Excerpted from Brazil, a novel by Errol Lincoln Uys

"Descriptions like those of the war with Paraguay, particularly the battle of Tuiuti, do not find in our literature any rival capable of surpassing them and evoke the great passages of War and Peace rather than best-sellers of current extraction. " -- Wilson Martins, Jornal do Brasil

DECEMBER 1868 - MARCH 1870

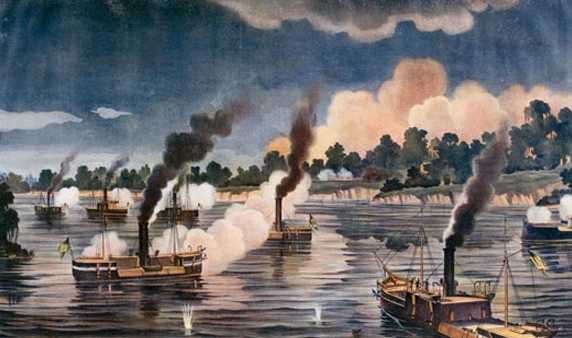

At Itá-Ybate, where Francisco Solano López had his headquarters, first light on Christmas Day 1868 was heralded by a bombardment from forty-six guns and rocket stands deployed in a semicircle opposite the hill. It was the most violent and sustained cannonade of the war, and was answered by six guns remaining in the Paraguayan positions.

Four days ago on December 21 in a blazing 101 degrees, 25,000 Brazilians came down through the Lomas Valentinas from camps near Avaí, reaching positions opposite the trenches below Itá-Ybate at noon. A group had immediately been sent off to destroy the Pykysyry line, which they had done, slaying or capturing nine hundred of the fifteen hundred defenders and forcing the rest to flee toward the Rio Paraguay. At 3:00 P.M. the main attack on Itá-Ybate commenced, with wave after wave of cavalry and infantry charges; the Brazilians took fourteen guns but failed to penetrate López's lines. At six o'clock the assault was called off, with Allied losses at four thousand. But the defenders had been reduced to two thousand men.

The three days from December 22 had seen incessant cannon and rifle fire, but no major moves by either side. On December 24 though, the Allied commanders sent a message inviting President López to surrender, which had been rejected.

The bombardment of Itá-Ybate on December 25 was followed by new attempts to break through the Paraguayan lines. The Brazilians advanced up the hill along two narrow gorges, only to be repulsed again, with heavy casualties.

The next day, seven thousand Argentinians who had come up across the demolished Pykysyry line joined the Brazilians. These fresh troops were to decide the battle of Itá-Ybate.

Again, on the morning of December 27, an artillery barrage thundered against the Paraguayan positions. Then, with the Argentinians in front, the Allied generals sent 25,000 men along the two defiles and up the slopes of the hill. Here and there, a Paraguayan gun, dismounted but propped up on a mound of earth, roared defiantly. Here and there, a lone Paraguayan rose up in the trenches along the hillside, a Guarani war cry upon his lips and his sword raised against an entire battalion running toward him. Here and there, a child of tender years, his body riddled with bullet wounds, lay down to die as silently as he had suffered. By 11:30 A.M., the flags of the Allies flew triumphantly on the shell-splintered flagstaff of Francisco Solano López's headquarters.

