Excerpted from Brazil, a novel by Errol Lincoln Uys

"Descriptions like those of the war with Paraguay, particularly the battle of Tuiuti, do not find in our literature any rival capable of surpassing them and evoke the great passages of War and Peace rather than best-sellers of current extraction. " -- Wilson Martins, Jornal do Brasil

NOVEMBER 1867 - MARCH 1870

By the spring of 1867, the Allied generals chose their words carefully when speaking of the foe. "I expect to do a thing or two," said Field Marshal Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, marquês de Caxias, who served Dom Pedro Segundo as minister of war and took command of the Brazilian forces after the disaster at Curupaiti. Caxias was sixty-four years old when he got to Paraguay in November 1866, boasting a reputation as a skillful tactician and organizer who had not lost a battle since graduating from the military academy at Rio de Janeiro at the age of eighteen.

With the Brazilian fondness for grandiose sobriquets, the field marshal was called "O Pacificador" in honor of his triumphs, especially in suppressing revolts against the empire. Gray-haired, with a bristly white mustache, slightly hooded eyes, and sharp features; Caxias was endowed with a strong, spare physique and the stamina of a man twenty years younger. The field-marshal had need of all his energy for the tasks he found awaiting him upon landing in Paraguay at the end of 1866.

After Curupaiti, where thousands were slaughtered, the heartsick survivors had slogged back through the carrizal with the wounded. Their demoralization had swiftly spread to every quarter of the Allied front.

Among the fifty thousand men waiting below the miasmal Bellaco esteros were thousands of "voluntários" here against their will, both those who had come as slaves and the wretched of the sertão herded out of the caatinga in irons. Many would have deserted but for the fact that thousands of miles separated them from their hometowns.

There was another sinister aspect to the malaise that was wearing down the Allied army: Brazilians and Argentinians were stationed along different sections of the front, but word of insolence from either group and bloody fights erupted between them, the streets of Paso la Patria not infrequently a battleground for mobs of violent Brazilians and Argentinians.

Above all, there was the loathsome terrain occupied by the Allied army. The river below the morasses, Bellaco Sur, had become a torrent in the rainy season; the water table of the marshes had risen; campsites had been engulfed.

Inevitably, there was sickness. Cholera and typhoid fever became the true enemies. Early in 1867, the daily toll was three hundred. By May, no fewer than thirteen thousand men were in hospitals.

The Allied command was in theory still shared by Bartolomé Mitre, president of Argentina; Venancio Flores, the Uruguayan, who had only a few hundred men left under his command; and, now that he had taken over the Brazilian forces, the marquês de Caxias. In practice, Caxias was virtually supreme commander, for Mitre was suffering most of the recriminations for the losses at Curupaiti, and Venancio Flores was called back to Montevideo to deal with one of the perennial disturbances between Blancos and Colorados.

Field-Marshal Caxias spent six months reorganizing the army, which was now predominantly Brazilian. Base camps like Tuyuti were cleaned up and their fortifications improved; telegraph lines were laid and buried below earth; a serious attempt was made to map the enemy's positions.

Caxias restored discipline and improved morale, and by July 22, 1867, had thirty thousand men ready to move for the encirclement of Humaitá by land. General Manuel Luís Osório, who had led the initial landings in Paraguay, commanded a newly formed Third Corps. For three months, Osório's men slogged northward, cutting almost fifty thousand yards of trenches and establishing batteries all along their twenty-eight-mile route. By late October 1867, they had swung toward the west and were in sight of the Rio Paraguay. On November 2 they captured Tayí, a small riverside post fifteen miles north of Humaitá.

But November 2 was also the night Marshal López chose to send eight thousand men through the esteros to destroy the Allied First Corps at Tuyuti.

November 2 was a Saturday, All Souls' Day. Morning Masses at Tuyuti offered prayers for those in Purgatory, but by nightfall the dead were forgotten amid a carnival atmosphere around the comércio, where sutlers plied the ranks with cachaça and other promises of blessed oblivion and escape from the drudgery of duty in the trenches and redoubts.

Tuyuti's High Command kept sedately to their quarters, playing cards or relaxing with their brandies and port. Another group of Brazilian and Argentinian officers, at peace with each other this night, were gathered in an open-sided mess tent at camp headquarters. Young men and old; regular army, Guarda Nacional, and voluntários - this crowd's behavior was anything but sedate, with garrafas of liquor passing quickly from one hand to another. Smoke from a battery of thick black cigars lay banked up in the yellowish glare from oil lamps.

Firmino Dantas da Silva - Capitão Firmino Dantas - and his cousin, gunner Clóvis Lima da Silva, were among the officers in the tent. They sat next to each other at a table to the right of a dance area where twin sisters, Sabella and Narcisa, morena girls from the Bahia, were performing. They had wavy brunette hair, ruby lips, green eyes that laughed, teased, invited; their cinnamon flesh was warm as the tropical night. They wore V-necked white lace blouses, which scarcely contained their full breasts; their dark red satin skirts swirled against their swinging hips.

Two black soldiers, their khaki drill uniforms soaked, sat to one side, their hands a blur above the drums they played in accompaniment with three guitarists. A lancer from Rio Grande do Sul rose and joined the morenas in dance.

The girls laughed and exchanged bawdy quips with the lancer as they moved their bodies to the beat of the drums. A procurer of prostitutes at Salvador had transported them here a year ago.

Clóvis's eyes followed the girls across the dance floor. Firmino Dantas melancholy gaze was more reserved.

