Excerpted from Brazil, a novel by Errol Lincoln Uys

"Descriptions like those of the war with Paraguay, particularly the battle of Tuiuti, do not find in our literature any rival capable of surpassing them and evoke the great passages of War and Peace rather than best-sellers of current extraction. " -- Wilson Martins, Jornal do Brasil

APRIL 1866 - OCTOBER 1867

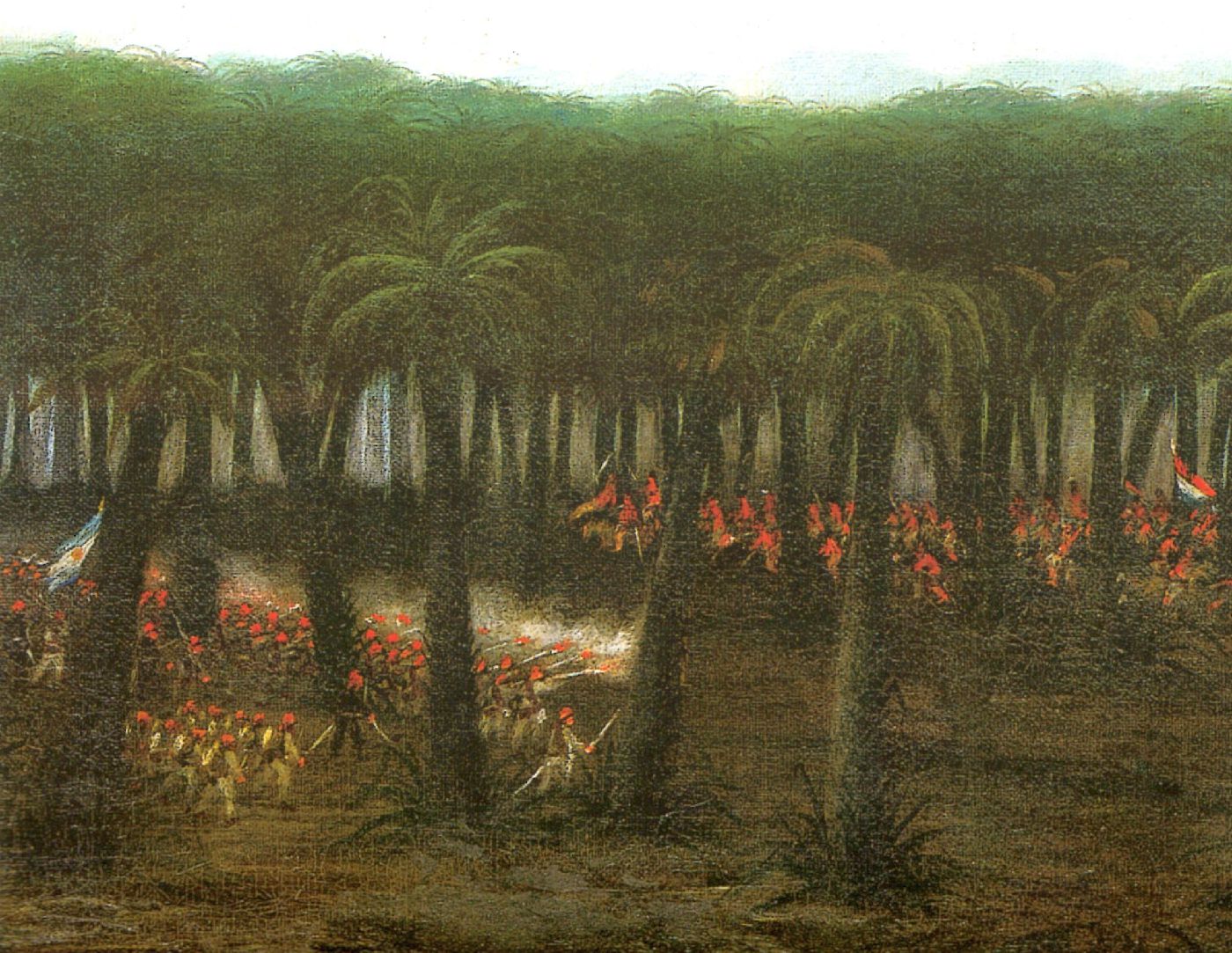

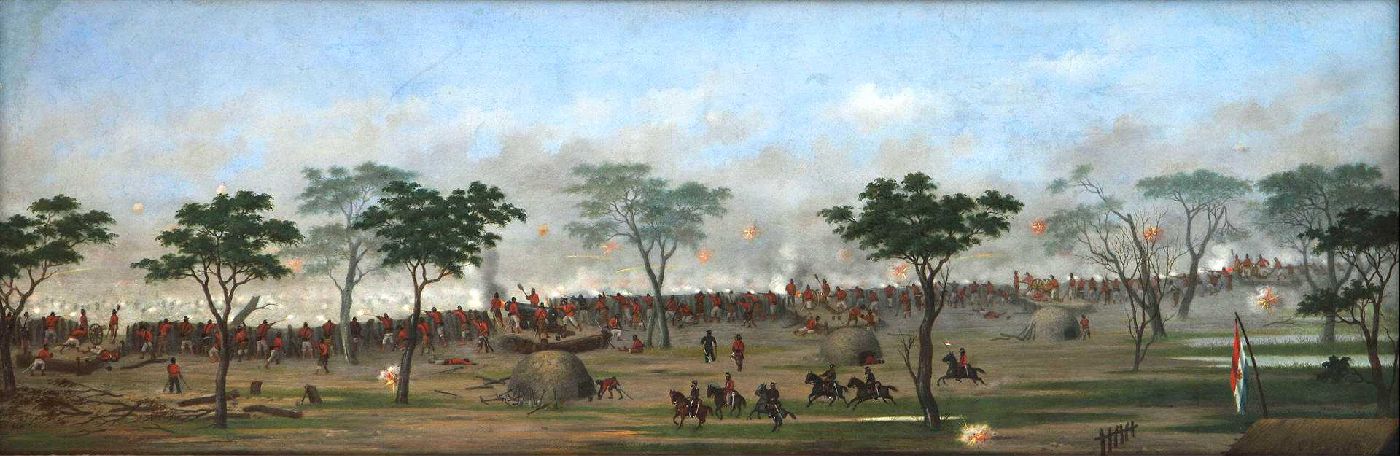

The Tiberica company was in position with its battalion between the Yatai palms, firing down the slope toward the enemy at the edge of the esteros seven hundred yards away. The Paraguayans were closely bunched together as their front ranks sploshed through the morass toward the firm ground in front of the Bateria Mallet and in the direction of the heights with the palm forest. Colonel Mallet's twenty-eight guns went into action with a thunderous oration, but the deluge of fire and iron did not break the red-bloused wave rolling toward the Brazilians.

"Fogo!" Clóvis Lima da Silva commanded the men at the four brass La Hittes, with the earth quaking beneath his feet and bullets whistling and singing over his head.

