VIRGINIA

Betty Glover

We lived in a coal mining camp in Hartwell, McDowell County, West Virginia atop a "cut" - which meant, that our house was on top of the debris thrown up and out when the railroad was put through the hillside.

We could go "out on the hill" and look down at the trains passing. The terrain was slanted (contour nowadays) landscape down to the tracks but facing us was a steep, straight down cut. The "store manager" and "coal mine official" lived on this imposing hill. On our side, (the wrong side of the tracks you might call it) was two railroad workers houses, ours and my Daddy's boss. Of course their house was bigger than ours - we had three rooms, (for eventually 7 people), and carried water from a hand pump located in Jim and Lou’s yard next door.

I was born in 1933, during the Depression I've been told, but we never suffered a thing. My Daddy had a steady job, and my mother was off a farm and kept a cow, raised a hog every year, probably had chickens for eggs, and meat, and she and Daddy had a big vegetable garden on down the opposite hillside behind our house towards the creek.

"Hobo" is what they were called there. The folks who came through on the trains. I have one memory of a "hobo" standing outside the screen door, and Mother handing food out the door to him.

I don't believe she ever denied any of them something to eat; a hunk of corn bread or something.

I do recall that she got real mad once. Seems she had left clothes hanging out on the line out on the hill, and some of Daddy's long-johns (underwear) and other clothing (something of hers) disappeared, and also something (perhaps bacon) out of the smoke house. I remember she was real mad! Said she wasn't going to give out any more food but I am sure she did not hold to that.

VIRGINIA

Don Kite

I was married June 9th. I930. At the beginning of the Depression. Conditions kept getting worse so in April 1933, I left my wife and two-year old-son with her parents in Kansas City, Mo. and bummed my way to California by freight trains.

I rode from K.C. to Omaha Nebraska on the Mo Pac; from Omaha to Cheyenne Wyo. on the Union Pacific.

I was on the outskirts of Cheyanne, Wyo. Tried to continue west on the Union Pac. However outside of Cheyanne there is a long grade. The train was stopped and the R.R. bulls swept all of the hoboes off of the train and held us at gun point until the train left. They told us if we stayed in Cheyenne the rest of our life, we would not be able to ride the Union Pacific west out of Cheyenne.

So I hooked a ride on the Mo Pacific to Denver Colo. At Denver I caught the Denver & Rio Grande Western. In fact the railroad bulls at Denver helped me get in an empty boxcar at a rail crossing in downtown Denver.

I rode the D & R G W to Sacramento. As the train pulled in to Sacramento, a man walked the full length of train on the roof of box cars with a megaphone telling all the hobos to be sure and stop at Benny's beanery.

Sure enough, right off of railroad property, a tent was set up where you get coffee chili and soup. In front of the tent was a bulletin board listing time of arrival and departure of all the freight trains in and out of Sacramento.

At this point, I caught the Southern Pacific to Los Angeles. I got off the train before we arrived in the freight yards in Los Angeles so that I would not end up in jail.

I was a high school drop out. However I went to work for Rheem Mfg. Co. and made it to the so-called ivory tower. I had an office on the twenty-first floor of the General Electric Building on Lexington Ave in New York. I retired in 1971 after thirty-one years. I lost my lovely wife from a stroke after a very happy marriage of 57 years and 7 months.

VIRGINIA

Harold Spark

19, summer 1934

Oregon lumber company he worked for went bankrupt and so he took to rails to get home to family in Toledo, OH.

"I ran out of money in Milwaukee and did not eat for three days except for a large onion that I took from a box car and which I was taking home to show as it was the biggest onion I had ever seen, but hunger prevailed.

In Chico a day or so later I was sitting under a bridge and was so hungry that I took my prize onion and sat down to eat it. I looked up and a Yard Bull was standing over me with his club.

He asked what are you doing? I said. "Eating an onion." With that he hit me across the feet and once again I had to run for the weeds.

The ride up the Columbia River gorge was spectacular from the top of a boxcar. No scenic train ever had a better view. When we arrived in Bonneville, we pulled into a siding overlooking the dam.

President Roosevelt was dedicating the dam and I had ringside seats.

I arrived home. I had to walk the last 15 miles from Wasseon, Ohio on the Nickel Plate line and was so dirty I could not hitch hike. When I arrived home in Toledo just for fun I went to the back door of our house.

The maid didn’t recognize me.

I asked “Could you give a hungry man something to eat?”

The maid slammed the door in my face, but just at that moment my mother walked into the kitchen.

She told the maid to feed me. I asked for milk, eggs, bacon, toast. While eating my mother looked in several times.

Finally I could no longer stand it and started to laugh. My mother then recognized me and fainted dead away. My sisters rushed in and drew away as I smelled so bad.

James Pearson

Runaway at 13+ Hateful stepfather. “He raised so much hell I made up my mind to leave."

Lived eight miles from town in North Carolina.

“My stepdad was caught bootlegging white lightning whisky and was put on the chain gang for two months. We had no income at all. In the Depression it was awful.”

Mama, me and his four kids were really hungry so I went to the welfare department and they plain told me they did not feed bootleggers' families.

I told them I would work for it. I must have been convincing because they gave me a work card to work two days a week.”

No cash. Just a slip for food, so I walked four and a half miles to work. I worked nine hours for ten cents and hour and walked four and a half miles home.

We managed on $1.80 a week. The $1.80 was for that amount of food at the A & P store. Besides the $1.80 food credit each worker got a 24 pound bag of flour free ofcharge from the government.

When my stepdad was released he acted like nothing had happened and started our fuss all over again.

