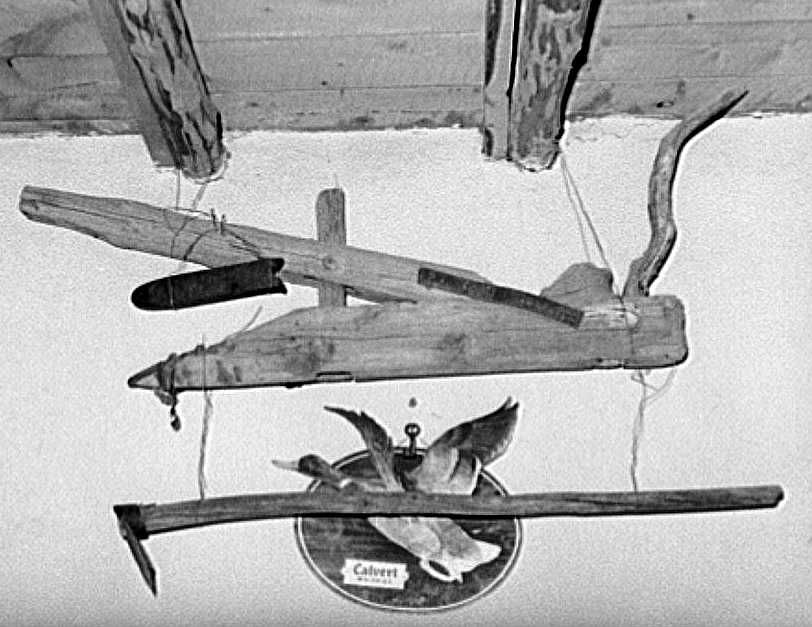

"In the beginning of this country there was a lot of single men with no home and only a few bits of clothing. The only thing they owned was a hoe. They worked the farms and when the work was done, they would tie their little bundle of clothing on their hoe and move on.

They called them "Hoe Boys," later that was shortened to "Hobo." The word bundle was changed to bindle and stiff was added. Every upheaval in this country puts men on the bum, makes entire families homeless. The Civil War made thousands homeless, most finally made it back. The Dirty Thirties put millions on the road, there was two million riding the freights alone……

Mostly I rode the freights. I watched as armed men rounded up freight train people and loaded them in cattle cars going east. 50 or hundred at a time. I ran the blockade several times just to show I could.

WASHINGTON

Peggy De Hart

15 in 1938

Lived on ranch at Glendo, near the eastern border of Wyoming

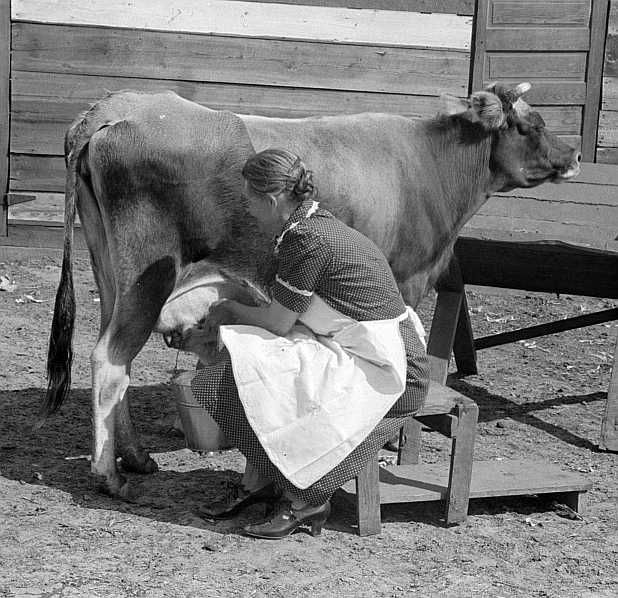

“I can blame it all on a cow. It was July 1938, I was helping my Dad milk 13 head of cows. I hitched my one-legged milk stool a little closer to the flank of my cow, tucked the milk bucket between my knees and began to milk.

