MICHIGAN

Carl Baird

Father was minister of the Lutheran Community Church and founded the Lowell, Seattle Hooverville

He worked with a group of community people to set up what came to be known as a Hooverville down by the tracks. There, anyone coming in from the freight trains could get (1) a shower and “de-lousing” (2) their clothing laundered (3) three square meals (4) a night’s sleep on a clean bed.

Each person could stay 24 hours and then they had to move on. In charge of the operation was Slim (I never knew any other name), who came off a freight train himself and who walked with a limp because one knee was stiff and bent. He saw to it that the system worked and he was respected.

“I’m kind of proud of the memory.”

MICHIGAN

Delbert Esche

I boarded a freight in Salt Lake City. At the first stop where the locomotive took on water we dumped out our good mountain spring Salt Lake City water because it was warm from the desert temperatures. The water from the standpipe bubbling near the railroad water tower looked so cool and refreshing. We rushed back on the train to discover our new supply was tainted with a bad sulfur smell and taste.

The experience was repeated at the next water tower and the next all the way to the coast. The water situation got worse and worse, until finally after coasting down a long grade and onto the Pacific flats somewhere near San Bernadino, Calif –“San Berdo,” we bums called it – the train came to a stop alongside an irrigation ditch.

From the train, a hundred people descended in an avalanche, most of them to fling themselves belly down on the ground to drink out of the irrigation ditch, the first non-sulfur water they had had in days.

MICHIGAN

Dell Ahlich

16, 1938

Bummed bakeries for “stalies” and butcher shops for “ends”.

In Billings, Montana there was a restaurant of sorts in an abandoned railroad car – it was operated by a couple of bo’s and the china was chipped or otherwise damaged dining car china. They sold stalies for 1c, coffee for 2c – the clientele was all hoboes. It was in a railroad car graveyard on the edge of the yards in Billings.

There was a bad railroad dick named Humpy Davis in one of the bigger yards in Minnesota, noted for having a heavy hand with his nightstick.

Traveled with a couple of guys from Minnesota who were going on to Butte, Montana to work in the copper mines. We were catching a train on the fly in ND when one of guys lost his cap as he caught the ladder. A brakeman with heart picked up the cap and ran with it up to the ladder and handed it to him.

MICHIGAN

Denzil “Denny” Stephenson

14

Saw restaurant worker knocked down by car. Went and got the man’s job.

“Stay out of the ‘tall stuff’ (= affluent neighborhoods), they’ll call the law on you.”

Poor neighborhoods were almost always most sympathetic to young drifters since we had a great deal in common

Hoover blankets were newspapers wrapped inside clothing to help stay warm enough to sleep. To ‘Carry the banner’ meant to stay awake, walking all night to keep warm. It was common to ask for newspapers at barbershops late p.m. to use to keep warm at night.

On farms from Michigan’s cherry orchards to California’s grapes, peaches and Washington’s apples.

At Merced, California when growers reduced pay to a starvation point, a strike resulted in violence, with sheriff deputies clubbing and injuring men, women and kids.

At the same camp, refrigerator cars called reefers stood empty and were occupied by workers until the strike was called. The IWW was the organizing group and vicious fights were common, since that Union was said to be Bolshevik, communist and gang-related.

They did have wide-eyed speakers, well versed in rabble rousing and it was sometimes very dangerous even to have an opinion, either for or against the strike, depending on who was listening at the time.

MICHIGAN

Dewayne Evans

17, 1940

“I was ready to face the world with my $27 and all my worldly possessions in a small athletic canvas bag. I even took my high school diploma and Bible.”

Sights?: Viewing the Royal Gorge Co. from the top of a reefer at night./ The painted desert of New Mexico at evening time./ Mt. Albert near Leadville was my first snow covered and most beautiful mountain.

The Okies and Arkies were all good hard working people. They didn’t have much education. They treated me like a king because I could read and write.

In Pampa, Texas I applied at a supermarket for a sacker job but was refused for lack of having a social security card. I sent to Austin for one and received it. By the time I got it I was fed up with the panhandle of Texas. It was too hot, too dry, no grass, no trees, just oil wells and carbon black plants.

I bid my old buddy and classmate goodbye and headed for Colorado.

MICHIGAN

Edward Kale

I was 16 years old at the time and weighed 160 lbs on account of malnutrition. I did manage to throw a rotten tempered railroad detective off a freight train one time.

