Excerpted from Brazil, a novel by Errol Lincoln Uys

"Descriptions like those of the war with Paraguay, particularly the battle of Tuiuti, do not find in our literature any rival capable of surpassing them and evoke the great passages of War and Peace rather than best-sellers of current extraction. " -- Wilson Martins, Jornal do Brasil

APRIL 1866 - MARCH 1870

In late March 1866, the venerable Guarani general, Juan Bautista Noguera - Cacambo - seventy-nine years old now, small, shrunken, with his hatred of the Brazilians mightier than ever, took great pleasure in a war trophy delivered to Francisco Solano López at his headquarters across the Upper Paraná: a leather bag filled with the heads of nine Allied soldiers.

Cacambo waved his tiny hands and danced with glee at the sight of these enemies. Unsheathing his sword, Cacambo cut the air above the trophies and repeated his vow: "I, Cacambo, will slay the first macaco who dares to leap to our soil!"

An Allied invasion was imminent. The Paraguayan offensive in the Argentine province of Corrientes had been disastrous: Sixteen thousand Paraguayans perished in battles and through sickness before the last units crossed the Upper Paraná back into Paraguay at the end of October 1865.

Paraguayan conscripts had again brought their army up to 25,000 men, most of whom were deployed in camps above the Upper Paraná. Their main base was at Paso la Patria, ten miles east of Tres Bocas. Between these two locations, the carrizal - deep lagoons and mud flats that extended inland for one to three miles - broke the northern banks of the Upper Paraná. At Itapiru, between Tres Bocas and Paso la Patria, there was a battery revetted with brickwork and mounting seven cannon. At Paso la Patria, thirty feet above the carrizal, there were thirty field guns; elsewhere in the jungle along the riverbank, artillery companies were concealed in the woods at likely enemy landing places.

By March 1866 the Allied army of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay was assembled below the Upper Paraná. The Brazilians now had an effective strength of 67,000 men, including 35,000 voluntários da patria. President Bartolomé Mitre, who, in terms of the Triple Alliance Treaty, was commander-in chief of the Allied army during operations on Argentinian territory, headed an Argentinian contingent of 15,000 men. The Uruguayans, led by the Colorado general Venancio Flores, contributed 1,500 men, all they could muster in the aftermath of the civil war with the Blancos.