This time I hugged my mom and told her I couldn’t put up with it anymore and that I’d keep in touch with her. I didn’t really want to leave but I felt I had to. I could hear the mournful sound of the whistle of the distant freight train. I was on my way to California.”

Fort Worth, TX creek… 150 hoboes in the buff were splashing in the water.

Boy that looked like fun so I shucked my clothes band took my place in line for the rope. It was fun until I turned loose of the rope and found there was no bottom to the pond. I hollered "Help Help!" And a couple of hobos grabbed me and got me ashore.

"You SOB, can’t you swim?"

I said No.

Met a Bonus Vet and his 9-year-old son on their way to Washington. His Mexican wife had died and he was on his way to Winston Salem, where he had a brother who worked for R.J. Reynolds. He had a bundle that weighed about 60 pounds.

One day the train stopped and he and son went to well about 50 yards from the tracks to get a drink. The train started real fast and he and his son could not catch it and as the train was rounding a curve they would not see me throw the bundle from the train.

I had a feeling everything he owned in the world was in that bundle so I lugged it from Texas to Winston Salem where I found his brother and told him what happened. I had traveled about 75 miles beyond where I was to get off at Newton NC. I went into a small restaurant near the tobacco plant and asked for something to eat.

The couple that owned café was real nice and as I ate explained why I was in Winston. Took me home that night. I had a shower and she washed my clothes. The next morning I looked like a new man.

In Memphis, Tennessee, we got the surprise of our life. A beautiful woman in a see-through gown with garter belts, hose and high heels answered the door. When we asked her if we could work for something to eat she said sure. Her cinder driveway had a low spot and sometimes when she went to her car her shoes got wet. Could we do something?

We told her we could if we had some tools and she said we’d find them in the garage. We went into the garage and there sat a new Cadillac a mile long. We made a project of the driveway and after a while she called and asked if we were ready to eat. We put up the tools and ate in the kitchen.

Man what a meal. We also got a floor show. There was a steady stream of beautiful women dressed for action and men coming and going from the front door. It was a sight to remember.

I found the heel of a loaf of bread in the corner of the boxcar. It tasked like cake.

El Paso transient camp:

“When I checked into the camp they asked me how much schooling I had had and I told them the ninth grade. I was put to work in the office checking and keeping track of the other hobos. I made two dollars a week and stayed six weeks. I saved ten dollars and was rich. I spent two dollars for Golden Grain smoking tobacco to roll your own cigarettes. Two cents was for a street car ride across the Rio Grande to Juarez, Mexico.

The camp had smokers (theatrical plays) once a week with hobos doing the acting. They also had a boxing ring. I decided I’d try boxing so I signed up the night of the fight. They taped my hands and put on boxing gloves the size of pillows.

I was fighting at 135 pounds and the guy I was fighting weighed the same. The bell rang and we met in the center of the ring, feeling each other out.

He rushed me against the ropes and I guess he thought he had me but I brought one against his chin and sent him across the ring. He sat down flat with his back against the bottom rope, out like a light. When the ref raised my hand I knew I would be the next champ.

Well, this was a short-lived fantasy as the next week I tried it again and a farm boy hit me with everything but the wagon tongue. I said, Oh well, that’s one and one.

I fought the following week and I never saw a guy move so fast in my life. I couldn’t get a glove on him. He didn’t hurt me but kept his fist in my face the whole fight. It was then I realized I was a lover, not a fighter.

We were really broke when we got to California. We spent our last 25c for a can of pork and beans and a loaf of bread. That’s all we had to eat between El Paso and Los Angeles.

When we pulled into the yards in Los Angeles, there was a carload of rr detectives to greet us. You never saw so much running and dodging and hiding.

One morning around 3 a.m. we pulled into a freight yard somewhere in Texas. It was colder than hell as we dropped of the train as it slowed going into the yard. One of the bos asked me what I was going to do until day light and I told him I was going to find an empty boxcar on a siding and sleep until I could get something to eat. He said, "that's a good idea. I'll go with you." He was about thirty years old, six two and weighed about two ten.

We found the ideal boxcar that hadn't been moved in a long time. It was in a remote part of the yard and we slid the door open and crawled in. It was really dark inside and as soon as we were in he said he wanted to assault me. He scared the living hell out of me but I kept my cool. I told him I had to pee and when I got to the door, (Hobo's most always peed out the doors.) I shoved it open and hit the ground running.

I knew the big bastard couldn't catch me for back then I could really move. I didn't stop running until I was in the middle of town and close to a diner that stayed open all night. I stayed in town three days to give him time to move on and I was still scared when I went back to the freight yard to catch out.

One day it was pretty and warm and I was starved so I walked up a driveway and knocked on a back door. When the lady came to the door I asked for work to get something to eat. She said she didn't feed tramps and I said, "Lady, I'm not a tramp. I am a hobo."

"What the hell is the difference?" she asked.

"Well," I told her, "A tramp won't work and a hobo will."

"Well, I don't feed hobos either," she said, and slammed the door.

I thanked her for her time and walked across the driveway. The back doors faced each other. I knocked on the other door and a lady came to the door and I asked her what I had asked the other lady. She said she didn't have any work but I looked hungry, so have a seat on the steps. I did and in a few minutes she had a nice plate of food and a big glass of iced tea for me.

I was really enjoying the food when the grouch next door stuck her head out the screen door and asked if I could eat some mashed potatoes. I said, "Yea mam."

Here she comes with a nice plate of food. I guess she was ashamed of the way she had acted but I left that driveway full as a tick and happy as a lark.

Hungry in Lordsburg x all night café cook who loaned him his bed and gave him a pancake breakfast.

“Mom I’m coming home. Not because I have to but because I want to. - Love Jim.”