Colonel Emilio Mallet himself moved among his gunners, with only one order for the line: "They shall not enter here!"

"Fogo! Fogo! Fogo!" came the command, and three hundred yards from the roaring guns, Tiberica's voluntários blazed away at the Paraguayans.

Firmino Dantas was thirty feet behind his men, taking cover at the base of a Yatai palm. With the utmost effort, he manipulated hands that trembled, fingers that seemed frozen as he took out cartridges and caps.

Bayonets flashed and gleamed as the Paraguayans advanced resolutely through the morass. Those up front charged the instant they hit firm ground: The rapid fire from the Bateria Mallet cut them down in bunches, but the gaps were quickly filled.

Firmino Dantas's feelings plunged from terror to hopelessness as he glanced around for a safer place and saw none.

No matter. Within seconds, screaming at the top of their lungs, several hundred Guarani horsemen broke through the extreme end of the Brazilian left flank and came thundering toward the Yatai palms.

Antônio Paciência was no less afraid than Firmino Dantas. He and Policarpo Mossambe and seven voluntários had taken up a position behind a group of low rocks that gave far less protection than the men hugging the earth behind them imagined.

"Load, Antônio! Fire, Antônio! Load, damn you!" Policarpo growled when he saw the young mulatto paralyzed behind a big stone. Antônio obeyed. Mechanically, he pointed his weapon and fired at the mass of men at the edge of the esteros. Then he waited motionless again, his mouth open as he stared at the enemy.

"Baioneta, Antônio! Baioneta!"

Antônio heard Policarpo's command, but he did not obey. Like others, he was transfixed with horror as he saw the Guarani cavalrymen.

Heavy rifle fire from the voluntários brought down the front riders and sent several ponies crashing to the ground. But the voluntários had no time to reload and no place to hide before the thundering, yelling, snorting stampede was upon them, slashing with saber and machete.

With a bloodcurdling yell, a Paraguayan rode at Policarpo, swinging his machete. There was a clash of iron as Policarpo warded off the blow with his bayonet; then he jabbed upward with his weapon, the razor-sharp triangular bayonet biting into the Guarani's cheek, and the man's horse tore away with its screaming stricken burden. A second cavalryman came, and he fell from his saddle as he lunged for Policarpo, who bayoneted him.

But there were few kills like Policarpo's. One hundred voluntários lay dead or wounded beneath the palms; many more had fled toward the Bateria Mallet. The Paraguayans rode on, too, to cover the three hundred yards to the guns, but their ponies stormed into a solid wall of rifle fire from troops massed by General Sampião.

Antônio Paciência looked up shamefacedly at Policarpo. "Oh, Mossambe, I did nothing!" When the cavalry struck, Antônio had clung to the earth behind the rocks.

The Mozambican held out his hand to help Antônio to his feet. "It was the first fight," he said.

Firmino Dantas lay at the palm tree. His face was streaked with blood, his jacket stained crimson. He heard the continuing thunder of battle, but it seemed far away; he heard voices of troops coming up to fill the breach in their lines, but made no effort to appeal for help. Firmino looked at his fingers, which he had pressed against his side. He moaned softly.

A Paraguayan cavalryman lay six feet away. Mortally wounded, this enemy had been hurled from his horse, his body smashing into the palm, splattering Firmino Dantas with blood.

On the Allied right flank, detachments of the seven thousand Paraguayan cavalrymen clashed with a mounted Argentinian regiment, cutting them up and scattering them. Four hundred Paraguayan chargers did not stop, for the rout of the enemy horsemen had cleared the way to a twenty-gun battery. They raced for the guns, with canister and grape emptying their saddles at such speed that only half their number reached the canyon, killing or putting to flight the men who had stayed beside their pieces. The Paraguayans were busy turning the field guns in order to drag them over to their own side when Argentinian cavalry reserves suddenly appeared. Numbers of Paraguayans immediately dismounted to maneuver the guns - they refused to abandon their prizes - and to a man, they were slaughtered.

The Argentinian battery was brought back into action, adding to the cannonade all along the three-mile front.

Nowhere along the Allied line was the Paraguayan assault as ferocious and sustained as against the guns of Emilio Mallet and Antônio Sampião's division supporting the artillery. Wave after wave of the five thousand Paraguayans who had crossed the esteros stormed the Brazilians, breaking to the left and right as they made for the battery or the troop positions at the Yatai palms.

For the Twenty-fifth Paraguayan Battalion - new recruits called to rebuild Marshal López's army - the price of valor was high: The rapid fire from Emilio Mallet's guns was devastating. The next company sent forward discovered that the quagmire had been filled in with the bodies of the men of the Twenty-fifth.

But those troops who broke to the right were able to join up with infantry from the column of nine thousand foot and horse soldiers who had come through the jungle east of the Brazilian positions. The combined infantry made three charges against the Brazilians, driving them deeper into the palm forests. Three times the Brazilians rallied and hurled the Paraguayans back toward the esteros. After almost four hours of fighting, Antônio Sampião himself was critically wounded and one thousand of his men, both regulars and voluntários, were dead or injured. By 3:00 P.M., news of the perilous situation of the surviving defenders was carried to the Brazilian army chief, Manuel Luís Osório.

Osório was known to his men as "The Legendary," a title as well deserved as any baronetcy his emperor chose to bestow upon him. Gathering every man he could detach from his post, Osório hurried to assist Sampião's battered division.

The main body of Paraguayans were in the open between the Yatai palms and the esteros, mustering for another assault on the Brazilian positions. When Osório and his force began to advance, the Paraguayans blasted the front ranks with volleys of musket fire that felled men all along the line.

"Avançar, Brasileiros! Avançar!" Osório commanded, his poncho blowing in the wind, his hand gripping the silver-plated lance he favored as weapon even when afoot.

A bugler running next to Osório was shot dead. Out of the corner of his eye, Osório saw a soldier pick up the cornet. "Sound it, voluntário! Blow!" Osório shouted.

The soldier held his rifle in his right hand; with his left, he raised the bugle to his lips and blew what sounded like the advance.

Spurred on by The Legendary, the Brazilians tore into the Paraguayans with an almighty rage. In fifteen minutes, hundreds of Paraguayans were shot down at point-blank range or bayoneted.

Osório's infantry charge smashed the Paraguayans in this sector. By 4:30 P.M., all along the front, the Allied cannons began to fall silent.

When it was over, General Osório saw the man who had picked up the bugle walking back to camp:

"What is your name, voluntário?"

"Policarpo Mossambe, my General, from Tiberica."

"Take note of it," Osório told an aide. Policarpo had lost his forage cap and Osório noticed the deep dent in his skull. "Where did you get that wound, Policarpo Mossambe?"

"It was before the war, my General. I am the slave Policarpo."

