Excerpted from Brazil, a novel by Errol Lincoln Uys

"Descriptions like those of the war with Paraguay, particularly the battle of Tuiuti, do not find in our literature any rival capable of surpassing them and evoke the great passages of War and Peace rather than best-sellers of current extraction. " -- Wilson Martins, Jornal do Brasil

NOVEMBER 1864 - JUNE 1865

On the first Saturday in February 1865, colored lanterns illuminated the gardens of the Fazenda de Itatinga and the moon silvered the Rio Tietê beyond. From within the mansion came the music of quadrille, waltz, and polka danced by the guests of the baron and baroness of Itatinga.

The seventy-five-year-old Ulisses Tavares da Silva, immaculate in black tailcoat and trousers with white waistcoat, shirt, cravat, and collar, moved through the figures of a quadrille with a lively step and with a twinkle in his eye for the baronesa. Teodora Rita had lost her youthful plumpness. Her slender waistline was pulled in tight above an immense oval-shaped skirt, with her corset rising high under her breasts and lifting them slightly.

The baronesa confounded those who had scoffed at Ulisses Tavares's infatuation with a twelve-year-old, for, growing to womanhood at his side, she had become a faithful, loving wife. And a mother, too; the barão had known a virile renewal with Teodora Rita, and they had been blessed with a son five years ago and a daughter the next year.

When the quadrille ended and Ulisses Tavares bowed gracefully to Teodora Rita, spontaneous applause for the couple filled the ballroom, on this night of a grand ball, to which 140 couples had been invited to celebrate Teodora Rita's twenty-second birthday.

Few celebrations at Itatinga had been as carefully planned as this party for Teodora Rita or so clearly marked the shift of prosperity from the engenhos of the north to the fazendas of the southern coffee growers. At Itatinga, the barão could ride for hours between endless rows of half a million coffee trees, their fragrance as strong and heady as the prospect of the fortune to be collected from branches heavy with small reddish-brown berries.

Ulisses Tavares had seven surviving children from his previous marriage, two of whom lived at Itatinga with their families: a daughter, Adélia, and Eusébio Magalhães, father of Firmino Dantas. (The baron's firstborn son, Silvestre, named for Ulisses Tavares's own father, had drowned when the ship carrying him from Lisbon after five years' study and travel in Europe was lost near the Azores.) Eusébio Magalhães, the second-born son, already in his fiftieth year, was a silent, tense man with pale eyes. He had a prodigious memory and a tendency toward obsequiousness in the presence of Ulisses Tavares. "The Bookkeeper," the baron called this son, intending praise, for Eusébio Magalhães was a wizard with figures and an excellent administrator of Itatinga.

Eusébio Magalhães and his wife, Feliciana, a matronly, mild-mannered woman, had taken a long time to adjust to Teodora Rita, whose early impudence toward Dona Feliciana had moved Ulisses Tavares himself to admonish his child bride to show consideration for his daughter-in-law. But now, as she watched the baron and his young wife pick up again and glide gracefully past her, Dona Feliciana gave them a broad smile, for perplexed as she had been and still was by her father-in-law's romance, she did not begrudge Teodora Rita admiration for the happiness the girl had brought the old man.

Ulisses Tavares and Teodora Rita had been at the top of the line of couples for the quadrille; Firmino Dantas and his partner had been at the bottom. Twenty-five years old, Firmino Dantas da Silva held a law degree from the school at São Paulo and a baccalaureate from the University of Paris. He was scholarly and serious but not pedantic, and his gray-green eyes sometimes held a restless, dreamy look. Of medium build and slender, Firmino Dantas had long, dark lashes, a straight, perfectly shaped nose, sensual lips, and a dimpled chin, which he kept shaved. The eyes of many young ladies drifted toward Firmino Dantas this night, but he was beyond reach of all save one, to whom he had been betrothed this past December.

Firmino Dantas's fiancee was nineteen, a lively, lovable girl, petite and dark-haired, with a strong face and a determined look that said something of her ambition to be Firmino's wife, a cause in which she was now certain of triumph. But then, Carlinda da Cunha Mendes had had powerful support in winning the affections of Dantas da Silva: She was the sister of Teodora Rita.

Carlinda had been a regular visitor to Itatinga before Firmino Dantas left for Paris; but, upon his return eleven months ago, the baronesa energetically set about promoting a match between them, with the support of Ulisses Tavares, whose encouragement often had the ring of command behind it. As a suitor, Firmino Dantas was absentminded and reticent. With Carlinda Mendes, he had been kept on track by the baronesa and Ulisses Tavares, who continued to coax him toward this promising and sensible union. Not that he needed coaxing; he had a genuine affection for Carlinda - and she an intense passion for him.

These past eleven months, Firmino Dantas had spent most of his time at Itatinga, and appeared reluctant to follow the practice of law, for which he had studied so long and diligently. His father, Eusébio Magalhães, had spoken with him about this, urged on by an impatient Ulisses Tavares eager for his grandson to begin a career that offered so much to the bright young men of the empire. Dom Pedro Segundo esteemed cap and gown and frock coat, and regarded the senhores académicos as the new pioneers who would spread law and justice through his backward and rustic realm.

"You will be leaving for São Paulo soon?" Eusébio Magalhães had suggested to Firmino one day the previous June.

"I've thought about it, Pai."

"Good." Eusébio Magalhães had looked at his son expectantly. Father and son were not close. Eusébio Magalhães and Dona Feliciana had three daughters, all married. Firmino was their only son. But they had lost him, in a way, even when he was still a boy, for he had been the favorite grandchild of Ulisses Tavares, who had involved himself in every aspect of Firmino Dantas's upbringing. The barão had never said as much, but the attention he gave this grandson was not unrelated to the loss of his own firstborn, Silvestre, for whom he had entertained high hopes.

"The barão himself is anxious to see you established."

"I understand, Pai. I won't disappoint Grandfather."

"Of course - Doutor Firmino Dantas." Lawyer, medical doctor, scientist, intellectual - all sons of the empire who had graduated from university earned the respectful address of "Doctor."

Suddenly, Firmino had said, "Pai! Please, come outside!"

The harvesting of mature coffee trees had begun in May, the first of the cool, dry months. From dawn until dark, 220 adult slaves and 190 agregados - tenants, sanctioned squatters, sharecroppers - worked at stripping the branches of 400,000 trees, the harvest of coffee beans expected to reach six hundred tons.