MICHIGAN

Gordon Bredersen

17 and 19, joy riders and to work

“We hooked a ride thinking we were going to California but ended up in Seattle.”

Navy beans and cracklings

Walla Walla, Washington: An unbelievable hobo town. The hobos had made houses out of flattening five gallon cans. Walls, doors and roofs were all shining flattened cans. They even had attached numbers so they could receive mail.

“I have a clear feeling that a black cloud constantly hovered over my generation but at that time I luckily didn’t know it."

MICHIGAN

Merlin Powers

15, 1939

Coming into Eads, Colorado, man was telling us how to look out for detectives. He stepped between drawbars when speed of train changed. Foot was crushed flat to above ankle.

Dust storm hit Eads the day after we got booted off that train. We had no shelter and tried covering our heads with our jackets to protect our eyes and so we could breathe.

MICHIGAN

Patricia Schreiner

I grew up in a house which was one block from the Michigan Central Railroad, and two blocks from the New York Central Railroad, in the small collage town of Ypsilanti, Michigan.

There were many hoboes on those trains, and many of them came to the houses in our neighborhood to beg for food.

Summer saw them wearing the most tattered clothes I ever saw, and there were lots of bare feet.

Winter saw them wearing a jacket over a sweater, tattered trousers, and shoes full of holes, and the soles flapped loose as they walked. Some wore overcoats that were ragged, and the lining hung below the hemlines.

Most of them had no boots on their feet - only the loose-soled shoes that flapped. On their hands, most had gloves, only the fingers were all raveled out.

"Put your pride in your pocket and your hat in your hand."

These men were hungry, and they were dirty, but not one of them ever behaved in any but the politest manner, and all they asked for was something to eat.

My Mother, and all the other women in that neighborhood, always gave them food, even if it wasn't always much more than a sandwich. The sandwiches always disappeared in a big hurry, too.

There were never any questions asked these men, nor was any information ever given. They never asked to come into a house, and most of them left as soon as they were given the food they asked for.

My Mom kept her wash tubs on a bench just outside the back door. She would usually tell these people to move the tubs and sit for a few minutes. Not many of them did.

I can also remember one cold, snowy, below-zero day when a hobo came to the back door. Mother had just heated up some tomato soup to go with our sandwiches, so she grabbed up a bowl and filled it with soup, then proceeded to tell the hobo to step inside the door to drink the soup, and warm up a bit. He refused to do so, and we all felt so badly because he looked half frozen.

He stood just outside the back door, spooned up the soup and ate the sandwich Mother gave him, then, as he left the empty bowl on the kitchen floor, he quietly said, "May God always bless you, Madam."

Mom had tears in her eyes as she watched him walk down the back alley to the railroad tracks.

There was one lady in the neighborhood who refused to feed the "lazy bums." But everyone else did. They were concerned not with the fact that they might be lazy, but with the fact that those men were hungry, and they needed to know that there were people out there who cared.

The women all said that if one of those hoboes was their son or husband, they would like to think that some housewife was giving him a bowl of soup or a sandwich.

The Depression Days were hard on a lot of people, but at least we had a roof over our heads, our Dad had a job.

Those days taught us a lot about how to get along through the rough times.

We survived, and I like to think that some of those gentlemen, those "Knights of the Road", have survived and maybe one of them had something to eat at our back door.

MICHIGAN

Peter Pultorak

18, 1931

I hoboed and off for eight years: It was hard traveling across America from one state to the next.

The second day after I left to go to Florida, I met a tramp who got to telling me how to get by without money:

“Put your pride in your pocket and your hat in your hand and tell them like it is.”

MICHIGAN

Rosemary Macheske

1934

I remember Dad didn’t work for three years. Families moved in with us. “Lost” their homes, everything. Fear was their daily companion. Mom cooked every meal, canned 500 quarts of fruit.

Guys off freight trains begged for food. Mom fed them. Table and chairs in back yard. Gave them bags of food for family.

Mom never quit. Pray she did. Helped us grow in faith and hope for a better future. Self-control is needed in all humanity.

MICHIGAN

William Vandenberg

Summer of 1935, 17

While riding through Iowa something caught my eye which I hadn’t noticed before. I saw entire fields which looked black, as if a flaming fire had burned everything growing on the land. It was the sun, dry weather and over 100 degrees temperatures which caused the land to appear black and burned.