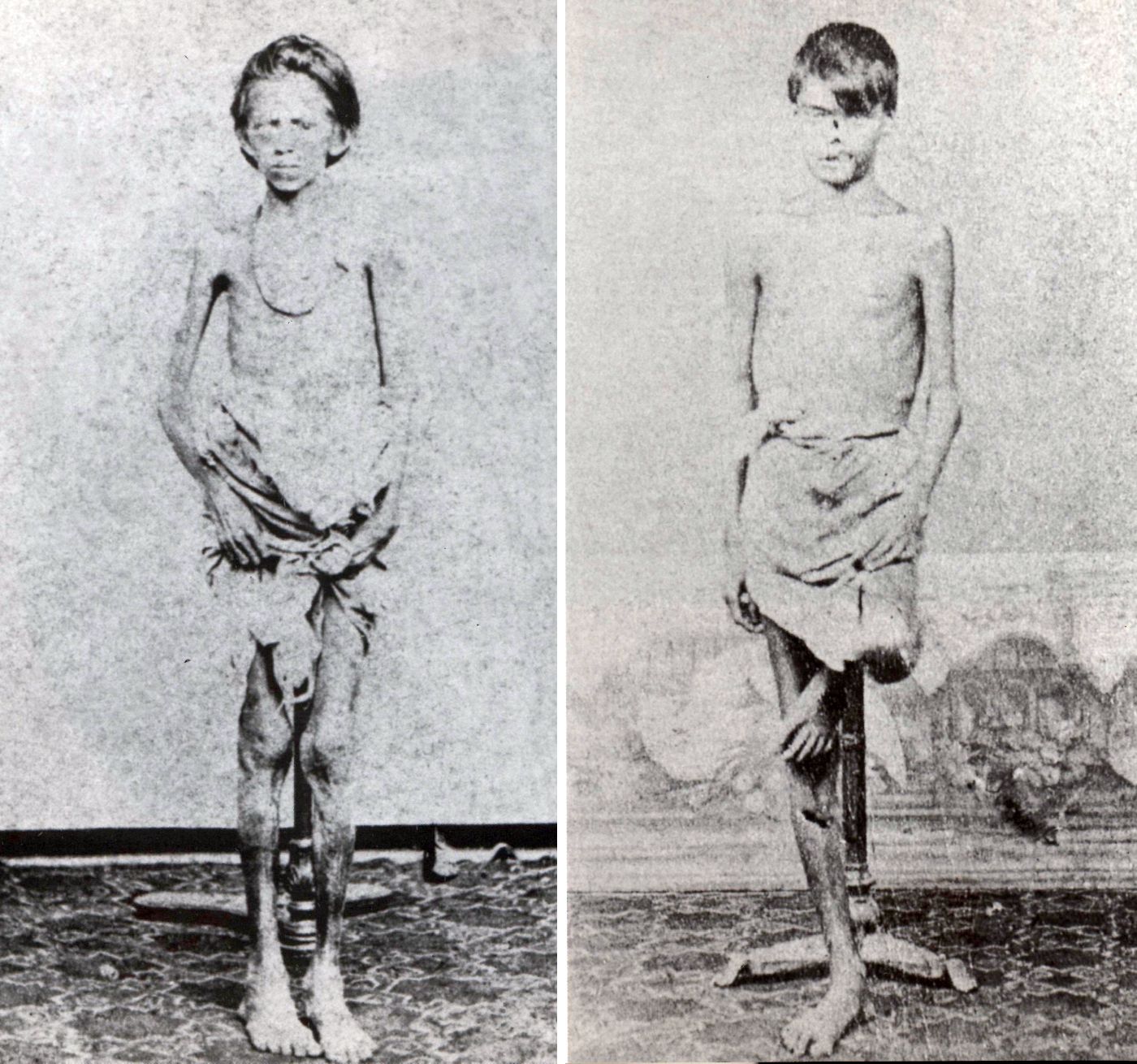

At first, when the Brazilian officer was still a distance away, Antônio Paciência didn't recognize him, and he thought, too, that he was coming toward them with a child in his arms. Antônio, Padre, and a medical orderly were in a wood a mile behind López's headquarters, where the victorious troops had found a stockade holding prisoners of the Paraguayans. As the officer drew nearer, Antônio saw that he was carrying not a child but a man whose small body was horribly emaciated. The officer himself walked unsteadily, his ragged uniform hanging loosely on his frame.

"Gently, now. Be gentle with him," the officer said, when Antônio and Padre helped him lower the man onto a stretcher. "He's been a prisoner of these dogs for four years."

The dark eyes of the man on the stretcher shifted from one rescuer to the next. Suddenly he grew terrified and uttered an awful cry.

"Calma . . . calma, Sabino," the officer said. He reached down, giving the frightened man a reassuring pat on the shoulder.

It was Sabino do Nascimento Pereira de Mendonça, the revenue inspector who had been a passenger on the Marquês de Olinda when the ship was seized by theTacuari. Mendonça's traveling companions, Coronel Frederico Carneiro de Campos, president-designate of Mato Grosso, and the Cuiabá miner and farmer Telles Brandão, were dead, the victims of disease. But Mendonça, for whom life had been a living hell from the instant the Tacuari's gun blasted his ears, had survived the long internment at an estancia north of Humaitá. When López retreated north to ItáYbate, Mendonça and other prisoners had been moved to this stockade.

As Antônio Paciência and Padre picked up Sabino, the officer introduced him self to the medical orderly: He was Major Clóvis Lima da Silva. There had been times during the past thirteen months when Clóvis da Silva himself had not expected to survive his incarceration. At San Fernando, after the retreat from Humaitá, he and other captured Allied officers had been penned up with the political opponents of López: Day after day, they had seen men dragged away for trial and execution.

Antônio had seen Firmino Dantas's cousin at Corrientes and Tuyuti, but did not immediately recognize this gaunt-featured man who had been a captive of the Paraguayans for over a year. The five of them moved off, Clóvis da Silva and the orderly walking beside the stretcher.

"I served with Tenente Firmino Dantas," Antônio told Clóvis da Silva when there was a lull in the conversation between the major and the orderly.

"Firmino Dantas is here?"

"I don't know, Major. After the tenente went to the depot at Itapiru, I didn't see him again."

"Firmino Dantas was back at Tuyuti last November."

"I wasn't there, Major."

"God willing, I'll find my cousin alive."

It was three hours since Itá-Ybate had been taken. For Clóvis da Silva, the relief at being liberated was marred by news that López had escaped with a hundred men.

"How could our generals permit it!" he said to the orderly.

"It's all over, Major. With no army, López is finished. He has no guns. No support. No hope. The war is over!"

"The beast is loose. Until they run him down, López will remain a curse on this land," Clóvis da Silva said, prophetically.

On December 29, forty-eight hours after the fall of Itá-Ybate, the Angostura battery was the only point in the battle sector still held by the Paraguayans. Angostura had been under fire from Brazilian ironclads since December 21, and had received a flood of refugees from the Pykysyry line and other positions; 2,400 men and women, eight hundred capable of fighting, were in the earthworks, with provisions for less than ten days. The battery's guns had ninety rounds of ammunition for each weapon, a supply that would last no more than two hours if they were attacked.

By this night, too, Lieutenant-Colonel George Thompson, commander of the battery, accepted Angostura's situation as hopeless. During the day, he had sent a commission of five officers under a flag of truce to Itá-Ybate: They had been allowed to inspect López's headquarters and interview wounded Paraguayans, and had returned with confirmation of the defeat. After a conference with his staff, Thompson had sent a letter to the Allied generals proposing surrender of the garrison by noon on December 30.

Hadley Tuttle had been with the commission that went to Itá-Ybate, and had voted in favor of capitulation. When Thompson dismissed the officers, Tuttle had stayed behind.

"It's the only thing to do," Tuttle said. "They outnumber us twenty to one, with one hundred guns."

"Not from the Paraguayans' point of view. You've heard them, Hadley. They consider it a sacred duty to oppose the Brazilians to the last man."

"All that matters is to save lives and begin the work of rebuilding this devastated land."

Thompson had been in Paraguay for eleven years. Throughout the war he had served the country with such unswerving loyalty, López had made him a knight of the Order of Merit, the only foreign officer so honored. "Paraguay won't be rebuilt," he said flatly. "Emperor Pedro and his minister, for all their denials, favor annexation. The threat of a war with Buenos Aires - that's all that may stop them."

Tuttle, too, feared the aftermath of war, above all the danger to his wife, Luisa Adelaida, and her family, who left Asunción when López ordered the capital evacuated.

"I must go to my family, George," he said.

"I see no problem. Our surrender is conditional on our liberty to go where we please."

"How long before the formalities are settled, do you think?"

"A few days?"

Hadley laughed. "More like weeks, George."

"Did you forget? The roads to the north are sealed. Perhaps it would be best to wait a bit."

Tuttle shook his head. "No. Tonight, George. I'll go through the Chaco."

Thompson realized he couldn't dissuade Tuttle, and did not order him to stay at Angostura. "You're probably right," he said. "Go to them, Hadley. Get them to safety. God knows, it may not be over yet."

"One drop of blood shed now would be a waste."