Firmino Dantas had taken his father toward the fazenda's smithy and work shops, past the terreiro, an acre-sized terrace of slate where picked berries were spread out to dry in the sun. When the skins of the fleshy berries were shriveled, hard, almost black, they were ready for processing in a water-driven mill near the terreiro.

Firmino Dantas had stopped at the mill. "Maravilhoso!" he had shouted sardonically above the stamp of four huge metal-shod pestles. "We live in the age of steam and invention, and here - a medieval monstrosity!"

They had watched as slave women expertly tossed the pounded berries on screens to separate them from the broken outer covering. The two beans in each berry were still sealed in a double membrane: The pounding process had to be repeated, with hand-driven ventiladores blowing away the chaff, and the blasts of fine dust swirling around the coughing, spitting workers.

"Six hundred tons to be fed to this monster!" Firmino Dantas had exclaimed, throwing up his hands. "Father! There has to be a better way!" And he had moved off, beckoning Eusébio Magalhães to follow him as he crossed to the fazenda's workshops.

Eusébio Magalhães and Ulisses Tavares had become aware, from Firmino Dantas's letters from Paris, that the philosophical studies intended to broaden the young lawyer's horizons had taken second place to a fascination with science and technology. They had not expected, however, that upon his return to Itatinga, after a month of brooding over the "monster" the barão regarded as one of the finest mills for a hundred miles, Firmino Dantas would suddenly be seized with the idea of building a machine to shell and clean the harvest. Ulisses Tavares had initially been indulgent, and had even encouraged the scheme by approving the purchase of a small steam engine from Rio de Janeiro, believing that Doutor Firmino Dantas's flirtation with the role of mechanic would pass quickly and was but a healthy diversion after eight long years of study.

But Firmino Dantas had remained dedicated to "The Invention," as the family called it. Repeatedly the contraption had rattled and shaken itself apart, and it lay dismantled in a sad heap, like a cast-off suit of armor. Firmino Dantas had reassembled it patiently, piece by piece, and though his invention continued to break down and spew coffee beans in every direction, he had shown no sign of abandoning the project.

The senhor barão had become impatient and not a little vexed to see his grandson laboring beside tradesmen. On this night of the ball, several times already, Ulisses Tavares had steered his grandson into the company of a district judge and a lawyer - the latter, the present incumbent of the seat Ulisses Tavares had held in the provincial assembly - in the hope that contact with these homems bons would remind Firmino Dantas of the high calling for which he had been trained.

The quadrille had been followed by a long interval during which several couples hovered impatiently beside the dance floor before the orchestra signaled they were ready to play a waltz. Three skilled musicians had been engaged from São Paulo and nine local bandsmen belonging to the Guarda Nacional of Tiberica; four Itatinga slaves, three who played fiddles, one a flute, joined them. This disparate group had been brought into harmony in only two days of practice led by M. Armand Beauchamp, master of music and dance.

Seated at an English grand piano, Professor Beauchamp played a few opening bars to alert the dancers and then paused for some moments, casting a sidelong glance at the couples and smoothing down his thick black mustache. M. Armand took pains with the upkeep of his mustache; he believed that a good mustache improved the tone of the voice, acting as a resonator and helping to conceal any distortion of the mouth in singing.

Firmino Dantas and Carlinda were first on the floor for the waltz, followed by Teodora Rita on the arm of a lieutenant of the Guarda Nacional. Ulisses Tavares stood with a smile at the sight of his bride swept along by the young officer. But after a while the barão said wistfully to a man next to him, "Oh, Clóvis, God grant that I were ten years younger this night."

Clóvis Lima da Silva was the third son of the Tiberica merchant José Inocêncio da Silva and the grandson of André Vaz, who had perished in exile in Africa. Together, Clóvis's dark eyes and slightly coppery skin hinted at his native ancestry: Through the family of André Vaz, the thirty-six-year-old Clóvis was descended from Trajano, the bastard son whom Amador Flôres da Silva had executed on his seven-year odyssey in search of emeralds. At nineteen, Clóvis had gone to the Escola Militar at Rio de Janeiro, where he had trained as an artilleryman. He had served with the army ever since and now held the rank of captain.

Clóvis da Silva knew that Ulisses Tavares's remark had nothing to do with envy of Teodora Rita's dancing partner. "Senhor Barão, in your day few served their king with as much valor," he said.

"I did my duty, Clóvis."

"Much more, Senhor Ulisses. Much more. The barão's deeds are remembered."

"Today, Clóvis . . . if only I could ride with the army today! To triumph, as in King João's day, in lands that were ours until Pedro I surrendered them." His voice rose sharply: "How many times, Clóvis, must the cost of that defeat be borne by Brazil - and paid for with the blood of our nation's sons?"

Ulisses Tavares's anguished appeal caused several heads to turn in their direction and seemed out of place in that romantic setting. But half the men waltzing their sweethearts round the ballroom were in the dress uniforms of the imperial army and Guarda Nacional, for amid the music and laughter, there was talk of war - three conflicts, in fact: one drawing to a close, one of uncertain outcome, and one that had begun four months ago and to which the barão de Itatinga but for his age would have marched posthaste.

Reports from North America suggested the imminent collapse of the Confederacy. Brazil had maintained an official policy of neutrality throughout the Civil War, though her recognition of the South's belligerent position had been the cause of acrimonious exchanges between Dom Pedro's officials and envoys of the Lincoln government at Rio de Janeiro, especially when raiders like the Alabama and the Florida put in for provisions in Brazilian ports.

The second conflict exciting interest among the guests at Itatinga this night was in Mexico, where more than 35,000 soldiers of Napoleon III had secured the Crown for Ferdinand Maximilian, brother of Franz Josef of Austria.

The third conflict involved Brazil on two far-flung fronts. After firing her shot across the bow of the Marquês de Olinda, the Paraguayan steamer Tacuari had escorted the Brazilian packet back to Asunción, where her cargo of munitions and strongboxes were seized and all Brazilians aboard, including Mato Grosso's president-designate, Carneiro de Campos, interned. Rio de Janeiro's minister at Asunción, Viana de Lima, had been handed his passports and ordered out of Paraguay. When news of these events reached Rio de Janeiro in late November 1864, war fervor had quickly spread.