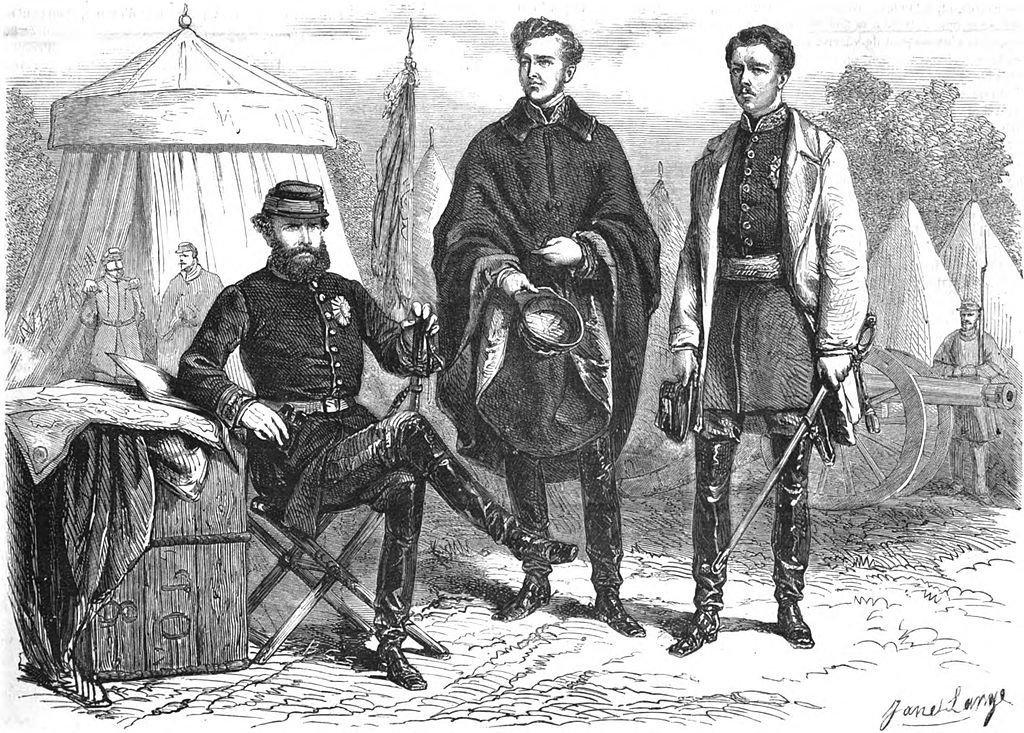

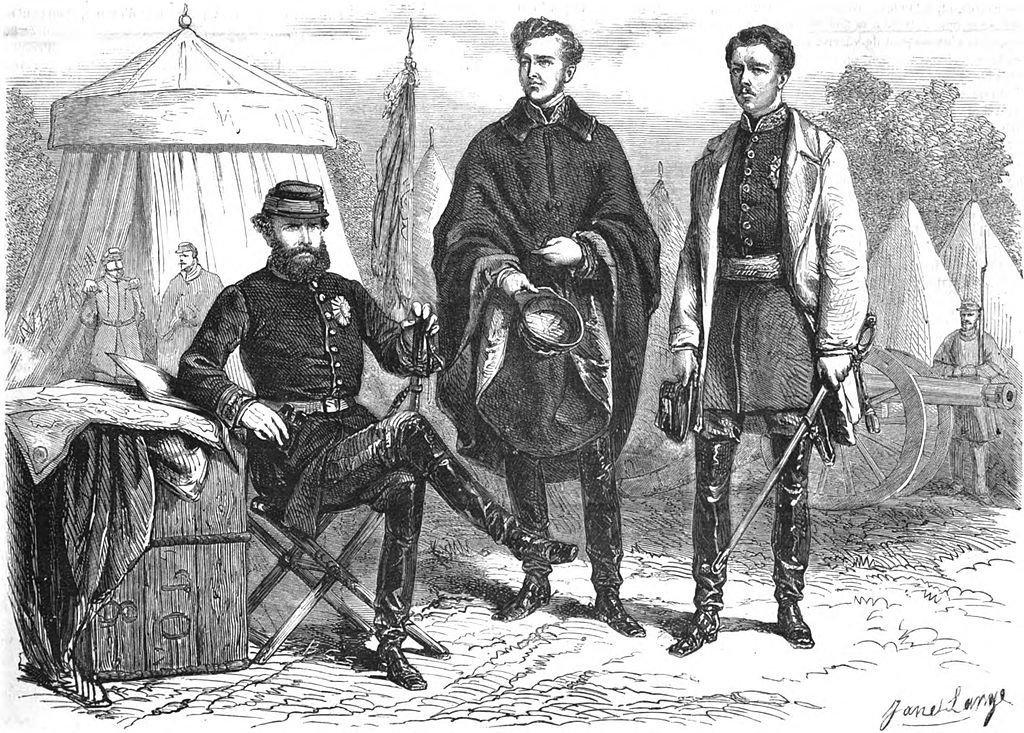

Dom Pedro Segundo had made a brief journey to the seat of war with his two sons-in-law, Prince Louis Gaston, comte d'Eu, and Prince Louis Augustus, duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Traveling by horseback through southern Brazil, the royal trio had been present when a column of 4,200 Paraguayans had surrendered at Uruguaiana in September 1865. The thirty-nine-year old Dom Pedro, imposing as ever with his six-foot-three-inch frame and luxurious golden-brown locks and beard, had been unimpressed by the captured Paraguayans. "An enemy not worthy of being defeated," His Majesty had declared in a letter to a friend.

The ninety-two voluntários of Tiberica, led by Firmino Dantas da Silva, had left the town late February 1865, marching first to São Paulo and then down to Santos, where they had taken passage on a ship with other Paulista volunteers for Rio Grande do Sul. There they had been drilled for four months until July 1865, when they were posted to guard a crossing on the Uruguay River. For eight months they sat here without a glimpse of the enemy and with nothing to break the monotony but news of victories won by others, until they received orders to join the Brazilian First Corps at Corrientes.

In April 1866, the main body of the Brazilian army began to move to forward positions on the south bank of the Upper Paraná opposite the Paraguayan battery at Itapiru. On April 5, an advance group of eleven hundred men with La Hitte cannon and mortars occupied and entrenched themselves on a grassy sandbank separated from Itapiru by a narrow channel. Supporting their landing were eight Brazilian warships.

At 4:00 A.M. on April 10, thirteen hundred Paraguayans launched a counterattack by canoe from Itapiru to dislodge the men on the low spit of land opposite the battery. Within a quarter of an hour, immense flashes broke the blackness of predawn as the Brazilian ships opened fire, the booming guns adding to the din of battle rising from the sandbank.

Only sixty of the ninety-two men who had left Tiberica in February 1865 were present to see the first action since departing their town: The rest had contracted dysentery, smallpox, and other diseases, and of these, fourteen had died, eight were in the hospital at Corrientes, and ten had been sent home unfit for service. Firmino Dantas da Silva himself had spent two weeks in the hospital with measles. He was serving as liaison officer between the battalion and the headquarters of General Manuel Luís Osório, commander of the Brazilian First Corps.

Two Tiberica voluntários watching the flashes of cannon and musketry stood together yelling encouragement to the unseen gunners aboard the Brazilian ships. The enemy's cannon blazed in the dark line of jungle opposite, and shells intended for the warships roared through the air above them, but the two men greeted the Paraguayan shot with derisive laughter. When it began to grow light, they climbed the hillside to reach a better vantage point, though they found the sandbank obscured by thick smoke, the gun flashes less distinct as dawn broke.