MINNESOTA

Chester Swanberg

A boxcar we were riding was set out during the night in far end of the railroad yard in Pasco, WA. We were all sleeping on the floor. The next morning we discovered we were locked in. We were so far in the yard no one heard us to let us out. I was the only one of us to carry a pocket knife. We could see by the bolts in the door where the latch was. I started whittling with my knife and finally cut a hole through 1 ½ inches of wood large enough to reach through and unlatch the door.

Haystacks were a good place to sleep. Rain does not penetrate a haystack and the grasshoppers and crickets were friendly little critters. I slept in haystacks many a night. About ten minutes of digging into the haystack makes a good bed. Quite comfortable with about two feet of hay under and 10 feet on to. Crickets would wake you with their chirping in the morning.

What a sight to see those perfectly shaped haystacks out there in the field like fresh baked giant size loafs of bread.

I am a retired locomotive engineer.

MINNESOTA

Dick Gavin

16, 1934

Wanderlust

Riding descriptions

Caught riding the steps of a passenger train.

My friend advised me that if we could not board the tender or the ladder on the diner, to catch the vertical hand hold adjacent to the steps, and swing in under the step platform. We were determine not to be left out on the prairie.

As the train got under way, the conductor and fireman walked and ran along side the train until they had to get aboard. As soon as they boarded, we ran for the train which was picking up steam. We were unable to catch either the tender or the diner and both ended up catching the vertical hand holds on one of the passenger cars, and swinging in under the steps, which presented a somewhat cramped position.

A short time later, the platform above my head was lifted up, and there stood the conductor. He told me to come up into the train, and had me sit down in a coach seat with my friend. He then proceeded to give us a 1ecture on the danger of riding the steps as we had done.

The train frequently hit stray cattle, and their bodies had been known to knock the steps off the train. He advised us to stay off the passenger trains and that we would be put off the train at the first stop. We rode inside all that afternoon across that flat country until 10 o'clock that night when we arrived in the town of Dickinson, North Dakota.

MINNESOTA

Elmer W. Beckman

Born 1913

I lived in the small village of Holdingford in central Minnesota. Left home to seek adventure and get away from what I thought was a domineering family.

Desperate for any kind of job, a friend suggested we hop a freight train and go to the state of Washington, where there were jobs picking apples. The nearest railroad was at Little Falls about 20 miles away. By the time we finally left there were five of us, all teenagers.

The only money we had was about $10 between the five of us. We did get to our destination, which was Underwood, WA.

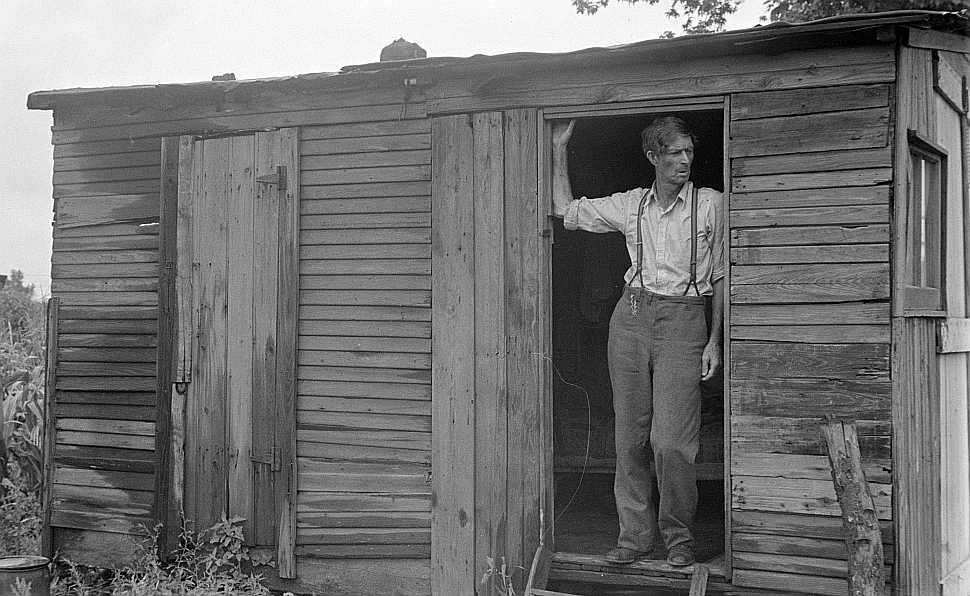

The job paid the unbelievable sum of 17 ½ cents an hour. We lived in little shacks that had an old wood stove and a broken down bed. Only running water was a faucet in the yard. The toilets were outhouses about a block away in the woods. Fruit was free and plentiful including apples pears peaches and grapes. With that exception we lived on macaroni and beans plus meat once a week.