The bulk of Brazil's sixteen-thousand-man army was already engaged in Uruguay, fighting in support of the Colorado faction against the Blancos in power at Montevideo. The Guarda Nacional was prohibited from foreign service, a law for which numerous colonels and their local militia showed a sudden respect: It was one thing to parade around the local square and maintain the peace of the colonel's district; quite another to go up against the Guarani horde of Paraguay. To meet this contingency, the imperial government had issued a decree for volunteers for battalions of 830 men between the ages of eighteen and fifty.

Response to the call for voluntários da patria was brisk, for the decree had immediately followed reports of a Brazilian victory in Uruguay. On January 2, 1865, after a month's blockade and a fifty-two-hour bombardment by ships of the imperial navy, the Blanco port of Paysandu on the Rio Uruguay, one of the Blancos' last strongholds outside Montevideo, had surrendered to the Brazilians and Colorados. But there was much more than this to spur the Brazilians to act against their newer foe, Paraguay.

"Thousands of Paraguayans defiling Brazilian soil! Our brave defenders slaughtered!" Ulisses Tavares said to Clóvis. "Men, women, and children driven into captivity. Others cast into the sertão upon the mercy of savages. Oh, dear God, Clóvis: Mato Grosso invaded by López!"

On December 27, 1864, a Paraguayan naval squadron with three thousand troops and a land force of 2,500 cavalry and infantry had attacked Fort Coimbra, southernmost defense works of Mato Grosso, which had surrendered after a thirty-six-hour resistance.

The barão and Captain Clóvis da Silva left the dance floor and went outside, walking slowly across the paving between the two ells.

"What terrors they must be enduring there," Ulisses Tavares said, looking up at the sky. "Beneath these stars."

"López struck where we're weakest, Senhor Ulisses. He - "

"Rejoices!" Ulisses Tavares interrupted. "López pirates our Marquês de Olinda. He violates a frontier where the forts are few and falling to pieces. These are his victories over Brazil, this despot who dreams of being emperor and stirs his Guarani regiments with talk of glory."

"The Paraguayan will realize his mistake," Clóvis said, breaking his silence, "but it may take longer than we think to bring him to his senses."

"López?"

"The Guarani soldier, Senhor Ulisses. He's been taught absolute obedience to his dictator."

"They will be matched, Clóvis, man for man, by the voluntários."

Ulisses Tavares was too old for the battlefields of Paraguay, but he was doing all within his power to recruit a company of volunteers to be sent from Tiberica. As he walked with Clóvis da Silva, holding his arm again, he steered him toward an open doorway, through which they saw Firmino Dantas and Carlinda waltzing across the ballroom.

"In two weeks, Lieutenant Firmino Dantas and the voluntários of Tiberica leave for the Plata," Ulisses Tavares said. "Three months, Clóvis, and I believe they'll march into Asunción."

Firmino smiled at Carlinda, but his thoughts were far away. He had no argument with Brazil's cause, especially since the invasion of Mato Grosso, though he recognized López as provocateur and felt no particular hatred toward the Paraguayan people. And he was not without experience of the parade ground, having served with Tiberica's Guarda Nacional. But the prospect of combat sickened him.

The day word of the decree calling for voluntários da patria reached Itatinga, Ulisses Tavares had come to the fazenda's workshop in search of Firmino, whom he found standing on a platform at the second level of bins and ventilators of the coffee engenho. When Firmino waved a greeting to his grandfather, a slave misinterpreted the signal and flung open a valve to power the engine. With a tremendous clatter and grinding, the engenho came alive, making the barão jump back in fright. Shouting for the mill to be shut off, Firmino quickly scrambled down the platform.

One glance at the expression on the baron's face told Firmino that the old man's patience was exhausted, and he understood why: He had only to look at his own hands, ingrained with dirt, his knuckles grazed, his fingers cut and scratched. Ulisses Tavares's generation (and not a few senhores acadêmicos, too) was blinded by love of the past and faithful to ideas compatible with those of the lord donatários who had come to Terra de Santa Cruz in the sixteenth century: Progress was the extent of lands they owned; honor was the degree of royal approval they earned; dignity was the scorn of all useful labor.

Firmino lamented Brazil's backwardness compared with what he had seen in Europe. During those three years, 1860-1863, Firmino had found Paris being rebuilt to the grand designs of Emperor Napoleon III and his master planner, Georges Haussmann. "The broad boulevards, underground sewers, parks - gigantic works giving the city a new face! Glorious open vistas of air and light! Paris is in the midst of a revolution as dramatic a break with the past as the upheaval of 1789!" Firmino had enthused back at Itatinga.

He had also crossed the Channel to England, where he had marveled at the 22,000-ton Great Eastern: At Liverpool, he had roamed through the cavernous ship and stood in silent awe before engines capable of eleven thousand horsepower. How could he not consider positively medieval four iron-shod pestles serving to process six hundred tons of coffee beans!

He wondered if his grandfather would ever understand. But that day in the workshop, Ulisses Tavares had said nothing about Firmino's invention.

"Grandfather? There's something you wish me to do?" he had asked as he followed the old man outside.

"Yes, Firmino," Ulisses Tavares had replied gravely. "Francisco Solano López must be taught respect for the empire. A decree from the Corte asks for volunteers to crush the tyrant and his Guarani rabble." And then Ulisses Tavares had seized Firmino's hands: "My son" - his voice broke - "may God grant a swift, bold campaign." His grip on Firmino's hands tightened. "You will lead the voluntários of Tiberica, Firmino Dantas!"

Firmino knew that he would obey Ulisses Tavares, though he wanted nothing more than to continue the work on the coffee engenho. Three years away from Itatinga should have strengthened his independence, but back at the fazenda, he was one of several hundred people, slave and free, over whom the barão exercised absolute control.

In the ballroom at Itatinga, as Firmino danced past the barão and Captain Clóvis da Silva, his smile belied the deep concern he felt over his impending departure for Paraguay. Firmino had not shared his fears with Carlinda - perhaps because it was his mind and not his heart that guided him in accepting his coming marriage with this charming girl. This lack of ardor on her fiancee's part was not something Carlinda hadn't noticed. In fact, she had expressed some concern to her sister.

"My dear, be prudent and patient," Teodora Rita had counseled when Carlinda expressed dismay at Firmino's preoccupation with his invention. "The poor thing doesn't know love. An inventor. Be especially careful, Carlinda. Say not a word against his obsession with this machine. Your love is a prisoner in another shrine - the temple of learning. Show understanding. Keep him in good humor. He will bless the day he chose you!"