"I saw you fight today, Mossambe," Osório said. "Go back to your company. Tell your commander General Osório says you earned your promotion on the battlefield of Tuyuti. You are to be corporal."

"Thank God you're alive!" Major Clóvis da Silva found Firmino Dantas sitting at the edge of a field of wounded.

Firmino had been slow to accept that he had been splattered by the blood of the Paraguayan cavalryman and not his own. The survivors of the battalion were being regrouped when Firmino had dragged himself to his feet. General Antônio Sampião himself had been there as Firmino returned dazedly to his men. "I'm not hurt," he had said in response to the general's concern. But, seeing the state he was in, Sampião had ordered him to join a reserve company guarding a munitions dump in the rear of the line.

Clóvis, knowing nothing of this, looked respectfully at Firmino Dantas's bloodstained uniform. "If only Ulisses Tavares could see you now, Firmino!" he said, beaming. "You have done him proud!"

Antônio Paciência walked unsteadily beside Corporal Policarpo.

"My Corporal, I was like a worm," Antônio admitted. "I crawled into the earth to escape the enemy. But you saw me, Corporal Policarpo." How he loved the very sound of his friend's new rank. "When they came a second time, I fought."

"Like a young lion, Antônio Paciência!"

It was the day after the battle. Policarpo and Antônio had been drinking cachaça at the wagon of a trader before going back to their encampment.

Antônio saw smoke rising in front of the Allied lines. "What is it?" he asked.

"I don't know," Policarpo replied, frowning. "I heard no gunfire."

They hurried forward, and saw the cause of the fires.

"Ai, Jesus Christ! How terrible!" Antônio cried. "Some are so small and thin, there's nothing to burn!"

The Paraguayan dead were being heaped up in alternate layers with wood, in piles from fifty to one hundred, and set on fire. Of 23,000 sent into battle, six thousand were dead and seven thousand injured. The Allied losses were four thousand. The Place of the Damned had reaped its first harvest.

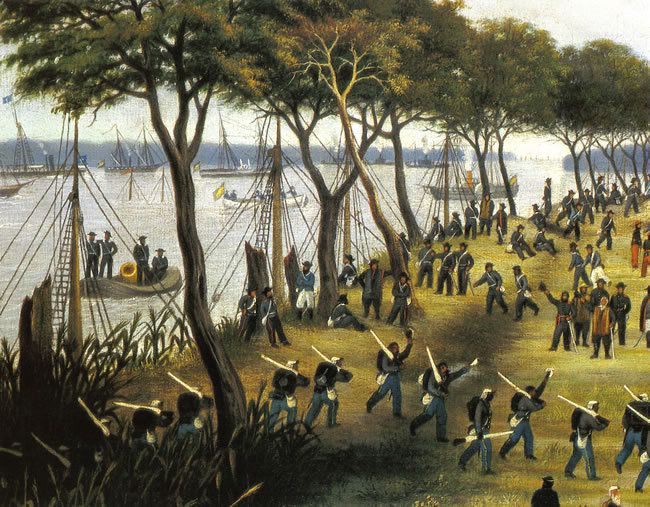

The night was incredibly dark as seven canoes glided swiftly down the Rio Paraguay. Four craft were lashed together in pairs and heavily laden, their gunwales four to five inches above the water. One of three dugouts escorting them rode ahead, two to the rear, the shapes of their crews just distinguishable. It was nearing midnight, August 20, 1866.

"Steady, men. Steady. Let her run with the current," said an officer in the lead canoe.

The craft had come down from a marshy inlet near Curupaiti, an advance battery on the east bank of the Rio Paraguay six miles below the fortress of Humaitá, and were headed toward another earthwork, Curuzu. With thirteen guns in a sunken battery and 2,500 men, Curuzu was the first Paraguayan river defense above Tres Bocas.

All eyes were on the officer in the lead canoe. Before the great war, Capitán Angelo Moretti, former master of the paddle wheeler La Golconda, had navigated the Paraguay under every condition. La Golconda had made her last trip six months ago, with her boilers cold, her machinery irreparable. Towed by the Tacuari, one of three war steamers remaining in service, La Golconda had ended her days in a channel in sight of Curupaiti battery, where she was sunk to impede the enemy's passage.

With his livelihood sitting on the bottom of the Rio Paraguay, the Italian capitán had offered his services to the navy, joining almost one thousand men of a dozen nationalities serving the forces of Marshal López, the majority paid technicians and artisans working day and night to supply war materiel from Asunción's arsenal.

Besides Moretti, there were three other officers with the forty men in the canoes. One was Ramos, a young Paraguayan who had spent several years in England, where he had trained as a munitions expert. Another was a Pole named Michkoffsky, who had arrived penniless at Asunción before the war and had had the good fortune to marry a cousin of El Presidente.

The fourth officer sat amidships in one of the two pairs of canoes lashed together. Lucas Kruger had given scant attention to the navigation of the river. With a big straw hat pulled down low over his forehead and his shoulders hunched, he mostly dozed as the unwieldy craft shot forward, and looked up only when the sailors warned of a rough stretch of water ahead.

The itinerant tinkerer from Pittsburgh, who had promised Francisco Solano López that he could make the Rio Paraguay a damnable passage for the enemy, had done exactly that. Just four months ago, sixteen wooden-hulled steamers and four ironclads of His Imperial Majesty Pedro's navy had sailed up the Paraguay from Tres Bocas for about ten miles, and there they sat, twenty powerful warships kept at bay by Luke Kruger, master torpedoman of Paraguay.

Luke's torpedoes were of two kinds: explosive devices planted in pattern in the channels between the islands and high sandbars from Humaitá to beyond the battery of Curuzu; and those dropped into the river to be carried down to the enemy's ships by the current. Varying in size from 50-pounders to a monster boiler-plated 1,500-pounder, the stationary weapons were anchored so that they drifted four to five feet below the surface; those sent downstream floated attached to barrels or demijohns.

Since the outbreak of the war, Luke had continued his attempt to devise an accurate self-propelled torpedo, but with no success. Three hundred torpedoes were anchored in the river by May 1866, when the Brazilians had finally entered the Paraguay; thereafter, Luke and his men had made regular trips downriver to release floating charges.

The Brazilian warships were guarded by boats that carried long lines with grappling irons to hook the float of a torpedo, which they then towed ashore. They were on station day and night, the night watches the worst as they rowed across the river with only flickering lanterns to help them spot the menace drifting toward them. Young Ramos had recently confused the Brazilians with a diabolical scheme he himself had proposed: sending countless demijohns and barrels bobbing downriver weighted with leather bags filled with nothing more lethal than stones.

On the night of August 20, the seven canoes racing toward the Brazilians carried ten torpedoes in the dugouts that had been lashed together. About a mile and a half above the enemy's anchorage, four islands divided the waters of the Rio Paraguay, with two high, narrow strips of land near each bank and two islands close to the middle of the river. In the dry season, the inner islands were connected by a marsh, which was now flooded.