MINNESOTA

E. W. Beckman

We soon learned that trains do not got directly to any long distance place but are dissembled at certain points along the way. = Division Points

Some of the railroad bulls were extremely sadistic, beating anyone within reach with their batons. The one I remember vividly was Pasco Slim in Pasco, WA who was known from coast to coast and feared by all.

Most remarkable was the intimate contact with people from all walks of life, each with a story to tell of why they were in such dire straits. Regardless of their prior social status, as hobos there was absolutely no class distinction or one-upmanship among them. Any disagreement was usually verbal, but in case it resulted in a fist fight no one interfered if it was a fair fight.

It was a time of my life that I would never like to repeat but an experience that governed much of my life after the Great Depression. My entire perception of people changed and I did learn to accept people at face value.

Also discovered the difference between worldly knowledge and book knowledge, and that the latter does not teach us to survive under adverse conditions. Seems to me that a one subject lifestyle leads to a rather dull existence.

In spite of being years away from the road I still get a nostalgic twinge when I hear at train whistle and never get impatient at a train crossing.

It allowed me to have a bit more compassion for the not so fortunate and to lead a very conservative life style.

MINNESOTA

Erwin Bjorngeld

The 30s were the restless years. Thousands were riding freight trains in all directions. Some were looking for work of which there was very little, but it could be found if you were in the right place at the right time. Others were riding just for the enjoyment of it, and to some it was a way of life.

At every railroad junction the government had set up soup kitchens. Anyone without visible means of support got three meals or a 90 cent grocery order. Then you moved onto the next junction about 300 miles down the line.

To all the tired and weary who traveled by side door Pullman – boxcars -- barns and haystacks became temporary abodes. No reservations were needed and rates were reasonable. Jails also served as overnight lodgings for hobos and wandering vagabonds.

Most of these were respectable people, not to be called tramps, bums or vagrants. Oh, some of them had to resort to begging if they wandered off the main line where there were no soup kitchens but for the most part good people.

Most conversation among these knights of the road was:

“Rosie hasn’t done much for us yet.” “I wonder how long it will take FDR to end this depression?” “Frank has been in office three or four years and I haven’t seen any change yet.”

Traveling around the country on a freight train was known as being “on the bum.” It did give me so much to remember, the Rocky mountains, national parks, the Cascades and the Pacific Ocean. The view from the huge box car doors, especially in the mountains was breathtaking and unforgettable.

We didn’t have the luxury of reclining seats, mostly we sat in the open door, but the cars were large and roomy enough so one had the freedom to get up and walk around. No there were no snack bars, but from the balloon (backpack) we carried around we could always build a tasty sandwich.

For sure one met a lot of interesting people from all walks of life. Some became special friends. Like Gene Lucas, I’ll never forget this guy. A handsome man in his thirties dressed mostly in western clothes, a deaf mute.

The first time I met him was somewhere in Washington. Most of our conversation was through writing notes. I think I met him at every big town between Seattle and Fargo and we became very good friends. I rated him as a great artist. He always carried a tablet without ruled lines and a lot of pencils. He would go into a bar and draw a picture of the bartender who would give him a couple of bucks for the drawing. Mostly he drew western scenes equally as good as Charley Russell’s.

In June 1934 Oliver Running and I with our balloons on our back strolled into the jungle of Williston ND and joined the masses – the unemployed who wandered around aimless and in no hurry to get there. We were also looked upon as the lower social order.

Thus began my travels that were to last through three summers and many thousands of miles.

A bindlestiff was what everyone was called who carried a blanket in a bundle. Stiff refers to the awkward way a guy moves around with a balloon in his back. Bindle is hobo slang for bind. You bind your blankets into a bundle. Stiff refers to the awkward way a guy moves with a balloon in his back – not with ease and grace. And believe me some of these balloons were huge and almost perfectly round. I saw some of these guys back up to a boxcar door and roll their balloon in.