Restrained and chaste at the age of twenty-five, Firmino had not given those coaxing him into Carlinda's arms the slightest cause for doubting the success of their mission. Not until this night of the grand ball.

As midnight approached, Firmino remained on the dance floor under close scrutiny from his family, and especially Teodora Rita. Her pretty face was placid, but her dark, fiery eyes followed Firmino Dantas and the partner with whom he was dancing. The elation evident on Firmino's face made the baronesa regret having invited this girl and her father, August Laubner.

Laubner was a Swiss, a big, quiet man with drooping whiskers in the English "Piccadilly Weeper" style. He and his family had emigrated to the province of São Paulo from Graubünden, the easternmost canton, nine years ago with a group of two hundred people desperate to escape the hard, cold winters and the harder bite of poverty in the lonely valley of the Prätigau.

August Laubner had been a foundling. An apothecary, Jeremias Laubner, had found the infant in his barn, or so he said; rumor had it that Laubner had agreed to care for the bastard of a member of a family of old nobility who lived beyond Davos. August had been raised by the Laubners, who had one child, Matthäus, five years older than August.

From his fourteenth year, August had worked in the apothecary's shop. The Laubners had treated him kindly, if not with the love they were able to give only their own flesh and blood. Ultimately, he married and had two children. Then, in the winter of 1854, tragedy struck. Jeremias Laubner froze to death in a snowdrift into which he'd been thrown by his horse while riding back to Klosters from neighboring Davos, and six weeks later, Jeremias's wife had died of pneumonia.

Matthäus and his wife, as mean-spirited as her husband and expecting her first child, had given notice to August, who occupied two rooms at the back of the house with his family, demanding that they leave. "Find your own place, August, and find it soon," Matthäus had said, "for my wife's time is near, and there isn't room enough for two families."

At the time Matthäus ordered August to leave the house, recruiting agents for a group of Paulista fazendeiros had been active in the Prätigau valley seeking indentured workers for the coffee plantations, a free-labor alternative prompted by the ending of the slave trade from Africa to Brazil in 1850. At his brother-in-law's house, August had attended a meeting addressed by one of these agents, who offered passage money, transport from Santos to the north of São Paulo province, a subsistence allowance for the first year.

That same night, August Laubner decided to seek a new life for himself and his family in Brazil. A few harvests and his family would be free of debt. As soon as he had the means, he would establish himself as an apothecary.

After the long voyage from Europe and the trek over the Serra do Mar, August had come to a crude wattle-and-daub hut, with holes for windows and a thatched roof. Such was the home offered his family and five others whose contracts had been assigned to Alfredo Pontes, a fazendeiro who could scarcely distinguish between his colonos, as the share-wage earners were known, and his sixty slaves.

The colonos discovered that if Senhor Pontes was dissatisfied with their work, he could cancel their contracts and demand immediate payment of all monies due him. Failure to reimburse him resulted in two years in jail with hard labor or the same period at public works.

Senhor Pontes was, of course, only striving to instill in his colonos those virtues of obedience and subservience that fazendeiros expected from their agregados, the associates they permitted to live on their land under varying conditions of tenure. But the Swiss did not understand. After the first harvest, they complained that the prices quoted by their fazendeiros were far below market value for coffee beans at Santos, and many went on strike.

This confrontation had led to an investigation by a Swiss commissioner from the consulate at Rio de Janeiro, and the grievances of the colonos had mostly been confirmed. The imperial government had also sought to mollify the colonos, for the Corte was eager to attract European settlers. Several thousand German colonists were established on Crown lands in Rio Grande do Sul and prospering; the São Paulo indentured labor experiment with Portuguese, Germans, and Swiss was a private venture. Though both sides had calmed down and relations had improved, the effect of the "uprising," as Senhor Pontes and others saw it, was disastrous for Brazil: When the complaints of the colonos became known in Europe, Prussia forbade the recruiting of further migrants, and the Swiss cantons discouraged their poor from leaving for Brazil.

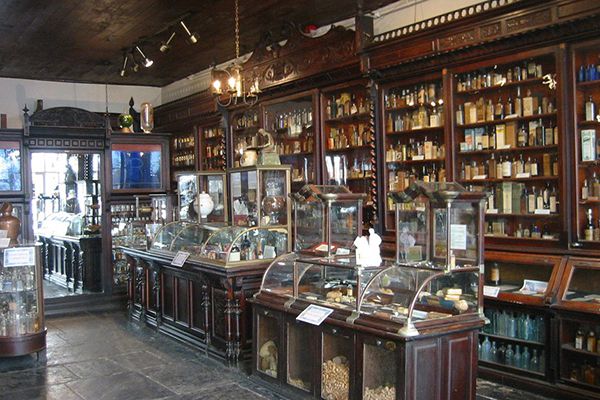

Senhor Alfredo Pontes had sold the contracts of the Laubner family and the others to another coffee grower, whose fazenda was twenty-four miles from Tiberica. This new employer, a Mineiro from Vila Rica, was scrupulously honest. Within three years, August and his family had paid off what they owed for their passage and subsistence allowance; at the beginning of 1862, August had been released from his contract and had come to Tiberica with his wife, Heloise, and two children, a boy and a girl, then aged eleven and fifteen. In March that year, in the front room of a small house, August Laubner had opened his apothecary shop, the first at Tiberica.

The barão de Itatinga himself was a customer of apothecary Laubner, and regularly used his dyspepsia powders for heartburn, and a tonic of beef extract, iron, and sherry as a flesh builder and blood purifier. Ulisses Tavares had heard only good reports about the Swiss and his family. Still, Ulisses Tavares had been disturbed when Teodora Rita told him that she had asked Senhor Laubner, his wife, and daughter to the ball.

"He will be uncomfortable among our friends," the barão had suggested. "They seek his professional help, yes. They value his advice, but they wouldn't want to see him in our ballroom."

"It's true, Senhor Barão," Teodora Rita had agreed. "Then, why did you invite him?"

"Forgive me, Barão, but there were several who asked."

"What, my girl?"

"The senhor barão, my love, has eyes only for Teodora Rita. He doesn't see that Tiberica's bachelors, young men of our best families, besiege the house of August Laubner."

"Ah, yes, indeed!" the barão said as it dawned on him. "Such a lovely girl!"

"Three hearts" - she had mentioned the names of three young men - "beating with one purpose: Oh, Senhor Barão, could I reject their lovelorn appeals that she be present at our ball?"