VIRGINIA

John C Lint

May 1927, starting from Denver Co

Three of us, 14, 15 and 17 had been riding a freight train all night and got off a stop in Cottondale, Florida, just to walk along a train and get warm. A plainclothes law enforcement officer took us into custody and in his pick-up took us to Marianna where the judge gave us 60 days on the county farm.

The warden gave us $4 when we were discharged and the warden’s son offered us a ride to Marianna for $4. The ride was declined.

The law officer that picked us up told us that he got $8 a head for all that he brought in. I must say that I saw several miles of road built.

VIRGINIA

Otto Whittaker

"The Boy Who Killed The Railroad Bull."

On a summer night in the 1930s, at the edge of the little town of Brookfield, Mo., a 15-year-old boy from Bluefield, W.Va., scooted out of the bushes alongside the track of the Chicago, Burlington 8z Quincy Railroad and grabbed the ladder on a boxcar in a freight that was just pulling out.

At the top of the ladder he took a careful look fore and aft, then crawled over to the catwalk and began a wobbly run toward the head end. He wanted to get as close as he could to one of the empty boxcars up ahead, the empty he’d been riding in when the freight stopped at Brookfield half an-hour earlier.

You see, that freight had no sooner stopped than flashlights appeared everywhere-flashlights combing the train, searching every empty for "railroad bums," those unauthorized riders giving the railroads such a costly, coast-to-coast, Depression-time headache.

The boy knew he had to get out of the car he was in and get out quickly. Luckily there was a pile of paper in one of its corners-the wide heavy strips of paper they tacked on boxcar walls to protect shipments like bagged flour from soil and splinters, the paper that railroad bums sooner or later would pull down and wad up to make bed on empty boxcar floors. And so, with the flashlights coming nearer and nearer, the boy shoved his heavy old suitcase under that pile of paper and fled into hiding in the bushes along the track.

When the freight pulled out half an hour later there still were quite a few flashlights moving around, and about 20 cars went by before the coast was clear enough for the boy to fly out of the bushes and grab one. That's why, once aboard the train, he went running along the catwalk toward the head end. He couldn't know for sure which of the empties he'd been riding in, but he knew that he could get pretty close to it and then, the next time the freight stopped, he could quickly get reunited with his old suitcase.

He'd covered five or six cars when, a couple of cars ahead, he saw a man lying face-down on the catwalk. Just another railroad bum, experience told him, a bum playing it safe by laying low until the train got on down the road.

But experience told him wrong.

He wasn’t e few yards away when the man leaped to his feet and stuck a pistol in his face. He was a "railroad bull"-a common slang term for railroad detectives-and he ordered the boy to sit down.

The boy proposed an alternative. With the detective's permission, he said, he'd be off that train in ten seconds and, hope to-die, would never hop another one.

The detective snarled at that. The train had to slow down on a grade about 12 miles out, he said, and until it got there the boy-if he knew what was good for him-would sit down and listen to what he had to say.

So the boy sat and the detective, still holding his pistol ready started talking.

He used language that would make Norman Mailer and Erica Jong look like amateurs-incredibly foul language to express thoughts so incredibly foul that only a sick mind could have produced them.

The boy had no sisters but the detective, assuming that he had, cast them in repulsively obscene roles, laughing as he talked.

And then he changed the subject to the boy's mother.

In just a few seconds the boy was fighting to hold in the greatest rage he’d ever known.

And then the detective, obviously getting a sadistic thrill from the filth that tortured the boy, became distracted by it and unconsciously lowered his pistol.

The boy saw his chance. Sitting with his knees under his chin, he had only to lean back and lash out with his feet and pow!-backwards off that train that detective would go. He was all set, just a split-second from kicking straight out and then he couldn't do it. He just hung his head. The detective kept talking, stuffing himself with his perverted pleasure. And then, when the train finally reached the grade and slowed down, he ordered the boy down the ladder.

But hold on, you say.

Doesn't the headline say the boy killed the detective?

Yes, it does. And he did.

I know, because I was that boy. I wanted that man dead. It wasn't any sense of right and wrong that kept me from making that kick. It was plain old fear. Fear for myself. Fear that he might put a bullet into my head, and fear that if he didn't the electric chair would get me.

Well, then.. since I left him alive and unharmed, why do I say I killed him?

Because God says that whatever evil the heart yearns to do, the hand has already done. We have His word for it. It's not just the letter of the law that convicts, but the spirit as well. Not just the misdeed but even the wishful thought of it.

I was a grown man long before I saw any meaning in that night on the train, but now it's come across the years many times to remind me that there's no sin so forbidding that I'm immune to its temptation. To help keep me aware of the fact that, thanks to the human nature that's with me until the bell tolls, I'm a full-time full-fledged sinner.

VIRGINIA

Robert Murphy

Some families remained intact and suffered through it, while others were literally torn apart. There are people in our country today, including myself, that still carry the emotional scars of that God-awful time in our nation’s history

WASHINGTON

Art Grover

(Missionary)

18/1933

Left Illinois home…

”Soon learned what they meant by the term “mooch”. I did this only on two occasions. I always offered to do work for food and learned that the black people’s homes were the best. They were willing to share and some gave a dime, a quarter.

Don’t remember any one asking me to work. I do remember getting biscuits and molasses. Very good and energy-giving. This was great to see God provide my every need.

The blacks were more compassionate than others and willing to share at least something of what they had.

Rode the blinds of a passenger from Little Rock, Ark. We took on water as we left the station and at the high speed we soon had frozen stiff clothes as we were both covered with water. Without gloves we soon became very cold and the other man said he wanted to let go as he couldn’t hold on longer. I felt like it too but I put my arm around him and prayed for strength. When we finally stopped and we both fell down. I thanked the Lord for his strength in time of need.

