LOUISIANA

Arthur Reibe

Tom Sawyer like adventure

"Riding boxcars to swim-hole and rafting down the Mississippi to join the French Foreign Legion!"

We lived in the town of El Dorado, Arkansas. It was 12 miles to the town of Calion on the Cuachita River so to get there our favorite fishing/camp spot myself and a buddy, James Hollis, would walk to the local freight yards of the Missouri/Pacific/Cotton Belt and inquire from the hobos which boxcar would take us north to Calion.

We always rode in boxcars on trips which was usually on Friday after school. We were pretty scared of being caught by the railroad people and more scared of the bums and hobos.

When the train would slow as it climbed the Quachita River bridge we would jump off carrying our blanket, can of pork and beans or sardines and walk the river bank to our destination. We would swim and fish over the weekend and return via boxcar.

Our folks would have skinned us alive had they known.

MASSACHUSETTS

Arvo Niemi

1932

Sold poultry journal at 16

Daring free ride on passenger train

Girl with gun in boxcar

One time I was in Central and was headed for Cairo, Illinois. About a mile down the tracks was a water tower where the trains stopped to take on water and that was the place to go. I heard two whistles blow, which told me meant that the train was starting up. I finally saw it and it was getting up speed, but I still thought I could catch it.

I grabbed hold of a low rung. My feet were dangling and I wanted to let go, but that would have been sure suicide. Then I felt an awful bang on both feet. There was some type of signal light or sign which I had hit and my legs seemed numb. I really wanted to let go but hung on and slowly climbed up the rungs. …”

Woman said I had to split a little wood. She left. I was still at it when she came back. I didn’t mean whole pile! She gave me lunch!

Another woman, when I asked for work, said “No, I also have a son on the road somewhere. I hope someone is going to give him something to eat."

Sister Theresa

Recalls story of poisoned oatmeal in garbage to kill rats: killed three transients in Mount Greenwood area of Chicago, 111th Avenue

My family lived in the Mount Greenwood area of Chicago. It was at the end of the line for the street cars and many of the so-called “knights” passed that way in the winter of 1931-1932.

On 111th Ave., the Consumer Grocery Store was located near Hayden Realtors and the local bank. The refuse that they discarded was put out in the back of their store where some was burned out in the open. Because it was in disarray during the day, rats had begun to feed in that area too.

To rid themselves of the rats an employee put poison in an open oatmeal carton and left it to attract and eliminate the pests. The same night three or four men who had traveled by rail found the discarded, half-empty cartons of oatmeal. Hungry and cold, they built a fire, melted snow in tin cans and cooked the oatmeal… their last meal. The following morning they were found dead in the refuse.

These men had left their homes looking for work in the city. They had traveled a distance to find help for their families. They were strangers to one another but they had shared their meager meal to sustain life and had earned the same fate … a very difficult death. Because this happened in our neighborhood, I never forgot the story. It made a deep impression on me.

MARYLAND

Alexander Gretes

15

My family operated the Brooke Avenue Confectionery in Norfolk, VA, just one block from the Chesapeake and Ohio and the Pennsylvania Railroad terminals. Very often during the Depression hobos would come to the store and ask for food.

As a high school student I would work in the store after school until closing at 10.30 p.m. My homework was done on the counter between customers.

One evening while reading an assignment on Shakespeare’s Macbeth, a hobo came into the store. He was poorly dressed and somewhat introvert.

Apologetically he asked, “I’m riding the rails, going south for the winter. I’ll scrub your floor for something to eat.” He was given two sandwiches and a cup of hot chocolate.

As he finished eating, he asked, “Which of Shakespeare’s plays are you reading?” My answer, “Macbeth.”

He then asked, "Tell me the Act, Scene and Line you are reading now." I did. He then, from memory, quoted the passage beginning on that line.

He then asked that I do the same at random. He again correctly quoted the passage. He thanked me for the food, again offered to scrub the floor and left.