I watched the American Legion wearing little blue hats and carrying clubs come into the jungle and beat the hell out of the commies. For many years I thought a homeless person was a Commie."

Some demon inspired fly bit where it shouldn’t have and old Diamond switched her dirty tail and hit me square in the eye. Incensed, I jumped up with the stool in my hand and whopped her one across the back, adding a few unmentionable words.

Like a flash Dad came across that barn aisle, boxing me up one side and down the other. “Don’t you ever talk like that again,“ he said. “I’ll leave,” I yelled. “You’ll be back for supper,” he said. I wasn’t.

"Left with my friend Irene, 17.

"There they turned left to go to Laramie and we turned to go west. As we turned toward Bosler, two cowboys on saddle broncos came by and offered us a ride into town. Up we went behind the saddle of each rider and up the road we went on two horses trying to buck.

"Nobody would pick us up at Cokesville, Wyoming. The white slavery law made it a crime to transport a woman across a state line. So we switched to trains."

"The train came into water and we all climbed into an open boxcar that had been used to haul wheat. Soon all four of us were sitting in the box car door watching the country go by. I quickly learned not to swing my legs.

Slim (Jack Fuller from Casper, Wyoming, age 37,] sharply slapped my shins and warned me not to do that because a railroad switch could jerk you off the train into eternity.

5 weeks x 2,400 miles.

I certainly looked like a boy. I was a stick 90 lbs.

"I witnessed the corrupt regime of the Roosevelt New Deal as they robbed ranchers and farmers."

"Went to serve as a missionary in Trinidad when I retired at 66."

WASHINGTON

Peter Chelemedos

Summer of 1937, after many fights with my older brother, I left my home in the Bay area of California to hit the road. I was 15.

Walking down that highway on a hot afternoon, I reached across the barbed wire fence to pluck cotton bolls to chew on for what nourishment was in the cottonseed oil. Talk about hungry!

I hadn’t eaten since I left Tucson the week before, and was hungry and listless. My companion noticed it and asked me why I didn’t hit up a house for something to eat. I told him I couldn’t do that as I was supposed to be independent. I couldn’t admit how bashful I was and didn’t have the nerve. He told me I shouldn’t let my independence interfere with my health.

Since it was about supper time, he told me to walk up the street on one side watching into the houses, and he would walk the other side. When I saw a family eating dinner I was to call him. When I did see a couple eating and called him, he told me to sit by the light pole and watch, When they finished, chances were that the man would take his newspaper to the front porch while the woman would clear the table. When she did, I was to knock at the back door and tell her I hadn't eaten in over a week and ask her if she had anything left over from their supper.

I did as he advised. When I told my story, the woman looked at me and told me to go around to the front porch. Her husband was settling down with the newspaper into the rocker when I came up the steps. He asked me what I wanted, and I told him his wife was getting me something to eat. She brought out a washbowl sized dish of rice and beef stew, a loaf of French bread, and a dipper of water. To this day I can remember watching the sun set over Lafayette, Louisiana as I ate my way through this banquet.

What I couldn't eat at the time, was wrapped in newspaper and I rode on to Gretna, Louisiana that night with the warmth of this package close to me. Around midnight I started to unwrap it to eat more, but the grease from the stew had soaked into the newspaper. I tore off the dry paper and ate the rest, newspaper and all. . .

By the time I reached Ontario, California, my shoes had given out. They fell apart above the soles, and nearly tripped me up when I tried to hop a freight out of Bakersfield, it took all my strength to pull myself up on the car when I missed my footing. Not saying that shoes had not been offered me along the way, the railroad men all seemed to wear sizes seven, eight, or nine and none of these would fit my size elevens.

I had no recourse but to ask for a pair from the Salvation Army. The woman at the Salvation Army office called up a number of people and finally after much banter gave me a pair to try on. I did but the pair she gave me were old and sun rotted, and fell apart as I put them on. She refused to give me another pair since I had received my 'allotment'.