The early light showed one of these voluntários to be much older: The man had not yet fought a skirmish with the enemy, but he bore a scar so terrible that soldiers thinking of the battles they must soon face were reluctant to gaze upon it. The old wound lay across his skull, from above his left temple to the back of his head. He had gone completely bald after suffering this awful blow.

This voluntário was Policarpo, one of the slaves bought for Itatinga from the trader Saturnino Rabelo by Ulisses Tavares in January 1856. Policarpo, twenty-nine at the time, had assured the senhor barão that he was a Mossambe whom the lash had taught obedience and hard work.

In truth, Policarpo was lazy, and had resented the regimen of the plantation, particularly at harvest time, when the slave bell rang at 5:00 A.M. for assembly and prayers in front of the mansion before work in the coffee groves until dusk. One morning four years ago, when Policarpo did not respond to the bell, an overseer had rushed to the dormitory, but Policarpo was not there. A search had been mounted immediately for the runaway; with the soaring prices for slaves after the abolition of imports from Africa, even idle Policarpo was a valued possession of the senhor barão.

Policarpo had not run from Itatinga. When the search party set out, he had been less than five miles from the senzala, snoring loudly in a patch of forest beside the road from Tiberica. He had collapsed there in the early hours gloriously drunk, a jar of cachaça and a package of the best Bahiana tobacco beside him. Policarpo detested the work of the harvest, but there had been a consolation: He would occasionally steal a sack of coffee beans from where they were stored in the old fazenda, and trade them to the squatter Gonzaga for a supply of cachaça and tabak and trinkets.

Policarpo had still been befuddled when they found him. His captors tied his hands and made him run back toward the fazenda at the end of a length of rope attached to one man's saddle pommel; when the horse had suddenly jerked forward, the rope flew loose and Policarpo sprang away toward a hill covered with coffee trees. Dashing between the trees, he had eluded his mounted pursuers for a few minutes until their shouts alerted the overseers of a slave gang working on the next hillside. An overseer had arrested Policarpo's flight by striking him over the head with a seven-foot iron bar used for driving holes into the earth to plant seedlings. Unconscious and with his skull indented by the blow, Policarpo had not been expected to survive.

But he had recovered, and had been led to Ulisses Tavares, who closely inspected his wound and questioned him at length. (The squatter Gonzaga had fled Itatinga immediately upon hearing what had happened to Policarpo.) Policarpo had been placed in the stocks, the tronco diabo, and had also been flogged with one hundred lashes. Returned to the coffee groves, he had suffered fainting spells and sudden ravings and was unable to meet his daily quota. The overseers had finally confined him to the terreiro to rake the berries as they dried in the sun.

Policarpo had become tractable, and apart from overindulgence in cachaça, gave little trouble at Itatinga. But other slaves working on the terreiro grumbled about him: It seemed to them that whenever the sun blazed down on the drying terrace and it became unbearably hot, Policarpo would have one of his spells, shaking his head and moaning until he was compelled to seek the shade for a recuperative nap.

There were slaves, too, who wondered about Policarpo, the Mozambican: Wasn't it true that after his head had been broken, Policarpo had risen higher than any man in the eyes of the mãe de santo, the mother of the daughters of the saints? When the drums played, wasn't it extraordinary what energy came to Policarpo Mossambe as he danced for the African deities? And when the spirits descended, wasn't it the feebleminded Policarpo whose lips spoke with the greatest strength?

The young man with Policarpo this morning watching the fight for the sandbank near the Paraguayan shore was the mulatto Antônio Paciência. Patient Anthony, nineteen years old now, was tall and lean, with a tough, spare frame and iron muscles. His nose was slightly aquiline; the look in his brown eyes suggested inner strength; his dark-skinned countenance was frank, an expression often misconstrued as insolent. A good worker, slaver Saturnino Rabelo had predicted, and this was correct: Antônio Paciência had given no cause for complaint about the quality of his labor. Still, he had been a thoroughly bad slave.