To this day I still wonder who he was, a former Shakespearean actor or an old Professor of English Literature. He never said and I was so astonished I didn’t ask. Anyway it wasn’t proper to ask.

MARYLAND

George Hanson

Rode trains from St. Paul to New York

What happened to me in the past half-century plus except for a few high moments later in life -- everything was sort of anti-climactic beyond the immediate three weeks following graduation.

“We of the lost (and always jinxed) generation."

Baltimore Evening Sun, May 18, 1983:

"It was in the very depths of the Great Depression when Mike and I graduated out of high school in Minneapolis into absolutely nothing.

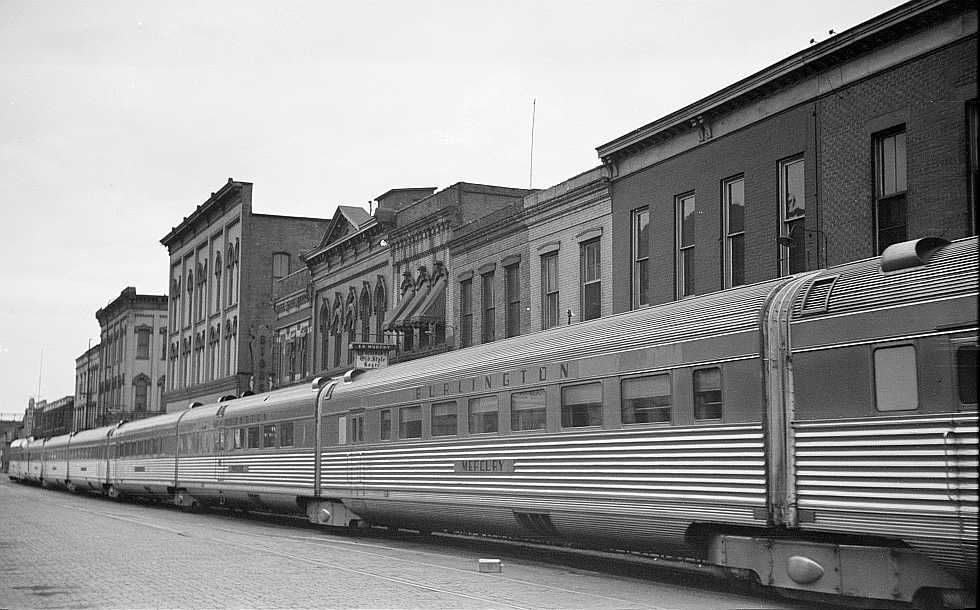

That night by spread-eagling ourselves atop one of the baggage cars, we successfully passed in and out of the tough railroad towns of La Crosse, Wis., and Aurora Ill, making it through aboard the Burlington’s “Blackhawk” passenger train all the way to Chicago.

We had then caught another passenger train out of Gary Indiana bound for Detroit. This train turned out to be a local, stopping at every town along the way, and for us, all without incident. This had gone on all night and the sun had been up for a couple of hours when it happened. (Daylight riding in the blinds was considered a very risky business)

Coming over the top of the coal pile the fireman suddenly appeared. Shouting over the roar of the stack exhaust, he said “I’ve got a message for you guys from Big Joe. He’s the engineer up front and he says to tell you that there’s gonna be a big reception committee of about a dozen bulls armed with guns, blackjacks, pick-ax handles and baseball bats waiting just for you and they won’t be satisfied with themselves until they’ve made sure you’re both dead.

"Right now were about a mile from downtown Detroit station where this train’s run ends. So in a couple of minutes Joe will slow her down and at the right instant he’ll give a toot on the whistle and when you hear this jump off. Now he can’t slow her down too much cause he doesn’t want to get fired over you. She’ll still be going pretty fast but if you don’t get off then you’re still going to get yourselves killed.”

With that he was gone over the top and down into the cab.

Soon we could feel the power go off and the brakes being eased on slowly brought the cars together, then came the short toot on the whistle.

The train had to be doing all of 20 miles an hour when we bailed off into a long, painful blurry somersaulting skid through the ever sharp trackside cinders.