This was the first time they had used this approach; previously they had re leased torpedoes in the channels to the left and right of the inner islands. Repeatedly the canoes came up against a wall of rushes, a solid, impenetrable mass of vegetation. The sailors waded into the rushes, wrenching them out of the mud by their roots, working a passage through them foot by foot. Mosquitoes and flies and a myriad other pests swarmed around the men, biting and stinging; birds nesting in the rushes scattered; larger creatures, possibly capybara, the great water rats, broke noisily into deeper cover.

It took an hour to break through the rushes. Kruger and Michkoffsky themselves had to climb out to help lighten the craft and drag them through the soft mud. Moretti, who had had the idea of this approach, sat high and dry in his canoe humming to himself as he waited for them.

"Moretti, next time you'll be first over the side," Luke said.

Moretti greeted this with a huge, toothy grin. "I will, Luke?"

"Damn right! With your fancy pants, silver buttons, and all, my lord Admiral!"

Unlike Luke, whose shabby appearance had elicited complaints from none other than Marshal López himself, but who had done nothing to improve it, Moretti wore navy whites and blue jacket adorned with silver buttons bought from a soldier who had stripped the body of an Argentinian colonel killed at Tuyuti.

"I think not," Moretti said. "Our next stop will be opposite the Brazilians."

"Angelo, I hope you're right," Luke said.

Moretti laughed. "Use your paddles quietly now, men," he told his crew. "Not a sound."

Luke gave the same order. His canoe dropped back as Moretti left the open, inundated area for a narrower passage between the rushes.

Fifteen minutes later, Moretti's crew took their paddles out of the water. The dugout rode forward gently, coming to a stop behind a stand of rushes. One after the other, the rest of the squadron came up, drifting slowly near Moretti's canoe.

Through the rushes, the torpedomen could see the lanterns of the boats on guard duty in front of the Brazilian ships.

"Have I ever misled you, Luke?" Moretti asked softly.

Luke Kruger did not reply. He was already directing the off-loading of the first torpedo and float. Before the first pair moved off, other men swam to the opening to check for hazards - a log caught below the surface, for instance, against which a torpedo could strike. After crisscrossing the area several times, the men reported it all clear.

"Easy, boys. Easy now," Luke said. He glanced to the left through the reeds at the distant lanterns flickering like tiny fireflies. "Ramos," he said. "What do you think?"

"Maybe we'll be lucky tonight. Sink one son of a bitch," he said, mimicking Luke.

In the open river behind the rushes, the current was running at three knots, carrying the torpedoes swiftly toward the fleet. A lieutenant with seven oarsmen in a guard boat shouted an alarm when he spotted a float.

A minute later, the lieutenant swung out a line with a heavy grappling hook. The iron claws banged against the side of the barrel float; then the hook plopped into the water. The lieutenant jerked the line; the grappling iron slammed against the torpedo, striking the piston.

A brilliant flash lit up the river behind the rushes. "Mother of God!" Ramos cried. "Luke!"

"It was a guard boat."

"They work! The torpedoes work, Luke!"

"Sooner or later, Ramos," he said laconically.

On August 27, 1866, one week later, Luke Kruger and young Ramos were prepared for another night raid on the Brazilian fleet. Paraguayan scouts operating in the carrizal below the Curuzu battery and toward Tres Bocas reported numerous transports steaming up behind the fleet - indication of an imminent assault against the defenses at Curuzu and Curupaiti.

Luke's plan of attack was different tonight and involved one boat, eight men, including Luke and Ramos, and one five-hundred-pound torpedo. The boat was a forty-foot steam launch that had been captured during the Paraguayan invasion of Mato Grosso in December 1864. The Paraguayans had called this prize "Yacaré" - "Alligator" - but Angelo Moretti had his own name for her: "Lucky Luke."

Moretti was to have gone on this mission, but he'd been summoned to Asunción.

"What for?" Luke asked.

"Perhaps they want to talk about La Golconda.

Luke saw no chance of Moretti being compensated for the steamer that had been scuttled by the navy. "You're wasting your time, Angelo. They did you a favor taking her off your hands."

"It isn't true."

"I worked on her engines -"

"Then you know: They ran like new."

"No, Angelo. It was a miracle you cleared Asunción Bay, but go to Asunción, Angelo. Go. I'll take Ramos."

Luke Kruger shared Moretti's view that the struggle by 525,000 Paraguayans against three nations with a combined population of twelve million was a battle for the very existence of Paraguay.

"López's enemies say they make war on him alone, but the Paraguayans know this is a lie," Luke had said on one occasion. "Buenos Aires has many a score to settle with Asunción. I can accept this. But Pedro of Brazil, who sends his slave horde into battle claiming it's to free Paraguayans from López? Pedro, whose armies slaughter Guarani by the thousands?

"Pedro knows his own future will be decided on the battlefields of Paraguay. If Paraguay defeats Pedro's armies, the Braganças won't last six months. Six months and Brazilian republicans will follow the example of Juarez in Mexico."

"There will be more than an end to Bragança rule," Moretti had suggested. "Emperor Pedro and his slaveholding barons know that your Civil War has doomed that institution in the Americas. To lose the war in Paraguay will be as devastating to the empire as the Confederate defeat. A republican Brazil will not tolerate the continued enslavement of three million people."

This evening of August 27, Luke was alone in the one-room house he shared with Moretti. He had spent most of the day on the Yacaré preparing the steam launch for this night's mission, which he'd modeled on William Cushing's attack on the Confederate iron-plated ram Albermarle in October 1864. The Yacaré would steam for a Brazilian ship with the torpedo lowered into the water. By means of a cable leading back from the spar, the torpedo would be released to float below the ship's hull; backing off, the Yacaré's crew had only to pull a second line to fire the weapon.

As he lay back on his cot, with smoke curling from a cigar, Luke thought of Angelo Moretti on his way to Asunción. He did not believe the Italian's story about being called to discuss compensation for La Golconda. Luke laughed to himself. Truth is, you would rather sail with the devil than set foot in Lucky Luke tonight! Can't say I blame you.

Puffing on his cigar, Luke realized with a jolt that his journey could end here in Paraguay. He had come through many scrapes on his travels, though at no time had he placed himself in as hazardous a position.

A half-hour before he had to leave to join Ramos aboard the launch, Luke got up from his cot and lit a lantern. The yellowish light revealed a sparsely furnished room: two cots, a table, two chairs. All Luke's things were in one trunk at the side of the room. Neatly stacked on top of the trunk were his most treasured possessions - his collection of books. He took up his Bible and carried it to the table. He thumbed through the pages seeking the passage he knew by heart but found more powerful still when read aloud:

"The Lord is my shepherd . . ." He spoke in a strong, resonant tone, and his voice rose as he reached the last verse: " . . . and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever."