Oh, well, I spent the night at a mission there and got supper and breakfast, and a bath. I then went back up the tracks a mile or so and camped under the railroad bridge there in a dry creek bed. I scrounged some walnuts from the trees near the tracks and ate grapes from a nearby vineyard. Another hobo and myself gathered some black-eyed peas from the platform of a warehouse where they had been unloaded. . .

I was wearing only jeans and a light shirt, having been acclimated to the weather in Southern California. I rode out that night on the Western Pacific freight, which was routed up the Feather River canyon in the Sierra Nevada mountains. It had been snowing, and I was riding on the walkway outside a rail-tank car. There was no place to get out of the wind. When the train finally stopped at a water tower, I got off and walked around a bit to try to warm up. I didn't realize the snow clung to the bottoms of my shoes and later that night while riding my feet became extremely cold. When I jumped off the car next time, I could barely feel the ground under my feet.

Somewhere along the line one of the railroad men gave me a sleeveless sweater which helped somewhat since I had no jacket, and I made a point of finding box cars in which I could ride inside out of the wind for the long trip over the Rockies and the prairie states. I was still cold.

Christmas Eve, 1938, the freight train I was riding from California to New York stopped in the Burlington yards at Silvis, Illinois for its usual maintenance and switching. I was sitting in a box car shivering. I heard the footsteps of a 'car-knocker', railroad parlance for the man who checks the wheel bearings of the cars for hot wheel bearings, making his way along the snowy right of way. When he passed the car I was in, I asked him what time the train was to leave for Chicago.

He looked at me, and took in the shivering boy there without coat or jacket, and told me it would be a couple of hours yet. He told me to go down to the head end of the train to the switchmen's shanty there and warm up by the pot bellied stove. "If anyone says anything, tell him 'John sent you to wait for him there'."

Later on, John came into the shanty and shared his lunch with me.

He suggested: "Since it Is such a cold night coming up and there is a blizzard in Chicago tonight, you would be wise to stay overnight at Silvis." Since I had no money, he sent me over to the police station to have the desk man let me sleep in the jail overnight. A hard bed, but softer than the box car floor, with a blanket and warmth was pure luxury.

The next morning, after a big bowl of oatmeal breakfast, I was walking back to the freight yards again. I saw some children sledding down the hill on sleds. Since I was raised without snow, this was my first experience with actually watching this sport. I watched for a while, until a mother called her children in for lunch. I turned to go, but one of them came back and said her mother wanted me to come in too.

While I was eating my way through a bowl of hot chicken soup, their father came down stairs to join us. He was John, the man I met at the railroad yard the day before. The family invited me to stay with them for Christmas dinner.

I left the next day, on the freight for Chicago. I got off at Blue Island, Illinois and walked through eight inch deep snow along the railroad tracks to Hammond, Indiana. I caught a Nickel Plate freight train for Buffalo and New York City. I remember that ride, basking in the warm glow that was in my heart from knowing that family.

WASHINGTON

Robert Logan

16 -20, 1935 to 1939

My parents were unable to support me.

My first experience was in Nebraska on a hot, dusty day. I had just left my home in Douglas, Wyoming and was on a long freight train. In those days there were more people riding freight trains than passenger trains, it seemed. I was on a flat car with about a dozen men. The train was going slow, but to fast to hop off.

I was hot and thirsty and asked a man if he knew where I could get some water. He told me to go ask the engineer, he would give me some water. I, being naive, scrambled over boxcars, through gondolas and across flat cars until I reached the coal car. I came sliding down the pile of coal and into the cab of the engine.

The startled fireman shouted “What the hell do you think you are doing?”

I told him I was thirsty and wanted a drink. He grabbed me and threw me off the train. I had some bumps and bruises but the thing I remember most about the incident was what a long, hot walk it was to the next town.

In Chehalis, WA, I applied for a job at the bus depot as a fry cook. They had one opening to replace a cook who was going to be on vacation for two weeks. I was told they would hire me but I had to join the union. I hurried to the union hall to join.