Firmino had returned to Tuyuti in July 1867, a few weeks before the Second and Third Corps' drive to the north and west. Firmino still served on the staff of the quartermaster-general and had been promoted to captain, for he had done good work at Itapiru's stores.

Firmino had a packet of letters now from his fiancee, Carlinda, and from Ulisses Tavares. "Come back to Itatinga," the barão had written this past April. "You have done your share, Firmino. Come home, to the honors you deserve!" That Ulisses Tavares should make this appeal had come as no surprise to Firmino. His grandfather's expectation of a swift, victorious campaign against a barbarous foe had to seem lunacy now viewed within the slow murderous reality of a conflict claiming thousands of Brazilian lives and costing the empire sixty million dollars a year.

Earlier tonight, Firmino and Clóvis had gone for a walk along the perimeter of the citadel. Major Clóvis had been at the base since May 1866, commanding a battery to the right of Tuyuti's first and second lines of trenches.

Stocky, muscular, his Tupi heritage discernible in his broad face, Clóvis da Silva was imbued with the brazen spirit of his bandeirante ancestors.

"The Guarani still hear the Jesuits preaching about devils from São Paulo. I don't know how long their resistance will last. Whatever it takes, however great our sacrifice, in the end, we will conquer them."

"Conquer, Clóvis? Or exterminate?"

"Either way, cousin . . . either way, Brazil will triumph."

Firmino had not doubted, when Brazilian territory was invaded, the just cause of the war, but talk of exterminating the Paraguayans made him wonder if this conflict was to bring honor or shame to Brazil.

Firmino agonized over such concerns. Yet, his anxieties over a protracted war and his own personal fear of combat had not driven him away from Paraguay. Ulisses Tavares had called him home, but still he remained.

For the first time, Firmino Dantas found himself free of the patriarch who had ruled his life since childhood. Free to daydream about his inventions, to indulge his musings about technology, to fantasize about the Swiss girl, Renata Laubner.

Firmino had even considered confessing to the barão his passion for Renata, but after several attempts at writing to Ulisses Tavares, he had thought better of it and kept his love a secret.

Firmino had been less discreet with Clóvis da Silva. "When I return to Tiberica, she'll be mine," he had said to his cousin.

"Carlinda Mendes will be there, Firmino." "I'll be honest with Carlinda."

"Dream all you want, Firmino, but when you go back to Itatinga, you'll take Carlinda Mendes in your arms and be happy with your bride."

In the mess tent, as they watched Sabella and Narcisa, Clóvis suddenly turned to Firmino: "Why so sad, cousin? Sick with longing for your princess? Jewels flutter before you, but do you see them? You're blind, Firmino, stricken with the old sickness."

"And what may that be?"

"Ah, such a malady! The sickness that's raged like an epidemic ever since the Portuguese came to Brazil: our craving for El Dorado!"

"But Renata Laubner is there, Clóvis. She sleeps this very hour at Tiberica, her crown of golden hair upon a satin pillow."

"Yes - at Tiberica! And here, Firmino - tonight? With one of these jewels fluttering between your fingers?"

"One jewel? Compared with the treasure I seek?"

"Ah, dreamer, a drink, then. To your golden princess, cousin Firmino - El Dorado of your heart!"

At daybreak on November 3, 6,500 Paraguayan infantry and fifteen hundred cavalrymen who had crossed the Bellaco esteros in the dark fell upon Tuyuti base. The first line of trenches, manned by Paraguayan exiles, deserters, and prisoners compelled to serve the Allies, fell to the attacking brigades in minutes. At the second, defended by Argentinians and Brazilians, the few companies who stayed at their posts were slaughtered and the mass of defenders hurled back toward the comércio.

Major Clóvis da Silva was at a redoubt to the right of the trenches to which he had returned the early hours of November 3. The artillerymen were taken by surprise: At the alarm, seven hundred Paraguayan cavalrymen leapt from their ponies and were on the earthworks with swords drawn as the gunners poured out of their tents and shelters in total confusion. At 6:30 A.M., half an hour after the Paraguayans had left the esteros, the redoubt surrendered; twelve officers and 249 men were taken prisoner.