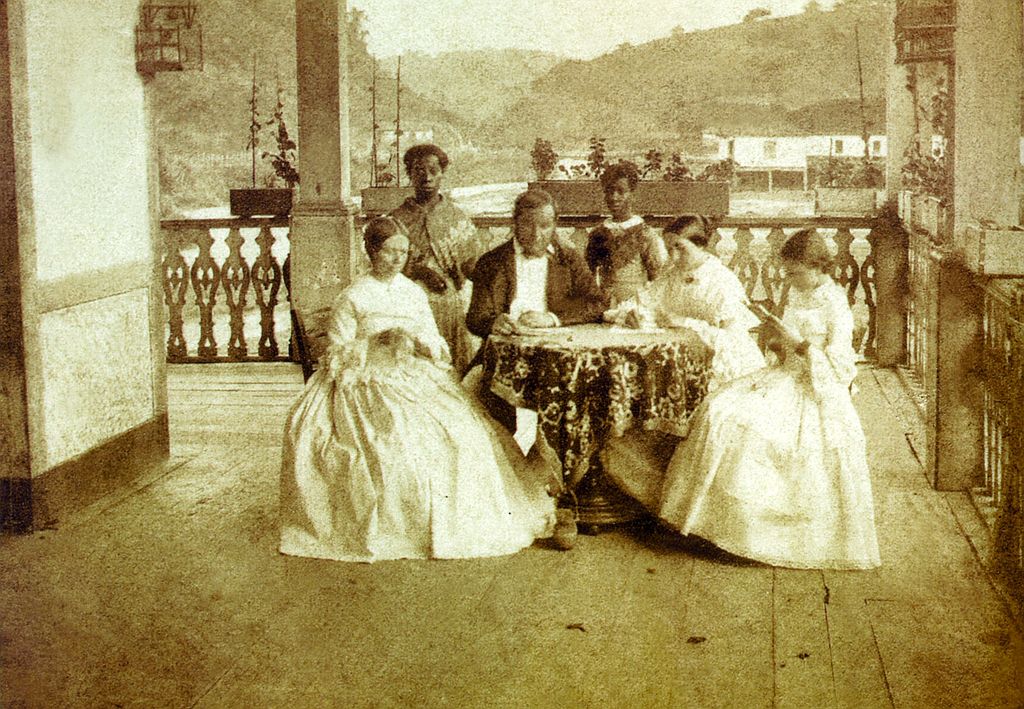

Antônio Paciência could remember the delight of the iaiá - the slaves' corruption of "Sinhazinha" - when he had been given to her. Teodora Rita couldn't wait to show him off when visitors came to Itatinga.

Except for his behavior during inspection by the iaiá's relatives and friends, however, Antônio Paciência had seemed incapable of pleasing the baronesa. Teodora Rita's tongue wagged incessantly with complaints about Antônio Paciência and the difficulty she had training him.

There had been the time the iaiá's silver shoehorn disappeared. Iaiá Teodora Rita said she had left it in a boot given to Antônio for cleaning. The iaiá and Dona Feliciana, wife of Eusébio Magalhães, insisted on watching Cincinnato, the carriage driver, cane him, ordering that the punishment continue, until Antônio Paciência had finally admitted stealing the shoehorn: "Oh, iaiá, forgive me! I put it in my pocket . . . Oh, iaiá, I lost it, I do not know where!" (Months after the caning, the iaiá told Antônio to clean a pair of shoes she hadn't worn for a long time, and as he was carrying them to the fazenda's kitchen, something dropped with a clink to the stone floor. His terror was absolute when he saw that it was the silver shoehorn! Pausing just long enough to pick it up, he crept out of the house and buried the shoehorn far down the slope toward the Rio Tietê.)

Two and a half years after arriving at Itatinga, Antônio Paciência had been ordered to the senzala. He was genuinely puzzled, for there had been no recent clash with the iaiá, certainly nothing as grim as the loss of her shoehorn.

"I'm the slave of Iaiá Teodora Rita," Antônio Paciência protested to the overseer who had been sent to fetch him from the fazenda's kitchen. "I work in the big house.

The overseer, a mulatto like Antônio, had grabbed him by the scruff of his neck. "The senhor barão's wife herself gave the order!"

It took a long time for Patient Anthony to understand that Teodora Rita simply had lost interest in her birthday gift from the senhor barão.

The move to the senzala had been almost as traumatic as being sold away from Mãe Mônica. Cast among the mass of Itatinga's 220 slaves, Antônio had experienced a deprivation that went far beyond being stripped of the nice clothes he had worn on parade in front of the iaiá's guests or denied the food from the fazenda's kitchen.

Chigger Man was the first to bring Antônio Paciência close to understanding the loss of dignity.

Chigger Man, who was said to be more than ninety years old and had served the senhor barão's father in the canoes of the monsoons, was expert in prying loose the tiny mites that attacked the slaves' feet, burrowing under the skin to lay their eggs. Chigger Man performed his crude surgery outside one of the slave dormitories, and Antônio himself had submitted to Chigger Man's knife. Watching the old slave probe and scratch for chiggers had left Antônio with a feeling of revulsion and sharpened his sense of loss at leaving the fazenda.

By the time he was fourteen, Antônio Paciência was doing the work of an adult, for which he was praised by the senhor barão himself. "I was not wrong in listening to Rabelo. You are a good worker. God willing, Antônio, when you are older, you may be an overseer at Itatinga."

Seven months later, Antônio Paciência was given fifty lashes for running away from Itatinga. Eighteen months later he was a fugitive for forty-seven days until he was caught at São Paulo.

Antônio's second flight had been planned with two other slaves. He had wanted Policarpo to go with them, but the Mozambican refused: "The risk is too great."

"We'll go to São Paulo; perhaps to Rio de Janeiro. We won't be found among thousands in the cities."

"Perhaps you'll be lucky."

"Come with us, Mossambe!"