WASHINGTON

Arvel "Sunshine" Pearson

born 1915

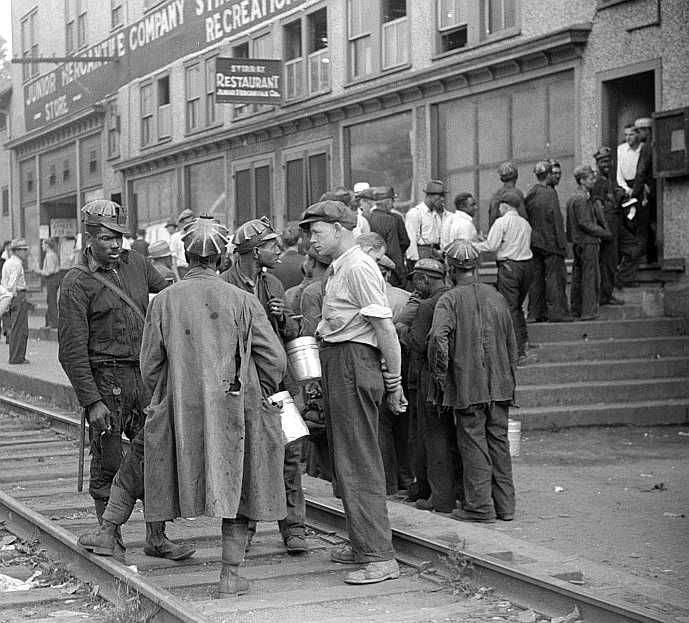

I was 15 years old in 1930 and already had two years underground in the mines with my stepfather.

"Took my first job carrying water at a strip coal mine for ten hours a day at five cents an hour, no one had ever heard of Child Labor Laws. If a kid got $3.00 for six days work that was bringing home the bacon.”

At 13 I graduated from the waterboy job and went into the mines with my stepfather.

He'd had some railroading "side door pullman style" in his younger days. Mine closed down. He said, "Go west, young man" and that is exactly what I did. My idea was to go to Alaska. Only at the border, after 3,000 miles, did I learn that there were no trains.

While hoboing in Louisiana I met a kid from Missouri. His mother and father had passed on, leaving seven boys from age 10 to 19. But in those days no one had ever heard the word homeless. In summertime they slept in a haystack or under the stars and did chores for some old farmer for something to eat.”

"On purpose I wore a striped shirt and cap. A lot of people thought I was a railroad worker."

I went to work hay in the Bittercourt Mts. The man I worked for was an eight-hour man. It sounded good. Except that it was eight hours before lunch and eight hours after lunch.

Chicago World's Fair

Elected youngest King of Hoboes in 1939, when I was 25.

"Dirty Thirties"

We didn't call it a Depression. It was a "Hard Time."

At Washington with Bonus Marchers: "I had a different picture of MacArthur burning people out of Washington."

WASHINGTON

Bob Cameron

My father was an ex-British sergeant-major and sorry to say never forgot it. In 1935 at 15 years I ran away from home.

The great compound engines of the S.P & S…

To give you an idea of the awesome power of these engines, I rode on the top of a box car up a 6% river grade at Pasco, Washington behind a SP&S Mallet pulling 129 loaded boxcars. An empty boxcar at that time weighed between 30,000 and 40,000. It was a compound engine with two steam pistons on each side of the engine, each one driving 4 wheels and measured 127 feet from draw head to draw head. It had at that time a long low moaning air horn that I think would make my feet itch again to hear it.

WASHINGTON

Channing L. Smith

Summer 1935 x 16

I learned that the freight I wanted left from Renton, a smaller town about 30 miles Southeast of where I lived. It left in the evening, after dark, and went to Portland, Oregon. From there I would try to get a freight that would basically follow the Columbia River, and go to Spokane, Washington. From there, I would catch a freight back to Seattle, or Renton.

I made this trip. I didn't have much money, but even though I got quite cold and hungry at times.

Traveling East, on a flat car, after leaving the Columbia River, a puff of wind caught my brand new broad brimmed hat, and sailed it down a canyon.

Coming West from Spokane, I was in an empty box car with two other men. One was an older man I'd estimate to be about 50 or 55. He had been bumming around, looking for work, with little or no success, so he was going home to his family for a while. He lived in Yakima, Washington and was quite pleased to be going home.

As we came into Yakima, the train started to slow down, so we said our goodbyes. This fellow then slung his pack on is back and sat down, feet out the door, ready to jump off. The other fellow and I were standing in the door to watch him go.

When he got about here he wanted, he hollered goodbye, and jumped out. Somehow, the train, 'n passing, hit his pack and spun him, and threw him under the train so far we couldn't even see him.

We were absolutely, heart-stoppingly stunned, as we looked back at the point he went under... Then, we saw him crawl from under the train and stand up, all in one piece, terrified and crying. We breathed again.

Eastern Washington is very dry, and I had made the mistake of not carrying a canteen. I was getting very thirsty, and hungry, when the train started to climb up into the Cascade Mountains, and began to slow down, almost to a snail's pace. Looking forward from the box car door, I saw a shack ahead - the only sign of life I'd seen for hours. It looked to be about 500 feet from the train track, and up a small hill.

I figured that if I were lucky, I could run up there and if anyone was around, maybe I could get a drink of water. I got about half way up, when a man stepped out of the shack - he apparently had been watching my run. When I got up to him I asked for a quick drink of water, so I could get back to the train. He gave me a drink of water, and told me to wait a minute. He went into his shack and brought out 2 loaves of bread, and shoved them into my hands.

