INDIANA

Algie Ennis

13-year-old left homeBorn Dec 12, 1921,

Not finishing the third grade, I left home when I was 13 years old. I worked on farms or in the swamps cutting timber for 50 cents a day. Bayou Swamps of Louisiana

I started riding freight trains in the fall of 1935, for three years.

In February 1936, a friend and I caught a freight train. I had no underwear on and a light jacket.

About 50 miles north of Jackson Mississippi, I was freezing. We were in an open coal car. I set the car on fire to stay warm or stop the train.

INDIANA

Bill Eberle

I arrived in Topeka in the early evening just as it was starting to rain so I decided to go to the jail for the night…

Next morning, someone came to the cell door and yelled, "Line up over here"

They marched us down the street a couple of blocks to a lot filled with cut up tree trunks. The man said "Start chopping!"

So we did. We must have chopped for half an hour when he said, "Line Up" again.

They marched us another block into a building that was set up for breakfast. We sat down and had a real good breakfast.

Then he said, “Get on your way.”

INDIANA

Billy Watkins

As I was riding through Texas, a baby boy was born to a young girl in a box car that I happened to be in. A much older man, her grandfather probably, was with her.

There were three others besides myself riding along with them. An old "bindlestiff" (one who carries extra clothes in a bundle on his back )offered a clean white sock to tie around the baby’s middle.

Named the baby, Toyah, after the town that the train would be stopping at next and they were taken away by ambulance. I remember that they wouldn’t let the old man ride with them. Often I have wondered where the baby might be today.

Another time in Colorado, I got into a box car at night, unaware that a dead man was also inside; learned this later when I accidentally stumbled over him.

This was a terrifying experience. I stood in the doorway for miles, trying to think what I must do. The train did finally slow and stop to take on water; immediately I jumped out and ran as far and as fast as I could into a field.

There I waited until the train pulled out, by that time it was beginning to be daylight. I helped a work crew sort bolts and nuts for two days, for my meals.

A train stopped the second day for water, I got on it and got off at Pueblo, Co., where I overheard someone saying that a fellow that was found on the train had been stabbed in Elko, Nevada.

Somewhere in Oregon, when I climbed from a refrigerator car, there before me was the big beautiful Pacific Ocean, the first time to see an ocean. I was transfixed for several minutes, just watching those big waves roll in.22-year-old woman rode with husband…

I was five feet tall and weighed 80 pounds.

My first time grabbing steps on the move with my husband pulling me up, I cried like a baby. I soon got over that and could get on with the best of them.

“We carried cardboard suitcase with one blanket, two potatoes, one onion, and two slices bacon, an army fry pan.”

I was so impressed by the fact that well-educated people were also on the road and looking for work.

A woman traveling alone with three children. She had a few sandwiches and offered to share. We thanked her but refused. We couldn’t take food from the children even though we were starving.

INDIANA

Donald Newhouser

I was born in 1916, on a farm in Nebraska and lived through the drought, dust storms, and the Great Depression. I witnessed the heart-rending results of the 1929 Stock Market Crash.

I saw children coming to school in zero weather with holes in their shoes, thin coats and no gloves. We would have a bucket of snow ready to put their frozen hands in as they came screaming into the school house after walking two miles to get there.

One little girl came in, with eyes swollen from crying, and after further questioning stated that her father had tried to kill her. After we asked her why, she said " Because there was nothing in the house to eat."

She said her father was holding her over the cistern, by her fingers, ready to drop her in, and her mother was praying and begging him not to, and was all that saved her.

I was one of the few farm boys that got through grade school, and high school, as schooling wasn't considered necessary to be a farmer. I received a scholarship, which didn't amount to much in those days. It paid the tuition for two years to a teachers' college, and I didn’t want to be a teacher.

I got the only job could find, on a cattle ranch. It paid $10.00 a month plus my room and board. Realizing, after a few months, that such a job would get me nowhere fast, I resorted to the only means of transportation I could afford and that was riding freight trains.