"And lead them to you?"

"We won't be caught."

Policarpo had lowered his head, exposing the deep scar. "Like the mark on a beast," he had said. "Any man who sees it will know: 'Mossambe-withthe-broken-head' - the property of the barão de Itatinga. I cannot go with you, Antônio."

The three slaves had fled Itatinga at the onset of winter 1863. One of Antônio's companions died of pneumonia in a crude shelter they had erected in a forest seventy-five miles southwest of Itatinga. The other had been caught at a senzala. Antônio had been waiting in trees on a hill behind the slave quarters of a fazenda thirty miles from São Paulo. He had heard a commotion as the fugitive was seized by those from whom he sought food. Without waiting to learn what happened, Antônio had run from the hill. He was the only one of the three to reach São Paulo, but he had been in the city only three days when he was arrested as a vagrant.

The senhor barão himself had stood on the far side of the senzala to witness the lashes given the young mulatto under the supervision of head overseer Eduardo, whom the slaves called "Setenta" (Seventy) for the number of lashes he most favored: "Neither too many nor too few" were Setenta's sentiments. "I should sell you to an other fazendeiro, Antônio Paciência," Ulisses Tavares had said, "but I'm not a man to pass on my mistakes to others. You came to me as a child and your bad ways were learned at Itatinga. However long it takes, here, too, we will teach you to be a good slave."

But Ulisses Tavares had changed his mind about keeping Patient Anthony. One morning in February 1865, Antônio and five others condemned as lazy or rebellious by the overseers had been lined up in front of the mansion to be told by the senhor barão that they were leaving Itatinga.

"You have not served me well," Ulisses Tavares had said. "You've earned more lashes than the rest of the slaves together. May Jesus Christ, who forgives all, help each one of you! Be loyal! Be trustworthy! Be proud of the service for which you are chosen! Above all, slaves - be brave!"

Ulisses Tavares was donating the six slaves to Emperor Dom Pedro's army. Though careful to select a group of malefactors whom he considered incorrigible, the senhor barão had made this gesture out of noblest patriotism. Many other slave owners picked out a few blacks or browns for the war against Paraguay, but only because these were accepted as substitutes in lieu of service by themselves or their sons. The senhor barão had a mighty contempt for cowards unwilling to fight for Brazil, and in this he was justified, for when the ninety-two voluntários of Tiberica had left the town square, his grandson had ridden at the head of the column.

Included in the column, marching three abreast, had been twenty-seven slaves from fazendas in the district. Some had tramped along with bewildered looks, for they feared this service for which their masters had volunteered them; some had stepped forward elatedly as the townsfolk cheered them. Antônio Paciência had been among the latter, and beside him marched Policarpo Mossambe, one of the six chosen from Itatinga as voluntários da patria.

As the sun rose on the Upper Paraná on the morning of April 10, 1866, Antônio and Policarpo had started down the hill toward their camp. They could hear the sounds of battle from the sandbank opposite the Paraguayan battery at Itapiru. Through the thin tree cover, to the left and right of them, were others who had climbed up for a view of the battle. As in the camp below, and wherever the Brazilian army was gathering for the invasion of Paraguay, the scene held a certain incongruity.

This was South America, but here were thousands of Africans massed for battle. The number of African slaves enlisted in Dom Pedro's army by April 1866 was no fewer than ten thousand; mulattoes and other mixed breeds swelled the number of slave soldiers to fifteen thousand. And as popular enthusiasm for the war waned with the dimming prospect of swift victory, another group of voluntários had had to be compelled to serve their emperor: In the sertão of Pernambuco, the Bahia, and other provinces, recruiters were rounding up the landless class, chaining them together and marching them down to the coast for shipment to the Plata.

This morning, shortly after Antônio and Policarpo reached the camp, the guns at Itapiru fell silent. Firmino Dantas was away at the headquarters of First Corps commander General Manuel Luís Osório, and his two camp attendants had the morning to themselves. They had gone to the riverbank above the assembly point of the invasion flotilla when the first news came of the fight on the sandbank.

"The Paraguayans are defeated!" a boatman had shouted. "The island is ours!"

"Viva! Viva! Viva! Viva Dom Pedro Segundo! Viva Brasil!" A tremendous cheer rose from the men on the bank.

Policarpo seized Patient Anthony in a fierce embrace. "At last, the battle can begin! We can cross the Paraná to drive the Paraguayans to Asunción! We can cross the river, Antônio Paciência, to freedom. Freedom!" Policarpo believed the circulating rumors that slaves who fought for the emperor in Paraguay were to be freed.

"It's only a rumor, Policarpo - the hope of all slaves," Antônio Paciência cautioned.

"Remember, Antônio, I have seen the emperor riding in his carriage at Rio de Janeiro. A great monarch! A wise man! When we defeat his enemies, he will say to us, 'From this day, you are free, my Brasileiros.'"