I had no time nor inclination to argue so I thanked him and ran back to the train. I've often thought of the sheer generosity of that man living in such a shack, so isolated, and probably owned little more that the clothes on his back, to give two loaves of bread unasked for, but really appreciated to a dumb kid who had no better sense than to ride a freight train. Wherever you are, friend, maybe this will affirm my thanks. I was hungry.

1934 -1937 I was the champion apple picker! 3314 boxes of 60 pounds each at 4.5 cents a box and bonus of .01c at end of harvest.

The most degrading, sickening and dehumanizing situation I saw first hand was a man with his wife on the reefer car. He was selling her for 25 cents a time to as many men as he could find…

My experiences made me understand and view in a new light the injustices men and women of our country have faced.

WASHINGTON

Duval Edwards

Excerpt from The Great Depression © Duval Edwards

Ran away from home at age 16. Summer of 1932

“I began to look forward eagerly to the coming school term in September, until the day summer was almost gone, when the roof fell in.

"I happened to overhear Mother ask Dad for some grocery money. I saw him pull out a single, wrinkled and torn dollar bill, hand it to her, turn, and leave the house without saying a word. I watched him with his battered cowboy hat, grim-faced, get into the old Model-T truck, set the hand brake, the spark and gas levers, get out and turn the crank, hop in and slowly rattle off.

"For the first time my eyes opened all the way, and the full extent of our situation dawned on me: It was desperate.”

First job as Golden Gloves fighter against Kid Onionhead.

Watering elephants in circus, expecting to get paid, instead got two free tickets.

On 17th birthday woke up to find that someone had stolen shoes in night.

WASHINGTON

E.L. Childers

I was 15 years old when I left home in Marshfield Oregon in December 1931. I had six brothers and sisters. We did not have enough to eat. My little sister died of blood poisoning. I cried for six months.

I rode the rails for two-and-a-half years.

I went to a lady's house. She said I could mow the lawn for something to eat. I worked two hours with push mower. I had nothing to eat for three days. I finished the yard and asked for my food. The lady said I had to do the back yard also. I was so weak I couldn’t do it, so I just went up the road crying.

I offered some black boys some bakery stems. They wouldn’t take them 'cause they said my white friends would disown me if they were my friends. The blacks were treated like animals.

WASHINGTON

Ernest Amundson

Well, Chuck (he was the hospital orderly) thought we'd better get out of there, so we packed our stuff real quiet and caught the kitchen truck going to town, Bozeman, 25 miles. While in town we went down to the railroad station. I knew about riding on trains so told Chuck, let's take the passenger train and ride the blinds up on the water tank of the engine.

I tell you that was a cold ride 25 miles or so down to Livingston, Montana. Remember, this is February in Montana. When we got off that train we were cold and started walking down the train tracks toward the round house and when we got there some brakemen saw us. We must have looked bad or cold, because they had us come to their lunch room and gave us a sandwich.

That is the only time I ever had anything like that happen to me, but we had on our C.C.C. clothes. The brakemen helped us catch a freight train out of Bozeman. We looked this one over from one end to the other and no empty box car.

Only thing empty was a qondola. For someone that doesn't know what it is, it's a boxcar without a top and only half as high as a car. The trains haul coal in these. Anyway, we took that car. We had lots of clothes on and some more with us in our barracks bags. We got on the train and pulled out.

It was a very dark night, and very cold, so after a little time we just sat down and just got colder and colder. after a while I began to get warmer and sleepy. It this time I knew I was starting to freeze and if my folks had not told me this is what happens when people start to freeze to death, I would have sat right there and both of us would have frozen to death.

I got up and started walking back and forth in that car. I could not see my hand in front of my face or anything else. I was sure cold. Had on lots of CCC clothes, underwear, 2 shirts, 2 pairs pants, a coat and overcoat. These were all wool clothes. I was not warming up, so I started dog trotting with my arms out in front of me so I could feel the end of the car with my hands and not my nose. I don't know how long I did this, but I finally warmed up.

Then I thought of Chuck, and he was still sitting there, so I tried getting him up. Well, this was quite a job because he would not get up. He wanted to sleep and said to leave him alone. I knew what would happen to him, so I would not leave him alone. He hit me with his fist and kicked me and laid down, etc. He would not get up. I sure got warm. I took my overcoat off and just kept fighting him, until I got him up.

Then he wouldn't move, so I started pushing him from end to end of that car. He soon learned to hold his arms up. I must have pushed him two or three times, maybe more, until he would do it on his own. He thanked me afterward. So there was no sleep that night. I put my coat and overcoat back on after a while. We were sure glad to see daylight come.

When that train stopped, we got off, went up town, found a store and bought some things to eat. Loaf of bread, fruit, apples, some milk. Then we went back to the train tracks, waited for the train and watched. It was doing some switching of boxcars. Well, it hooked on to some empty boxcars, so we were able to get an empty boxcar from there. We stayed with it all day and all night. We caught up on our sleep during the day. We got into Miles City the next day.

WASHINGTON

Frederick Watson

We had moved to Pocatello when Dad got an upgrade and a better job in the Union Pacific yards in Pocatello which was a large division point. The yard was almost a half of a mile across and was a much more complex affair than Lima. It was less personal because it was so huge.

You did not run all over the yards at Pocatello like you did in Lima, because there were fences around it, and guards and all the associated things that go with that. With Lima being so small there was none of that. They did not have to worry about it; heck, there was only a half a dozen boys in town. We lived on Clark street on the west side of town and naturally almost all our family's friends were railroaders.