"López is making for Cerro León." This was the military base at the railhead fifty miles from Asunción, where several thousand men were in the camp hospital. "The Marshal will get those invalids out onto the parade ground. If the slaughter continues, one man alone will be to blame: Marquês de Caxias. What stops him from ordering the capture of López? Does he want to keep a Brazilian army in occupation and prepare for annexation? Or could it be that the Brazilians want López to escape and reassemble the surviving men of Paraguay?"

Tuttle was genuinely puzzled. "Whatever for?"

Thompson smiled grimly. "Wouldn't it provide, through civilized warfare, the opportunity to exterminate the last Guarani?

From the spires of Asunción's cathedral on the third Sunday of January 1869, the peal of bells rang out over the capital as the marquês de Caxias, his fellow commanders, and a host of Brazilian and Argentinian officers gathered to thank God for victory. Three days earlier, January 14, the marquês issued Order of the Day, Number 272: "The war has come to its end, and the Brazilian army and fleet may take pride in having fought for the most just and holy of all causes."

As the marquês de Caxias and his officers raised their voices to heaven, outside the cathedral the scene was closer to hell. The first Allied troops had entered Asunción on January 1, encountering minimal resistance; a few days later, the bulk of the army started to march in from Lomas Valentinas, until by this Sunday there were thirty thousand men in and around the capital. López had ordered Asunción evacuated months ago. His administration, the remaining foreigners, and the upper-class citizens had gone to towns east of the city; but when the Allied army marched in, there remained several thousand poorer Guarani and mestizos who had not fled or had drifted back to the city from the outskirts seeking food.

And there were the defeated, who watched the macacos stream into a city deserted and neglected, her broad boulevards overflowing with trash and the bloated carcasses of beasts, and stinking like open sewers. Propped up against the wall of the unfinished opera house, leather pads bound to the stumps of his legs, was a gunner who had been at Itapiru resisting the enemy's first approach to Paraguay; in the shade of a tree stood a Guarani lancer who'd ridden for the guns of the Argentinians at first Tuyuti; he'd been blinded by grape, and half his nose was shot away. A mestizo infantryman, the victim of a skirmish in the Chaco, lay on his back, wearing a ragged poncho that failed to conceal his upper legs and genitals, which were reeking and moist with gangrene. "Macacos . . . macacos . . . macacos," the soldier gibbered.

And for every man, there were four or five women and twice that number of small children. The women, emaciated and almost nude, stood silently staring at their conquerors. The children peered out from behind their legs at the giants passing noisily in parade.

The rape of the Mother of Cities by the victors began slowly. A group of camaradas smashed their way into a pulperia and made off with the tavern's most expensive supplies. Looters stormed a silversmith's shop. Frustrated booty hunters torched an empty house. Discipline so broke down that even officers were about, pilfering items for shipment back to Brazil.

The ravaging of the city gained momentum with the rumors being spread about the nature and whereabouts of the fortunes of El Presidente and his mistress, La Lynch. Mobs of soldiers prowled the residential barrios on the outskirts of the city searching for booty. Ax-wielding men chopped through the doors of warehouses and attacked the homes of Asunción's elite, ripping them apart. No place was inviolable: The U.S., French, and Italian consulates were devastated. When none of these efforts uncovered the fortunes of López and Madame Lynch, the soldiers looked elsewhere - to the cemeteries, where the best-appointed tombs were burst open for inspection.

Night after night, the sky above Asunción glowed with fires set by the rampaging soldiers. In the light from those flames, men who were either bored with the treasure hunt or satisfied with what they had already stolen from deserted homes turned to other pleasures: Some of the living skeletons who had lined the streets when the Brazilians marched in gave their bodies freely to the soldiers in exchange for food; other Guarani women and girls had to be held down forcibly, but their cries went either unheeded or unheard.

The sixty-five-year-old marquês de Caxias was well aware that his troops were on a rampage, but two years in Paraguay had left him utterly exhausted and unable to control them. In the cathedral this January 17, during the elaborate thanksgiving, the marquês collapsed in a faint: The following day, Caxias relinquished his command and immediately set sail for Brazil.

Fábio Cavalcanti was present at the thanksgiving service in the cathedral. Cavalcanti and other members of the army medical corps had come up from Humaitá, where they had been based since the garrison's surrender in August 1868; they had taken over the barrack hospital outside Asunción to receive hundreds of wounded men from the Lomas Valentinas campaign.

Like every man celebrating the victory Te Deum, Fábio Cavalcanti, who had been in Paraguay for almost four years, had offered heartfelt thanks for an end to the war. And like others in the weeks following the service, he came to be bitterly disappointed as reconnaissance patrols found that López was up to something. At first, there was talk that El Presidente, his concubine, and their sons were dashing for the Bolivian border. But, as the weeks passed, scouts discovered bands of armed Paraguayans moving up along the cordillera and along lower sections of the fifty-mile railroad between Asunción and Cerro León.

When the marquês de Caxias left Asunción, the command of the army passed to a field-marshal, Xavier de Souza. When it dawned on the army that they might yet have to march again to mop up Guarani resistance, morale collapsed. The soldiers intensified their depredations against Asunción; many officers sought and were granted leave to return home for reasons of poor health, though most were simply sick and tired of the war, and some began to talk of the need to offer López terms for an honorable surrender.

A thousand miles away, His Imperial Majesty Dom Pedro thought differently. Supported by his more bellicose ministers, Pedro reaffirmed his belief that Brazilian honor demanded the elimination of Francisco Solano López. What was needed to achieve this, His Majesty decided, was a young commander capable of reinvigorating the imperial army and leading the hunt for López - a bandit upon whose head His Majesty now placed a reward.

The young man whom Emperor Pedro chose for the final conflict was his son-in-law, the twenty-six-year-old Prince Louis Gaston d'Orléans, comte d'Eu, husband of the imperial princess, Isabel. The comte, who had reached Rio de Janeiro on the eve of the war, had been considered too young and inexperienced to go to battle alongside such veterans as Caxias and Osório. There was also some question about the comte's ability to inspire Brazilian troops. In March 1869, however, Dom Pedro and his ministers appointed the young Frenchman marshal in full command of the Brazilian army in Paraguay.