Impressed for fire-fighting job in the Rockies.

“When we pulled into West Glacier, a forest ranger met the train. He told us he was there to recruit about 20 young men to fight a forest fire about 15 miles south of there.

“I wasn’t exactly happy at being drafted into this hazardous duty, but then I thought “Hey, this is high adventure” and how many chances does a guy from the prairies of North Dakota get to fight forest fires? We were loaded into two dump trucks and hauled out to the fire.

He replied. "Don’t worry, you guys are going to do the mopping up. Each of you will be issued a spade, hatchet and broom. Most of the work will be done stooping over so I hope you have a strong back. The pay is 25cents an hour and the foreman gets 40 cents.”

MINNESOTA

George De Mars

“My story covers only a four-month period but it’s worth it. It began shortly after my special hero Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated president for the first time. Bless him.”

“After graduating from high school in 1932, I accepted a job working on a farm for $25 a month for the summer months and $3 for the winter months. I became so discouraged at these wages that I another friend decided to see some of the world together. In February 1933, we began from Minneapolis, 20 degrees below.

“The first night we shared a bottle of moonshine to keep warm in a boxcar traveling toward Illinois. Arrived in Savannah Illinois. It was raining there. We went bumming for raincoats and each received one. Our destination was Las Vegas, Nevada but we were in no hurry to get there.

“Traveling through Bakersfield, CA , a black man and I were each riding between cars hanging onto the steel ladders. A boy threw a fair-sized rock at the black man, he dodged it, but it hit me in the shoulder. Thankfully I didn’t lose my grip on the ladder.

"Even in those days racial prejudice was noticeable. Blame parents for this. My parents taught me right because I had very little prejudice in my soul. Overall, people in general, in those days had a lot of love for one another.

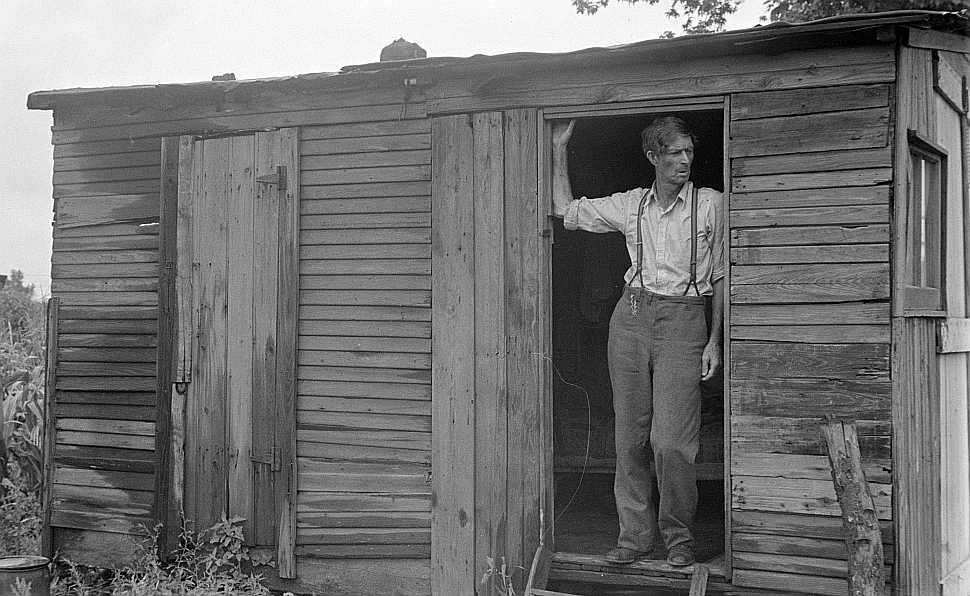

"Arriving in Albuquerque, on a cold Sunday morning and feeling very hungry. The city, the scenery was beautiful; but we entered a city that was foreign to us. We saw nothing but poor Mexican people and donkeys. Finally, we spied a café. I had enough for a breakfast, but no one spoke English. Finally we made the cook know what we wanted by drawing it out for him. A Mexican celebration of some sort was going on; beautiful music and dancing. The city was small at this time. We stayed through the day and enjoyed the way the people lived.”

“A bad person to me was the barber who cut my hair on St. Patrick’s day in Los Angeles. Haircuts in those days were only 20c. Anyway this barber must have been Irish and celebrating too much, unknown to me.