Oh, it did hurt, but of course it was all so much better than the fate waiting up ahead at the brutal hands of a dozen angry men.

MARYLAND

H.J.Heller

Daughter sent clipping by Heller, a UPI staff writer who died in 1986.

“It was about 3 o’clock on a cold June morning when a dozen of us were kicked off a freight in Bloomington, Ill.

Cold hungry and chilled by the overnight wind, we sat on curb wondering where our next meal would come from.

Suddenly a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce rolled up. An old woman clad in a fur coat got out.

Walking along the line of hobos she reached into a huge handbag and handed each of us a nickel.

Then without saying a word she got into the car and was driven away. Who she was and what motivated her none of us knew or cared.

The nickel bought us hot coffee and stale buns at a cafeteria near the tracks.

In the railroad yards of the Denver and Rio Grande (dubbed the Dirty and Rapidly Growing Worse by the hobos) in Salt Lake City, about 20 transients were waiting for any freight headed eastward.

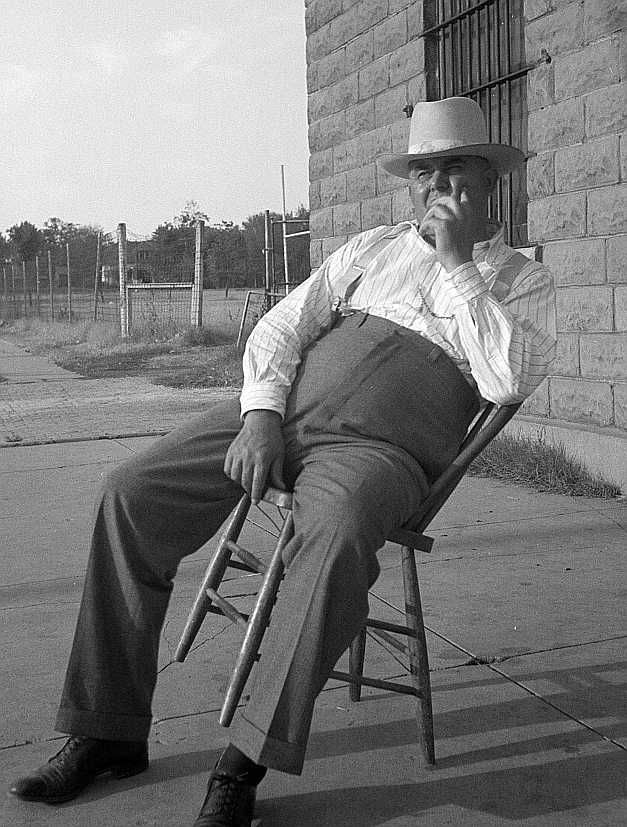

While I was sitting on a track on a hot summer afternoon, a chubby young person dressed in a jacket, trousers and a pork-pie hat approached with the salutation, “Hello, Slim.”

The hobo was from the Terra Haute, Ind. area and was plumb tired of farm chores and wanted some excitement.

It came sooner than expected. A group of railroad detectives arrested us and began to search for weapons. Most of us submitted meekly but the hobo from Terra Haute fought like a cornered tiger.

It turned out that the bo was a young girl and resented the fact that the detective didn’t stop patting her down. She and all but three of the others were taken to jail for clean-up chores.

I was one of the lucky ones, probably because my clothes weren’t quite as ragged as the others.