Fábio Cavalcanti was among the hundreds of officers who went down to Asunción Bay on April 14 to greet the comte d'Eu. Prince Louis Gaston set up head quarters at Luque, eleven miles to the east of Asunción, and wasted no time beginning an overhaul of the army. But, on April 28, he reluctantly agreed to a suspension of drills and inspections while the army mounted a review in mass and held a festa to celebrate the twenty-seventh birthday of its new commander-in-chief.

On the night of the comte's birthday, the officers of the medical corps held a dance in their quarters, the villa of an army doctor who had been executed for treason at San Fernando. The rambling single-story house was neglected, its whitewashed walls stained with red dust; its huge garden, though overgrown, carried the scents of magnolia, jasmine, gardenia.

When the bandsmen playing for the officers and their guests were almost ready to end their performance, Fábio was out in the garden, experiencing an odd mixture of joy and guilt: In this dolorous land, where he had witnessed so much pain and suffering, he, Fábio Cavalcanti, now found himself sublimely happy, strolling arm in arm with Renata Laubner.

Fábio had gone back to the main hospital at Corrientes after tending the wounded from second Tuyuti at Paso la Patria. Again, he had watched wonderingly as nurse Laubner cheered up her patients, the majority of them freed slaves and rude sons of the backlands. And this time he had taken every opportunity to show his affection for her, knowing full well he was but one among many who cherished the hope of courting Senhorita Renata. And then came the night when they sat together on a bench on the hospital grounds at Corrientes and Renata laid her golden head against his shoulder and said, "I love you, Fábio."

When Humaitá had been surrendered, Fábio was sent there with other doctors to take over the garrison hospital. Renata had asked her superior, Dona Ana Néri, for a transfer to the fortress, which a sympathetic Dona Ana had granted, there being no secret about the love between Dr. Cavalcanti and nurse Laubner. Early in January they had been so hopeful that the war was finally over and they could go home - first to Tiberica, where Fábio would ask apothecary August Laubner for his daughter's hand, then to Recife, Pernambuco.

Renata knew that Fábio was compassionate and understanding, and loved her dearly, but even as a child she had noted the contempt of the fazendeiros toward the common people, like the Swiss, they hired to pick their coffee. She remembered what her father had said to her the night they went to the ball at Itatinga: "We are here, daughter, because Baronesa Teodora Rita invited you to the fazenda. The barão himself welcomes me, apothecary Laubner, from whom he takes his pills and tonics, but I see he is not happy. It bothers him to have a poor, untitled, unlettered man like August Laubner among his guests." There had been no rancor in his voice.

Oh, how she had danced that night! How she had flashed her eyes and laughed and sighed in the arms of the handsome grandson of the barão de Itatinga!

And he had come to her afterward, treading softly into her father's shop, saying she was the loveliest girl in the world. When her father remarked on his visits, she had said, "Don't worry, Papa. They already plan to marry him off to the baronesa's sister. Besides" - and she'd kissed him on the cheek - "I'd never be comfortable in a house where my father wasn't welcome!"

And now she was apprehensive about the reception she would get from other members of the Cavalcanti family. To waltz around playfully in the arms of Firmino Dantas was one thing, but to walk into the Casa Grande at Santo Tomás the chosen bride of Doutor Fábio - she prayed that she would have the patience and strength of her papa, who had refused to be the slave of the fazendeiros.

Fábio had no such doubts about his family's acceptance of Renata. "Soon, my love, soon we will be walking like this but in the beautiful gardens of Santo Tomás. There the air is sweeter and -"

"Oh, Fábio, how I wish it!" Renata burst out. "I wish the war was over!"

"It won't be long, my dear. Three months, they say. López has at most three thousand men, most of them in bandages." Fábio himself added soberly. Suddenly he quickened his step. "My darling, let's go inside. It's the last waltz!"

Thirty miles beyond the comte d'Eu's headquarters at Luque lay the long valley of Pirayu, with wooded hills rising on either side. On April 30, 1869, forty-eight hours after the celebration of the comte's birthday, in the dead of night, forty enemy raiders entered Pirayu on their way to offer Prince Louis Gaston a different reception in the land he had come to conquer.

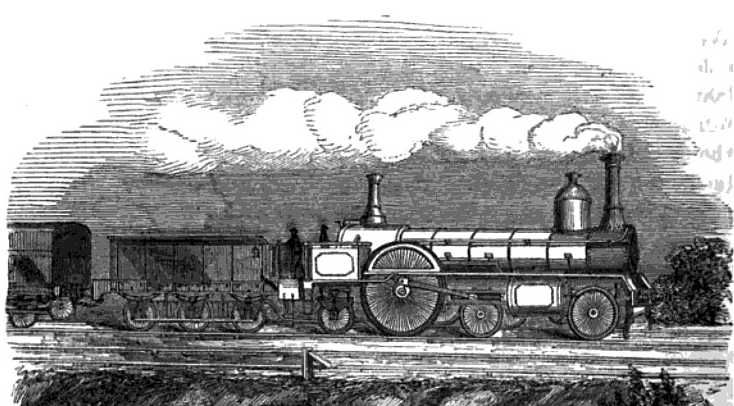

The raiders did not travel quietly. They burst into Pirayu from their base camp at Cerro León to the south in a locomotive hurtling past the dark slopes of Mbatovi Mountain at the bottom of the valley, with two tattered red, white, and blue banners of the Republic of Paraguay streaming to each side of the engine's smokebox, its chimney spewing a fiery rain of hot ash and cinders. The raiders rode on two sandbagged flatcars, one coupled in front of the engine, the other behind the tender, each car carrying a three-inch field gun.

The engine was a rickety piece of equipment, nineteen tons of iron and brass, but her two six-foot-high driving wheels powered her forward at a cracking forty miles an hour: She had been built twenty-five years ago at the great works in Crewe, England, and had served the London and South Western until late 1854, when she had been shipped out to the Crimea. As she chuffed along, the glow above her chimney illuminated the name plate on her boiler: Piccadilly Pride. Standing on her footplate was Major Hadley Baines Tuttle, who knew her well, old Number 11 of the Balaklava line, which he had helped to lay on the hills overlooking Sevastopol in that murderous winter of 1855.

"Say, Hadley, man! We've seen a wee miracle here!" Scotty MacPherson had declared earlier at Cerro León station, when the armored train was ready to depart. Scotty was referring not only to the raiding party with Piccadilly Pride but also to the astonishing fact that four months after Francisco Solano López had fled Itá-Ybate with a handful of officers, he was ready to march again with an army of thirteen thousand soldiers.