I followed the harvests through the west, or wherever I could find work. The hay fields in Colorado, potato picking in Idaho, apples in Washington, hops in Oregon. From 1935 through 1938, and learned the tricks of the road. How to grab a box car doing 30 miles per hour, how to walk on top of a train doing 50, what not to ride on, and never, never get friendly with any one.

Some where in Montana mountains, the noisy Mallet engine came to a screeching halt on a side track. I heard it being disconnected from the old worn out cars, and take off, possibly for more coal, water etc. Any way the silence was unbearable after listening to the constant hammering of the mallet engine, climbing the steep curves, and the rattling box cars and squeaking wheels.

A variety of men and kids climbed down off the cars, some headed toward the jungle camp found near every railroad yard. Some walked up a narrow path, through a grove of trees, towards a dim light in the darkness, coming from a old shack back against the mountain.

I watched suspiciously for a time, then decided to find out what the attraction was, at that shack. I learned long ago to be alert, but not act that way, so staggered along like the others did, stiff legged and hump shouldered, watching some go in, and some go out.

The little old shack turned out to be a store, with tobacco, coffee, candy bars, bread, sugar, flour etc. A large black board had a notice written in chalk: I AM DEAF -- please point at what you want.

I was watching the store keeper and figuring him out to be a sneaking character, with heavy eyebrows, large mean looking eyes, and a wedge shaped face, when a dog barked out in the back of the store. Immediately the man raced to the back of the store and after a short time, returned to the store, and with a fast searching glance started waiting on the customers again.

He didn't notice, but I was really alert now. He had heard the dog!

The sign said he was deaf, so evidently he didn't want to talk or be asked questions. It was a good hide-out, all right. I bought a sack of Bull Durham and left. It was no place to let anyone know you had much money.

I wandered back to the jungle camp, where a fire was burning, coffee was being made, and men sitting around on boxes, or on the ground talking. A train whistle way off around the bend, alerted every one and a five-year-old boy said "Dad, here comes our train."

The train slowed down as it passed through the switch yard and every one got aboard.

The next day we traveled until late in the afternoon, and since it was again my second day without eating, I was getting desperate. Every man crawled off that train bummed every one they saw, for food, money or anything they could get. It was really embarrassing to me as I couldn't do such a thing.

I stood on the street corner watching them, when an old lady walked up and said, "You poor boy, here's a dime to get a cup of coffee and a donut" I know I turned red as a beet being so embarrassed, but was able to thank her and hurried down the street. Meals cost around thirty cents in those days so had enough to go in and get a warm meal, but not before I was certain no one had seen me go in the restaurant.

I was just finishing my second cup of coffee when I saw two bums had looked in the window and spotted me. I had stayed too long. When I left they followed, so I stopped and let them catch up. They said they knew that no one had any luck panhandling and wanted money to get themselves something to eat. I told them I was broke but they didn't believe me, and wouldn't let me out of their sight.

It was getting dark and I knew what would happen then, so got up and went down town with them close behind. Finally I had a plan and walked into the depot, went to the washroom, removed my dirty overalls and washed my face and hands.

Rolling up my coveralls inside out, and carrying them under my arm, walked up to the ticket agent and asked when the next train was due. The ticket agent gave me the once over, along with the time and I walked over to a bench and sat down. The two characters outside were too dirty to come in, but kept looking in the window, as I sat there looking at old magazines.

The passenger train came puffing in, steam so thick visibility was zero on the platform, so I walked unnoticed toward the front of the train, and climbed up between two baggage coaches, and found room to stand in a door way.

The train took off, wheels spinning, steam belching from the cylinders, whistle blowing, and I figured I had shook off the two that shadowed me all afternoon. It was no easy matter hanging on in between the cars, as the train picked up speed, and then I realized my biggest mistake, too late.