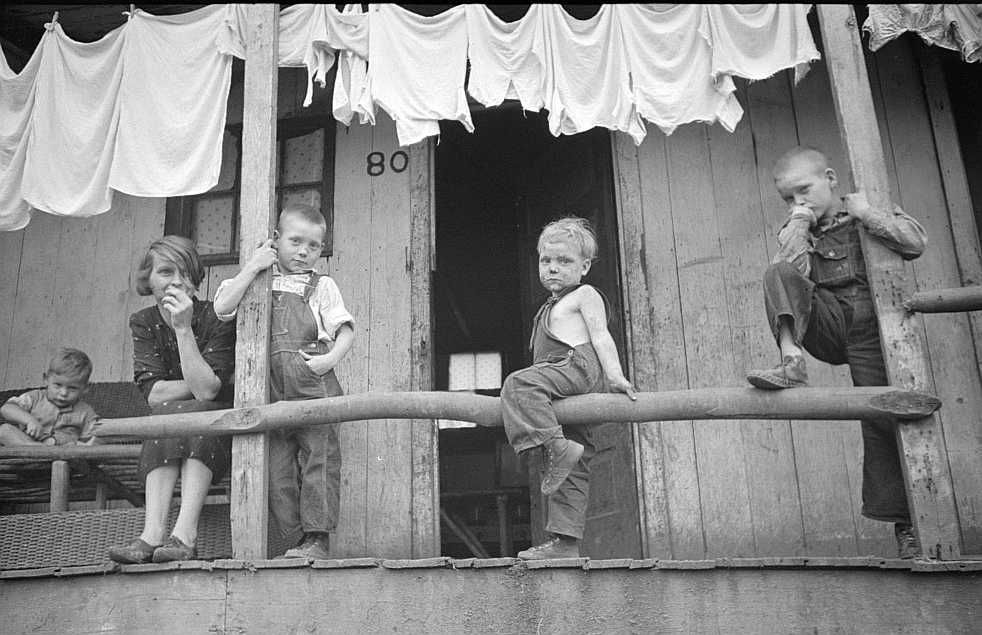

The most pitiful sights on the trains were the women, some of them nursing infants. For the most part they were the wives of migrant workers scratching a few dollars in the fruit orchards in various parts of the country.

Their presence on the trains was welcome to hobos, possibly for selfish reasons. Railroad detectives tended to look the other way with women and children aboard.

However in a different context the saddest thing of all witnessed from the “side door Pullman” was not the women and children nor the shacks occasionally glimpsed down roads in dust bowl areas. It was the wheat fields – and the people in them, most often just one woman driving a vintage tractor in a field that seemed a mile wide.

Invariably as the train rushed by the engineer would blow the whistle with a long woo-hoo and wave to the woman form his cab.

And just as invariably the woman would turn and wave back and continue waving until the last fright car, with the last hobo was also waving, disappeared down the track.

The loneliness of the woman (which she may not have felt at all) was almost tangible and often I was close to tears. But at the same time I was happy to be on the train moving eastward.

MARYLAND

Johnny Layne

With friend Jesse Borden

Johnny started riding rails at age 12

"A woman in Centralia sat me down and fed me. Gave me paper to write home to my mother. Said she had a boy on the road too. Handed me $2.

"On our trip to Chattanooga, TN, we had 25c. Jesse said... 'I'd like to go to New Orleans'

Decided we would flip a coin: 'Head to New Orleans, Tails to home.' Flipped. Heads!"

MARYLAND

Joseph Zang

1930-32

13, 14, 15

On the way to Altoona, Joe Louis jumped in my boxcar. I met him and he told me then that someday he would be champion prize fighter of the world.

Joe Zang grew up in Baltimore. Sold newspapers on the street for six to eight years. Singing and playing the ukulele as he sold newspapers, he became known as the Singing Newsboy. Hit hard by his father's death at age 11, he was forced to go to work at age 13

MARYLAND

William Hewitt

1934, age 23

worked stint as a yard clerk

It made me appreciate my good luck. It also made me realize that people get down on their luck through no fault of their own. As a result of the experience I am more tolerant than I might have been otherwise. It also made me not become too self satisfied because misfortunes come unexpectedly. I appreciated my job more, worked harder throughout my life.