The nucleus of the force comprised fifteen hundred troops who had withdrawn from Asunción on the eve of its occupation by the Allies; among thousands of wounded at Cerro León, as soon as a man had strength to pick up a rifle, he, too, joined the ranks. But the majority responding to López's call came in small groups from every corner of Paraguay: escaped prisoners of the Allies, soldiers who had been scattered across the countryside during the Lomas Valentinas battles; veterans who had laid down their arms welcoming peace but chose war again when they saw what the invaders were doing to their country; tribesmen from the interior of the Chaco, where they had heard talk of the macaco horde, a pest greater than the Spaniards and other interlopers they had resisted for generations.

Guarani had come with their own ancient muskets; with homemade lances and swords hammered out at village smithies; with weapons and ammunition stolen, item by item, from Allied camps. Parties of men scoured the deserted Pykysyry trenches and other battlefields returning with discarded arms and cartloads of cannon balls and shell fragments. The latter, along with every church bell and other useful piece of metal, were delivered to a makeshift arsenal where Scotty MacPherson and other foreigners were employed.

At the arsenal, near López's provisional capital of Piribebuy just north of Cerro León, Scotty and his engineers had by April cast eighteen new field guns and mortars; several hundred thousand shells had been stockpiled. They had also made the light guns for the flatcars coupled to Picadilly Pride and had bolted high iron plates to the sides of her open engineer's platform to give the men there protection from enemy fire.

Hadley Tuttle had been reunited with Luisa Adelaida and her parents in late January at an estancia outside Piribebuy. They had stayed there since then, Scotty working at the arsenal five miles away, Hadley taking patrols into the cordillera, where he had surveyed the escarpment for trenches and battery positions, putting to good use his experience with Lieutenant-Colonel Thompson, who had left Paraguay after the fall of Angostura.

With Thompson gone, Hadley Tuttle was among López's senior officers. El Presidente had come close to total defeat at Itá-Ybate: He had made his last will and testament on that hill, leaving all his worldly goods to Madame Eliza Lynch. In the four months since Itá-Ybate, as thousands of men and boys rallied to him, and his anger and sorrow rose at reports of the devastation of Asunción, López had found new spirit to combat the enemies of the fatherland.

Among those foes were Paraguayans suspected of plotting to overthrow the dictator. There were still a number of prime suspects under guard at Piribebuy, among them Venancio López, his other brother; two sisters; and, most injurious of all to El Presidente, his mother, the aging Dona Juana.

As Piccadilly Pride shot along the valley, Hadley Tuttle was confident of success. The Piccadilly Pride had a run of twenty-two miles to her objective, an advance Brazilian post near the comte d'Eu's headquarters at Luque. The train had to pass through two stations above the valley of Pirayu, both of which scout patrols had reported deserted. Beyond the first of those stations, the railroad skirted the lake of Ipacaraí, at the tip of which was the village of Aregua, where the Brazilian forward units were camped.

Piccadilly Pride chugged comfortably up through a forested incline at the head of Pirayu valley. Beyond the forest, the engine picked up speed passing Tacuaral twenty minutes later, the station silent and deserted as the scouts had reported. Great Ipacaraí was off to the right now, the railroad skirting the lake. A six-mile run beside Ipacaraí and Piccadilly Pride passed the second unoccupied station, Patiño Cué. Aregua, the Brazilian advance post, lay six miles farther along the track. There was a cutting a mile from Aregua; beyond the cutting was a bend in the tracks, then a straight, level run to Aregua bridge, 138 feet long, supported by a trestled framework of ironhard timber.

Half a mile from the cutting, Hadley eased off the throttle, until Piccadilly Pride was panting along slowly. Entering the cutting, Hadley put the engine in reverse. The big driving wheels bit the iron rails, and Number 11 came to a stop with a shudder and hiss of steam.

When Hadley climbed down from the engine, the soldiers were assembling in front of the train. Five minutes later this group began to move off up along the railbed.

Hadley walked with the Paraguayan sergeant in charge of the company, Julio Nuñez, who had served with Hadley at Angostura. Nuñez was taking eighteen men to deal with a guard post on the north side of the bridge.

"They'll be asleep, Major," Nuñez said, the stub of a fat black cigar jammed in the corner of his mouth.

"I wouldn't count on it."

"At this hour? Macacos sleep, Major!"

Hadley accompanied them as far as the bend beyond the cutting. "If there's trouble, you know what to do," he said to Nuñez.

Hadley glanced at a soldier carrying two signal rockets; in the event of trouble, they would be fired. Tuttle would still make the run with Piccadilly Pride, hoping to force their way across, but it would be far better if the bridge, and their escape route, was secured.

"I promise you, Major Hadley, not one will sound the alarm."

Seven Brazilians had been posted to guard the bridge, but not one was alert. It was almost 2:00 A.M., and Nuñez's confidence was not misplaced, for the macacos were asleep, including one voluntário who had fallen into a deep slumber up on the bridge as he lay on his back between the rails. He did not wake until the instant a Paraguayan crept up to him: The man slit his throat. It was the same with the Brazilians in the tents.

Ten minutes later, Piccadilly Pride puffed out of the bend beyond the cutting and gained speed along the straight, level track to the bridge of Aregua. It rumbled onto the 138-foot span, running smoothly, the noise of her driving and coupled wheels, iron against iron rails, amplified, the flatcars clanking along with a jangle of links and pins. Past the bridge, fifteen hundred yards to go, Piccadilly Pride rolled on almost sedately at low speed to bring her to an easy halt within range of the enemy camp.

The gunners had loaded their pieces with projectiles that would ignite on impact, setting fire to everything within reach. This bombardment would be followed with canister delivering a hail of iron balls.

The small lead gun fired, with a bang and a flash, the first shell exploding to reveal a row of tents ahead and off to the right. A shell from the rear gunners shooting from a difficult angle fell short, but the flames showed men falling out of the tents. The gunners pumped rounds of carcass shot into the camp, the intense flame of these shells making a bonfire of tents and supplies. Hadley himself blazed away at the enemy with a .44 revolver.

But twenty minutes into the attack, the Brazilians began to retaliate effectively. Three of the men on the lead gun car were shot in quick succession.