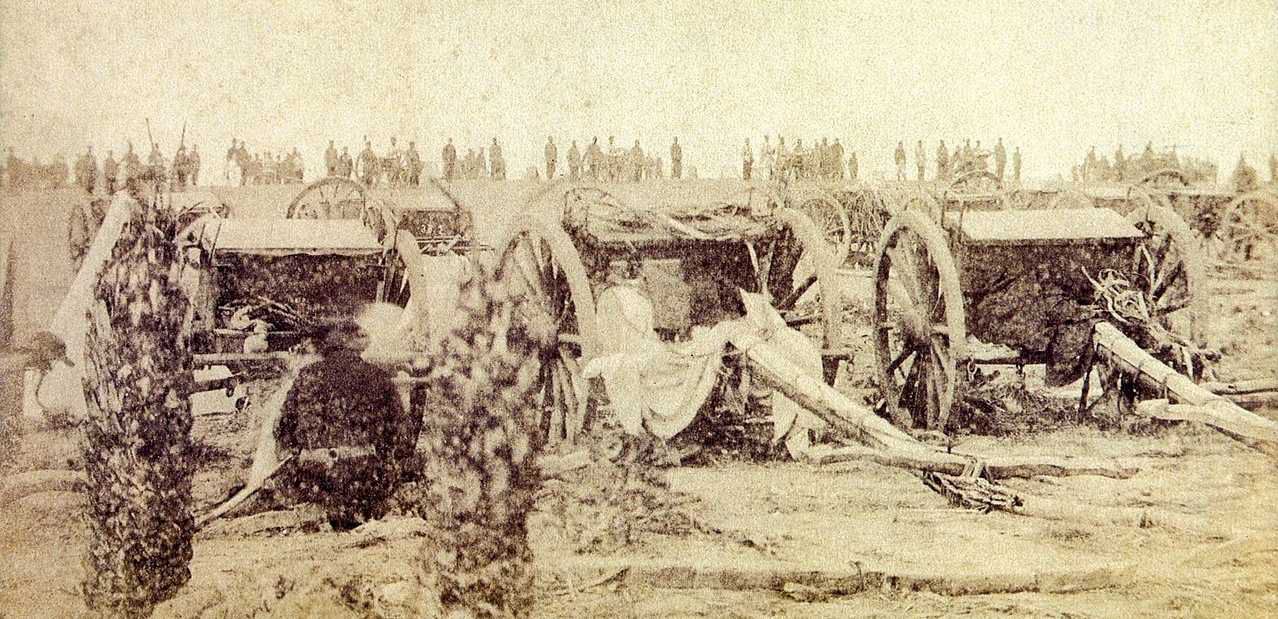

By 7:00 A.M., Tuyuti base lay beneath a pall of smoke from blazing stores and destroyed powder magazines. Hundreds of Allied soldiers fleeing with the horde of camp followers did not stop running until they reached the banks of the Upper Paraná, three miles to the south. Others streamed into the citadel, where they sheltered behind the earthworks, waiting for the next enemy onslaught.The attack did not come immediately, for the Paraguayans had halted at the comércio.

They went berserk there, plundering the wagons and stores, swilling garrafas of liquor, stuffing their mouths with handfuls of sugar, fighting one another for dainties they had not seen before, gnawing at raw artichokes and rock-hard English cheeses.

The rampage cost the Paraguayans dearly, for it gave the battered garrison an opportunity to regroup. At 8:00 A.M., Brazilians and Argentinians counterattacked from the citadel and other positions, engaging the Paraguayans in ferocious hand-to-hand combat.

By 9:00 A.M. the second battle of Tuyuti was over. The Paraguayans streamed back through the esteros, leaving twelve hundred dead and the same number wounded. The Allies claimed victory, but they had lost two thousand men and their garrison was a smoldering ruin. The Paraguayans took fifteen Allied guns back to Humaitá and many captives, including Clóvis da Silva.

Firmino Dantas da Silva relived every agony of his first battle. He rushed like a madman toward those very Yatai palms where he had cowered during the earlier battle. One hundred yards from the trees, he was cut down by Paraguayan soldiers, two bullets buried in his flesh, a machete wound in his shoulder.

Firmino Dantas was carried back into the citadel, among hundreds of wounded, and, miraculously, survived. But his trials in Paraguay were not over

Four days after the battle, Firmino was moved from a field hospital to the base at Paso la Patria and placed in a tent ward with thirty officers from Tuyuti. He felt immensely guilty among these men, who greeted him as a brave man among brave men. His first night he lay awake listening to others cry for mother, for God, for water.

At daybreak, two orderlies moved from cot to cot dispensing mugs of coffee and checking names against a list prepared for the surgeons. An hour after the orderlies had completed their rounds, Firmino was dozing fitfully; he sensed someone approach his cot and opened his eyes to see one of the surgeons standing beside him.

"Firmino Dantas da Silva?"

He made a slight movement of his head in acknowledgment.

"From Tiberica? The fazenda of Itatinga?"

"Yes."

The surgeon gave him a friendly look. "Relax, Capitão, I'm not here to take you to the operating table."

"You know our vila? The barão?"

"I'm told it's a fine town. You'll soon be back there, Firmino Dantas."

"And your name, Doctor?"

"Cavalcanti," he introduced himself. "Fábio Alves Cavalcanti. I'm from Recife."

"There were ninety-two voluntários in Tiberica's company, Doctor," Firmino said. "Oh, God, so many are dead. . . ." Pain in his arm caused him to wince. "Which one told you about Tiberica, Doctor?"

"Not a voluntário, Firmino Dantas. One of Dona Ana's girls. A perfect angel from your Tiberica - Senhorita Renata Laubner."

"Renata . . . Renata." An inner voice had told him it was Renata Laubner, yet he repeated her name with disbelief.

"The daughter of apothecary Laubner. Golden hair, blue eyes . . . a lovely girl. Surely you remember her, Capitão?"

"Renata . . . in Paraguay?"

"At Corrientes hospital. She's been there for six months, since May," Cavalcanti said. "Senhorita Laubner is a wonder. However foul or tedious her duties, you'll never hear a complaint. Oh, she's brave, that girl! I've seen men reduced to tears of gratitude when she bathes their wounds or wipes their fevered brows. A gentle word from her and their courage is restored. A perfect angel."

"Yes, Doctor. Senhorita Renata is a rare jewel."

"I must go," Fábio Cavalcanti said abruptly. "I have other patients to attend to. I'll be back, Capitão - to remove the enemy's bullets." He looked happily at Firmino. "I want to hear all you know about the senhorita, Capitão."