MAINE

Francis Gerath

17 -18

1933/34

rode rails and hitched

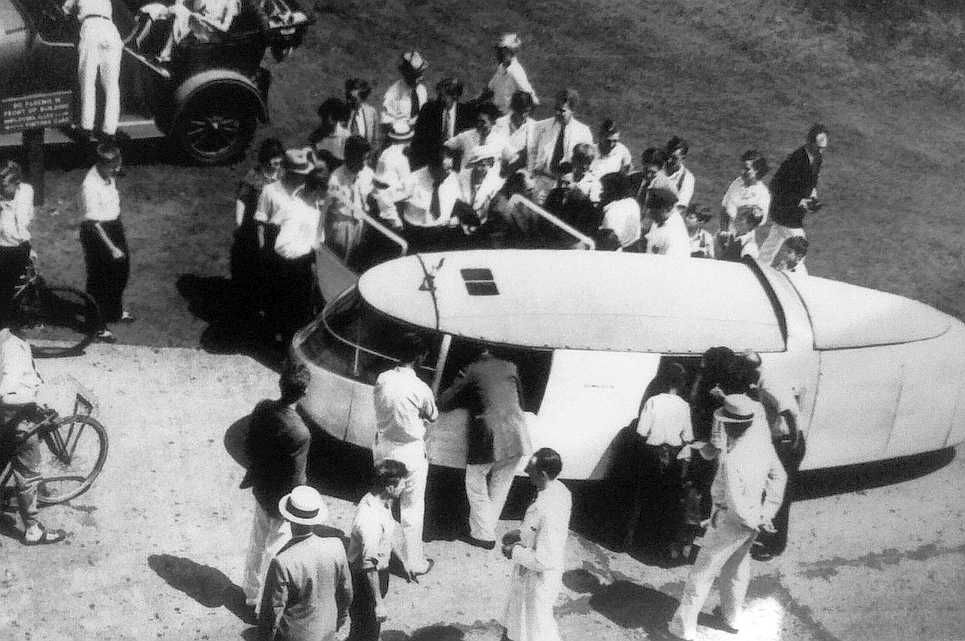

Buckminister Fuller, the world famous engineer and philosopher, picked me up in Chicago and took me to the east coast in his newly invented car, the Dymaxion Flying Fish. It had three wheels and was made of aluminum. Held nine people and went like hell.

Buckminister Fuller was a very kind man. Paid for my meals when I rode with him. Found out later that he was broke himself.

Wandering like that began to scare me. I was beginning to like it too much. I realized I had another life to live.

MAINE

Irving Steven

Great Depression hobo for nine years.

A boy watching trains go by...

“To a dreaming, lonely boy of nine, it was a marvelous experience and the highlight of many a summer’s day to count the cars on a long freights and to note their faraway origins. It was an easy geography lesson.

“During one such lesson, while I watched a slow freight pass, my attention was diverted to a slogan painted on the side of a Great Northern Railroad boxcar, “See America First.”

One day, through necessity, I left my hungry home and pretended to look for work, hoping of course that no unsuspecting soul would hire me. Not having much education or training, my place in the scheme of things was uncertain. The drinking route had fizzled out as it left me remorseful, so I chose to “See America First,” and during nine memorable, boxcar happy years, I discovered I was a scenery bum.

Even after 40 years, I sometimes ease open the front door at night and unconsciously say to myself, “What are we stopping here for?”

When the N. & W. southbound slowed down, I boarded a 'hopper'. Maybe at Norfolk, I would join the Navy!

Before arriving in Portsmouth, a warning was given me by track workers about being picked up while riding a freight between the Ohio River and Bluefield, West Virginia. I paid them no heed, thinking I was much too smart to get nabbed. The brick kilns at Portsmouth kept me warm that night, until I was chased out early in the morning.

A freight was going over the Ohio River, and I rode it all the next day into the mountains. The sun grudgingly sent its rays over the tops of the trees on the low, smoky peaks of the Appalachians. It was a welcome relief when, late in the morning, it reached down over the sharp embankments to bathe the tracks below with periods of warmth. The cool mists never fully cleared from the friendly mountain natives’ humble homes.

Some of the natives eking out a living on a one mule coal mine were no better off financially than myself. Many small family mines had been abandoned altogether, since the price of coal hardly made the digging worth the effort.