With a long toot-toot-toot on Piccadilly Pride's whistle, Hadley signaled they were pulling out. "Come on, old warrior!" The old engine responded beautifully. Under a small cloud of black smoke, Piccadilly Pride backed up, showering soot on the men up front, where the three-inch gun kept firing to keep the enemy at bay.

Sergeant Julio Nuñez ran along the bridge beside the engine as Hadley backed her up. Nuñez shouted that charges were placed in the trestles; his men were ready to fire the gunpowder.

Brazilian soldiers who had run down the tracks began to shoot at them from positions north of the bridge.

Julio Nuñez himself was a victim of this exchange. Struck by a bullet that ricocheted off the engine's tender, he plunged headlong to the timbers beside the track.

Hadley backed up Piccadilly Pride as fast as he could go, to one hundred yards beyond the bridge. Then the charges blew with a thunderous roar, and flames leapt into the sky. Momentarily nothing was heard but the hiss and pant of Piccadilly Pride; then there was a mighty rending and crash of shattered timbers.

"Good work, men. Good work!" Hadley shouted amid the cheers of others as Aregua bridge came tumbling down.

They stopped to take on water at Patiño Cué. The small town was deserted, with its population moved behind López's lines. While the engine's tank was filled, some soldiers wandered off, smashing their way into a pulpeira, where they found a barrel of rum left behind by the owner. There were yells of laughter from another group who found a fat pig trotting down a street near the station: They cornered the terrified beast, slashed its throat, and lugged it back to their flatcar, where despite the protests of the wounded, the porker was hefted aboard.

It was a half-hour before Piccadilly Pride's whistle blew and they were on their way again, with the liquor flowing and the laughter and singing growing louder mile by mile.

Hadley rejoiced with his men. He sent the engine backward smartly, the pile of wood in the tender low enough for him to see the rails behind.

The Brazilians had been bloodied, with one hundred casualties, a third fatal, and their camp a shambles. But out of this debacle rode three hundred horsemen belonging to a superb Rio Grande do Sul cavalry regiment. A mile south of Aregua, they forded the river. They did not sweep directly back to the tracks but thundered along a road that led to the valley of Pirayu.

Piccadilly Pride chugged along beside Ipacaraí Lake and then past deserted Tacuaral, the last station before Pirayu valley. Hadley had her throttle open halfway, for there was no need to race on this last leg home.

"Fool! He'll get himself killed!" Hadley shouted as one of his men leapt from the lead car onto the front of Number 11. The soldier was cheered as he loosened one of the flags next to Piccadilly Pride's smokebox; balancing precariously on the frame, he waved the banner and cheered for Paraguay.

They were two miles from the forest at the head of the Pirayu valley when the Brazilian horse soldiers came thundering toward the tracks. Twenty-five of the cavalrymen had soon detached from the main group to await the train in the valley itself.

"Oh, damn!" Hadley cursed aloud, and flung open the throttle.

There was a scream as the man who had remained perched on Piccadilly Pride's frame lost his footing and fell between the engine and flatcar. There were anguished shouts from the soldiers on both flatcars as they tried frantically to prepare for the onslaught. The prize pig was dumped as the men on that car sought to swing the fieldpiece around.

The cavalrymen did not quite know how to assault the monster, the first armored train to ride the rails in South America. As they stormed the train, Brazilians were killed by their comrades shooting wildly in the melee; others fell to their death after hurling lances that clattered harmlessly against Piccadilly Pride's iron sides. But they were 275, and the men on the train who were not wounded, thirty, and wave after wave swept in, emptying their carbines and revolvers, charging beside the flatcars with lance and saber, raking them with lead and laying open heads and shoulders with their steel-bladed weapons.

Piccadilly Pride had picked up speed as she reached the forest and the decline, now, at the head of the valley. The cavalry were rapidly thinning out as exhausted chargers dropped behind.

Hadley scarcely had time to register his shock at the sight that suddenly loomed ahead of him. The cavalrymen detached from the main body had reached the bottom of the incline ten minutes before the attack and had heaped up logs on the track, throwing the last one on the pile as the train started down the slope.

"God blast them! The bastards!" He could not stop Piccadilly Pride, not a chance.

The rear flatcar rocketed into the logs. The nineteen-ton locomotive jumped the rails, her great driving wheels gouging the earth, plowing up dirt, splintering felled trees like twigs. With a screech of tortured metal and breaking parts, the engine tipped over, hissing and spluttering as water gushed out of her tanks and piles until nothing remained to cool the fire in her iron belly. In a matter of seconds, her over heated boiler blew with a terrific explosion, throwing iron like shrapnel, killing two cavalrymen who stood in the trees watching her die.

And then all was silent around Piccadilly Pride, engine Number 11 of the Balaklava line. Major Hadley Baines Tuttle, who had met her in the Crimean winter of 1855, lay close by, his long fight to help the warriors of Paraguay ended.

Paraguayan hit-and-run raids continued and the Brazilians retaliated in force, but in the Allied camps, most of May and June was given over to preparing for the final campaign. By the end of June, the Brazilian imperial army had twenty-six thousand battle-tested veterans ready to march. Several thousand Argentinians and a token squad of Uruguayans were on hand, but the last push against López was to be essentially a Brazilian effort, with the army divided into two corps, one of which was commanded by Osório, The Legendary.

At the beginning of July, the long columns of infantry, cavalry, and artillery rolled forward slowly until they reached the valley of Pirayu. North of the valley, the forested heights of the cordillera held the advance positions of the new Paraguayan line; eight miles northeast of the cordillera lay Piribebuy, provisional capital of Marshal-President López.

On August 1, the comte d'Eu gave the order to advance. The plan was a pincer movement to envelop Piribebuy: Argentinians, with heavy artillery support, were to move northeast up the escarpment against the Paraguayan right; the bulk of the twenty-six thousand Brazilians were to march southeast to cross the cordillera and deal with the Paraguayan left.

On August 11, Piribebuy was enveloped, and the next morning, after a devastating artillery barrage, the town was taken.

The army marched on, for Francisco Solano López, the beast who was the prey of this great hunt, remained at large. On August 15, the Brazilians took Caacupé, where the Paraguayans had their arsenal, with little resistance. Among the Europeans taken prisoner was Scotty MacPherson. Luisa Adelaida Tuttle, pale and dressed in widow's black, stood silently between her mother and father as a Brazilian officer offered congratulations for their liberation from the tyrant López.