Then Luke Kruger stood up. He took his straw hat from Moretti's bed and stuck it on his head. He blew out the lantern and stepped outside, walking briskly toward the bank of the inlet and the mooring of the Yacaré.

The forty-foot launch was painted black to make her less visible to the enemy. Luke heard young Ramos call out that they were ready. Luke waved in acknowledgment, but nearing a plank walkway between the bank and the side of the boat, he glanced toward the Yacaré's prow. Jutting out in front of the launch was a sixteen-foot spar that was hinged to the bow and could be raised or lowered by a windlass; secured near the end of this iron beam was a five-hundred-pound torpedo.

"Cast off, Ramos!" Luke commanded the instant he stepped aboard.

Drifting clouds intermittently obscured a sliver of moon. Ramos conned the launch out of the inlet and into the channel that lay closest to the east bank of the Rio Paraguay on their left. This route passed the batteries of Curupaiti and Curuzu and had not been strewn with anchored torpedoes. If the enemy captains were foolhardy enough to steam up this way, their ships would come under direct fire from the fifty-eight guns at the two earthworks.

Ten minutes after leaving the inlet, the launch was throbbing forward in the lee of Curupaiti battery. Luke stood with Ramos, leaning back against the side of the boat. Ramos had the Yacaré heading steadily down the channel, keeping her in midstream. Two sailors were tending her firebox and boiler; the others were sitting on the deck, checking their rifles - new Enfields taken from Allied soldiers killed in battle.

The Yacaré was passing below the thirty-foot sand-and-clay cliff at Curupaiti when Ramos, who had been talking incessantly since leaving the inlet, said, "I'm happy Angelo Moretti was summoned to Asunción."

"Why, Ramos?"

"I would've stood there watching you leave with Moretti."

"You may yet change your mind."

"No, Captain Luke! I want to be there when you get your son of a bitch -" Young Ramos died with the epithet on his lips.

Riding swiftly down the dark channel with the five-hundred-pound torpedo secured to her spar, the Yacari smashed into the wreck of La Golconda, her stack submerged by the rise in the river. Angelo Moretti would have known of this deadly hazard

Six crewmen were blown skyward by the blast.

And what had been just a passing thought for Lucas Kruger a short while ago became reality. His journey did end here on the Rio Paraguay.