There I was told I could only join if I had a job. When I said I had a job, the man asked where it was. I told him and his reply was, “ we have members out of work. We’ll send one over there. Thanks.”

WASHINGTON

Stanley Cole

It’s the winter of 1938 and I am in the yards at Chicago…

Jumps into a boxcar…

Then the train gathered speed and I became aware of a rapid, rhythmic clicking and a sharp vibration running through the car. This old box has had the air applied an drug a bogie, there are flat spots on her wheels. When moving over 40 mph those flat spots come around fast and set up a pounding vibration that, after riding a ways, you fear will drive you mad. You can walk, stand, lay down, sit or hang from the ceiling, if there is something to grab hold of, but you can’t escape.

I do not know how many miles I rode that night, but every mile was written on my hide. I tried every position for the human frame, and some not yet discovered. It only gave that box car one more place to pound.

WASHINGTON

Victor Cox

We met a family in Crowley LA by the name of Tew. We had separated looking for a meal. My buddy had knocked on their door and asked for work for a meal.

She said in all her born days we were the first to ask to work for food, so she asked us to stay with them for several days. We did odd jobs and it was just like being at home.

They were an average middle class family. They had a black maid who worked 10 hours a day for $2.50 a week. She did everything. Cooking. Washing in a big kettle in yard over an open fire.

Mr. Tew owned a machine shop with a large oak tree in front. He said any time there was a rape in town, the next morning blacks were hung from that tree.

We were from a small town in northwest Washington. We had three black families in town who worked in paper and lumber mills along with whites and were treated the same.

WASHINGTON

Weaver Dial

After listening to my older brother, who had rode the side-door Pullman’s up and down the coast, it seemed only natural that the time had come to be liberated and get in on some of the action of the road.

“Getting my parents approval to make these railroad tours took some convincing on my part. Since my physical health was in question, as I was an asthmatic and often had great difficulty breathing…”

“This is the main line that goes south,” he pointed out, “and when the guy in the tower there throws the switch, the big engine will be coming out of the yard.”

Around 11 p.m. we heard the hi-ball, and as the engine made the curve, it looked for all the world as big as a house. It was the year 1929 and I was 12 years old, my companion was all of 14, but we were ready and eager as we searched for an empty car.

“The hobo jungle was a great source of information. Not only in the arts of outdoor cookery, but in matters of how to gather the ingredients for the Mulligan stew, without paying for the groceries. The assembled travelers who shared their tobacco and food were also an assortment of road intellectuals, who were very believable, especially the out of work railroad men in their bib overalls, and that big railroad pocket watch dangling from a chain. They were the most reliable on the train departures, and could give all who would listen the most appropriate time schedules.

“jungle professors and philosophers”

Tunnel ride in Cascade mountains: “By the time we got our bandannas over our noses, we needed no flashlight to tell us that hot cinders from the coals were setting our clothes on fire. Emmy and I were busy extinguishing the hot embers and sweating something fierce up there on top of the woodpile, about as close as we could get to the roof of the tunnel. Let me tell you,, it was a long two mile ride! When we finally pulled out of the black hole, our faces were grimy and black, but we were in fresh mountain air, and life looked better. After the helper disconnected we were on our way down the east side of the Cascades.”

In 1930 when I was 13, trips to Yakima, 150 miles from Seattle were commonplace. It was in the hobo jungles of Yakima that I witnessed a fight that is still vivid in my memory. There was much drinking of denatured alcohol in the railroad jungles, not only in Yakima, but everywhere I went. Men out of work were so despondent and discouraged at the state of their future, that they would drink almost anything to ease the pain.

We were out to see America and what we could get out of it. As we approached the mid-thirties, the hobo jungles were more populated.

Some months, the $20 (father’s Spanish-American war pension) was all the cash that came into the house, in spite of the fact that we kids sold sweet peas and box wood to neighborhood ladies who couldn’t resist a bargain. Times were tough in the household, but they were rougher in the hobo jungles. It was a lesson they never taught us in school.