All that night, Firmino's fever raged. Several times he cried out for Renata. The next morning, he lay motionless, spent. He could just make out the figure of a nurse in black leaning over him. "Oh, Renata . . ." His parched lips formed her name.

"The fever's breaking. Rest quietly."

As the nurse sponged his face, Firmino saw that she was an older woman, with gray hair.

The woman nursing Firmino was "Dona Ana," Ana Néri, the inspiration for Renata and others who had come to nurse the sick and wounded. Dona Ana had been fifty-one years old, living comfortably at her family holding at Cachoeira outside Salvador, Bahia, when she had caused a stir by publicly volunteering to go to Paraguay as a nurse. The city fathers of Salvador lauded her noble gesture, but despite her plea Dona Ana had been turned down with a polite reminder that the Casa Grande, not the battlefield, was the proper place for a lady of her quality.

Five days later, Dona Ana took passage for Rio de Janeiro, where she badgered the military authorities until they were happy to see her sail for the Plata. Ana Néri had become a legend, not only for her compassion toward both friend and foe, but also for fearlessness in passing through the very fire of battle to aid the wounded, a mission that had brought her the deepest sorrow a mother can know: Following a skirmish near the esteros, Dona Ana had found one of her own sons dead at the edge of the morass.

Lieutenant Surgeon Fábio Alves Cavalcanti had been here since his first experience of war on the blood-drenched decks of the Jequitinhonha at the battle of Riachuelo in June 1865. In early 1867, when thirteen thousand men were stricken with cholera, the army medical corps had appealed to the navy for help, and Lieutenant Cavalcanti was among the surgeons and doctors who had accepted a transfer to the army. He had been at Corrientes hospital until sent up to Paso la Patria four days ago to deal with the hundreds of casualties from Tuyuti.

As he'd promised, Fábio himself removed the bullets from Firmino's right leg and right shoulder and sewed up the machete gash. Firmino's wounds healed slowly, and twice within three weeks he came down with high fevers. Fábio Cavalcanti was responsible for the patients in this tent ward, so that not a day passed without his stopping at Firmino's bedside; besides the routine visits, he came here, too, to talk about Renata Laubner.

Firmino had little to tell Fábio about Renata Laubner: He met her at a ball at Itatinga; he saw her a few times at apothecary Laubner's shop; he remembered her as a lovely girl with a strong, independent spirit. And he loved her dearly, the Renata Laubner of his dreams, but this he did not tell the young doctor.

When Fábio spoke so admiringly of Renata, Firmino listened with envy, yes, but without rancor. He felt a bond in their mutual admiration for the girl.

Firmino and Fabio were almost the same age - Fábio, at twenty-nine, was two years older - and both were sons of old families of Brazil: Fábio Cavalcanti, the Pernambucano, whose forebear Nicolau Gonçalves Cavalcanti had founded Engenho Santo Tomás; Firmino da Silva, the Paulista, a descendant of Amador Flôres da Silva. Pernambucano and Paulista, their families had carved personal empires out of the Brazilian wilderness.

Fábio was the third son of Guilherme Cavalcanti, the present owner of Santo Tomás. One of his brothers was a lawyer; the other lived at the engenho. Fábio him self had stayed mostly at the Cavalcantis' town house since his school days at Olinda. Senhor Guilherme also spent much of the year at Olinda, leaving the plantation in the care of Rodrigo, his eldest son, but neither Guilherme Cavalcanti nor his two sons whose careers had taken them away from Santo Tomás for one moment forgot that the clan's power lay in those green valleys.

Firmino Dantas felt a pang of guilt when he listened to Cavalcanti talk of his family and pictured himself returning to Itatinga, where Ulisses Tavares waited to greet a hero. It would disgust Ulisses Tavares to know that his grandson had quailed before the Guarani.

Firmino left Paso la Patria on December 20, 1867, with other wounded men on a steamer sailing for Buenos Aires, where they would be transferred to a ship bound for Santos. He had been up and walking for a week, and had bade farewell to Fábio Cavalcanti the previous night.

"Thank you, Doctor, for everything."

"I enjoyed talking with you, Firmino Dantas," Fábio said. "There are too many heroes here."

Firmino flushed, wondering if Cavalcanti had somehow learned of Firmino's cowardice.

"Conquistadors!" Fábio added. "They seek a conquest no matter what it costs in blood and suffering."

Relieved, Firmino said, "The war can't go on much longer."

"We were told that when we sailed from Rio de Janeiro three years ago."

On the evening of December 20, the Aurora, the steamer in which Firmino sailed, stopped at the port of Corrientes, where her captain announced they were to anchor for two days. Firmino was often at the ship's railing those two days, but he did not set foot ashore.

Two months later at Humaitá, in the early hours of February 19, 1868, at the Bateria de Londres and other gun emplacements, men and boys waited at eighty-four cannon. Some were battle-hardened veterans, the best artillerymen left in López's army, and to them fell the duty of manning the modern rifled pieces. Some stood ready at a seventeenth-century thunderer, San Gabriel. Child gunners waited gallantly to serve their elders beside cannon the muzzles of which they could reach only on tiptoe.

Four miles inland, strategic points along the network of trenches were rein forced by the bulk of fifteen thousand defenders remaining at Humaitá. Paraguayan scouts had come back through the marshes and swamps to report battle preparations by units of fifty thousand enemy troops now in siege position beyond Humaitá's earthworks.