I had escaped the two that were following me, but red hot coals belching out of the smoke stack, bounced along the top of the cars, fell in between, down my neck, and started fires in my clothes. That train must have been doing seventy-five miles an hour and with me beating out the fires on my clothes, and trying to hang on, it was something I don't care to dwell on very long.

The train stopped twenty miles out to take on water, the two bums were spotted on the coal car and kicked off. They shook their fists at me, as the train took off, and I gave them my best victory smile. The place where the train took on water has just a large water tank, called a "jerk water", with no other buildings around and trains may not stop there again for days, making it the worst place for bums to be kicked off.

An incident I shall relate, caused by lack of sleep, empty stomachs and the continual strain for survival: One night while waiting for the switchmen to get a train set up, listening to cars being switched from one track to another, and watching the lanterns swinging stop and go signals, we all fell asleep on a side track, unused for a long time, with weeds and grass grown high, perhaps twenty bums had sat lay there sprawled out.

I lay there with my head off the rail, when a vibration awakened me with a start, and in the darkness I saw a lone box car that had been switched to this side track, barreling down on us at a terrific speed. I yelled at those around me and dived from the track, as the box car thundered by, and believe it or not, every one made it off the track safely.

Whether it was done unintentionally, or deliberately, it was a dirty trick. We knew that many of the switchmen and engineers hated us, as many had been beaten, kicked and shot at, this was murder for sure.

Hundreds of people rode freight trains during those years, for one reason of another, hut mostly because they still had hopes of finding work somewhere. No man in a freight car dared to use profanity if women were present. I saw two men jump up and face another that had done so.

Women riding freight trains safer then than women who walk on the street today.

I thank my lucky stars that I've never been in jail, although I've been caught twice in round-ups, but broke away. I've been shot at, held up, and dumped off on the "Great Divide" in zero weather, but managed to catch the last car and survive.

I was sitting on a railroad track, somewhere in Montana, waiting for a freight train. I was nineteen years old. It was getting dark, and as I looked down at a village below, I saw a Xmas tree lit up in a window and children playing around it. That was the first I knew it was Xmas. Tears ran down my cheeks as I remembered Xmas day when I was the age of those children.

The one thing I enjoyed was the beautiful scenery, the mountain streams, water falls, and beautiful trees. It helped me take my mind off the troubles and dangers I continually faced.

INDIANA

Glen Law

2,500 mile journey from Wenatchee, WA to Manchester en route to college

Appleyard, the Great Northern freight terminal a mile south of Wenatchee...

Mom and Dad drove us there in their Model A Ford. I now have some idea of the thoughts going through their minds as they sat there and watched us climb over the fence, wave, and trudge across the empty tracks. Poverty, love, and a fervent trust in God to preserve us kept them from objecting.

We climbed into an empty boxcar and settled in the doorway, watching Mother dabbing at her eyes and talking to Dad.

Soon we saw him get out of the car, climb the fence and follow us across the tracks.

“Take off those old ragged tennis shoes, Glen. We can’t have you starting college in those. “ I started to argue, but a look at his rigid jaw stopped me.

Without a word I exchanged shoes, and thanked him. His contribution to my college education would not go unappreciated.

With a final, “Goodbye, Boys,” dad turned and almost ran back to the car. We sat there watching them until the train pulled out.

INDIANA

Harriet Dickinson

At Valparaiso, northwest Indiana, my younger brother and I were walking along the railroad tracks a short distance from our small farm

We each had a bucket looking for chunks of coal that might have fallen from a passing coal car. We could a hear a train approaching in the distance so we went down the embankment and waited for the train to pass. There were freight cars and coal cars.

We saw a young man sitting on top of the boxcars. From his perch he could see us with out buckets and immediately jumped up and ran down the row of boxcars until he came to a coal car. He started throwing chunks of coal down to us as fast as he could before the train reached the next crossing.

How happy we were that we could fill our buckets up. There was someone who understood and cared.