On April 15, 1866, ten thousand men of the Brazilian First Corps under Manuel Luís Osório boarded eleven steamers and canoes and floating piers towed by the ships. Another force of seven thousand Allies, mostly Argentinians, was assembled for embarkation immediately news came of a successful landing by the Brazilians. A Brazilian fleet of seventeen ships in three squadrons rode off the Paraguayan banks, along three points from Tres Bocas to a position fifteen miles away, close to the town of Paso la Patria, the headquarters of Marshal López.

The company of Tiberica volunteers were being transported on one of the three floating piers towed by the steamer carrying General Osório. By 7:00 A.M. on April 16, this vessel was heading directly toward a channel between Itapiru and the sandbank where the Brazilians had been victorious five days ago. "Isle of Redemption," the spit of land had been called, though there had been no deliverance for eight hundred men killed there.

Firmino Dantas da Silva was aboard the steamer with Osório and his staff. He stood at the starboard bulwarks with other officers of the voluntários, feeling an intense nervous excitement as explosions from shells fired by the heavy guns of the naval escort tore up the riverbank, knocking trees to splinters and setting the forest ablaze. The Itapiru battery responded with a continuous grumble, the water rising like a geyser when the Paraguayan shot burst in the river.

Firmino had waited fourteen months for this moment, months during which he'd thought often of returning to Itatinga. At the garrison of Bagé, where the company had been trained, Firmino had not impressed the regular army officers, with whom he had little in common. "O Pensador" ("The Thinker"), his fellow officers had nicknamed him.

At last, the company had been sent to the northwest of Rio Grande do Sul, and Firmino had discovered an unoccupied ranch beside a tributary of the Rio Uruguay where they could camp during the bitterly cold, wet winter. Daily patrols scoured the riverbank, as much to look for Paraguayans as to forage for food. Slave soldiers like Antônio Paciência and Policarpo were set to planting corn, manioc, and other crops. Firmino dispatched regular reports to the Bagé garrison, but, though he received routine acknowledgments, it seemed that the Tiberica company had been forgotten.

Some of the voluntários resented the inactivity and blamed Firmino Dantas, who could have appealed to Bagé to have the company transferred but seemed perfectly content to stay at the old ranch house reading books he had brought with him. O Pensador, thinking, dreaming, waiting for the war to come to him! Inevitably, others had another explanation for Firmino's apparent willingness to sit out the war far from the battlefront: "The barão de Itatinga's grandson is frightened."

Finally ordered south, the company headed for the camp near the port of Corrientes; there Firmino Dantas found his cousin, the artillery captain Clóvis da Silva, at Lagoa Brava. Clóvis, who had already fought against the Paraguayans in Corrientes province, was also critical of Firmino Dantas's inaction since leaving Tiberica.

"The barão didn't encourage you to volunteer for so miserable a post," Clóvis da Silva said that first night as they dined together at the Hotel Riachuelo, one of many establishments flourishing at Corrientes with the influx of thousands of troops and camp followers.

"I'm not a professional soldier, Clóvis."

"Good God, man, that's not the issue. As the grandson of the barão de Itatinga, you can do better than sit in camp for eight months. Ulisses Tavares expects more than this, Firmino Dantas."

After that meeting, Clóvis da Silva had arranged for Firmino to be made liaison officer with Osório's headquarters. The promotion had brought him into contact with the command of the First Corps and offered good prospects for rapid advancement. Still Firmino Dantas had been a reluctant participant, carrying out his orders efficiently but without the show of spirit to win the attention of his superiors.

Firmino dearly longed to be back at Itatinga, where he could continue his experiments with the coffee mill. Where he could see the girl about whom he had dreamed all these months! Since the night of the baronesa's ball, Firmino's passion for the golden-haired Renata had grown. Before marching away, he had gone to August Laubner's shop in Tiberica and asked the apothecary to put together a personal medical kit for his campaign. There he had seen Renata Laubner. Firmino had gazed into those brilliant blue eyes as she talked with him, and had openly revealed his admiration - his adoration! The moment August Laubner went to the back of the shop in search of something, Firmino had suddenly taken hold of Renata's hand and pressed it to his lips.

His commitment to Carlinda troubled him. He knew also that his betrothed's fiery-tempered ally, Teodora Rita, would oppose any breach of promise. But, as the months passed, Firmino had built up hopes of a relationship with the Swiss beauty that went far beyond what could be justified by one touch of his lips to her hand. "Oh, my love, Renata," Firmino would whisper to himself "I'll fight this war and return to Tiberica, where you await me."

Now, as Firmino stood on the deck of the steamer leading the invasion flotilla toward Itapiru, the thunder of war bursting around him, with an ironclad off to starboard, her flame-belching Whitworths unleashing destruction against the enemy, his nervous anticipation gave way to elation.

Firmino glanced toward General Osório, who was fifty-eight years old, gray-haired, with alert, genial eyes, a bona fide officer and gentleman. Osório had been nineteen when he fought in his first battle in the Banda Oriental in 1827, and had gained a legendary reputation as a lancer.