We had Mr. Riggs who lived across the street from us who was the railroad agent, Mr. Waring was the station manager who lived down about a half a block. Our neighbors on each side of our house were Mr. Hitler and Mr. Hard. Mr. Hitler was a conductor and Mr. Hard was an engineer. They both worked on the same train, the "Portland Rose".

These two gentlemen, and my dad, would get together every Thursday night for cut-throat pinochle. To this day (I'm 73 years old), I cannot remember those gentleman by referring to their first names. In fact I have to think a little to remember their first names as they were always Mr. Hitler, Mr. Hard, and Mr. Riggs, etc. Quite a change from today.

Mr. Hitler and Mr. Hard would argue in this pinochle game, which was always played at our house as we had a big round table acceptable for playing cards. As long as I remember (we lived in Pocatello 10-15 years) my dad and the other two played cards every Thursday evening.

Over the years Mr. Hitler and Mr. Hard got to be real bitter enemies over this card game. Even though they worked on the same train, they would not speak to each other, except in the line of duty. In those days, they always checked their pocket watches to be sure they were synchronized. Mr. Hitler and Mr. Hard would check their watches without a word, then go back to their duties. The only words that were ever spoken was those that were necessary in running the train. I guess to their dying days, they continued with this feud. It never became violent, it just had no talking or anything like that, except in the pinochle game. Odd how character runs.

My love for the railroad continued on into and during the Depression. As you know, there was very little money to be spent. If you wanted to go someplace, you either walked, rode your bicycle, or hitchhiked. There were no cars on the road to speak of; there was not enough money to buy gasoline for gallivanting around. You could go out on the highway and wait there, one or two hours before a car would come by.

As a result, my friends and I would ride the freights. The freight train in those days was our mode of transportation wherever we wanted to go. We timed all of our escapades out of town per the schedule of the freight trains -- to the swimming hole, favorite rock climbing face, and any number of activities for which the railroads provided our transportation.

Bud Hupp, whose father was a postman, and Russell Jensen whose dad was a shopkeeper in town and me would go all over together, riding the trains, swimming, etc. You name it, we probably did it.

One of the favorite ways we kids had to make spending money was placing pennies on the tracks of a slow-moving train. We would put a couple on the tracks and wait for a train to run over them, then sweep them off and place a couple of more on. These pennies were elongated by the wheels.

You can get them now in "Penny" Arcades. They are made by a heavy drum under terrific pressure. Cost a dollar or more now. They got the idea from kids like us.

We would save them up to sell at the summer fair. As I recall we got a dime for them and we would sell all we had. We would make maybe four or five dollars, and boy, that was big bucks!

In those days, the freight trains were made up of box cars, reefer cars, flat cars, gondolas, and oil cars which were all accessible. The trains on the rails today are all diesel; piggybacks, etc, are not very interesting anymore. During my days, there were always open box cars and with us being children, just small lads (about 11-12 years old), we were still too small to swing up into the box cars through the open doors. They were over four feet off the ground - that was not much more than we were.

Therefore we were relegated to jumping on the car and crawling up and riding the top or getting into a gondola, or riding on the tailgates. We never rode the rods as that was too dangerous for us. The term "Rods" alludes to the support rods that ran the full length of the car. There were about four of them a foot apart. Very uncomfortable to say the least. These were the days when the hobo was king of the road and every train had hobos on it.

You see motion pictures today of the mean old brakemen and such as that, but with all of the dealings that I had with the trains, we never ran across a mean brakeman. They were amiable people and we tried to dodge them and did not give them a rough time. We left them alone and they left us alone for the most part.

It was a little dangerous running and catching these trains. We would have to catch them at the start of the yards while they were going slow. The first thing you did was look down the road to be sure you had about a hundred-yard run that was not obstructed with a switch, a tower, bridge or any number of things that could interrupt your run. You would then run and concentrate on the handbars and crawlbars of the train. Just as you were at the right place, you would grab the bar and swing your feet at the same time and jump on the lower bar.... Away you'd go, you were on your way. We would usually climb up to the top of the boxcar and enjoy the view as we went gallivanting.

It usually was good weather. We did not ride the freights in the winter as it was too cold and miserable; it was strictly summertime travel when school was out and we wanted to go swimming or to Indian Hot Springs or American Falls Reservoir. At that time, they were just building the American Falls dam and it was quite interesting to watch the construction.

We would ride the freights and watch the workers for a couple three hours and then take the next train back. We had all the schedules of the freights in our minds and knew when they went by in almost every town we happened to be in, so we never had to worry about it, we just watched what we were doing and got on the right train.

Nobody had a watch, we just watched the sun, and listened for the whistle on the outskirts of town and we knew we had about 15-20 minutes to get down to the yards.

We never had any trouble with hobos. We would get into cars when the hobos were good enough to reach down and swing us up into the car with them. We'd sit there and shoot the breeze with them for awhile as far as we were riding and then we'd get out. Getting off a train is a little different. You still have to look for your run path to be sure you are not impeded.

For the most part, however, we rode the tops as it was more interesting up there as you had a view of the scenery and all of the countryside. The trains would travel at approximately 35-40 mph and were not going too fast.

We never rode the passenger trains or the "Varnish," as they used to call them. The only place you could ride on a passenger train any way was either on the rods or in the blinds. The blinds is that open end of the passenger car.

Most of the time, we would ride the trains out west of town to American Falls, there was a hot spring there. We did the same thing east of town to Lava Hot Springs. We didn't go there very often, but one time we hopped a freight that was for the most part a string of empties.

The engineer took advantage of the downhill grade as he must have been behind schedule, and went through Lava Hot Springs at about 55-60 mph. We were riding gondola cars. It was going too fast for us to get off. We had to stay on and we rode for another 55-60 miles to the next town before we could get off the train.