INDIANA

Henry Koczur

Rode in Sept 1932 I was 16 “Why should I burden my family? Left home on a freight.”

Three brothers and two sisters; home was in East Chicago.

Rode the rails from 1932 to 1935

Hungry: whittled through side of boxcar = cans = raw oysters

Police raid on jungle: shot holes in stew cans.

Jail breakfast: a piece of bologna 4” long and 4 slices of bread

Why should a man long for such punishment? I got used to rough living

Witness to Memorial Day Massacre x steel mills x South Chicago 1937

Went to fight fire in Saugus, CA: We hiked to the top of the mountain, which was called Castiac Canyon. It looked like the whole world was burning. Narrowly escaped backburn.

Going home: When I put my legs under my father’s table, they were going to stay there, even if I had to eat potato soup three times a day.

I spent two and a half years overseas in a war zone. I was shot at more times in the U.S. while riding freights.

INDIANA

James Taylor

1931-1832 21 years old

I arrived in New Orleans from my home in Indiana, one Saturday morning. I was accosted by a policeman, who asked what I was doing there. I told him I was looking for work, but first wanted to find a cheap hotel where I could have a bath and get cleaned up. He said the city would provide me with lodging and took me to the city jail.

I was put into a holding tank with other vagrants for the weekend. On Monday morning I was taken before a judge, who told me no work was available locally and that I should get out of town as fast as possible.

When I went to pick up my belongings I found all money missing except for a dollar of loose change. When I brought it to their attention I was told to get out of town as fast as possible or face 30 days in road gang.

I teamed up with another hobo while on the final leg from Yuma to LA. He said he had formerly worked for a large trucking company in LA and was on his way to start work with them again.

He was shabbily dressed, while I had on a nice suit and overcoat. I also wore bib overalls while on the trains. I was a gullible farm boy and allowed myself to be talked into trading places with him so he could make a good impression. He was supposed to meet me afterwards. Needless to say I never saw him again.

There was no justice on road.

INDIANA

Leo Hohalek

South Bend Tribune, Feb 15, 1993

I was 21, bumming around the country looking for work.