When least expected, dark, clammy tunnels wou1d swallow the freight, further dampening my spirits. It was always a relief when the rattling, bucking string of gondola empties broke into the hazy sunshine along the curving roadbed. The day had progressed into late afternoon. When the coal-hungry freight slowed down, I planned to take to the highway, or even walk the tracks to get warmed up. It finally came to a screeching halt that nearly threw me to the bottom of the gondola!

Upon looking up, I found a 'hog-leg' was stuck in my face ! Hadn't seen one of those since Chicamaugy. Time sure flies when you ain't payin' attention. First impressions told me the mean looking character behind the long, ominous barrel obviously hadn't received his education from the playing fields of Eton. I would do best to take heed before that long-barreled pistol he was holding blew up in my face! The freight started again with a lurch.

He warned me before we entered the next tunnel, if I made a move going through there, he would blow my head off! He kept lighting matches to see if I had.

A railroad bull had been killed in the line of duty a few weeks before, and they hadn't been good humored since.

Well, the rumbling freight slowed down enough for us to unload just before it passed through a small mountain town. On top of a high embankment stood a shotgun man who watched me, while a crippled old man was being coaxed from the moving gondola. Before the freight was stopped, this old Bo had been sitting at the end of the gondola. hanging onto the bars. Very shortly, he and I would be hanging onto other bars.

On the front of a building, up over the embankment from the tracks, a sign read, 'McDowell County Court House'. Inside were several off-duty railroad bulls, home guards, and constables bunched around, looking like a 'kangaroo court'. They were right in assuming I was a dangerous character, already looking for a way out.

At once, a voice piped up from the back, saying, "You are accused of trespassing on the N.& W. railroad. Thirty dollars or thirty days. Case closed!" In my best courtroom manner, I spoke for the defense, saying, "The defendant worked for the N.& W. last year and should be entitled to a free ride."

I was given a free ride to the county jail where I was thrown in with others who had just climbed down from some dump trucks. Several guards were unlocking the ball and chains and leg irons from a mixed group of whites and blacks, possibly twenty-five to thirty-five men. We were soon acquainted, four to a cell, with one john and one wash basin.

For supper we were served rice with a heavy syrup, corn bread and a big tin of hot coffee. About the same for breakfast. Dinners were stews or beans or more rice, more of that good corn bread, and coffee or tea.

Outside of this 'resort' town was the quarry where sixteen pound hammers chipped off the little ones from the biggies. Roads were being built, compliments of 'Bones' and company. On one Sunday morning we were shackled up and taken out to the main road to clean up a mud slide.

The 'shackle' had the length and looks of an ordinary pick-ax. A hasp with a lock would be opened up, and, to prevent the ankle from being irritated, a rag from an old blanket would be wrapped around it. At dinner time we wore the awkward contraptions to the cell. "Clankety-clank.

For two days we worked around the town's alleys, giving it the spring clean-up. Assorted trash, cement blocks with iron pipes in them, and a junk car or two all waited for our attention.

Would you believe, a Virginia friend and I devised a scheme to make a break for it! We were in dull company and the work was absolutely boring, to say the least.

Back at the jail at dinner time, the locks on our shackle hasps were broken open and covered with rags to escape detection, From the edge of the quarry, where we had hidden our jackets, it was about sixty yards to the trucks,

"Don’t give up now, we are almost out.”

Before the trucks moved out, the guards were busy locking up the tools. Someone was forever stealing them, While others were loading, my friend and I planned to hobble back a-ways, take off the shackles and make a break for it ! A scheme like this would go over big in Sing Sing.

Quitting time had come: the trucks were nearly loaded up; the guards were off to the side, busy, I nodded to my friend to come on, but he froze I hobbled towards the quarry and was about to shake off the leg iron when one of the prisoners hollered, “You are going to miss the truck!" You don’t have to wonder now why some never make it beyond the fifth grade ! “Heck," I hollered back,"I’ve got to get my coat at the quarry.”