We passed the train we would normally ride back on as we were going the other direction. There was not another train until well after 11:00 at night. We didn't get into town until 2:00 in the morning. Boy, if you don't think we caught the devil over that!

There was a pretty extensive hobo jungle on the west side of town; sort of a bulrush area near the Portneuf River. There was always a population of hobos there of about 100-150 people.

There were entire families; wife and kids. They were good solid citizens who were flat out of work, had no place to go, were kicked out of their homes, lost their jobs, had no money, and were looking for something to eat, trying to find a job someplace...

There was only one way to travel for them, and that was with the train. In many respects, the railroad was understanding in this and did not raise too much of a hullabaloo over it. These hobo jungles were not as bad as they have been depicted in films and books. For the most part, they were fairly decent citizens and almost every big town around a division point of a railroad had its jungle and Pocatello was no different.

Two friends and myself would go out there occasionally and talk with some of those guys who'd been there a year or more. They eked out a living, panhandling, working when they could. They did not panhandle too much because the police in town were not too pleased with that. They would go around and cut lawns, etc and earn enough money to get by. They would make jungle stews for dinner. Each man would bring in an ingredient; one would bring beans, another potatoes, another carrots, turnips, or whatever and would make this big pot of stew. This was sort of a community pot and everybody would partake of it.

We got to know some of these guys real well and would have lunches and dinners with them. We would take our share with us. Most of the time, coffee was what was really desired and we would purloin it from our homes. Mom and Dad probably knew about it but they didn't say anything. We would stay with these guys and visit with them.

The hobo jungle was a community within itself. It had its own governing rules, its own police force if you will, there was usually a mayor elected by the men. The families were well respected by the others and were left alone and were not bothered. There was no crime around there and I do not remember one crime in Pocatello attributed to a hobo. They were just poor men trying to get by, finding someplace to get a job. Most of them were married with families still at home with the man out on the road trying to find a place to work and live so he could send for his family. Some of our family's best friends started out as hobos; would come to town, get a job and become a respected citizens.

One of the guys I bummed around with had a caboose key, his Dad was a switchman, and one key fit all. We had one old caboose that had been sitting there for years; still pretty well outfitted and we used that for a clubhouse. They never moved it and it gradually deteriorated.

Anyway we used that "crummy" as a clubhouse. We had a lot of fun there. We never hurt anything, never destroyed or damaged anything; not like today. When we left, we always cleaned it up and never left a mess. One day we headed for our clubhouse and lo-it was gone. We found out that they had scrapped it. It was like losing and old friend.

Other things we did was sneak around the yards and climb and play hide and seek on the cars and dodge the bulls (Railroad detectives). Over on the far side of the yard, there was a small locomotive sitting there called a backup switcher. This was in case something went wrong with the one that was out in the yards, they would have this backup available. A steam engine, being coal like it was, took quite a while to get charged up and heated to the right pressure so that it could take off. They would leave it on standby of about 80-90# in the boilers with banked up fire. The tender would come out about once every 4-5 hours and throw a shovel full of coal into it to keep it going.

All of us knew how to run trains, being all railroad kids and we decided to "borrow" this engine. We first had to built up pressure to about 150#. We ran it up and down the line but not too far.

What a temptation to blow that whistle and ring the bell but we didn't dare. If we would have, the whole yard would have come down on us. We did this a few times and then brought it back and parked it. We had a pretty good idea when the guy was coming around to stoke the engine. We'd load it down, pull the fire and slow it down so that they never knew the difference.

We realized the trouble we could get in for doing this, but boy, was that a thrill, and to have to keep your hands off that whistle....

There was nothing wrong with riding the rails in those days as it was almost a necessity if you wanted to get anywhere. Us kids took advantage of the railroad as much as we could. There was no other way to get around.

WASHINGTON

Gene Tenold

“…For the first month on the bum, you threw the food out if the flies got in. The second month, you brushed them away and ate the food; the third month and after, you knocked the flies back in the stew if they tried to escape.”

WASHINGTON

Gene Wadsworth

I was born in a small western town in April 1915. When I was two years old my father died and when

I was eleven my mother died leaving me and my four sisters orphans.

Different relatives came and took us to their homes in different cities and states.

I had just started my second year of high school, when one of my older cousins said: Why do you hang around where you are not wanted? I was about 17 at the time.

To this day, I’ll never know why I reached out and grabbed the rung of the ladder on a boxcar. I climbed to the catwalk, lay on my stomach and hung on for dear life. I had never been near a train before and I was scared stiff.

Sidetracked: “I raised myself up, looked around and saw the red tail lights of the caboose fading away into the night. They had sidetracked several cars including the boxcar I was on. The wind was blowing. I was half frozen. I heard a coyote howling off a ways. Not knowing where I was or what the surrounding area was I stayed on that boxcar and shivered.

Finally daylight came and the warm sun was wonderful for a while. A few hours later I could see the heat waves dancing out across the desert. The boxcar was an inferno. I had no food or water. I thought what a heck of a place to die. Two or three trains went by, but were traveling too fast to catch. By nite I was desperate. I had to get out of there. Around midnight another freight rumbled by and I caught it… I don’t know how far I dragged before I finally pulled myself up high enough to get my feet on the ladder.

But I had lost my flour sack. Now all I had was what I was wearing. I finally got between two boxcars and out of the cold wind, but the flying cinders stung my face and eyes. I had to bury my face in my denim jacket. I was getting an education the hard way….

It was about daylight when I saw a small river a short way from the railroad tracks. The train was slowing down for the Pocatello RR yards. I jumped off the train and rolled down to the Portneuf River. It was the best water I have ever tasted. Later I was told it was Pocatello’s sewer system.