Renata Laubner was eighteen, a long-limbed girl with round blue eyes and a crown of blond hair parted in the center and pulled back to side ringlets, the golden tresses on the right adorned with small blue flowers. Renata's dress was a delicate blue, quite plain compared with the elaborate gowns of Teodora Rita and the others, but perfectly suited to her fair features. This girl who was so different from the sultry maidens of the tropics smote the bachelors of Tiberica who saw the flash of gold in her hair and the glorious blue of her eyes.

Firmino Dantas had met Renata Laubner for the first time this night. The apothecary had settled in Tiberica when Firmino was in Paris. After being introduced to August Laubner and Renata, Firmino had listened to the apothecary tell of a recent field trip to contact a group of semi-wild Tupi whose medicines August wanted to investigate.

"Truly, senhorita, you went with them into the sertão?" Firmino declared when August Laubner had finished his account.

"Why ever not, Senhor Firmino?" A smile, with a hint of impudence.

"Renata has a mind of her own, Doutor Firmino," Laubner said, looking fondly at his daughter.

"I wasn't afraid, Senhor Firmino," Renata said. "It was a wonderful journey.

Beyond the last fazenda, we spent three days on a trail through the forest. Every step was like walking through Eden. The flowers! The birds! A paradise, Senhor Firmino!"

Firmino had a feeling that this senhorita who so daringly walked beside her

father on his quest for knowledge would also understand his passion to launch Itatinga into the present.

But Firmino had shown characteristic restraint, pursuing serious topics of con versation for quite a while before asking permission for a dance. And then, when he'd taken Renata in his arms, he felt an exhilarating nervousness. He had had to wait almost an hour before he could politely approach her for a second dance, and had seen the three young men of Tiberica take turns throwing themselves at the feet of their idol.

When Firmino had been granted another dance, he was unable to hide his pleasure. He clasped Renata tightly round the waist as they glided swiftly along the floor.

When Firmino had escorted Renata back to her seat, Teodora Rita took her future brother-in-law aside. "The Swiss is lively," she said. "Such a fragile beauty blazing through the polka!"

Firmino at first did not sense the baronesa's concern. "Fragile, Teodora Rita?"

He laughed. "A girl who spent ten days in the sertão on a journey with her father?"

Teodora Rita looked shocked. "Whatever for?"

"Apothecary Laubner wanted to study the old remedies of the pagés. Senhorita

Renata went with him. Wasn't it marvelous?"

"It was silly," Teodora Rita said. "The girl belongs at home with her mother."

"Ah, but, Baronesa, Renata Laubner is different."

"Different?" Teodora Rita raised one eyebrow.

Firmino hesitated, becoming aware of the baronesa's irritation. But then he smiled. "Don't worry, Teodora Rita. Firmino Dantas hasn't lost his head in a Swiss cloud."

"I hope not, Firmino Dantas," the baronesa said, eyes blazing. She saw Ulisses Tavares coming toward them. "The barão, too." She nodded to herself. "He wouldn't like it, Firmino."