At dawn on August 16, the sledgehammer was raised again on a plain called Acosta Ñu, sixteen miles north of Piribebuy. The comte d'Eu brought twenty thousand men with him and divided them into four divisions, one on each side of the plain. Facing them in the red earth trenches were 4,300 Paraguayan soldiers, the rearguard and largest surviving contingent of the army López had built the past summer.

Among thousands of Brazilians at Acosta Ñu were three veterans who had been in the war from the start: Colonel Clóvis Lima da Silva; Lieutenant Surgeon Fábio Alves Cavalcanti; voluntário Antônio Paciência. They were all witness to what happened on the plain of Acosta Ñu this southern winter's day in August 1869.

Clóvis da Silva, fully recovered from his incarceration by López and recently promoted to colonel, commanded an eighteen-gun battery on a knoll 2,100 yards west of the Paraguayan trenches. On eminences to the south and east were more howitzers and guns to sweep the enemy positions with a belt of fire. At 7:00 A.M., Colonel da Silva gave the order for two guns on the right of his battery to fire the first rounds.

As the artillery crews came smartly to orders, Clóvis da Silva stood with a telescope glued to his eye. The morning was overcast, a raw chill in the air, with patches of mist hanging over the plain, which was covered with clumps of macega , a short, hardy grass. Clóvis saw sections of the Paraguayan earthworks and part of their camp - a long, dark smear in the macega.

"Ready! Fire! Fire!"

Clóvis's body stiffened noticeably as the guns roared out. Mentally, he counted off the seconds, waiting for the distant boom. He held the glass steady, watching the shells burst. Immediately, there were other loud reports from the other batteries.

"Another round, Number one and two," Clóvis ordered. "More to the left."

Clóvis cast a practiced eye over the gunners as they loaded charges and ammunition, trained the pieces laterally, adjusted elevation, and stepped to their places to the right and left at the command "Ready!"

"Fire! Fire!"

Again, Clóvis counted off the seconds before the shells burst, throwing up earth and dust at the Paraguayan trenches. Again, there were explosions from the Brazilian cannon on their right.

And from the enemy, answering fire, the first shells from six Paraguayan guns facing their position, whistling high over their heads to explode behind them.

"Keep this range," Clóvis ordered. "Battery fire!"

Clóvis da Silva's battery and the artillery to their right hammered the enemy's positions. The Paraguayans returned fire with twenty-three fieldpieces, and where there had been mist, there were patches of drifting white smoke.

By mid-morning, the infantry and cavalry attacks began. The overcast sky livened with battle's fury; the white kepis of thousands of soldiers spread like blossoms in the macega, the steel of their bayonets dull gray as they pressed toward the enemy's trenches. And coming down from the north-still too distant to be more than a dark, indistinguishable mass; still too distant to hear the rumble of the earth - were the first blocks of cavalrymen unleashed from the body of eight thousand waiting to assault the enemy.

The Brazilians attacked from every direction, bullets humming and hissing through the macega. The cavalry sweeping down from the north tore into a band of Paraguayan horses riding out to meet them, sabering to the left and right, making swift work of the slaughter. But the Paraguayans' inner defenses withstood the first onslaught and kept the Brazilians pinned down in the macega and at the overrun advance trenches. There was a lull in the battle. Then the Brazilians launched fresh assaults, hour after hour, slowly but relentlessly cleaning out the Paraguayan trenches.

Lieutenant Surgeon Fábio Alves Cavalcanti was at a field hospital two miles south of Acosta Ñu. There had been a steady trickle of ambulance wagons since early morning, bringing the human wreckage of battle to be pieced together, stitch by stitch.

Mid-afternoon, Fábio was still at the operating table. The orderlies had brought him a screaming Paraguayan, with one foot sliced off and one leg pulped below the knee, a Guarani boy, no more than twelve years old.

In the sixteen days since the start of the campaign across the cordillera, Fábio Cavalcanti had experienced a growing sense of tragedy. The sight of victims like this boy were ever more frequent as the Brazilian columns obliterated the enemy's position and drove in the Paraguayan left. Two days ago, at Piribebuy, Fábio and his fellow surgeons had treated fifty-three of their own wounded. It was more than the carnage at Piribebuy that troubled Fábio: There were reports that the Brazilian troops had massacred women and children fleeing the ruined town. There was a rumor, too, that the infirmary of Piribebuy had been purposefully set alight and those within prevented from fleeing that hideous bonfire.

Fábio had left Asunción in June, with the medical corps, for the cordillera campaign. Renata had remained at the barrack hospital, and Fábio was thankful she was spared the horrors of this final thrust against the enemy - for that it would bring an end to the war, he had no doubt.

In the operating tent, the Guarani boy, sedated with ether, lay naked on the table. Fábio and his helpers staunched the flow of blood where the boy's foot had been severed; the other leg was amputated below the knee.

The boy died while they were stitching the flaps on the stump.

Late afternoon at the plain of Acosta Ñu, the Paraguayan lines were collapsing. For nine hours they had withstood the onslaughts, but on every quarter now, gun positions were overrun; trenches were stormed and taken. Hundreds of prisoners were being driven back behind the Brazilian lines.

"C'est magnifique!" said the comte d'Eu at his headquarters near Clóvis da Silva's battery. "Ce moment de la victoire!"

The homely Prince Louis Gaston had proved himself a veritable tiger in battle, galloping fearlessly from one position to another exhorting his troops to fight. And now, as the overcast sky darkened, the moment of victory was almost at hand.

There was a wood just south of the plain. In the fading light, and viewed from a distance such as lay between the comte's headquarters and the forest, tiny black dots could be seen emerging from out of the trees, scuttling through the macega toward the Paraguayan lines; they looked like so many squads of small, dark peccaries bolting through the grass. And like wild pigs, they provided excellent sport for cavalrymen who rode them down, sticking them with their lances.Stubborn Guarani still held patches of macega. So the grass was set on fire. It burned furiously, the flames consuming the wounded who lay there and driving their comrades out into the waiting lines of Brazilian steel.