Major Hadley Tuttle was with the gunners in the Bateria de Londres. Colonel George Thompson had left him at Humaitá to complete an earthwork west of López's headquarters at Paso Paicú on the outer trenches. Thompson himself was across the Rio Paraguay in the Chaco, setting up a river battery ten miles above Humaitá, a work in itself indicative of the increased awareness of the threat to Humaitá in the three months since Luisa Adelaida Tuttle and her parents had returned to Asunción.

Marshal-President López kept up a defiant stance for the sake of the men and boys in the ranks. Mounted on a white horse, he rode with his aides along Humaitá's trenches, stopping often to chat with soldiers and share their jokes about the macacos bogged down beside the esteros. After second Tuyuti, López had ordered campaign medals struck and distributed them to the survivors, a celebration that some - Hadley Tuttle among them - found farcical, for El Presidente himself had instigated the looting of the enemy's camp, a grave error that had cost the Paraguayans many lives.

Publicly, El Presidente continued to show confidence. On his instructions, the slightest damage to his house by the enemy's shells was repaired instantly, so that the Guarani and mestizo ranks who saw the unmarked whitewashed walls would take this as a sign of the great señor's invincibility. But privately, with his generals and top aides, Marshal López accepted that Humaitá could not hold out indefinitely against the enemy.

López and his generals had no intention of surrendering Humaitá outright. Before the Allies could cut them off completely, however, ten thousand men would be withdrawn across the Rio Paraguay into the Chaco, the only route of escape with Humaitá enclosed by land and the enemy fleet stationed below the fortress.

Just past 3:00 A.M. on February 19, Major Hadley Tuttle was with the commander and other officers at the Bateria de Londres, where Tuttle had been given charge of two 32-pounders this night. Hadley Tuttle felt an anticipation of battle keener than at any other time, for, like the rest of the men, he accepted the hour as critical for Humaitá.

For more than a year, the Brazilian squadron anchored in the channels between Curupaiti and Humaitá had thrown thousands of shells at the two positions, but had made no attempt to force a passage beyond Humaitá's formidable batteries. The bows of every warship were reinforced and fitted with protective overhanging spars; patrol boats constantly searched the river as far up as they dared go. But the loss of master torpedoman Luke Kruger had been a fatal blow to the Paraguayan torpedo unit, for Capitán Angelo Moretti and others had been unwilling to risk further hazardous experiments. The channels of the Rio Paraguay were increasingly free of torpedoes; the enemy still had to run the gauntlet of Humaitá's guns, but otherwise the way to Asunción, 150 miles up the Rio Paraguay, was open.

At the 32-pounders in the Bateria de Londres, Hadley Tuttle's glance moved frequently to the gun embrasures and the dark river beyond, straining for the first sight of the enemy. Tuttle did not have long to wait. At 3:30 A.M., with a distant roar, cannon on nineteen ships began to fire against various positions ashore. When they opened their bombardment, most of the ships were steaming along a sinuous bend of the Rio Paraguay that swung toward Humaitá's cliffs and then looped back to the northwest.

A small battery a mile below the Bateria de Londres was first to return the enemy's fire. Then three positions - Coimbra, Taquari, Maestranca - with a total of twenty guns, opened up, and the darkness along the cliff to the south was broken with flash after flash of cannon fire.

The vanguard of the enemy fleet passed through the storm of plunging shells. Their own gun flashes marked their position for the sixteen heavy cannon of the Bateria de Londres, the first rounds of the battery like a broadside from a man-of-war.

Tuttle's gun crews sprang to reload in the haze of powder smoke swirling in the light from lanterns strung along the roof of the battery. Tuttle stepped up to an embrasure and peered out, seeing the flame of guns on the armor-clad corvettes positioned along the Chaco shore. He discerned in the main channel three new vessels of war - gunships that had joined the Brazilian fleet a week ago.

Constructed at Rio de Janeiro, these ships weren't much to look at: Almost oval in shape, 127 feet long, they lay low in the water like squat black beetles. Each was 340 tons, with iron plates nearly six inches thick, this armor backed by eighteen inches of Brazilian hardwood stouter than oak. Alagoas, Pará, Rio Grande - they were named for provinces of the empire. Of a revolutionary design, the first vessel of their kind had steamed to battle and glory on her maiden voyage in 1862 during the U.S. Civil War: the Monitor, victor of the clash with the rebel steamer Virginia.

The Brazilian monitors each had a single oval-shaped revolving gun turret, the Alagoas equipped with a 70-pounder Whitworth, her sister ships with 120-pounders, the guns capable of a 180-degree angle of fire. The monitors had steam up, but were not proceeding under their own power; each was under tow by an ironclad with engines capable of greater knots for the run past Humaitá.

Brazilian shells ignited an ammunition supply and set fire to the brush and trees. A Brazilian corvette close to the cliffs was burning, and an ironclad towing a monitor took a hit amidships, but neither vessel was in danger of sinking.

The guns of the Bateria de Londres kept up a relentless bombardment. The smoke was so dense, Tuttle and his men could scarcely make out gun crews to the far right and left of them. The battery was the prime target of the monitors and ironclads, their shells exploding along its revetment and tearing the earth in the cliff below Londres. One shot passed clean through an embrasure on the right of the battery, where the men at an ancient muzzle-loader had run the gun back on its slides to reload. The blast killed every one of the crew, wounded others close by, and sent a drizzle of blood and brains far up along the line of guns.