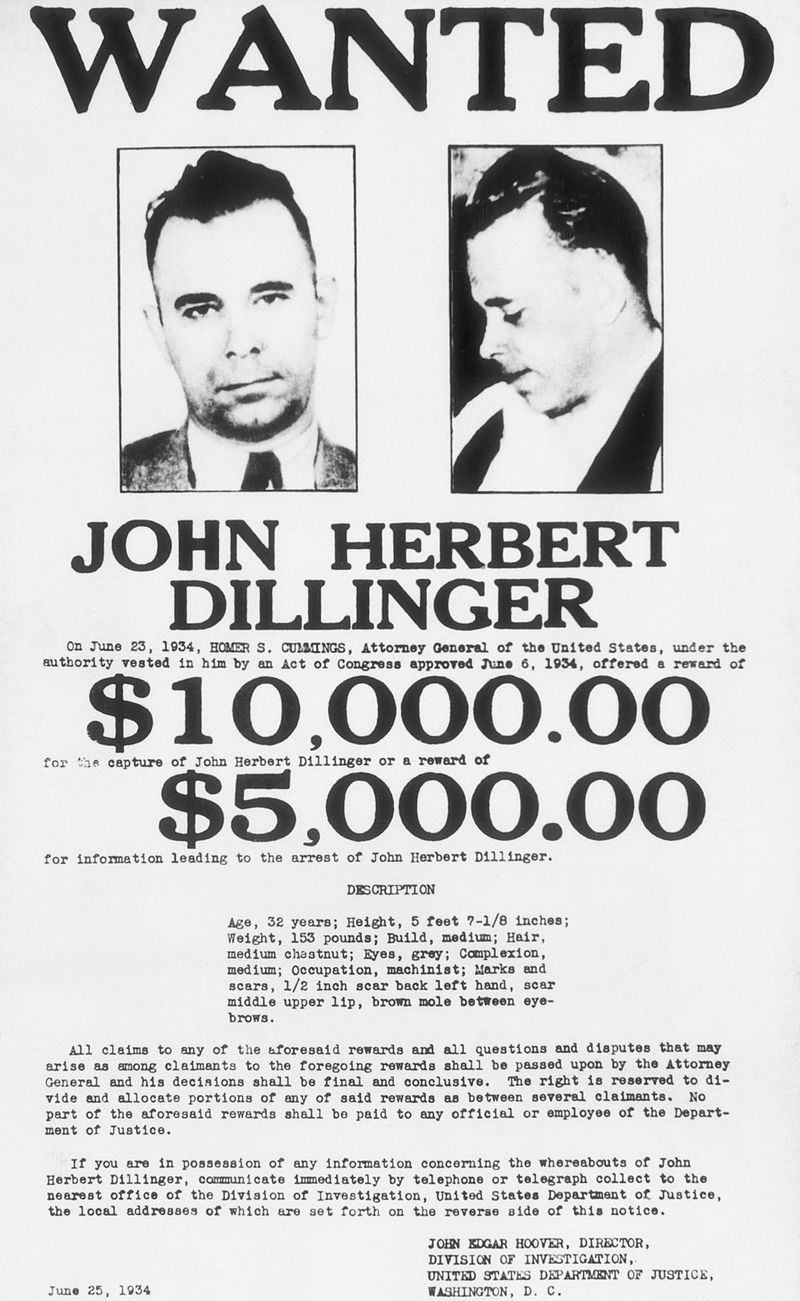

A John Dillinger look-alike.

I was on a boxcar with a dozen other bums in January 1935 when the train stopped for water and coal outside Alfafa Center, Nebraska.

As soon as they saw me one cop yelled through the boxcar to another one, “We got Dillinger. This is John Dillinger."

They were real sure I was Dillinger when they learned I was from Indiana. No one could have made them believe different then.

Hustled off to jail. “They were pretty rough. They kept me in a long nightgown and a cop watched me all night long. He never took his eyes off me.”

He was released the next day after police learned that Dillinger had been killed in Chicago.

INDIANA

Malcolm Stewart

I’d like to comment on the goodness of the people. There were endless handouts for a snack or meal whether you had to cut wood etc. or not. For shelter, if one did not have the price of a flophouse, there were the missions. Then, too, when going through a town the local police might pick you up on a vagrancy charge, let you sleep on the concrete floor in the jailhouse and let you out on the edge of town the next morning.

INDIANA

Ray Bloom

We had been warned to stay away from the railroad in or near Cheyenne, Wyoming.

We got off when the train slowed down enough for us to get off safely. We were safely on the highway when a car drove alongside the train dispatching bulls. They were chasing hoboes. They even chased one running over the top of the railroad cars.

We walked around Cheyenne. We stayed all night on the west side of Cheyenne. We got back on a train that had slowed down going over the first hill out of Cheyenne. We were riding in an empty gondola car. We were joined by several more hoboes before dark. We were all asleep.

Sometime during the night we were rudely awakened by a mean bull. He told us to get off on the north side. When we got on the ground, we were lined up by another bull. He had a gun strapped on his hip. We found out we were in Green River, WYO.

They marched us up to the depot where one searched us. The other one watched with his gun handy. We all had our hands up. When he pulled my tobacco sack from my pocket, he asked What’s this? I said It’s my tobacco and reached in my pocket to show him my cigarette papers.

He said, ”Keep your hands off or I’ll nail you.”

I kept my hands up until he was searching the one next to me. He had left the tobacco sack hanging out side my pocket and so I shoved the sack back into my pocket. He hit me with his fist on the side of my head. I almost went down. He said. "Keep your hands up."

When they let us go we were warned to stay away from the railroad. We spent the rest of the night west of Green River, then got a train west from the top of the hill to Pocatello, Idaho.