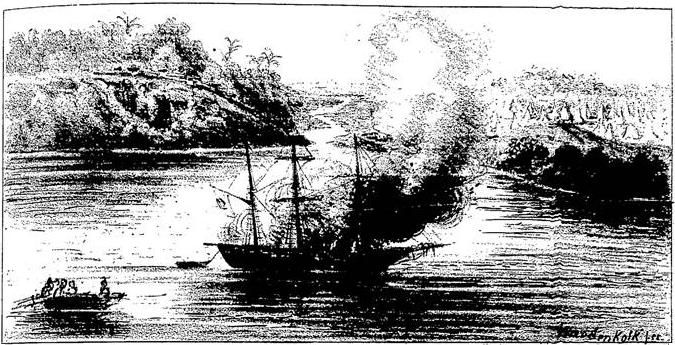

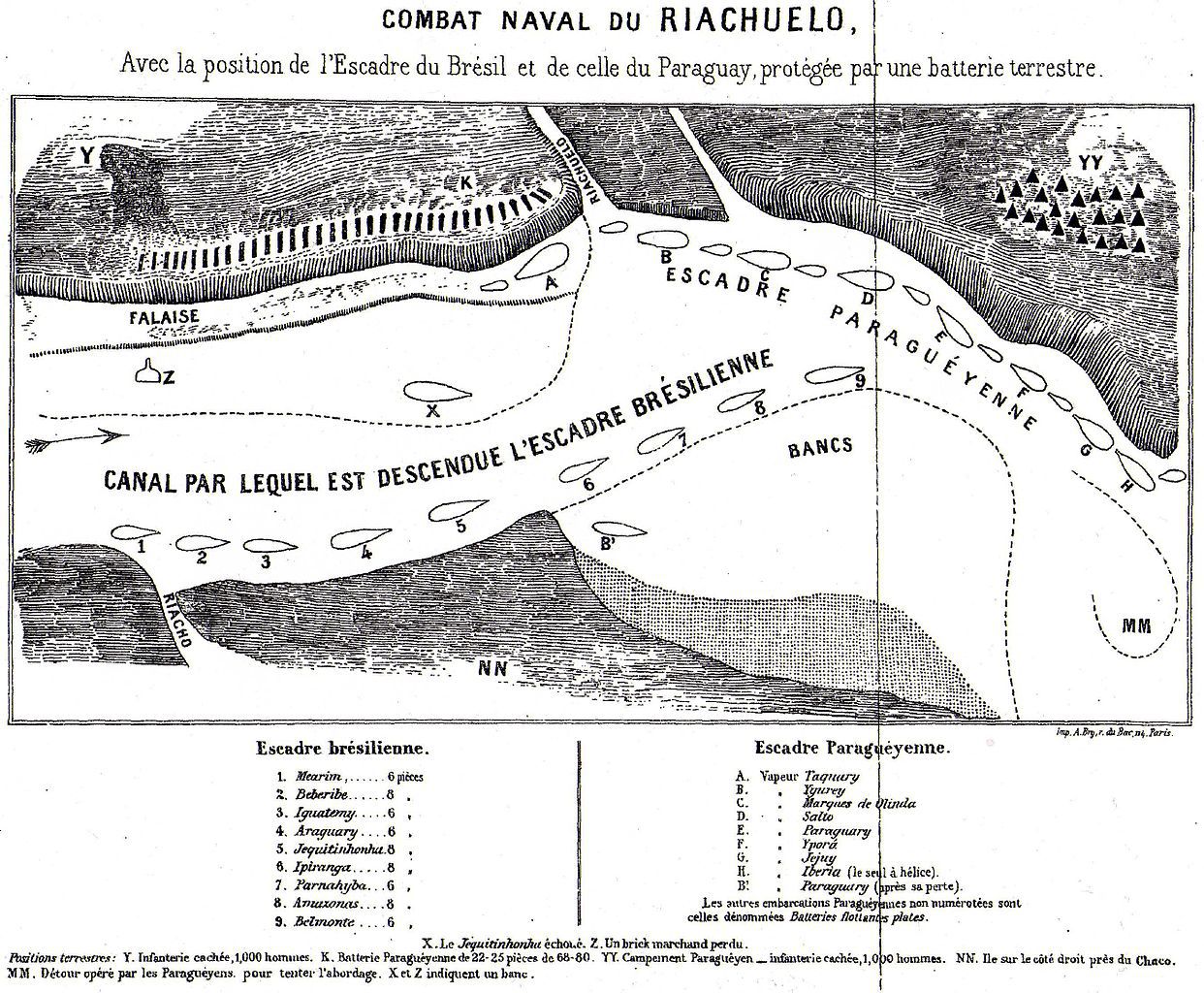

Early morning on June 11, 1865, nine Brazilian warships were anchored ten miles below Tres Bocas, the junction of the Paraná and Paraguay rivers, lying along a great bend of the Paraná - six hundred yards wide here - with the Riachuelo, a stream, flowing into it from the east. The squadron had a total firepower of fifty-nine guns, including Whitworth-rifled 120- and 150-pounders. The flagship was the Amazonas, a 195-foot, 370-ton wooden frigate, the only paddle wheeler among the nine ships. The others were screw-driven for greater maneuverability in the swift Paraná. Flying the blue naval ensign with stars at her mainmast, the green and gold flag of the empire at her mizzen, the black-hulled Amazonas carried a heavy ram at her bows, and strong and lofty nettings stretched above her bulwarks to protect against boarders.

This Sunday morning, the day of the Blessed Trinity, squadron commander Vice-Admiral Francisco Manoel Barroso, his officers, and 2,200 men, including 1,174 infantry of the Ninth Battalion, were turned out in dress uniform for sacred Mass, and their devotions were conducted with little concern for the enemy ashore. But, peaceful as the scene was, with the war steamers riding comfortably at anchor under a cloudless sky and the voices of men raised fervently with sacred song, on the east bank of the Paraná, just beyond range of their position, two thousand Paraguayans were encamped with a battery of twenty-two guns and Congreve rockets.

Clearly the optimism of men like the barão de Itatinga, who had predicted in February 1865 that Asunción would fall within three months, had not been justified. More than six months after the Tacuari lobbed her shot across the bows of the Marquês de Olinda, Brazilian soldiers had yet to set foot on Paraguayan soil. Worse, the war had widened: Argentina had joined in a triple alliance against Paraguay with Brazil and the victorious Colorado faction of Uruguay. This had come about after Francisco Solano López asked Buenos Aires to permit his army to cross Argentinian territory between the Upper Paraná and Uruguay rivers so that the Paraguayans could engage the Brazilians in Uruguay and drive eastward to Rio Grande do Sul. When Bartolomé Mitre, president of Argentina, refused this request, President López had gone ahead anyway, sending ten thousand men into the old Misiones district. In mid-March 1865, the Paraguayan congress had declared war against Argentina; on April 14, the Paraguayan navy had landed a force of three thousand men to capture Corrientes, a river port in the Argentine province of the same name. Corrientes had fallen without resistance, and within weeks, 25,000 Paraguayans had invaded the province with the objective of pressing south to Buenos Aires itself.

At the end of May 1865, the Brazilian squadron, under Vice-Admiral Barroso, had steamed up the Paraná carrying four thousand men to assault the Paraguayan occupiers of Corrientes. The attack had been successful, but after twenty-four hours, the Allies had reembarked their force, fearing a counterattack by units of 24,000 Paraguayans deployed within a few days' march of Corrientes. Since then, the Brazilian squadron had taken up position six miles from Corrientes in the river bend near the mouth of the Riachuelo to blockade the Paraná and prevent its navigation by the Paraguayan fleet.

By 9:00 A.M. on June 11, the two chaplains with the Brazilian ships had completed holy services. Less than a fortnight after the squadron had begun its blockade, the men already knew the monotony of a twenty-four-hour watch, day after day, with nothing to challenge but a few small riverboats and canoes, whose crews sometimes came upon the anchorage from backwaters where even the rumor of war was still unheard. Innocently, they would ride the swift current into the great bend, where first they encountered the lead ship Belmonte, then the flagship Amazonas , the corvettes Jequitinhonha and Beberibe, four gunboats - Parnaíba, Iguatemi, Mearim, and Ipiranga - and finally the rear guardship, the Aruguari, a gunboat with 32- and 68-pounders. Most impressive to the startled rivermen was the towering size of the black-hulled Amazonas , with her high paddle boxes and great ram, which lay menacingly in the channel between sandbanks and reed-clogged islands.

Aboard the Mearim this morning, the bell was rung for 9:00 A.M., the second hour of the forenoon watch. The Mearim was astern of the Belmonte but anchored so that her lookouts had a good view upriver. The notes of the Mearim's bell had no sooner died than there was a call from aloft: "Ship ahead!" And very soon, as a second and third vessel were seen: "Enemy squadron in sight!"

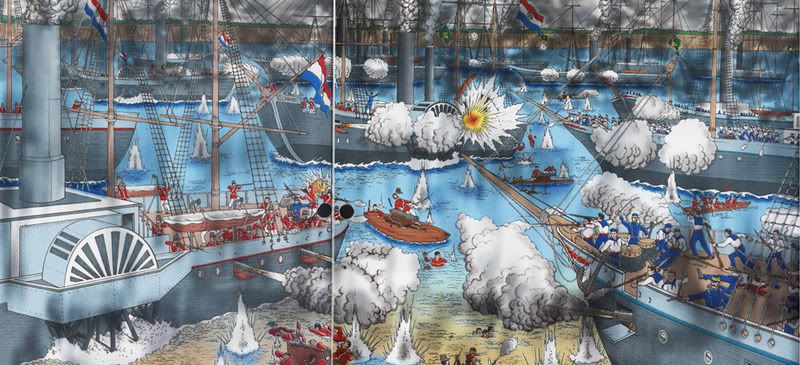

Riding down with the three-knot current were fourteen Paraguayan vessels - eight steamers and six flat-bottomed barges towed by the ships and each mounting an eight-inch gun. The total firepower of the Paraguayans was forty-seven guns, and like the Brazilians, more than one thousand soldiers augmented their crews. The lead vessel was the Paraguarí, a modern iron-plated warship with eight guns. Rear guard was the Tacuari, flagship, with fleet commander Pedro Ignacio Meza. And just ahead of the Tacuari rode the Marquês de Olinda, her Brazilian colors struck months ago (and made into a floor rug for El Presidente's office at Asunción), her old decks bristling with eight pieces ready to blast the ships of her former owners.