The lead ironclad crossed the place where the chain boom lay submerged in the river; it turned to port, steaming toward the north. The ironclad still had to pass two batteries on the northern end of the cliffs, but it was out of range of Londres' guns. The ironclad Bahia, towing the monitor Alagoas, also rode comfortably over the sunken boom.

Tuttle jerked the lanyard of one of the 32-pounders, stepping aside quickly to avoid the recoil as the gun roared out. The second 32-pounder and two other cannon fired almost simultaneously, their shot also directed against the Alagoas. Two shells struck the monitor's stern, with no more effect than before; two projectiles exploded in front of the vessel.

"Damn! Damn! Damn!" Tuttle swore. His uniform was soaked, his jacket clinging to his back. His face was streaked with dust and powder grains.

Minutes later, from off to the right, a man shouted, "The monitor! We've cut the cable, sir!"

Tuttle leapt to the embrasure. In the glow from the blazes along the cliffs, he saw the monitor dropping back rapidly, the third ironclad and her tow passing the small ship. "Hurry, boys! Load!" he shouted. "We can sink her yet!"

For thirty minutes, the Alagoas was under a violent cannonade. Shell after shell struck the monitor, including steel-tipped shot that pierced her plates; missiles burst in the water next to her hull, shaking her from stem to stern and deluging her deck; balls from Humaitá's vintage cannon shattered into fragments against her turret. They were drifting back almost helplessly, for when the tow had parted, there had been low pressure in the Alagoas's boilers.

At the Bateria de Londres, Tuttle and a gunnery sergeant were trying to extract the stem of a priming tube wedged in the vent of a 32-pounder when they heard someone shout "Cease fire!" Tuttle looked up to see the battery commander standing there.

"Cease fire?" Tuttle asked incredulously.

"Stop shooting at the monitor. Watch closely, Major. There are one hundred fifty men out there. They'll storm her decks and take her prize!"

The batteries along the river north of Londres were still shooting at the three ironclads and two monitors, but it was a desultory, futile cannonade. At Londres itself and farther south, the rate of fire also decreased. The sky was beginning to turn a deep gray; the surface of the river no longer flamed with the reflections of battle. Hundreds of eyes stared down at the river now as the flotilla raced to capture the monitor.

One hundred fifty men paddling twelve canoes! Bogavantes, they called themselves; but they gave the word - "paddlers" - a whole new meaning. They stood up as they dipped their paddles in the water to drive their craft swiftly toward the enemy. The lead canoe would cut across the monitor's bows, letting the rope catch against her hull so that as she forged ahead.

"Hurry, boys! Hurry, there!" Hadley Tuttle said breathlessly, as if spurring on his gun crews. The monitor was beginning to move upriver again. "Oh, take her, boys! Take her now!"

A canoe shot past the Alagoas, the rope linking it to a second craft snared by the monitor's bow. The Alagoas surged forward; the two canoes were rapidly drawn up beside her. The first bogavantes made to leap to the enemy's deck as two other canoes raced alongside.

Four canoes managed to put men aboard, but only a handful of bogavantes got within thirty feet of the turret. Two men stormed the pilothouse, striking it with their sabers in frustration at finding it sealed with an iron cover. Other bogavantes fell to their knees at the hatches, tearing at the covers with their hands until bullets from the turret ports riddled them. In less than ten minutes the attack was repulsed, with the Alagoas, her decks littered with the bodies of the bogavantes, dragging along the empty canoes.

It was not over. The commander of the Alagoas now had his monitor under full steam. It would have been easy for them to drop back with the swift current to protection by the line of corvettes, but they had waited for pressure to build up in their boilers.

The monitor's iron bows shattered the wooden craft; her hull rode over the men spilled into the water. Four canoes of bogavantes perished; four escaped into shallows too hazardous for the monitor to navigate.

The Alagoas ended her pursuit and crossed the sunken boom to join the five other ships this gray dawn when the Brazilians forced the passage beyond Humaitá.

Six Brazilian ironclads now operated above Humaitá, and Allied land divisions had been victorious in their simultaneous attack against an outwork two miles north of the garrison. But the Bateria de Londres and the other guns on Humaitá's cliffs still commanded the loop of the river. Across the Rio Paraguay lay the jungle and swamps of the Chaco, which the Allies, once again underestimating their enemy, had failed to secure. During March 1868, López crossed into the Chaco with ten thousand soldiers, taking the best guns from Humaitá and leaving three thousand men, who abandoned Curupaiti battery and withdrew into Humaitá's fifteen thousand yards of inner trenches.

Through the winter of 1868, a cold, miserable four months, the Allies laid siege to Humaitá. The three thousand defenders deceived the Allies into believing their strength to be much greater with such ruses as rows of Quaker guns - leather-bound tree trunks - and a frequent clangor and thud of brass and drums. In July, under fire from Brazilian ships and the Allied guns now higher up on the Chaco bank, the defenders evacuated their wounded and women, for they still had access to the narrow jungle peninsula opposite the fort. On August 5, 1868, Humaitá surrendered to the Allies; it was four days since the men had eaten the last food in the garrison, and two hundred of its thirteen hundred soldiers were unable to rise from the ground, where they had collapsed.

López's new headquarters were at San Fernando, fifty-five miles north of the fortress and about one hundred miles from Asunción. El Presidente had earlier ordered all but essential military personnel to leave the capital; the administration had moved to Luque, nine miles east on the railroad to Cerro León, which had been Paraguay's main military base before the war.