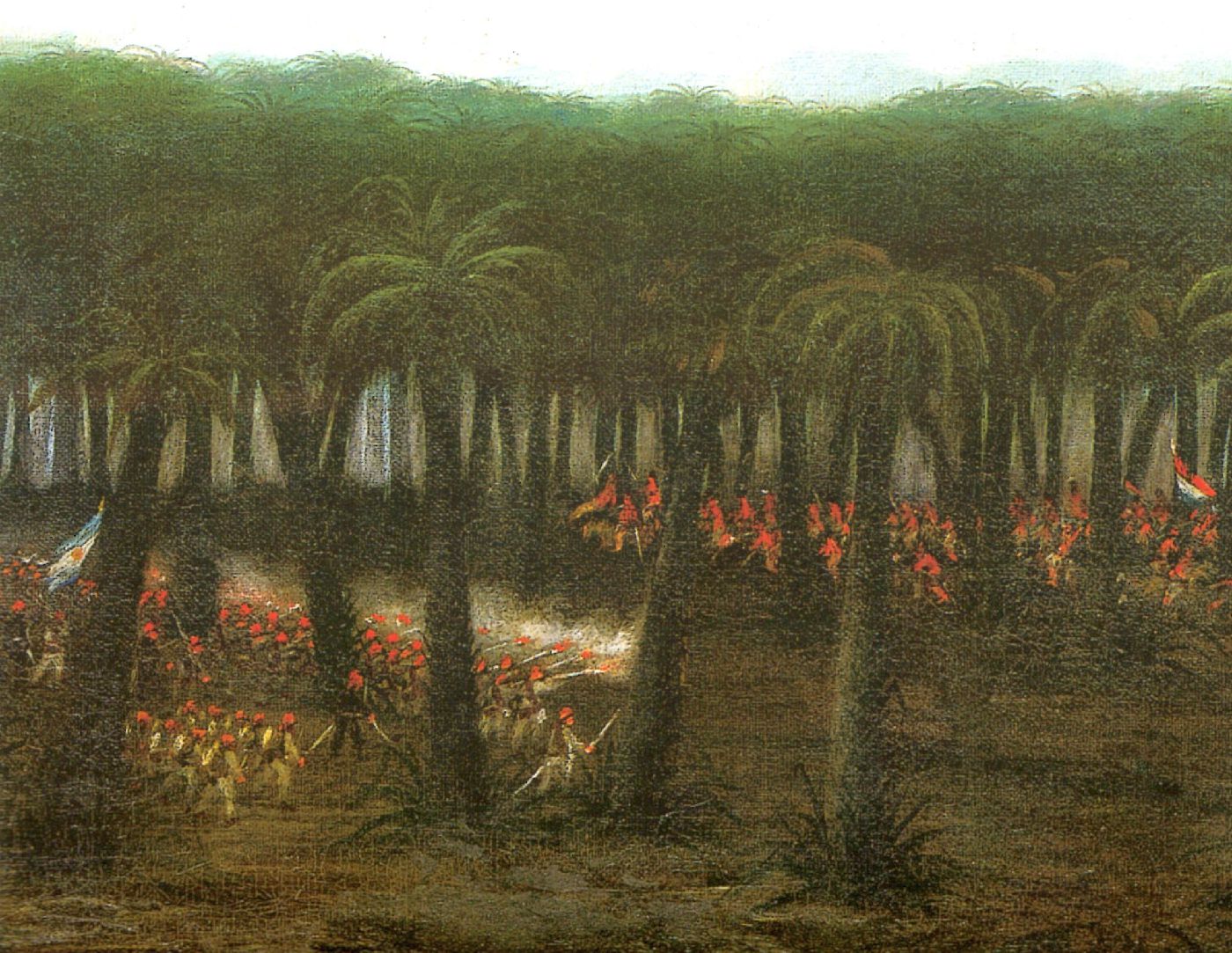

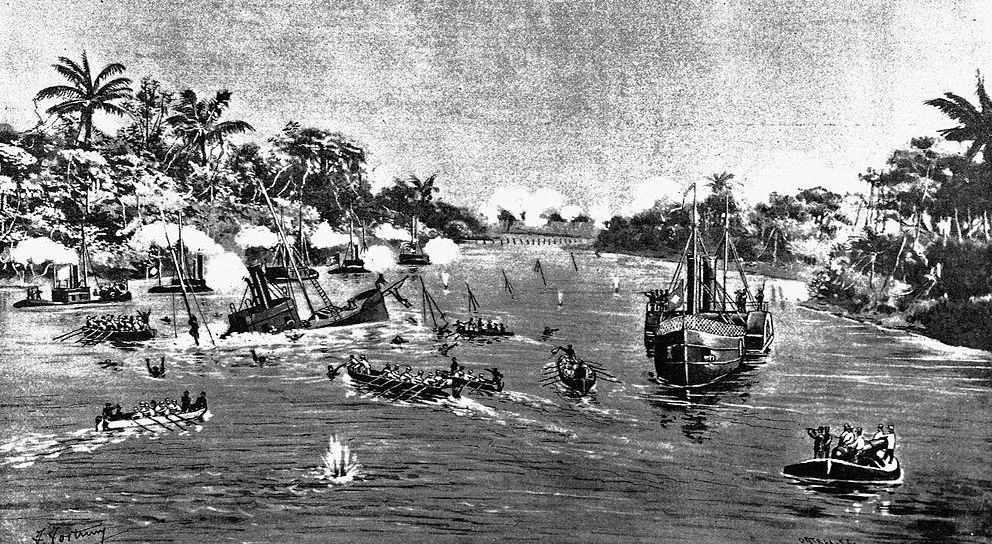

On September 1, sixteen Brazilian ships began to thread their way up the channels of the Paraguay, steaming slowly north toward Curuzu. A smaller squadron provided cover for the transports, which began to land fourteen thousand men on the edge of the carrizal below the Paraguayans' first river defense work. At noon, with most of the fleet within range of Curuzu, an artillery duel commenced between the ships and shore batteries, which lasted seven hours.

At dawn, September 2, the cannonade was resumed. The Brazilians fired more than two hundred shells an hour at the sunken battery of Curuzu, without doing much damage and in return taking only light punishment from the defenders' thirteen guns.

Among the Brazilian ships that had been hit was the Rio de Janeiro. Launched in February 1866, the new ironclad, with four-and-a-half-inch plate and six guns, was one of the fleet's most powerful warships; in the vanguard, she had taken a pounding from the guns of Curuzu, losing a 68-pounder and suffering other damage to her decks. But her commander kept her on station, fighting back gallantly

At 2:00 P.M., the Rio de Janeiro blew up. An anchored torpedo had blasted her poop, and a second had blown a gaping hole near her bow. Within minutes she began to sink.

Master torpedoman Luke Kruger had got his ironclad.

On September 22, the flags of the Allies flew above the earthworks at Curuzu, which had been taken on September 3. With the fall of Curuzu, Curupaiti battery, three thousand yards to the north, was the only obstacle preventing the Allies from attacking the Paraguayan trenches at Humaitá.

For seven hundred men of the Paraguayan Tenth Battalion who had held the trenches on the left of Curuzu, the burden of defeat was terrible. The Tenth had been so outnumbered that they broke rank, leaving only their commander and a few officers, who had been killed. Back at Humaitá, Marshal López had ordered the men of the Tenth to fall in on the parade ground, at attention. When they were assembled, every tenth man in the rank was told to step forward, and the soldiers thus selected were shot in front of their comrades.

At Curuzu, General Bartolomé Mitre ordered an assault on Curupaiti on the morning of September 22. The Allied commander-in-chief's plan of attack involved eighteen thousand men - eleven thousand Brazilians and seven thousand Argentinians -- who would approach Curupaiti from three directions, the bulk of the Brazilian divisions taking the only road between the two positions.

For three days and two nights, torrential downpours had flooded the carrizal, turning the simplest camp duties into feats of endurance. There were guns to be moved up for the attack, and with one hundred men harnessed like beasts to a piece and wallowing up to their knees in mud as they hauled on the drag ropes; there were rearguard trenches to be dug, and companies of sappers worked day and night against tons of earth that slid back into the ditches; there were passages to be slashed through patches of inundated jungle. Just last night, September 21, the rain had finally stopped, and the fleet had been signaled that the attack was on, its preliminary bombardment to commence at 7:00 A.M.

The rolling fire of the guns brought the great army to its feet. The men were tired and hungry and walked stiffly in damp, dirty uniforms, but they reacted quickly enough to the shrieking whistles and bugle blasts. The sun rose; a light breeze carried with it the sweet perfume of the thorny aromitas; the sound of guns played in the background.

The slave soldiers Antônio Paciência and Policarpo, two of forty-seven volunteers remaining from the Tiberica contingent, were attached to a battalion consisting mainly of Pernambucans, Bahians, and other men from the northeast provinces, which were contributing a disproportionate number of volunteers, both slaves and free men. The Tiberica volunteers had been in action once since the battle of Tuyuti, when the Paraguayans again attacked the Allied left flank, in July 1866, an indecisive engagement, but the thousands of Allied soldiers either killed or wounded at Potrero Sauce had brought to an end the days of glory that followed the great victory of Tuyuti.

Firmino Dantas da Silva was not with the Tiberica company. Three weeks after Tuyuti, Second-Lieutenant da Silva had been posted behind the lines at Itapiru on the Upper Paraná, where he joined the quartermaster-general's staff. The slaves from the fazenda of Itatinga - three of the six had been killed - had not seen or heard a word about Firmino Dantas since his taking leave of them.

At Curuzu on September 22, Corporal Policarpo's squad was attached to a section under a caboclo sergeant, Mario Bomfim, whose family were vaqueiros in the Pernambucan sertão north of the Rio São Francisco.

Antônio had told Sergeant Bomfim all he could remember about Jurema, which was not much. "Senhor Heitor Batista and his son, João Montes, sold me to a slaver when I was a child."

"Coronel Heitor Baptista Ferreira and his family? I know the Ferreiras, boy," Bomfim, a scraggy, yellow-faced man in his forties, had responded. "If you cross Coronel Heitor Baptista himself or another poderoso of the family, any one of their hundred armed capangas will make your throat sing like a violin!"

"I can't forget Mãe Mônica," Antônio had said. "I will go back for her."

"Boy! If you set foot on Ferreira lands, know what you're doing: Coronel Ferreira isn't a man to tamper with!"

"My mother is an old slave with not many years left. Why would Coronel Ferreira want to keep an extra mouth to feed?"

Late this morning of September 22, 1866, Sergeant Bomfim and his section were about halfway along the Brazilian column and had to wait ten minutes after the first battalions had started up the road near the riverbank before they themselves began to move forward.

They had covered three hundred of the three thousand yards to Curupaiti, when a deafening barrage drowned the noise from the guns of the Brazilian ironclads. The Paraguayans had forty-nine guns at Curupaiti, thirteen along a concave cliff facing the river, thirty-six covering the land approaches from the direction of Curuzu.

At fifteen hundred yards, Sergeant Bomfim and his section had not lost a man, but were finding it difficult to advance in close order. They went forward a hundred yards or so, through smoke spreading like fog over the carrizal, with the fearsome sounds around them, until they came to a place in the road where a Paraguayan shell had exploded. They broke to the left and the right to pass the corpses heaped up there, and tramped on resolutely.