It was common knowledge in all jungles that bulls were to keep unemployed men on the move.

“A small town in Nebraska. They rounded us all up at gunpoint and herded us into a small railroad station. We were all lined up and told to take off all our clothes. As one stood guard, the other two meticulously went through our pockets, the brims of our caps, even detailing our shoes and fingering our belts.

They made the rules: “You can’t ride the Union Pacific without paying. Now all of you with money will be allowed to keep one half of your possession, the rest will go to pay your fare.”

Four bucks was my entire bankroll, so I was given a $2 ticket on the first passenger train that stopped. “The rest of you have no choice, you’re going to jail.”

A hard working bindlestiff, who had been working the harvest had $80 on him, which he had planned on taking home to his family. His carfare was $40 which they sacked. It was a heartless thing to do, there was no affection or feelings for his labor whatsoever. My feelings for railroad bulls were never lower.

Up in northern California along the Keddi River was a branch line that ran east to Utah. The Southern Pacific stopped in this desolate mountain retreat. Just below the tracks, and above the river, was a bean house. A former out of work hobo had built a shack against the bank and opened up his beanery. For all of one thin dime,, you could get a pie tin full of hot beans, a stack of bread and coffee. Even ketchup. Here was a flourishing business, built on dimes.

There were times when he would have to leave some bo in charge while he rode the rails into town for supplies. There were no state licenses on the wall, no building inspectors, no sanitation, just good hot beans. On our trips to California from Seattle, this stop was high on the list to fortify one’s body for what lay ahead. To this day, I never eat beans that I don’t think of that nourishing pile of goo on an old pie plate…

There are some things that you can’t buy a ticket to.”

WASHINGTON

William Creed

17 and 18, 1934-1935

“To alleviate burden on family and seek employment to help at home.”

In Salinas CA, we went to back door of a fairly nice looking house, knocked and asked if we could work for food. A middle-aged woman told us to wash up at an outside faucet, then took us in her kitchen and fed us fried chicken, potatoes and gravy and apple pie. We then did some odd jobs for her and she gave us each a dollar and sent us on our way, wishing us good luck. I will never forget that woman.

When we rode through Tehatchape Mountains in California, we were close to the front of the train. We would go around hairpin turns and could look across deep canyons and see the caboose straight across from us on other side of canyon.

My buddy and I got in a boxcar and there were two men already in the car. They gave us a candy bar each and were patting us and calling us honey. We heard enough talk to figure what was going on and so when the train started moving we grabbed our packs and jumped out.

WISCONSIN

Al “Squibby” Henrich

My boxcar days started in 1914 after we volunteered for a government job in Stetton, Kentucky -- 60 boys were sent there as mule skinners.

In this army camp we did not get to drive mule teams, but were put to digging sewer ditches. I was the only one to drive a team once, and then was put in charge of inspecting the depth of ditches the boys were digging.

Well that first day all these other fellows came to barracks and bunks and confined to me they were quitting next morning. The guards came and threw all out, clothes or no clothes.

From there we all drifted apart and a buddy and I hitched a train out and rode the rails to wherever.

At Jefferson, he had me ask for shelter at police station and an officer named Mr Peck asked where we were from etc. He gave my friend Ed Hoffe and I a hotel room for one night. In morning we tried to hitch train ride across the Ohio river getting one finally and half way across the bridge we were arrested and taken to jail.

We were sentenced by prisoners to 50 lashes for "breaking into their jail" without their consent. Well we both got our 50 lashes across the butt with a socked belt. You took it, there was no way out. Lots of things happened in my stay for a week. I landed up with 90 lashes. Each prisoner had to hit hard or they called contempt of court…

I bummed the harvest fields in Mitchell, SD. There were many times friends would just say let’s hitch a ride and we landed up many places. I got a job on a section gang and got to be cook's helper. Ate my first good raisin pie there, and then on my way again. I often wonder about the good folks of those days. There were many things, and not any of them to be ashamed of.