"Wow, what a haircut I got! Cuts all over the back of my neck and a shingle type job. My pardner and brother sat looking at me and laughing. When they saw how angry I was getting, they got on my side and made the second barber patch me up and do the job over.

"I hated spinach. One day when I was begging at a house for a meal, the woman came out with a large platter of spinach. I was so hungry that I ate it all, and I’ve loved eating spinach ever since.

"Franklin Delano Roosevelt was my all time hero when he introduced the CCCs. I served 2 ½ years in the Finance Office typing out the allotment checks that went to parents, plus figuring out the payrolls for all the CCC camps in Minn. The pay was not great but it took a multitude of young men off the road and kept them on the straight and narrow.

"We had good food and clothing and comrades. We were under army discipline and made good soldiers when it came to WW2."

Rest of life? “It made me a better person. I sure grew to understand other people's problems. It also taught me the goodness of other people.

While on the road, I gained 20 pounds, from a skinny 115 to 135 pounds. I had a hard time to learn to sleep in a bed when I got home. I had to sleep on the floor of my parent's home the first few nights. The comfort of the rolling train and the clackety clack of the rails was missing, only after the third night or so was I able to stand to sleep in a bed again.

I learned to appreciate the beauty of America, of the plains, the mountains, and the wonderful people in it."

MINNESOTA

George Sweeney

Freight conductor, now 92

Recalls thousands of hobo “trespassers”

“Conductors and brake men were told to ignore them. We never ordered them to leave except for drunkenness or causing trouble.”

MINNESOTA

Jim Mitchell

16 to road

Farm foreclosed because of dust bowl

At school people called him "welfare freeloader"...fought with schoolmates, hit teacher -- expelled.

Dad was on the street x jobless/ mom took to drink... remember father crying when he lost job

"Father was a psychological casualty of undeclared war"

”To put the Great Depression into proper perspective one must first bear in mind that most of the parents of my generation were fresh off the boat. To them America was opportunity. Working in a factory was heady stuff for an immigrant who, but a few months ago left a homeland where poverty and destitution was the norm. The world was his oyster. All he had to do was work hard, obey the law and go to church on Sunday, and he had it made. Then!

All of a sudden the bottom fell out. Why? No one had the answer. Many thought that it was they who had failed. All too often one would hear, “There is work out there if only they will go looking for it.” Being on the welfare rolls was the ultimate indignity. To this day there are those from my generation who refuse to admit that they needed a helping hand.

Basically, the CCC was set up to give help to boys whose folks had fallen on hard times. We never fired a shot. In fact we never shouldered a gun. Nonetheless, it was one of the finest hours in the history of the United States Army: administration of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Today, in many ways, is a mirror image of those fateful days; crime rising and thousands of young people footloose and arrogant. Young people in the 30’s were sorely in need of guidance and direction. The Civilian Conservation Corps filled that void.

I know, first hand, the benefits of serving in that effort. In those fateful years I was but a boy in my teens, a time that should have been filled with hopes, plans and dreams. The luck of the draw and global events over which I had no control put my air castles on hold. Although three and a halt decades stand between me and those dire days I shall be forever grateful for the only truly national service program in which our nation was ever engaged.

Taken from the steamy streets of cities in economic turmoil we were transplanted to camps where, in trade for a dollar a day, bed, board and clothing, we renovated streams, controlled timber disease and fought forest fires. In the latter our efforts held our national timber loss by conflagration to the lowest in history. I shall never forget that 74 of my forestry comrades gave their lives in achieving that enviable record. Sadly they were never eulogized nor posthumously awarded medals. But as surely as any man gave his life in the service of his country these men, too, served in a noble cause.

Today we can visit with pride the hundreds of parks we built. In a recent. visit to Itasca State Park, in Minnesota, a forest ranger said, “Without the CCC it is doubtful that we would have the park system that is in place today.”

Perhaps that is why we who served as “conservation commandos” look back with pride on the enduring contribution we made to our country. One twenty year leatherneck, quoted in Jim Klobuchar’s column of the Minneapolis Star Tribune, went so far as to say, “My two years in the C’s meant. more to me than my twenty year tour in the Marines.”

In camp, under the guidance of solid military men, we learned that camaraderie and esprit de corps was not so much verbiage but solid values that gave meaning to our lives.