At one thousand yards, the order came down to move into the carrizal to the right, the snap and crack of reeds and rushes and the oaths of men indicating that hundreds were already pushing through the water-logged marshes to reach positions opposite the enemy's earthworks.

"Right! Keep to the right! Forward! Forward!" officers moving along the advancing lines shouted into the reeds.

"Oh, my God!" Sergeant Mario Bomfim cried when he got his men to the trees.

Two hundred yards away, beyond a broad stretch of earth cleared of trees, was Curupaiti's first defense lines. The felled trees had been piled up along the front of the Paraguayans' earthworks to make an abatis - a twenty-foot-wide, eight-foot-high mass of thickly entwined tree trunks and boughs, every projecting limb fashioned into a sharp stake. Behind the abatis, the earth sloped toward the thirty-six guns mounted on raised platforms to give them the broadest possible range. Their crews used this to great advantage, raking the Allied columns with canister and grape as they came out of the carrizal.

Two Brazilian battalions had come through the morasses to a narrow strip of forest at the edge of the clearing in front of the abatis. To the left, the clearing was strewn with men who had marched ahead of them and had charged toward the abatis; groups of soldiers who had made it across were pinned down behind the wall of tangled timber. To the right, an Argentinian battalion was advancing across the clearing, its officers on horseback, riding between the infantry and rallying them forward. The voluntários saw the Argentinian commanding officer and his horse hurled to earth when a shell burst next to them. Four men immediately went to the colonel's aid and began to carry him back toward the carrizal.

Another shell exploded, leaving a swirl of smoke and dust and no sight of the wounded officer and his four rescuers.

Fifteen minutes later, a colonel with sword in hand gave the order for the battalion to advance: "Forward, Brasileiros! Forward, voluntários!"

Corporal Policarpo Mossambe broke out of the trees and ran forward, with Antônio Paciência close on his heels. Policarpo dodged between stumps and charred undergrowth, shouting for his squad to follow him.

"Up, Brasileiros! Up!" shouted officers to any who dropped behind stumps to escape the storm. "Viva Dom Pedro!" they yelled.

A shell plowed up the earth within thirty feet of Antônio Paciência. The screams of the men caught there mingled with an insane cacophony of shrieks and roars and the hiss and hum of musket balls, the volleys rising in deadly accompaniment to the thunder of the guns.

When Antônio and Policarpo got to the tangled mass of timber, Sergeant Bomfim was already there, with perhaps five hundred others spread out along several hundred yards of the abatis. Some voluntários found places where they could fire at the enemy through the abatis, but a curtain of dust and smoke in front of the trench made it impossible to see the effect of their shots. Some were assaulting the abatis itself with axes, trying to open a passage for a charge against the enemy.

A soldier standing on a log as he swung his ax suddenly dropped the implement:"O Mary, Mother -" He fell back on the ground beside Bomfim, a ball in his chest.

Policarpo Mossambe stepped up to the log. He seized the ax and swung it, sending chips of wood flying like bullets.

"At it, Corporal! At it!" Sergeant Bomfim shouted.

When Policarpo had chopped through a thick limb, Bomfim and the others dragged it away. Policarpo kept swinging at the timbers, tearing off smaller branches with his hand, ignoring the bullets singing over the abatis.

Sergeant Bomfim soon saw how little progress Policarpo was making against the great barrier. "We won't get through this way!" he said. "Set fire to it!"

Policarpo had worked his way about six feet into the abatis. He didn't react immediately to the sergeant's words but continued swinging the ax.

"Policarpo!" Antônio shouted. "Come down! We'll burn it!"

Policarpo had his back to Antônio; he nodded his head affirmatively but raised the ax for one last swing. He froze, with the blade held high.

An instant later, the shell exploded at the front edge of the tangle of trees, hurling Policarpo Mossambe high into the air.

Antônio was stunned by a chunk of flying timber and fell to the ground. "Oh, God!" he gasped, rocking his body, as a shattering pain shot through his head. He opened his eyes: Sergeant Mario Bomfim was lying ten feet away, his brains scooped out and spread on the ground beside him.

"Policarpo?" Antônio mumbled. "Mossambe?"

Policarpo lay at the edge of the abatis, one eye glaring lifelessly, the other mashed in with the flesh and bone of a wound at the side of his face.

A bugler close by was blowing the Retreat. Antônio saw voluntários all along the abatis start back toward the trees. The gunfire from the Paraguayans was intermittent, desultory, but a new sound came from that direction. Maddening to men who had survived the slaughter: the sound of music from Paraguayan bands behind the parapet - saluting the gunners of Curupaiti.

"Fall back!" an officer shouted, running toward Antônio. "Back, voluntário! Save yourself!"

Patient Anthony joined the stampede to the trees and the carrizal beyond.

The full extent of the Paraguayan victory was not immediately known; they could count only fifty-four casualties among their gunners and infantry. When the routed Brazilians and Argentinians were lost from sight in the carrizal, thousands of Paraguayans left their trench, climbing over the abatis and swarming into the clear ing. For hours they worked, bayoneting the wounded enemy, stripping the dead, rejoicing in the gold coin so many macacos carried. When it was over, the Paraguayans left five thousand corpses in the clearing. And two thousand wounded were being carried through the marshes, altogether more than one-third of the Allied army.

"Tu- ru -tu-tu . . . Tu- ru -tu-tu . . ."

The ululation of the turututu horns was a response to the ineffectual bombardment from ten Brazilian ironclads that steamed upriver within range of both Curupaiti and Humaitá. After the rout at Curupaiti, the Allied offensive had bogged down beside the esteros, the first major advance coming nine months after the disaster, with an encircling movement of thirty thousand troops to positions north-east of Humaitá.

Hadley Baines Tuttle, the young Londoner, found the sound of the turututus ominous: After three years of hard service, Hadley Tuttle saw no end to the sacrifices that were being asked of the Paraguayan people. Humaitá and the esteros, reeking with the smell of death, increasingly reminded him of that dire winter of 1854/1855 outside Sevastopol.

Tuttle had been promoted to major and had served these past three years under Colonel George Thompson, the former British army officer whom López had made responsible for the defenses of Humaitá. With seven hundred shovel-wielding men in their engineering battalions, Thompson and Tuttle had directed the construction of 75,000 yards of earthworks - altogether forty-two miles of trenches and fortifications. At Humaitá, eight riverside batteries with sixty-eight guns now flanked the brick-and-stone Bateria de Londres. With Curupaiti battery and artillery positions on Humaitá's outer earthworks, the total firepower was 380 guns, mortars, and rocket stands.

For the two armies ground to a halt amid the steaming jungles and swamps just below Capricorn, summer was murderous: Forty-two miles of Paraguayan trenches either baked in the sun or were raked by torrential downpours; cholera raged, a minimum of fifty men a day carted off to the garrison hospital, and on some days, more than fifty carried out of the wards to mass graves at the cementario.