The Brazilians began to clear for action, their engineers and firemen hastening to get steam up, but they had less than fifteen minutes between the alarm given by the Mearim and the first cannonade from the Paraguayans as they passed their anchorage. The Paraguayans made their run down a channel close to the west bank. The range between their vessels and the Brazilian warships was too wide to permit an effective bombardment, but the sound and smoke of their guns was invitation enough to combat. On the Brazilians' decks, drummer boys who but an hour ago had served at the altar in cassock and surplice stood boldly at their posts beating the rataplan. Whistles blew as men ran to quarters, with gun crews loading immediately, and soldiers were mustered on their decks in readiness to repel boarders.

Vice-Admiral Barroso had been on the Parnaíba and was rowed back to his flagship. Aboard the Amazonas, he and his officers soon saw the lead Paraguayan ship start to make her turn. Barroso, sixty-one years old this day, was Portuguese-born but had served in the navy of his country of adoption. He had thinning gray hair and a full white beard, but his eyebrows were dark, and beneath them were eyes as commanding as the rest of his features. To get a better view of the enemy, Barroso had climbed up onto one of the Amazonas's paddle boxes. As he stood there, he passed on an order to a midshipman: "Make this signal to the squadron."

Barroso glanced swiftly along the line of his ships. Then he addressed the midshipman with orders for signal flags to be flown with two commands: "Bater o inimigo que estiver mais próximo!" and "O Brasil espera que cada um cumpra o seu dever!"

The first command was for the ships to engage the enemy at close quarters. The second was inspired by the glory of Admiral Horatio Nelson's triumph at Trafalgar sixty years ago: "Brazil expects that every man will do his duty!"

As the Paraguayan fleet completed its turn and started back upriver, the Brazilian ships maneuvered into position in the channels between the sandbanks and islands and opened fire: One of the Paraguayan steamers, the Jejuí, took a shot through her boiler and drifted out of action; the remaining seven and the six barges closed for battle, breaking their squadron line, with groups of ships and gun barges making for specific targets. The Brazilian corvette Jequitinhonha was battered by three Paraguayans firing ball and grapeshot and by their musketeers raking the corvette's decks. The gunboat Parnaíba also found herself under attack by three ships, including the iron-plated Tacuari and Paraguarí, which fired round after round as they steamed up to the Brazilian with the intention of boarding her.

Within the great bend of the river, as the twenty-one ships and gun barges blazed away at one another, the air rapidly grew thick with the acrid yellow smoke of battle drifting past the fiery mouths of cannon and mingling with the soot and ashes spewed from ships' funnels. The opening stages of the Battle of the Riachuelo went badly for the Brazilians, for no sooner had they given challenge to the Paraguayans than they faced an additional threat: The twenty-two guns and Congreve rockets of the Paraguayan shore battery just north of the mouth of the Riachuelo opened up in support of their squadron.

The small crews of the chatas, one-gun barges eighteen feet long, concentrated their fire on the wooden hulls of the Brazilian ships, seeking to blast through planking to pierce a boiler or detonate a magazine. For the crew of one chata, the fervor was short-lived when a shot from a 68-pounder on the Amazonas struck the barge, igniting its explosives and blowing it to bits. This did not daunt the Paraguayans as they prepared to board their adversaries.

But here in the rising heat of battle as the Tacuari, Paraguarí, and the small Salto converged on the Parnaíba, and the boarding parties made ready to leap upon the foe with cutlass and machete, they made a terrible discovery: Those now waiting at the port of Asunción for news of a great victory had neglected to place aboard the war steamers the only indispensable items for the impending action: grappling irons.

"Damn them! Oh, damn them!" a sergeant aboard the Salto raged.

His soldier comrades near him, their breath fiery with shots of cana swigged before the battle, blazed forth with even greater curses.

"Damn the stupid bastards!" the sergeant screamed again, watching the Tacuari attempt to close with the Parnaíba. Two men made a desperate leap for the Brazilians' bulwarks, jumping from the Tacuari's paddle boxes; but, as the vessels were not grappled, the Tacuari could not keep beside the enemy long enough for others to follow. When the Tacuari stood off, the pair of boarders leapt back to her deck, lucky to escape the Brazilian rifle fire.

The Salto was screw-driven, and her helmsman was able to maneuver her into position and pass slowly alongside the enemy gunboat; in minutes the sergeant and twenty-nine others had boarded the Parnaíba, their battle cries drowning the screams of one Paraguayan who lost his footing and was crushed between the two ships.

The hail of bullets from Brazilian riflemen felled four Paraguayans, but the remaining twenty-five stormed across the Parnaíba 's decks. Supported by small-arms fire from marksmen aloft in the three vessels harassing the Parnaíba, the boarding party began to overwhelm those Brazilians on deck. Many Brazilians had already been driven to take refuge below during the repeated bombardments by the Paraguayans.

The Paraguayans won the fight on the decks: Within fifteen minutes they had control of the Parnaíba, the first prize taken for El Presidente this day.

The sergeant who had been in the thick of the fight was exultant. He spied the body of a drummer boy on the deck near the Parnaíba's funnel, and with his cutlass, he slashed the straps holding the boy's instrument. Jubilantly, he took up the drum and sticks he had pried loose from the boy's fingers and strutted along the deck, raising cheers from his comrades as he beat a triumphant roll.

And then, steaming through the swirl of smoke, riding the swift current, the Amazonas came down upon this scene of battle. She held her fire until the last moment, when her starboard guns blazed at the two nearest Paraguayan vessels, Tacuari and Salto. The port guns of the Amazonas were loaded with grape: With a flash and a roar, they raked the deck of the Parnaíba with a merciless tornado of shot that instantly downed three out of every four Paraguayans.