When Firmino first met the general at his headquarters, where he had gone as battalion liaison officer, Osório had remarked that the name of Ulisses Tavares da Silva ranked high among those who had made King João's conquest of the Banda Oriental in 1817. "Show half the spirit of the barão on that campaign, Firmino Dantas, and you'll make the old Paulista a proud man." Firmino Dantas had promised to do his best. Alone, he had felt his deep dread of failure in battle against the Guarani, whom Ulisses Tavares, like His Majesty Dom Pedro, considered a worthless enemy.

But Firmino's apprehension vanished as the invading force rode forward. The Paraguayan gunners were finding their mark now, and scored hits on a nearby ship and a floating pier. But as the range closed, with the steamers still several hundred yards off the Isle of Redemption, the lead ships of the flotilla began to turn to port. One after the other, with the floating piers in tow and the canoes keeping in the lee of the transports, the ships began to move down the Upper Paraná toward Tres Bocas: The landing had been planned not at Itapiru but at a point about half a mile beyond Tres Bocas on the Rio Paraguay itself.

"Macacos . . . macacos . . . macacos."

General Juan Bautista Noguera intoned the epithet with a deadly calm as he watched the river armada draw near the low-lying banks where the Rio Paraguay fell into the Paraná.

Four thousand soldiers were in position along the banks of the Upper Paraná, the majority between Itapiru and Paso la Patria. An invasion by the Allies had been accepted as inevitable for months, and the Paraguayan High Command had seen little hope of effectively resisting a landing by the enemy's overwhelming numbers. Cacambo had been among the few to protest this; he agreed with Marshal López's English engineers, Colonel George Thompson and Lieutenant Hadley Tuttle, who had argued that Paso la Patria, Itapiru, and other possible landing places should be defended with every gun that could be brought down from Humaitá garrison.

Marshal López had rejected this plan. He accepted the fortification of Humaitá as Paraguay's key defense. The riverside batteries provided tremendous firepower, and almost a year after the victory at Riachuelo; the Brazilian fleet had not yet dared make passage toward Humaitá. But more than the guns of Humaitá awaited an enemy: There were the esteros, a natural defense every bit as daunting as the man-made works at Humaitá. The "Place of the Damned," Marshal López called it.

Behind the carrizal, situated between two parallel streams - Bellaco Norte, just below one line of outworks of Humaitá, and Bellaco Sur, about three miles to the south toward the Upper Paraná - lay the esteros. A dense forest of Yatai palms grew on heights thirty to eighty feet above the swamps, which were clogged with rushes and three to six feet deep. For an invading force, few fields of operation could be worse than that toward which the Allied troops were heading this morning of April 16, 1866.

Just past 8:30 A.M., Cacambo and his company were in a palm grove two hundred yards from the Rio Paraguay. Behind them was an extensive morass; in front of them, a narrow strip of open, firm ground, which for the past twenty minutes had been plowed up in a continuous bombardment by the enemy.

"Macacos . . . macacos . . . macacos."

War steamers, transports, flat barges, and canoes as far as the eye could see. And to challenge them, Cacambo with two hundred men and boys, most of them carrying flintlock muskets and machetes. Cacambo had sent three men to a Paraguayan detachment two miles to the east, behind the morass and below Itapiru, but he knew it would take his messengers at least an hour to get through the marshes.

The palm grove stood on low-lying ground and provided the scantiest cover for Cacambo's force. Men had thrown up small earthworks where they sheltered, but the Brazilian barrage was relentless and deadly. In fifteen minutes, Cacambo's company lost fifty men, and in the fire- storm between the palms, many more were deafened by the blasts. Only a few stood firm as the majority backed off into the morass.

Cacambo saw how bad it was. He did not curse those who fled. The company flag bearer, a boy of eleven, stood near him. Cacambo stared at the red, white, and blue banner of the Republic of Paraguay. "Go!" he said. "Carry our flag to safety."

The boy was a Guarani from Cacambo's town. He shook his head.

"Go! Go!" Cacambo said. "You can do nothing here. Take our colors to Marshal López. Tell him, Cacambo -" A shell whistled into the palm grove, exploding close by. "Go!" he shouted. The young Guarani ran for the morass.

The Brazilian guns stopped firing. In the palm grove, trees cracked and thudded to earth; wounded men cried out; and on the ground beyond, where dust and smoke drifted, silence. But the stillness was soon broken by voices as three floating piers and two canoes of the enemy approached the bank of the Rio Paraguay.

With six men remaining, General Juan Bautista Noguera stormed toward the invaders. His comrades ran ahead of him, for he had not much wind left, this old Guarani who long ago should have taken his rest with those elders who lay in their hammocks. He stumbled a few times, almost losing his footing as he skirted the craters from the enemy cannonade. He had unsheathed his sword and was wielding it with both hands.

The men in the floating piers saw the six front-runners bunched close together, their red blouses offering easy targets. Fusillades from two crowded piers stopped the six Paraguayans in their tracks.