Hunger was another problem. The scouring of the countryside for new recruits after the carnage at Tuyuti was stripping Paraguay's small farms of labor. The ordinary soldier was in rags, considering himself lucky if he held onto a tattered poncho. And with the dwindling rations, he was growing emaciated. But his eyes still flashed boldly, and when the turututus sounded, he cheered. No matter how great the privation and sorrow to be endured, so long as the marshal-president lived and commanded, the soldier could believe in the ultimate success of Paraguay's cause.

Hadley Tuttle was present at an affair one evening in late October 1867 , during which Francisco Solano López was praising the spirit of his soldiers:

Listen," López said, holding up a hand for silence from those seated near him. The marshal's face was flushed from the brandy he'd consumed after dinner. "Listen." In the distance, the turututus answered a shell from the Brazilian squadron. "Blow, my brave trumpeters!" he declaimed. "Blow, my sons, like the valorous three hundred of Gideon, champion of farmer warriors. Let the Brazilians hear you! May they tremble out there!"

The group with López this night were gathered in the house of Madame Eliza Lynch, who maintained a separate residence in the garrison at a respectable distance from her lover's quarters. She was seated at a table with three other ladies at the far end of the room playing whist, a game at which she excelled.

As Hadley Tuttle sat with the marshal, Colonel George Thompson, and two other guests, he occasionally glanced toward the card table with a look of adoration at the young woman on Madame Lynch's right - Luisa Adelaida.

Hadley Tuttle had married Luisa Adelaida in May 1865. López and Eliza Lynch were present because of Madame Lynch's fondness for Luisa Adelaida's mother, Dona Gabriel - one of the few to befriend La Lynch when she arrived at Asunción from Paris in 1855, already pregnant with her lover's child. "They are not worth your tears," Dona Gabriel had said once in response to Eliza Lynch's misery at being scorned by the ladies of Asunción. "They reject you because they envy your beauty and intelligence."

After Luisa Adelaida's marriage to Tuttle, Madame Lynch had often invited the couple to her entertainments, for they were a lively and handsome pair. Of course, Major Hadley, like other officers present this night, was beginning to show the strain of three hard years. His uniform was clean but shabby, with a patch on one arm and a tear that had been stitched by Luisa Adelaida; and his face was scorched by the sun and revealed lines of worry and weariness as he listened to the marshal.

Three times already, López had sought peace: On the eve of the battle of Curupaiti, the marshal-president had met with Mitre of Argentina; early in January 1867, López had agreed to accept an offer by the United States to mediate an accord; this past August, a British diplomat from Buenos Aires had found López amenable to a peace settlement. Each attempt had failed, for the Allies' demand was totally unacceptable to López: "We will not discuss peace until Francisco Solano López is off Paraguayan soil."

When he met the British diplomat from Buenos Aires in Humaitá this past August, Tuttle had given him letters for his family in south London. Writing to his brother, Ainsley, who had served with him at the Crimea, he had given his impressions of the situation:

Since the start of the war, the enemy has said its belligerence is a crusade in the name of humanity to free Paraguay from a tyrant who rules by terror alone. López is a man to be feared. God knows, I have been within earshot of Asunción jail more times than I want to remember, when the secret police were torturing some unfortunate enemy of El Presidente. But the enemies' claim that the destruction of López is their only objective must be doubted. Their own hands are red with the blood of political opponents they have butchered.

The terms of the treaty signed by Brazil, Argentina, and the Colorados of Uruguay are well known here, including the secret clauses that guarantee Brazil and Argentina thousands of square miles of Paraguayan territory. The Paraguayans believe the enemies' real objective is nothing less than the extermination of their race.

The Paraguayan peasant, unlike his counterpart in Brazil, owns his small parcel of land or rents it from the state at a low price; his children are being educated at schools established in every pueblo; his health is protected with mass campaigns of inoculation against smallpox and with other measures instituted by the English doctors. He sees all this as coming from the despot who rules him and whom he esteems as passionately as his ancestors did the black robes of the reductions. As long as the marshal-president is there, the Paraguayans will continue the struggle, even if their beloved fatherland is left in ashes.

Like his commanding officer, Colonel Thompson, and most of the foreigners paid by López, Hadley Tuttle had chosen to remain in Paraguay, though not without increasing concern for the safety of his wife.

Luisa Adelaida and Dona Gabriel had been at Humaitá for six months, staying with Hadley in a house near Madame Lynch's quarters. Eliza Lynch herself had asked them here to assist in organizing a women's corps. Several hundred mothers and daughters served in the hospital, cleaned the barracks and campgrounds, and cultivated field crops. Madame Lynch was often seen in the uniform of a colonel of the Paraguayan army when she went among the women, who had their own captains and sergeants; they had sent deputations to the marshal-president asking to be drilled as soldiers and allowed to fight, but López had turned down these requests.

At Eliza Lynch's house this October night, Marshal López still believed the enemy could be driven off Paraguayan soil with one more hammer blow like Curupaiti.

López was planning to strike that blow with another attack against Tuyuti, where the Paraguayans had suffered their worst defeat. Tuyuti, now the main supply base for the Allied divisions deployed northeast of Humaitá, could be seen from watchtowers along Humaitá's outer earthworks. López intended to send eight thousand men - sixteen battalions of infantry; six regiments of cavalry - against Tuyuti. "We failed last year because surprise was lost. This time we will cross the esteros at night and be in position before dawn. We will avenge the slaughter at first Tuyuti," López promised.

The guns on the Brazilian ironclads had stopped firing, and the turututus had been laid aside, when the Tuttles left Eliza Lynch's quarters. The silence that followed the bombardment was pierced by the scream of the cicada. Sentinels in the trenches and watchtowers saw the enemy camps and ships frozen in the moonlight, but for most at Humaitá, late night brought a false but welcome peace.

Hadley held Luisa Adelaida tightly on the short walk from Madame Lynch's house to their own place, for they had only a few hours together: In the morning, Luisa Adelaida and Dona Gabriel were returning to Asunción.

Alone in their room, Hadley and Luisa Adelaida spoke in whispers, for the simple interior had makeshift partitions plaited with reeds and thick grass. They made love, knowing that they would have to cherish these moments through months of separation.

The next morning, Hadley escorted Luisa Adelaida and her parents to an embarkation point near Humaitá to board a steamer for the voyage north. A regimental band played as the paddle wheeler that had come down from Asunción arrived at the landing. It was crammed with new recruits. A few were pure Guarani; a few, mulattoes; the majority, of mixed Guarani-Spanish descent. Some were in rags, but most wore their best shirts and trousers or chiripas, loose-fitting gear of a square of cloth draped from the waist and between the legs. A few sported red shirts, white trousers, and military caps - uniforms home-sewn or inherited from fathers and brothers who had not returned. What was common to every recruit, from the tall ones who looked older to little fellows having trouble keeping up, was youth: The youngest of these new soldiers was nine years old; the oldest warrior-to-be, thirteen.