My Virginia friend was already serving extra days for minor infractions of the rules; perhaps this explained his reluctance to carry through on the breakout, One thing I know for sure, I wouldn’t be around to quarterback his next escape plan. Up and over the quarry hill was the Virginia state line.

Suddenly, the guards came to the conclusion a good hammer man was about to get lost, so they came back to help me retrieve the two jackets, Although I never saw anyone physically abused, I often wondered if those shotguns were loaded! In all probability, I stood more of a chance getting shot stumbling onto some hillbilly’s still.

It was during breakfast on a sunshiny spring morning, shortly after the aborted break out, when deputy dog came by and told me to grab my coat. Now get this: I had gained eight days credit for good behavior.

Although a knight errant of the cinder trail was always alert, sometimes incidents occurred that could never be foreseen. - I certainly never suspected by midnight on a hot-hot express, memorable events would cure me of one dangerous road habit: 'deadheading' a train accustomed to taking water 'on the fly'.

The deadhead was usually an unheated half-coach half-baggage car coupled to the tender of the engine. If ever the occasion should arise, the car was used for baggage or passengers; otherwise, it rode the rails empty, thus: deadhead. It was murder riding those deadheads, but some guys rode nothing else.

To become a member of the deadheader's exclusive club, the initiation was rugged, but the prestige was great when around a jungle camp fire, with everyone knowing you had attempted and successfully completed such a daring feat. I rode my first deadhead one midnight out of Bangor, Maine's Union Station to Boston. Luckily for me the door was unlocked on that empty coach, but no heat. That midnight ride in early May gave me chills that had me shivering for days after.

The weather was warmer, at least, as I headed into Chicago, the evening of that August day. Whenever coming to the outskirts of a large city, the engineer would often be signaled to slow down or stop before proceeding the next mile or more to the railroad yard. Any hobo riding who was unfamiliar with the yard layout or with such variables as third rails and bulls, should do the bright thing: unload and leave the right-of-way as soon as possible.

To ride too deep into a strange freight yard without knowing where to disembark, especially at night, could lead one into a frightening or even disastrous situation. Riding in, ignorant of the environs, was considered a cardinal sin to a self-respecting hobo, as it could mean the difference between being free or being dead! It was deemed imperative to memorize any important bits of information gained in idle conversation at the previous jungles. As a loner, I missed access to much of this information and many times had to rely on my feet for a , speedy exit.

I had walked through Chicago a few months earlier, and so there I was again, riding alone on the C. B. & Q. (Chicago, Burlington & Quincy R. R, ), heading right into the heart of Chicago, late one evening.

With a few bucks earned working in the wheat fields of the Red River valley, I was going east. If the mixed freight ever slowed down, I planned to ditch it, as I had the dreadful feeling it was going further into the yard. The wind wasn't right to bring the aroma of the cattle pens, so my exact location seemed more of a mystery. There were tracks on either side of me with standing, engine-less freights, while passing on the opposite side were endless strings of gondola hoppers, plus loaded reefers leaking ice water, pulling east. Occasionally a passenger train would go by, its destination unknown to me.

The iron brakes creaked against the wheels in the dusty air, and as I nudged the box door open, the cars came convulsively to a full stop. Mingled with the muffled din of the yard ahead were the distant sounds of hogger's signals. Looking outside, back and forth over the dimly lit area, a 1one figure was seen running across the

tracks. When I hollered, "Which way is out?" he motioned to follow, and we ducked in and out between cars, crossing tracks, then let a passenger roll by until the way was clear, to finally arrive at an overhead bridge.

Reaching the safety of the street in our coal-dust blackened clothes, we walked until a diner was found. When I offered to pay for his meal; my friend replied,

"Save your money, kid, I pay my own way. " He mentioned he was going east and would show me the fastest way to shake the 'Windy City'. For a chance acquaintance, this guy had brass, and it would prove interesting to explore his modus operandi, so I thought, The meal hungrily consumed, we rode the bus to within a few blocks of the LaSalle Street Station, on Van Buren Street.