"Macacos . . . macacos . . . macacos."

Cacambo ran on. His gaze was on the lead canoe. He saw a great macaco there, standing insolently in the prow, wearing a white kepi and blue poncho and carrying a silver-plated lance.

Cacambo was twenty yards from the edge of the riverbank when four Minit balls struck him. General Juan Bautista Noguera stumbled forward a few feet and then fell.

"My Guarani . . ." he wept, with his last breath.

The man in the white kepi was the first Brazilian to set foot on Paraguayan soil: General Manuel Luís Osório, who would be honored for this triumphant moment with the title Barão de Herval.

Thirty-eight days after the landings near Tres Bocas, the exhilaration Firmino had experienced during the invasion was gone.

On the push through the carrizal east from the low banks at Tres Bocas toward Paso la Patria, Brazilian troops had skirmished with Paraguayans deployed around the lagoons and morasses. The Tiberica contingent had reached Paso la Patria on April 21 without firing a shot other than rounds spent by nervous voluntários blazing away at noises in the jungle.

Firmino began to pay the price for the months in which he had kept to himself: utter loneliness, no fellowship at all with other officers or the men of his company. Even with Clóvis da Silva, whom he saw often at Paso la Patria - now a sprawling base for the Allied bridgehead - Firmino found it difficult to make conversation. The artilleryman's confidence left Firmino feeling totally inadequate. He recognized the major - Clóvis had been promoted since the landings - as exactly the kind of soldier Ulisses Tavares expected Firmino to be.

To make matters worse, listening to Clóvis and the others, with their boisterous, passionate, jocular talk of combat, only intensified Firmino's feeling of isolation. He looked at dead Paraguayans beside the route of march and imagined himself a corpse; he spoke with survivors of the May 2 attack on the vanguard, which had lost sixteen hundred men, and was certain he would run from such an onslaught. These anxieties grew until he could contemplate little else, not even the command of Ulisses Tavares, who had sent him south to uphold the heroic name of the da Silvas of Itatinga.

On May 24, 1866, thirty-eight days after the landings, the Allies' forward positions were along a three-mile front at Tuyuti, an area of higher ground with palm forests just north of the stream of Bellaco Sur and on the southern fringes of the swamps and morasses. Thirty-five thousand men had moved up here from Paso la Patria, with more than one hundred field guns. The Brazilian divisions held the left flank, the Argentinians the right. There were nine hundred Uruguayans, all that remained of the battalions led by the Colorado general Venancio Flores. The Allies were still under the overall command of the Argentinian president, General Bartolomé Mitre, and General Osório led the Brazilian army.

On May 24 at Tuyuti, General Mitre ordered a reconnaissance in force into the esteros. Firmino Dantas and the Tiberica company were with a division near the rear of the Brazilian left flank. General Antônio Sampião, a veteran infantryman from the northeast province of Ceará, commanded these battalions of Paulista, Carioca, and Cearense voluntários holding positions in support of an artillery regiment - the Bateria Mallet - with twenty-eight Whitworth and La Hitte cannons. Major Clóvis da Silva served with these batteries, which were led by and bore the name of the French-born Emilio Mallet, who had come to Brazil as a mercenary in the 1820s and had risen to be the best gunner in the imperial army.

Late morning, along the Allied lines, the battalions chosen to reconnoiter the esteros were awaiting orders to penetrate the marshes. The atmosphere was hot and humid, the sky cloudless, and as the reconnaissance forces were mustered, sweat-drenched men cursed impatiently; they didn't expect the probe into the esteros to amount to much.

Firmino Dantas and his men were with other voluntários three hundred yards to the left of the Bateria Mallet. The company's position was on an elevation covered with Yatai palms. Below the slight slope, the ground leveled out toward an open morass extending from the reed-clogged esteros. A wide, deep ditch had been dug in front of the twenty-eight field guns, and the earth that had been removed from this trench spread out in front of and behind it so that from the edge of the esteros the long pitfall would not be visible.

At precisely 11:55 A.M., a Congreve rocket tore into the air and burst above a patch of jungle to the left of the Brazilian positions. Here and there a bugle sounded, a whistle shrilled, as officers quickest to react brought their men to orders.

A few minutes after the rocket explosion, a Brazilian skirmisher came running out of the jungle:

"Camarada! Camarada! Os Paraguaios! Os Paraguaios!"

From the jungle on the left came eight thousand infantry and one thousand cavalrymen, who had had to dismount and lead their horses in single file through the dense undergrowth. Sweeping down on the right toward the Argentinian flank, thundering out of the cover of a palm forest, came seven thousand cavalrymen with two thousand foot soldiers running up behind them. Pouring directly from the estero in a frontal assault on the Bateria Mallet were five thousand infantrymen, with four howitzers. Altogether some 23,000 men, the bulk of Paraguay's army.

By noon of May 24, 1866, five minutes after the Paraguayans' rocket signal to commence the attack, the battle of Tuyuti raging along the whole line of the Allies.