I had sixty-five jobs before I got married in 1925 and did lose my wife after 60 years married. In July 1992, I got married to a wonderful gal, Virginia. We are great pals and its never too late to say "I love you," and mean it. It's a great life!

WISCONSIN

Dorothy Gavin

I was a waitress in Oshkosh, WA. 1937.

One Wednesday night there were two young women in a booth. As I took their order a solitary youth came in. He was dressed in jeans and a khaki jacket. He wore a droopy hat. He sat at the counter looking at a stale breakfast roll in its glass case. I asked what he would like.

“How much is that roll?” he asked.

“Ten cents,” I said.

He looked thoughtfully at it. “How much for a cup of coffee?”

“Five cents,” I said.

He sighed and set a dime down on the counter. “I’ll take that roll and a glass of water please.”

I knew he had only a dime, so I said, “I guess we could sell that roll for a nickel. It’s been here getting stale.” I served him and went over to the two young women who were beckoning me.

“What is that boy having?” and “Give me his check.” They both spoke at once. I told them and gave the boy back his dime. Then, summoned by the night cook who had been watching through the window in the kitchen door, I went to the kitchen and told the story. He said, “Send him back here. So I did.

The boy in a mystified manner went to the kitchen, where the cook dished up meat and potatoes, buttered corn bread, butter and milk. He rounded it off with a slice of pie.

They gave him a chair in an out of the way corner. He was stuffing himself when our proprietor came out, and having been told the circumstances, directed the boy to go to the old post office which was right across the alley and ask for accommodation. – The government had recently given our city permission to use the building as a shelter for transients.

That is all I know about the story. I thought it showed such kindness, charity and good feeling. What neighborliness had been shown that night.

Surely those who had done their mite had little to give, but gave it freely, not waiting to be asked. And the young man had shown dignity, had not begged, nor applied for sympathy. He had said little beyond “thanks.”

This sort of thing happened often during the Depression because we all thought “That could be me,” when we saw the plights of our fellowmen. And I thought of the mothers and brothers of boys like that, and how they were probably worrying too.

On the other hand there were those knights who took to the road professionally.

About a year later I was still only employed part time. My parents house stood near the Northwestern depot. At about supper-time one spring evening a shabby fiftyish looking man came to our door and asked for something to eat. I let him in. Dad was at home or I wouldn’t have.

Mother put the remains of our supper before him and he ate. He was dingy looking. He had two pockets in his vest tied with shoestrings. When he took off his coat to tuck in I saw a straight edge razor in the inside coat pocket. His other clothes looked ragged and he needed a haircut. His face was red.

He emptied two pots of coffee and jokingly told me to keep it coming. “You’ll have to be faster than that to catch a husband,” he said.

We became a little nervous. Mother and I withdrew to the living room. My father stayed at the table with our burly, talkative guest. Dad liked to talk too. To tell yarns. They were soon swapping stories. All the food on hand was eaten. Once a kitchen chair scraped suddenly on the floor, and Mother and I were all set to run to Dad’s assistance. We walked, instead, as being the best policy, and found that it had merely been Dad going into the next room to get his razor to show off.

The stranger moved to go and asked if we had a cigarette. I gave him a package of mine. He left and we never saw him again. We rather feared our house would be marked by bums, and we would have a rash of hungry visitors, but that never happened.

WISCONSIN

Herb Jorsch

1938

17 - 19 year olds, out of high school, helped friend's family work sugar beet harvest for food, for three weeks. (Given five silver dollars bonus).

Headed home:

“Arriving in the Minneapolis freight yards cold, wet and wondering how to find our way home, some railroad brakemen found us. They took us into their locker area, helped us dry our clothes, gave us what they had left from their lunch, told us to avoid getting near the windows where the bulls might see us and later that night took us out into the yard and put us on a fast freight headed for Milwaukee. What wonderful caring people."