Went into the army in May 1943, the 726th Railroad Operating Battalion. I retired as railroad yard conductor in 1975 from the Penn Central Railroad.

INDIANA

Violet Perry

Honeymooners 17 and 21, July 1933

Married in Harrisburg, Illinois

When we got home that night, Red said, "Let's leave tonight!" So down to the yards we went.

We finally got a train out to St. Louis Missouri and there we were stopped.

We had a small suitcase, change of clothes, our marriage license and birth certificates. Since we were married and September l3th I would be 18, they let us go.

Then we happened to get a Red Ball - all cars sealed - and we had to ride an oil tanker. And to make matters worse, it came a terrible storm with thunder and lightening. I didn't have time to be scared for trying to hang on. That's one night I thought would never end.

We finally switched trains and whole families were riding in box cars. We all helped each other.

A man by the name of Blacky Earl from Boston had a large two-gallon kettle in his gear and a banker from New York had a gallon one so we made beef stew in one and salad in the other.

I always went and asked for spices. One time this lady was ironing shirts and she was a little reluctant to give me anything.

So I said, "Lady, let me show you how to iron a shirt."

I just took the iron and, in nothing flat, I ironed the shirt. She said, "How did you learn to iron like that?" I said, "I washed and ironed for 8 people for 2 years - 3 baskets of clothes a week."

She said,”Iron those 3 shirts and I will give you $10.00." She did and also gave me a big bag of spices. Everyone was so proud of me.

We had such a glorious time - moonlit nights on the prairies, deserts and mountains. The wild horses were breathtaking. It’s something you never forget.

When we got into Denver, we had another encounter with the Railroad Bulls. They took us downtown and the Chief of Police was so mad. He said, "Take these kids and feed them and let them go. They look great to me."

We made a beeline for the yards. We thought we had lost our friends. We finally spotted them. Floyd got on first - we were at a crossing where cars were waiting to cross.

Finally I made a flying leap and caught the train as it was rolling - pretty good! My feet flew up to the top of the box car and I heard a woman scream.

I climbed to the top, sat down and, lo and behold, this woman had fainted behind the wheel of her car. I guess she thought I fell under the train. We did have some experiences, but what joy we knew!

I still remember those lovely evenings by the campfire and how good the food tasted. Thank God my mother taught me how to cook, to bake biscuits over an open fire and cornbread in a skillet

We disbanded in Sacramento and Floyd and I hitchhiked to Modesto. We got jobs immediately in the fruit orchards. We worked there till the season was over and then hitchhiked to San Diego and got stuck, mind you, on top of the Ridge Route - it was solid mud! This was February 1934.

Then we came back to San Jose California and worked in the canneries, DelMonte, H.P. Garin, Belfore and Guthrie in Brentwood. We hitchhiked all over the state. We saw California in all its beauty before there were all those superhighways. We saw the glorious fields of hops in Sonora and goats running wild.

KANSAS

Blanche Stovall

“Great Depression was a time of confusion and loneliness, yet bonds of love flowed through the majority of the people.

" Went on to win WWII, working together to strengthen the weaker points.”