I shall never forget the day in the Fall of ‘34 when I received an object lesson in “community of interest”.

Two hundred twenty Depression weary boys were shipped north from Fort Sheridan. On arriving at camp, my first job as a tenderfoot from the concrete canyons was to haul tamarack poles out the muck and mire of five hundred years of loon dung. The day started with our getting wet to our belt. buckles. It never got any better. That night. we slogged back into camp, bone weary and whipped. As we passed the dispensary one Lt. Kuehl, the camp doctor, standing on the steps, barked “You!” I looked at him and he nodded. “Yes, you. Come her

I recall quite vividly that the last thing I wanted was a reaming by a shavetail. So, with an outsize chip on my shoulder, I strutted over to him. For a moment he looked me over and then in a concerned tone of voice, asked, “Where are you working, Son, and who is your crew chief?” I told him and our “leader” received the most devastating reaming I had ever heard. Woven into the tongue lashing was counsel on leadership and responsibility for the welfare of his men. His final edict was that, “No one is to work on the tamarack detail unless he has hip boots.”

It was a solid object lesson in comradeship and esprit.

Duty and discipline became part. of our lives; values instilled by the firm hand of military men who guided our lives. As boys we sometimes lost sight of these virtues. An evening of splitting firewood, after a hard day in the woods, was all we needed to get us back on track.

The benefits of camp life were manifest in many ways. Scrawny kids filled out and returned home hearty and healthy. The financial aid we provided our families made men out of boys. Of equal importance were the intangibles.

It gave us a new understanding of our country and what we built gave us faith in the future. Kids from the teeming cities met and worked side by side with farm boys. Country boys, in turn, came to know and appreciate the rich ethnic variety in America. All of us left camp with a better understanding of the colorful diversity of our country.

During the perilous thirties Judge Broude of Chicago estimated that he CCC was responsible for a fifty percent- reduction crime because “....it. took boys off the streets and inculcated in them a sense of values.”

Following our tour of duty, filled with new hope and vision, we returned home. From our ranks came the full register of professions and the driving force of industry; men who manned the mills. Then, when the Axis threatened all we had worked to preserve, we stood ready to serve.

Today, millions of boys and girls could reap the same benefits as we, if only we had the courage and vision to implement a new version of the CCC.

MINNESOTA

John Wayne

Hitch-hiked to ND in June of 1934. Rode a freight to Missoula, Montana, where I was rolled in my sleep and lost what money I had.

I was raised on a dairy farm so it was relatively easy for me to find work. Stayed till June 1935. I had temporary jobs on eight different ranches. My highest pay was $1 per day and 2 or 3 paid $20 a month.

August 1938- May 1939 various trips.

“I remember vividly seeing whole families on the move. I remember trains with over 200 people aboard. I have memories of 1500 transients in the jungles of Laurel, Mont.

I saw at least two people die of accidents. There were several types of people traveling. Migrant workers, young boys, young girls 12 to 15, traveling in groups of five or six. They all had one thing in common – no job – no money – no hope.”

MINNESOTA

Lucille Schroeder

I was a rural teacher in Brown County, MN near Springfield.

We had bums who would break a window, get inside school and drink all bottles of blue ink for alcohol content. I still have scars on my hands to prove it.

MINNESOTA

Oliver Gronsberg

I spent my 17th birthday, August 8, 1932 by walking into the town of Missoula and splurging on a malted milk shake. I remember distinctly it was a root beer malt. I then headed back to Minneapolis. I had an old black leather jacket with a poor lining. There were no empty box cars and I had to ride on top. Those nights in August were awful cold going about 70 miles an hour. Tried getting behind a refrigerator box car cover about four inches thick. Cold? I never was so cold in all my life. That leather jacket like a shield of ice.

MINNESOTA

Reed Lawson

I was too embarrassed to ask for work or food. When I first started riding the rails, I went three days without eating. The guy who was showing me the ropes kept asking me if I was getting food and I kept telling him I was because I was too embarrassed to admit to him I didn’t have courage to ask.

In many ways there was more equality between blacks and whites than there is now. We were all trying to survive. It was a supportive environment with one looking out for another.

I know that material possessions can be gone in an instant. They are to be appreciated for making life easier, but they do not define life’s values. I know that a person can be down and out without being bad or lazy.

When I married I emphasized to my wife that we would give food or what we could to anyone who came to our door.