WISCONSIN

Ina Maki

Graduated from Virginia MN high school in 1939, beginning of Depression. I knew it would be a grind to work myself through Duluth Teachers College so I decided to see the USA that summer.

My friends, the boys, were all riding boxcars. My father had ridden the rails to the Dakotas for the wheat harvest. I told him I wanted to ride the boxcars somewhere west.

Father was always supportive of my projects. He said. “It will be dangerous. Here’s ten bucks.”

Waiting by the railroad yards in Duluth, I was approached by a young man, maybe 25. He said “You’re planning to ride the boxcars. I’d better go with you.”

I’d spent my ten bucks on an awful permanent wave, which I covered with a bandanna. So my self-appointed protector called me Curly. Never anything else.

He never told me his name. But told me he was from Gary, IND. We journeyed by boxcar or oil tanker to Denver. We even panned gold in Cripple Creek near the US mint. We got sunburned. I had to get back to MN for school.

In Duluth, this guy said, "Happy landings, Curly." Didn’t even shake hands. Never once touched me. He was a hobo, not a bum. A gentleman.

WISCONSIN

Joseph Watters

Rode 1931 to 1929

Adventure. From age 15 to 22

One of the most lasting and impressive sights that I saw took place while crossing the Ohio River near the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers at Cairo, Illinois.

I was standing near the door of a boxcar at the rear of a freight train, crossing into Kentucky from Illinois. As the train approached the high bridge over the Ohio on a long curve, I could see the entire train from the rear to the front.

I had seen hundreds of hoboes on the rails, but I had never seen so many on one train. Literally hundreds of men were in the cars, and clinging to the tops of the boxcars, and brought home to me how vast was the number of men aimlessly wandering around looking for work. It was a sobering thought and observation, even for a 16-year-old.

WISCONSIN

Quintin Hartjes

“I am writing my true story of one fact of my life I am not proud of. Now at the age of 78 when I think back of how I hurt the good parents I had by running away from home and the rough times I had as a consequence, the memories still haunt me.”

I made contact with my parents at home to let them know I was still alive, and when I came home almost six months later, they welcomed me with open arms. I guess they thought they would never see me again. I will always regret my running away and the grief I caused my parents

WISCONSIN

R.A. Ursic

Fran Peters and I had just finished high school in the Great Depression years. With 24 per cent unemployed, our job prospects were slight. We were big enough to take care of ourselves and felt we could not continue to be a burden at home. So we decided to go to South America.

My aunt had a friend who had a small hotel in Rio de Janeiro. The plan was to ride the rails on the northern route to Seattle and then catch a boat to our destination.

Thus one summer night we found ourselves on a freight train out of Milwaukee bound for St. Paul Minnesota.

“We hitched out of Fremont, Nebraska to the next town where we saw a long freight train headed west on a siding. It was scheduled to leave about eight or nine that evening. In the twilight of a warm sultry night we waited outside of town and selected an open gondola. The cars were moving along and gaining momentum. We grabbed the runs and swung aboard.

We weren’t alone. There were several others sitting on the sides of the car. We each found a spot and hunkered down. No one spoke. Some had their heads down on their hands and never looked up. Others tried to read us with furtive eyes. I took a closer look at the one a few feet from me.

He could not have been more than 10 or 12 years old. He was a rough looking kid with a shaggy head of hair and mistrusting look in his eye and a mouth that hadn’t smiled in a long time.

I saw him watching me. I said, “Hi, where are you headed?”

He wouldn’t answer. The train slowed down near Columbus. Some of us got off.

The kid stayed on. The harried look in that boy’s eye stayed with me a long time. At that age you’re not too well-equipped to survive on your own – even in good times.

“You had to be wary and on guard. The mark of time and desperation could be seen on the faces of most knights of the road in those days.

You become a philosopher at an early age when the sheltered life of boyhood suddenly changes to the grim necessities of daily survival on your own far from home. Personal adversity and a sense of adventure is all you need to set your sights on greener pastures in a far off land.