For four and a half hours the battle raged along the bend of the Rio Paraná. With their towering size and greater firepower, the Brazilians slowly began to prevail: The Jejuí was sunk; the Salto was beached; the Marquês de Olinda, the very sight of which spurred the Brazilian gunners, also took a shot in her boiler house and ran aground on a sandbank.

The Paraguayans lost three ships and two chatas, but still the battle was undecided, for the Brazilians were also mauled: The Belmonte was holed at the waterline and aground; the Jequitinhonha was stuck fast on a sandbank; the Parnaíba, too, was effectively out of action.

After going to the rescue of the Parnaíba, the flagship Amazonas steamed slowly up the channel exchanging shots with the enemy, though these cannonades were secondary to another objective of Vice-Admiral Barroso and his men. About a mile upstream, the Amazonas turned. Then, full steam ahead, her great paddle wheels churning the water, the Amazonas came down before the three-knot current. On and on she rode, belching black smoke from her stack and red flame from the mouths of her cannon, steaming directly for the Paraguarí, the newest vessel in President López's fleet.

She struck the Paraguarí amidships, her ram buckling iron plates, smashing through the enemy's bulwarks. The Amazonas's steam whistle shrieked, her decks vibrated violently, her engines raced at full power with a mighty force that shoved the Paraguayan steamer sideways through the water and onto a sandbank.

"Viva Dom Pedro Segundo! Viva Brasil!" the Amazonas's men cheered, as the frigate backed away from the crippled vessel.

Some Paraguayans had been hurled off the gunboat by the impact; some had abandoned her to swim to the west bank. But a dozen or so shouted back abuse at the macacos and hurried to clear the debris around a 12-pounder. It was a desperate defiance: They were enraged at the destruction of their ship, and afire with the knowledge that generations of Guarani before them had been called to stand fast against this enemy of enemies.

With the grounding of the Paraguarí and damage to a fifth gunboat, which was limping along with a hole in her boiler, the Paraguayan flagship, Tacuari, signaled: "Break off action!" Aboard the Tacuari, the squadron commander, Pedro Ignacio Meza, lay mortally wounded, one of a thousand Paraguayans killed or wounded this day, triple the number of Brazilian casualties. With the Tacuari holding their rear, the three remaining vessels steamed off and were pursued for a distance by two Brazilians, until they, too, dropped back, their crews so exhausted and equipment so damaged that they dared not risk a chase to the Rio Paraguay, where they would come under fire from the enemy's river fortresses. For the Brazilians, it was enough to know that with the destruction of Paraguay's fleet, Francisco Solano López was denied access to the Paraná.

But the guns at the Riachuelo were not yet silent, and for one Brazilian warship, the hell that had begun more than four hours ago was not over. The corvette Jequitinhonha had run aground on a sandbank within range of the twenty-two guns and the Congreve rockets of the Paraguayan shore battery. The corvette had come under so murderous a fire that of her crew of 138, fifty were killed or grievously wounded.

Twice during this brutal afternoon, two of the Jequitinhonha's sister ships came in under the enemy's barrage to attempt to tow her off the sandbank, but they had failed. Respite came almost seven hours after the commencement of battle when, bombarded by the Amazonas and other vessels, the Paraguayan shore batteries finally withdrew. With that ceasefire, some of the Jequitinhonha's crew sat down on her splintered deck and wept.

Below deck, in a stern section of the Jequitinhonha, were two men who had remained at their posts these seven deadly hours with no thought for their own safety. There had been no need for them to go on deck to fix in their minds the awful scene, for it was all around them - the broken arms and legs, the mutilated trunks, the ripped-open faces.

The older of the two men was Manuel Batista Valadão, lieutenant-surgeon of the Jequitinhonha. His assistant, twenty-seven years old, was Second-Lieutenant Fábio Alves Cavalcanti, and this was his trial by fire. The suffering around him was beyond his imagination. Four lamps lighted the cabin, their yellow glare increasing the hellishness of the scene visible to men waiting their turn on the operating table; the deck stained darker with blood and the surgeons themselves besmeared. A pungent smell pervaded the cabin, but for this the wounded thanked Almighty God: it was ether, which had not been long in use and would spare them excruciating pain.

At times during those seven bloody hours, Fábio Alves Cavalcanti had been numbed by the horror: He would look at Manuel Valadão, who worked quietly, steadily, and gain the strength to ignore the battle beyond. Sometimes Fábio would be suturing a tear in a man's flesh, part of him far away, at Engenho Santo Tomás, which had belonged to his family for generations. "O God, my Father, allow me to return there," he once prayed aloud, unaware that surgeon Valadão overheard him.

For Fábio Alves Cavalcanti, a grandson of Carlos Maria, the child who had been left fatherless when Paulo Cavalcanti was murdered by Black Peter and his band of runaway slaves, the flashes of memory in this cabin where men looked at him with eyes that craved death were immensely soothing. He saw the Casa Grande where he had spent his childhood; a grand old house built more than a century ago and filled with mystery for him. He associated Santo Tomás with his youth, for he had not lived there permanently for a decade: His father, Guilherme Cavalcanti, spent most of the year at their town house at Olinda, and he himself had attended school there, later matriculating at the medical school at the Bahia, until he had entered the imperial navy eighteen months ago. Now, as he stood in this place steeped with blood and with suffering men all around him, Fábio wondered about that decision and felt a longing for that valley of the Cavalcantis so distant from this carnage.

Fábio Cavalcanti's doubt was short-lived. When the shore battery's bombardment ceased, Lieutenant Valadão told his assistant to go topside and find out if the battle had truly ended. Fábio started off slowly along a passageway, his shoulders bent with fatigue.

"Tenente . . ."

The call came from a gunner lying on the mess deck. The man had been one of the first to be injured. He had been brought to the surgeons with multiple lacerations and both legs broken by the blast when one of the Jequitinhonha's 68-pounders had been put out of action by a Paraguayan shell.

"What is it, sailor?" Fábio asked, bending down toward the man.

The gunner reached out and with his unbandaged hand gripped the hand of the young surgeon. "Thank you, my friend."

Fábio Alves Cavalcanti felt his own surge of gratitude for the privilege of being there - amid the hell that had raged at the Riachuelo, where men as brave as this broken gunner needed him.