We walked into the huge station where a glassed-in timetable showed the Motor City Express would leave at 11:59! That's all my friend needed to know as I followed him around the busy terminal, going past loading platforms and baggage cars, to search out New York Central’s idling engine, which, according to schedule, wou1d be pounding the rails that night.

When we were satisfied that the deadhead was coupled on, we back tracked our way out with me expecting to be nabbed for trespassing at any moment, My fellow traveler took the risk very calmly, Back at the station cafeteria, we consumed more pie and coffee and waited out the late August evening, watching the hands of the station clock creeping up to eleven fifty-five, With four minutes left of the countdown, we were on our way to track #4!

Surrounded by the confusion of a large railroad station, nobody gives much thought to passersby. We were greeted only by a few curious glances from busy baggage men near the platform of the train shed as we proceeded to the other side of the engine. Just then the conductor’s high sign to the hogger was recognized, and the idling engine came to life in a sudden burst of power, The tallow pot watched us climb the ladder of the locomotive's tender to board the deadhead. The moving passenger was on its way.

My new-found companion tested the door at the forward end of the empty coach where we were perched on a narrow iron ledge, now concealed from view of the engine by the tender in front of us, and enclosed on two sides by canvas skirting which ordinarily sealed the gap between coaches from dust, smoke and the elements. The door was locked! By now, we were gathering speed; the terminal was left far behind, and steaming cinders mixed with coal smoke choked and blinded us while the express felt its way along the myriad of tracks leaving the suburbs. I was advised to stay alert as the engine would take on water in two hours, thereabouts.

We seemed faced with eternity, rather than a few hours, considering there wasn't much room on that ledge between the flanged canopy, and only a doorknob to hang on to. The hot-shot express wasn't wasting time flying over those rails, kicking up dust and debris from a roadbed that was sweeping by just below us in a blur of ties.

It was long after midnight, and the small towns kept looming up, only to disappear fast, their crossing signals flashing and bells ringing loudly, the sound to fade away as we zipped by. The crazed locomotive with a full head of steam raced down the track, with the hogger rejoicing, having all-clear signals.

The carbon steel wheels beat a ceaseless tattoo on rail joints, lulling off to slumber the fortunate ones in the Pullman sleepers. It was past boxcar bedtime for one penitent traveler named 'Bones', hanging to that exposed deadhead. As I was meditating in retrospect, wondering whether I had ever spent a worse night on the road, a sudden mixture of water, coal dust and cinders was signaled as the express eased underway again, scarcely spilling a drop of any early riser's coffee. The aroma of it wafted from a chef's open pantry window as the last Pullman coach inched by, silently.

In the murky half-dawn, my friend continued to hang on to the 'Motor City Express', to vanish leaving only a memory of that nightmarish ride. I walked the track until I came to a section hands utility shed and lean-to where I dropped exhausted, only to awaken when the bright rays of the morning sun warmed my damp clothes.

Boarding a train that guzzles water on the fly in the dead of night isn't an advisable way for a timid soul to draw a shower bath. Coal dust, washed with tears, had streaked down my face and left my eyes smarting. If the rest of me should ever smarten up, the chore of washing could continue, so I thought, as I walked beside the rails, counting the ties on a crushed-rock roadbed.

MAINE

Joe Curtin

Spent 45 days in jail in Spencer, NC

Recently went to look up record: The only thing I questioned was the word “harmless” on the citation. I have had some lively spots in my life for a guy who was harmless.

RR hobo nicknames:

EP&SW El Paso and South-Western = “Eat Plenty and Sleep Well”

D & RGW Denver and Rio Grande Western = “Drink and Rest Go West

SP Southern Pacific = "Small Pay"

AT & SF Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe = "All Tramps Sent Free"

MAINE

Tom Schenk

“I lived through the Great Depression and I traveled through 47 states and think back on the hobo years as actually the golden era of my life.

I really found the American masses to be kinder, more helpful, more down to earth human beings than they have been since…

American masses running scared because of the recession are like children crying because their toys are broken.

I was a deluxe hobo. I did it because I wanted to, not because I had to.”