The battle of Acosta Ñu was over. But once again Francisco Solano López had escaped his pursuers. As night fell, Brazilian scouts rode in to report López and the remnant of his army - a vanguard of two thousand, at most - miles away, moving to the north.

The 4,300 Paraguayans holding the plain at Acosta Ñu all day long had bought precious time for López - at the cost of two thousand lives. Of these, eighteen hundred were boys, and there were children of six and seven here, lying beside flintlock muzzle-loaders.

That night, Antônio Paciência and Henrique Inglez were sitting on the parapet of an earthworks; Tipoana was down in the trench, inspecting the crowded dead with a lantern. Behind them at numerous fires, their comrades were rejoicing.

"Ai, caramba! Meninos . . . meninos . . . meninos!" Tipoana complained. Boys! Just boys! No commanders-in-chief with gold crosses and silver spurs; no select pickings for Urubu, king of corpse robbers! He prowled down there all the same, rolling over small, mutilated bodies, poking into pockets, exclaiming hopefully when he came to an old man who had come to battle in a shabby frock coat. But the veteran's pockets offered nothing of value to Tipoana.

"You're wasting your time," Henrique Inglez said. "The bones of Paraguay are picked clean!" He turned to Antônio: "What more does he want?"

They all had their share, Antônio knew. He himself owned a pouch of gold and silver coins.

Urubu came back along the trench. "Meninos!" he whined. "Not one peso among the lot of them!" There was a boy at his feet. Urubu bent down to pluck some thing from the corpse. Chuckling malevolently, he straightened up, holding the object in the light of his lantern.

Henrique Inglez's long, narrow face contorted with rage, his buckteeth bared. "Savage!" he shouted at Tipoana. "Heartless savage! Dead, brave boys! They deserve respect!"

"Let it be, Tipoana," Antônio Paciência said. "They fought and died like men, did they not?"

The object Tipoana dangled in the lantern light was a crudely fashioned false beard. Every boy in this trench had strapped one of these to his jaw hoping to make the macacos think he was a man.

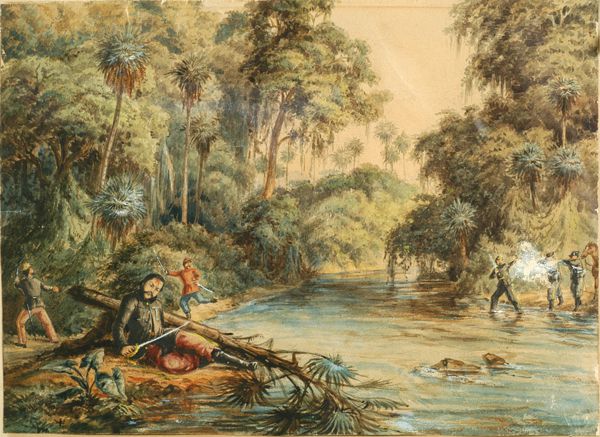

Francisco Solano López eluded his pursuers for six months. Deeper and deeper he fled into the wilderness, through swamps and jungles where no man before had tread, leaving in his wake the bodies of his followers dead from starvation and victims, too, of final purges of suspected traitors. On March 1, 1870, El Presidente, who had been declared an outlaw by a provisional government at Asunción, was at Cerro Corá, "The Corral," a deep, wooded basin surrounded by hills, 230 miles northeast of Asunción. With him were five hundred emaciated men and boys, the last warriors of Paraguay.

And here, too, in this wild and lonely amphitheater ringed by hills, was Eliza Alicia Lynch: Through the roar of guns at Humaitá, the retreat in the miasmal Chaco, the defeat at Itá-Ybate, the last days at Piribebuy, through it all, Eliza Alicia Lynch had stood by the man she loved. She was here at Cerro Corá, hoping against hope, with her five sons from Francisco beside her.

The Brazilians attacked at 7:00 A.M. They sent a cavalry regiment to punch a hole in the ring of hills; outside The Corral, they had eight thousand soldiers waiting.

"For the love of Christ, Eliza! Go! Go!" El Presidente ordered. "Take our boys! Go!"

Eliza rode off in a carriage with four of her sons. The fifth led her escort: fifteen-year-old Colonel Juan Francisco López.

The Brazilian cavalry swept away the guard post in the hills and poured into the basin. One hundred horsemen crashed through the undergrowth toward Madame Lynch and her sons.

"Halt! Halt!"

The driver of the carriage reined in the jaded animals hauling the vehicle.

"Surrender!"

"Never!" Colonel Juan Francisco López raised his revolver and fired a shot. An instant later a lance driven into his chest mortally wounded him.

The battle at the camp of Cerro Corá raged fifteen minutes. The Brazilians went to work with carbine, saber, and lance, shooting and cutting their way through the ragged lines of four hundred defenders. The enemy drew ever closer to El Presidente on his white steed in the heart of the camp.

A lancer spurred his charger's flanks, and with an iron grip on the shaft of his lance, stormed toward Francisco Solano López. His long blade slashed El Presidente's abdomen, but López stayed on his horse as his assailant burst past him. Several of his staff saw what happened and closed in protectively. With the lines of defenders smashed, this small group made a run for it with their chief, cutting their way through the Brazilians and fleeing into the forest. They got as far as the steep-banked Aquidaban-Niqüí, a mile or two north of the camp.

López was bleeding profusely. His horse splashed through the shallow stream. López could not make it up the high bank. Some of his staff helped him off his horse; some sped in search of an easier crossing.

Brazilians who had given chase found the marshal president there, sitting in the mud next to a small palm.

"Surrender!"

He said nothing. With what strength he had left, he flung his sword at the group of macacos.

A Brazilian stepped forward and shot him at point-blank range.

Francisco Solano López then spoke his last words: "¡Muero con mi patria!" ("I die with my country!")

There never was a truer epitaph.

In five years of war, ninety percent of the men and boys of Paraguay were slain. Paraguay, the land of the Guarani, was dead.

At Rio de Janeiro, they counted the cost of the greatest war between nations in the Americas.

The Allies lost 190,000 men, the majority of them Brazilians.

Even so, at Rio de Janeiro, it was the hour of triumph for Pedro de Alcantara, emperor of Brazil. Like his ancestors who had sent their soldados from Lisbon to smite the Infidels in India and subject the savages in Africa and Brazil in the glorious age of As Conquistas, Dom Pedro Segundo had made his conquest.