When Paraguayan outposts beyond Humaitá began to fall to the Allies, López and his army left San Fernando and marched sixty-five miles farther north to an area below Asunción, thirty-five miles to the northwest. According to a previous land survey by George Thompson and Hadley Tuttle, it offered the strongest positions for a defensive front. The Paraguayans dug in five miles inland from the small port of Angostura, above the Pykysyry, a narrow river that flowed into the Rio Paraguay.

Beyond the extreme left of their trenches was Itá-Ybate, "The High Rock," an elevated position among the low hills known as Lomas Valentinas, where López set up his headquarters. Some four thousand troops manned the Pykysyry line and Angostura's batteries; five thousand with twelve guns were kept as a mobile reserve to intercept the Allies on their approach to Lomas Valentinas.

In late August 1868, when the Allies finally began to advance north to Asunción, the conduct of the war was in Brazilian hands, with the marques de Caxias commander-in-chief: Bartolomé Mitre was in Buenos Aires; and Venancio Flores was dead, the victim of an assassin's bullet at Montevideo in February 1868.

The Allied commanders decided against a frontal assault on the Pykysyry line, sending their engineers into the Chaco, at a point below Angostura, to forge a passage through the jungle and across the swamps. Seven miles of the road passed through morasses that had to be filled in with the trunks of palm trees laid side by side, but when the engineers were finished in late November, the Allies sent 32,000 men along the route. Ironclads that had run past the guns at Angostura then transferred the soldiers back across to the east bank of the Rio Paraguay, landing them above the Pykysyry line. At the beginning of December 1868, the Allied corps began to move south toward Lomas Valentinas, bent on dealing the death blow to López and his army.

"Here! Antônio Paciência! Here's one! A general? A colonel? A commander-in-chief?" The dim yellow light of a lantern swung low as the man bent down for a closer inspection. "Ai, caramba! Spurs of silver! Gold! O Santa Maria! Bless me! A Cross the size of my hand! Hurry over, Antônio! Hurry!"

"I'm coming."

The man suddenly straightened up and turned around, held the lantern away from him, and peered into the dark. "Padre?" He got no response. "Where is Padre?"

"Behind us." Antônio Paciência carried his own lantern as he made his way slowly across to the man.

"I don't see him."

"He's down there in those trees." Antônio Paciência reached the place where the man was standing. The light from his lantern fell on a dead Paraguayan.

"Look, Antônio . . . I do not lie!" The man had short arms, and with one furious movement, his lantern swinging wildly as he bent down, he tore the gold Cross from the Paraguayan's neck.

Antônio smiled grimly. "He won't run away."

The man placed his lantern on the ground, went down on one knee, and, pulling out a knife, began to rip open the pockets of the man's uniform. "A bullet here." He touched the tip of his knife to the man's chest. "A lance." He pointed to a slash in the abdomen.

The man continued to speak as he worked, complaining about the paltry treasures from the Paraguayan's pockets: a few religious medallions, some pieces of silver, a broken cigar, some loose cartridges. Antônio loosened the silver spurs, consoling his partner with the fact that here at Avaí the ground was thickly sown with enemy.

But the man responded with another grumble: "Brazilians, too! And tomorrow, when the sun rises like fire in the sky? Aieee! We'll work like slaves!" He stopped talking as he saw a lantern moving toward them. "Padre?"

In reply came a distant "Yes."

The man said to Antônio, "As always, late!"

Like the one he called "Padre," this man had a nickname: "Urubu." None was so adept as he in picking his way across a field after battle to find spoils among the dead.

Urubu, a full-blooded native of Brazil, was one of thirty-four Pancurus enlisted as voluntários da patria from a village in the sertão beside the Rio Moxoto, about twenty miles above the Rio São Francisco. Their village had once been a Jesuit aldeia where their forefathers had found refuge, and long before that, these Pancurus had roamed the surrounding caatinga.

Urubu's real name was Tipoana. He was in his forties, a small, vigorous man with straight, pitch-black hair, sparse eyebrows, and no trace of a beard.

Antônio Paciência had met Tipoana after the storming of Curupaiti, where Policarpo Mossambe had been killed. That battle had so reduced Antônio's battalion that its survivors had been sent to other units; Antônio went to the Fifty-third Battalion, which had been organized at Recife, Pernambuco, and included the company with the Pancurus.

Antonio, Urubu, and the man they called "Padre" were attached to the Second Corps, which, together with the First and Third, had advanced toward Lomas Valentinas at the beginning of December 1868. Five days ago, on December 6, the army had come to a narrow bridge at a stream, the Itororó, defended by five thousand Paraguayans. Three times the bridge was won and lost, until a final assault drove the Paraguayans away.

The combat at Itororó had been a prelude to what occurred earlier this day, December 11. The spot where the silver-spurred Paraguayan lay was at the edge of a narrow plateau three miles inland from the Rio Paraguay. Directly below were two rivers, one of which, the Avaí, gave its name to the battle that had raged today across these heights and in the depressions between them: For four hours in an incessant rainstorm, with heaven's roll above the thunder of the guns and lightning rending the skies, 22,000 men had fought here, 18,000 Allies and 4,000 Paraguayans, with no quarter given. The Paraguayan battalions had been annihilated, 2,600 dead, 1,200 wounded, and 200 left to make their way south to Lomas Valentinas. But 4,200 Brazilians and Argentinians, too, went down, among the wounded the veteran commander of the Third Corps, Manuel Luís Osório.