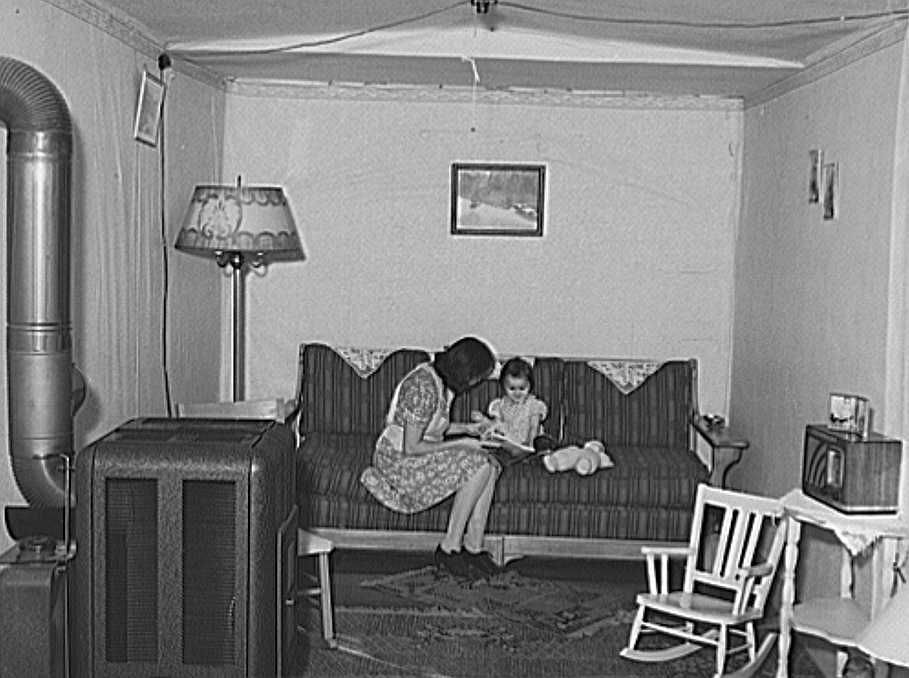

“Tar paper shacks was our only refuge when the dust rolled over from Colorado and Kansas.”

KANSAS

Rex Cozad

1934, 16

Before this trip I had never been farther from home than McCook, Nebraska and Nortin, Kansas.

Shell game: ”The con man left with three or four dollars, an Ingersoll pocket watch and a pair of shoes."

Fruit Growers Association of Colorado ran ad in all mid-west papers for fruit harvest: 5,000 people arrived at Palisade, Colorado to pick peaches.

KANSAS

Leonard Hill

Step-and-a-Half, bull, had one foot shorter than the other and walked on the rails with his short leg.

I smoked tobacco so strong I thought I was going blind, but found we were just going through a tunnel.

KANSAS

Pete Bradford

Railroad bull:“You don’t have a name, so we’ll give you a number.”

However, when they arrived at the small town jail, they found that the officer in charge had gone home. Bradford was released and told to stay away from railroad property, which he didn’t do.

Bradford, from Lyons, Kansas was never homesick. “Not for my parents or Lyons, but what I did miss was the sight of wheat in the Spring, waving in the wind and I am not a farmer either."

KANSAS

Ralph Jones

21, 1937

Left home because of 50 cents to $1 a day wages for 10-15 hour day.

I needed to make the trip home before the weather was too cold and especially before the snow piled up on the Continental Divide. So we both quit the cannery and rode street cars over to San Francisco to the big freight yards.

It was night when we arrived and there were lots of hobos, transients and "whatever" around an enormous fire of battery casings polluting the air. They were telling tall tales; a number of them were African-Americans.

Some told how they wore a big coat and two pair of overalls with the bottom of trousers sewed together and would go in a store and slide articles down the pant legs between the trousers.

It was about midnight when we caught a "chili pepper" or hot shot out of there. They are a long train consisting entirely of perishables, fruits, vegetables, etc. in refrigerator cars. You have to ride the top and they really rattle and roll.

However, I became so accustomed to it that I could slide one arm under the cat walk and grasp the hand with the other to doze and even sleep some.

As I remember, the train went nonstop to Salt Lake City and from there it went on to Pueblo, Colorado, and I don't know the destination after that because we caught another train.

We had no idea what lay ahead after leaving Salt Lake. We traveled through very mountainous country with breathtaking beauty and very precipitous slopes. I found that it was a weird feeling to be sitting in the boxcar doorway and pop around a curve along the edge of one of those places so high up that your legs would be dangling in space.

From time to time we would pop into a tunnel, and in the beginning they were not especially long, but well up the line we went into one that was something else! We heard afterwards that the tunnel was five miles long. We had heard rumors of the Moffat Tunnel which was seven miles long, but that it was ventilated some.