There were a lot of low life riding boxcars. You slept with one eye open. I had a pair of iron knuckles. I could slip my fingers into the rungs –with the bar in the palm of my hand – hit and splinter a board. I used it only once and it saved my life.

Every time we would check into a transient camp or chow line or anything we would have to do it in alphabetical order. My name started with a W and that put me way back in the line. Lots of waiting so I changed my name to Ed Bebb. I didn’t want to be first in line like Abbot or Anderson – because I wanted to get acquainted with what was going on in front of me and have my answers ready. So Ed Bebb was my hobo name.

I met a blond young man, Jim, my size and age. Everyone thought we were brothers. We though a lot alike. We hit it off real good, so we teemed up and decided to make our fortune together. He had come from a broken family. He called his mother a bitch. I said that is no way to talk about your mother. All he said was, you don’t know my mother. I just let it go at that. We never discussed his family again.

All went well until one night Jim and I were riding between two box cars on the ladders. It was so cold my hands were nearly frozen. I had slipped my arm over the run of the ladder and had my hand in my jacket pocket. Being back to back, I couldn’t see Jim. All of a sudden the train gave a jerk that happens when the train takes up slack in the draw bars.

I heard Jim let out a muffled moan. I whirled around and made a grab for him as he fell. He had a knit cap on. I got the cap and a handful of blond hair. Jim was gone. Disappeared under the wheels. I got so sick I had to climb up and lay on the catwalk. No way could Jim have survived. I was a loner from then on. I never teamed up with anyone. Traveled alone.

Sometimes we would be so intent on grabbing the ladder that we’d misjudge distances in the dark and run into those flat switches that were about crotch high. Lots of hobos were ruined for life after running into a switch. It was not unusual to see a dead or dying hobo in the RR yards or in the jungle where he had crawled.

Escape from a bull in Cheyenne, WY: ”As the bull started down my ladder, we came to the crossing. I threw myself back as hard as I could and jumped free. I landed on one foot on the edge of the crossing, slid clear across the double road on one foot, stepped up on the side walk. Cars honked, people hollered and waved at me. I made a little bow, waved and walked up the sidewalk. It was a perfect landing, me, and the bull expected me to roll. I walked to the other end of the yard, around the town and caught the train out the next night.

Rode a cowcatcher: "What a hell of a ride I had, burned on one side and frozen on the other.

WASHINGTON

Hal Browning

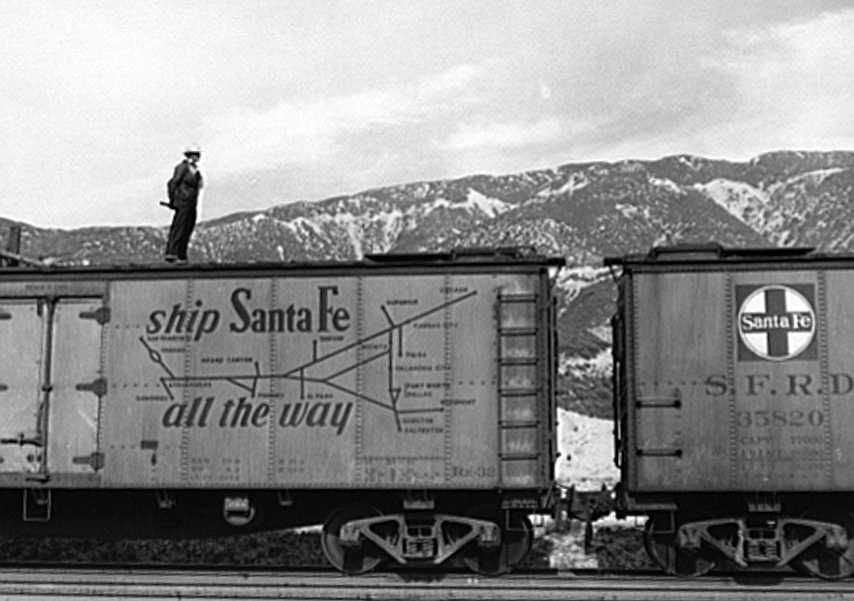

The year was 1931. Three young men stood by the Santa Fe RR tracks in the city of Los Angeles, near the dry bed of the Los Angeles river.

Picked up by the police and lodged in the old Lincoln Heights jail. The next day was Sunday but they held court anyway, maybe to get rid of transients and undesirables such as ourselves or maybe it was a kind of racket – who knows? We found ourselves in court with a woman judge.

I was tried first and charged with lodging (sic) in the LA riverbed. I told her I wasn’t lodging in any riverbed but just waiting for a freight train to get out of town. She was somewhat flustered at this point and said “Case dismissed”

My partners were not so lucky. She had regained her composure by the time they appeared before her, so they received the customary “30 days floaters.” If they reappeared within 30 days dire consequences were supposed to follow. We went right back to where we had been the night before and caught an eastbound freight.

The Santa Fe Railroad didn’t want people riding their freight trains. In contrast the Great Northern RR never bothered transients. Jim Hill the man who built the Great Northern said the hoboes helped him build the railroad and they were not to be bothered.

WASHINGTON

Howard Ferguson

16, 1931

I went to south Oregon, catching a train out of Portland.

Usually carried a blanket and slept where I could. Cardboard was a great find, except for the earwigs and critters that crawled out of it on your neck in the middle of the night.

Got off at Medford early one morning. Went to a nearby diner and asked if I could earn some food. Place empty except for a young waitress who sat me down, ordered up a big breakfast and after I had eaten gave me 35 cents so I could pay her and have it rung up. Pretty nice.

Being skinny and hungry all the time, I guess just finding food and surviving was about all the philosophy I needed.