Almost four years since Antônio Paciência had marched from Tiberica, he had participated in every major campaign since Curupaiti, though his role had changed after his transfer to the Fifty-third Battalion: He had been drafted to serve as stretcher-bearer with the Second Corps field hospital.

It was 2:00 A.M. now, and Urubu, Antônio Paciência, and others were still out searching for wounded. They had been busy for nine hours since the battle ended, wandering across this landscape of horrors. Arms, legs, heads, torsos had been scattered by shell blasts; hundreds of men were strewn haphazardly in unnatural positions, their bodies broken and contorted; as many horses littered the area, huge, stiff, with flies swarming upon their warm carcasses.

Urubu had finished with the dead Paraguayan's pockets, but on the Paraguayan's belt he had found a broken leather strap to which a pouch would have been attached, and he was prowling the darkness, swinging his lantern from side to side, as he searched the ground just beyond the corpse.

Padre was over six feet tall, with bony limbs, sloping shoulders, and a spare, angular frame. He bent his head as he walked, holding his lantern to search the ground he covered.

"Ola!" he shrilled. "Ola! I have it!" He stooped and picked up an object. "Is this what you seek, Tipoana?" He dangled a pouch in front of Urubu; there was a distinctive clink as he shook it. "Silver? Gold?" Padre grinned, his huge teeth exposed. He had a long, narrow face with a narrow, hooked nose, his eyes were small and set close together.

Urubu squirmed with displeasure. "Open it! Open it!"

"Calma!" Padre nodded toward the Paraguayan. "Or you'll wake the dead yet!"

Urubu spoke to Antônio: "See? What did I tell you? He strolls up here, late like a grand senhor. The first thing he sees - my pouch!"

" Your pouch?"

"I found him."

"And I found the pouch," Padre said.

Urubu sulked. "Go on, then," Urubu said. "Open it."

"Not much here."

"Look at him! The man was no Guarani beggar!" Urubu said. "There must be more."

There was some money loosely tied in a small kerchief: ten silver coins.

Urubu was visibly relieved. He dug into one of his pockets and pulled out the Cross. "This is worth much more!" he announced.

"To a pagan like you?"

Urubu laughed. "A beauty, isn't it?"

The three made their way back to camp walking a distance apart, holding up their lanterns to light the ground and undergrowth.

Padre's great loves in life were talking, ale, and women. And since he couldn't enjoy the other two at the moment, he talked.

Padre's loquacious outbursts often led to sermons on whatever theme happened to occupy his mind; thus his sobriquet. He was a mulatto, like Antônio Paciência, though light-skinned, and three years older than Antônio. His name was Henrique Inglez, the same as his father's.

An English actor of no mean talent, Henrique Inglez the elder had been in Brazil for forty years, first at Belém do Pará and later at Pernambuco, where he had found acceptance among the gentry of Recife and Olinda. The loquaciousness of Henrique Inglez the son came from an early start on the stage. His father had made him recite love poems for his audiences at the tender age of four. The precociousness had not matured into real acting skill, and his grotesque teeth and rakish looks were a further hindrance. By his early twenties, Padre was a habitual loafer, whom Henry the Englishman had been delighted to see enlisted with the voluntários.

Padre and Urubu had become close comrades of Antônio Paciência in the eighteen months they'd served together as stretcher-bearers. Before coming to Paraguay, Antônio had known only the company of slaves. The images of that day he had stood like a beast for sale had haunted him since childhood; as he reached manhood, the memory of being inspected by the slaver, while still vivid, was but one of many memories that had aroused a burning hatred of his enslavement.

Freedom! How often he had listened to Policarpo Mossambe talk of his great hope - that he would earn his freedom by fighting for Dom Pedro Segundo. If only Policarpo had lived two months longer, till November 1866, to hear Dom Pedro II's decree that slaves with the imperial army in Paraguay were to be emancipated. The law freed 25,000 black and mulatto slaves then serving with the Brazilian divisions and provided the same freedom for all future recruits for the Paraguayan War.

In truth, freedom had not yet come to mean much to Antônio. Nor, for that matter, to many slave soldiers. When their initial euphoria was tempered by the routines of war, they saw that apart from the promise of freedom, their circumstances were unchanged. When thousands were stricken with cholera and other diseases in the summer of 1867, the slaves were reminded that to earn the reward Dom Pedro II was offering them, they had first to survive the jungles and swamps of Paraguay. Liberty was as distant as ever.

But on that August day at Curupaiti, Patient Anthony had climbed down the face of the earthworks and walked toward the spot where Policarpo had died. He would do as others did who paid personal homage to a dear friend: He would mark this place with a simple wooden Cross bearing the inscription "Corporal Policarpo Mossambe - Brasileiro."

Returning to the tent he shared with Tipoana and Henrique Inglez, Antônio Paciência had told his friends of his plan, and asked if one of them would write the inscription on the Cross.

Over the next three days, when Antônio was off duty, he carved out each letter with a knife.

Never before had Antônio Paciência attempted to write anything more than a scrawled "X" next to his name on lists of voluntários da patria. When he was finished, he heated the blade of his bayonet in a flame and seared the letters.

Henrique Inglez had gone with Antônio to Curupaiti, where Antônio had planted the Cross. "Corporal Policarpo Mossambe - Brasileiro," he had repeated several times as he looked at his handiwork. Just as they were leaving, Antônio stepped up to the Cross and ran his fingers lightly over the crosspiece.

"Never again a slave, Policarpo Mossambe," he whispered. "Never again."