The tunnel we were in surely had a name, but I don't know what it was. I remember when we went in there were five of us in sight of each other, but when we came out there were only three.

It was plenty tough. The farther we went, the more dense the smoke and soot, and it wasn't very long at all when it became so dark and black one could see absolutely nothing. Of course it was every man for himself; keep your head or lose it. I can only speak for myself because there was no communication. You not only couldn't see, but I don’t believe we could have heard anyone unless they were hollering right at your ear. We didn't even want to be near anyone under these conditions because we didn't want anyone in our way to hamper any move we wanted to make.

I had a bandanna handkerchief and soon pulled it out to filter the air through my nose I had wadded it up For more density and filtering effect. After so long a time this seemed to be inadequate, and at the very least it seemed impossible to extract any oxygen from the smoke.

I began to think "this was all she wrote” and held my breath, but then there was some hope. I could see a pinpoint of light, but it seemed the train was going all too slow. But, like waking up after a bad dream, we were out in the fresh air again and I just gulped it in.

As I said earlier, two were missing and I can only guess whether they lost consciousness and rolled off, got scared and rattled and stood up too high and got knocked in the head or perhaps went down a ladder where it was much lower in search of more oxygen and then got weak, or were struck by some obstruction along the side. Anyway the rest of us were filled with thanksgiving.

It shaped my life in a lot of ways. I learned that life lived that way is very real, very basic and the wrong decision at the wrong time can have very devastating effect. One had better be self-sufficient, confident and determined to succeed.

Experiences molded and forged my commitments, my desire to live the Golden Rule, to search for a few really true friends instead of depending on insincere ones but not discouraging ones that are at least not critical or disloyal. Live so as to be proud or at least not ashamed of what and who you are. Believe in yourself, be loyal to your friends but yet be an independent thinker and stand by your principles of what you consider honorable fair and moral.

KENTUCKY

Byron Gatrost

1932, 20

A few miles before we rode into Longview TX all the hobos left the train, about 50 or 60. I ask one why, and they said, “Don’t you know Texas Slim is there?” I was the only one that rode that freight in.

I got off and was weighing myself on the scales when Texas Slim walked up to me. He said, "What you doing here?" I said, "Waiting for a freight." He said, "You’re not catching one here, hit the road" in a very harsh tone.

I walked to the other end of the yards and caught the next one out. Texas Slim was feared by all hoboes.

KENTUCKY

Stan LeMaster

“I find all this interest in hoboes somewhat puzzling. During the Depression, hoboes were mostly people searching for work or going to where they had work. They had little or no money and had to travel any way that they could. They were simply struggling to survive.”

Speech to Owensboro branch of National Railway Historical Society: 3/14/92

“Originally the bulls used the sticks used to set the brakes as weapons to hit with. The railroad companies switched over to long pieces of hose to avoid lawsuits in case someone was killed or suffered broken bones. The hoses would inflict painful bruises. In case an injured person brought a lawsuit against the railroad, the company lawyers would delay the trial. The injuries would heal before they could be shown to a jury. This way, there would be no evidence and the case would be thrown out of court."

There was a common saying, “You can go from two legs to one in twenty seconds."

Riding in an open gondola which was too close to the engine caused my two buddies and me to be drenched in smoke for four continuous hours. The smoke was foul and difficult to breath and as if that wasn’t bad enough, it contained tiny particles from the firebox, some still red.

When the red hot sparks would hit, they would leave a tiny painful burn. When we finally got off, after four hours, our eyes were red and swollen. We never made that mistake again. Experienced hoboes carried handkerchiefs to cover their face and filter the smoke.

Famous hobos: Jack Dempsey, Supreme Court justice William Douglas and authors Louis L’Amour and Jack London were four not ashamed to admit riding the rails.

“I became a hobo – well, because of the life that was in me, the wanderlust in my blood would not let me rest.”