MINNESOTA

Robert Snow

I recall one of the hobos vividly. He was probably in his 40s and told us he had been riding the rails since the 1929 Crash.

On this trip he planned on riding west to a warmer climate as winter was coming. He wore at least three pairs of pants and a like number of suit coats and/or jackets. His shoes soles were parts of auto tire treads.

We concluded that he must have been just about the laziest man we had ever seen. He had a cold and a very runny nose, but he couldn’t be bothered with continually blowing his nose. Instead, he would tear up a rag in small pieces and stuff one in each nostril. Periodically, as needed, he would replace one with dry pieces.

MINNESOTA

Russell Morrison

14, 1936

with 18 year old

Runaways from Staples MN to the west

"I took a dissembled double barrel 12 gauge shotgun and some fishing equipment.”

North Dakota: In addition to the heat, there were so many grasshoppers in that we could not stick our heads above the sides of the car without being struck by a cloud of grasshoppers.

Nineteen hundred and thirty six was the year of the terrible drought with record high temperatures. When I looked over the barren land without a tree in sight I thought it must be the worst place on earth. It’s probably unfair to judge North Dakota by that first impression, but I’ve passed through many times since without any desire to pause.

There were no empty cars so we were riding on top. We buckled our belts through the catwalk to avoid falling off when we went to sleep. At 65 miles per hour, without shelter, it was very cold and would get worse when the sun went down. There were other riders on the train, and a middle aged man came over to me and asked if I had a coat.

When I said that I didn’t he told me in a rather stern voice that the next time the train stopped I should run to the nearest house and ask for a coat. When I told him I couldn’t do that he took off his jacket and tossed it to me saying he would get one at the next stop and went back up the train.

There was a grain field next to the tracks and the grain had been put up in shocks. We decided that we would each get into a grain shock hoping that it would keep us warm until the next morning. We soon learned that it wouldn’t be warm enough so we started looking for some other way to survive the night. There was a lumber mill nearby so we decided to check it out. There was a cone shaped silo and I’m not sure what it was used for, but we discovered that if we stood against it we could feel a little warmth coming through, so we spent the night standing up against the silo.

MINNESOTA

Selby Norheim

I was riding a freight that was stopping in Laramie, Wyoming. The door was almost closed, which was the way I wanted it, but when the train stopped someone started to slide the door open. I figured I might be in trouble. My fears evaporated when I noted that the man outside was a brakeman.

He looked up at me and asked, What do you do beside bum around the country?

I answered, "Look for work, sir."

He asked, "Do you drink?"

I said, "No, sir."

"Well," the brakeman said, "I'm really looking for someone who drinks." I thought about that for a few seconds and said, "I'll drink if I have to drink to get the job, sir."

He laughed and then explained that some years back a fellow came through Laramie with four silver foxes but no money. He needed a place to raise the foxes and offered a pair to the brakeman if he would help him. At this date the brakeman now owned 21 foxes and was in the process of building pens for them.

For the next two months I dug ditches in which the fencing around 10 pens was buried to keep the foxes inside. I lived in a small shack and was given a .22 rifle with which I was to keep the mountain lions away from the foxes. Happily, no mountain lion showed up.

MINNESOTA

William Rom

At age 16, and with $3.50 burning a hole in my pocket, I was determined to see the Chicago World’s Fair. Chicago was 600 miles away from my small home town of Ely, tucked away in northeastern MN “at the end of the railroad."

At Milwaukee…I made a leaping dive for the ladder up the locomotive water tank .. I swung like a pendulum with only a hand hold and struck the head of a bolt on the locomotive, cutting my thigh through my pants and long underwear. People were gaping at me as I clung on for dear life as we picked up speed and passed through the residential district. Alas my buddy (with most of the money) never made it…

As we arrived in Chicago cops ran for the train as we scampered down the opposite side and disappeared in a slum district, where we washed up at a gas station, and my CCC friend separated to go his own way.

I hitched a ride to the north gate of the fair and sat on the steps of the Field Museum all afternoon, hoping my buddy would pass by but no luck… Little did I know he was waiting for me inside the gate.

Next day, I took in the fair which cost all of 25 cents and visited all the free exhibits.

My only regret regarding the trip was that I couldn’t afford any of the exhibits that charged a fee, including Sally Rand. And she only charged 10 cents!