Henry Koczur, Hammond, Indiana

Henry Koczur left his East Chicago home in September 1932 at 16, believing that one less mouth to feed would lighten the burden on his family of eight. His father was out of work and sick with stomach ulcers; his mother had often to serve potato soup for breakfast, dinner and supper. Henry headed for California, "a land where I didn't think anyone could starve. Many times when the freight trains stopped at night, we'd light a match just to see what was growing in the fields."

"In Saugus, California, I was bumming a house for something to eat, when a forest ranger drove up in an ambulance. He told me to climb in. I asked where we were going. 'To fight a fire,' he said. He commandeered more men on the way up the mountain road. What authority did he have to do this? I asked. If the governor himself happened on the scene, he could force him to fight the fire, he said.

"We arrived at a camp, where a ranger handed me a double-bladed ax and a three-quart canteen of water. We hiked up a mountain in the Castiac Canyon. When I got to the top, it looked as though the whole world was on fire.

"We started to build fire trails from the top of the mountain to the bottom. Men behind us threw the brush to the side, so the fire wouldn't leap across the trail but it always did.

"One of the rangers, a Captain Durham, sent for a water tanker. We ran two-inch hoses from the truck to the fire and cut a new trail. Captain Durham told me to take two lengths of hose to a ranger, who was wetting down the brush. I was on my way to him, when another ranger ran up to me, telling me to drop everything and run for my life.

"Captain Durham showed disappointment, when he learned I'd dropped the hoses. After the fire passed us, I went back to retrieve them. All I could find were four chrome-plated hose ends.

"I didn't think we could put out that fire, but then the wind changed and helped us extinguish it. We remained on patrol for a few days, looking for any sign of smoke and covering the embers with dirt.

"I worked 12 hours a day for 20 cents an hour, very good wages then. And, boy, did we eat good, as much as we wanted, bacon and eggs for breakfast, meat and beans for supper. When the fire was put out and the work ended, we learned we would have to wait 30 days for our pay checks. I buddied up with a fellow named Jensen from Escanaba, Michigan. We decided we would go to Yuma, Arizona in the meantime.

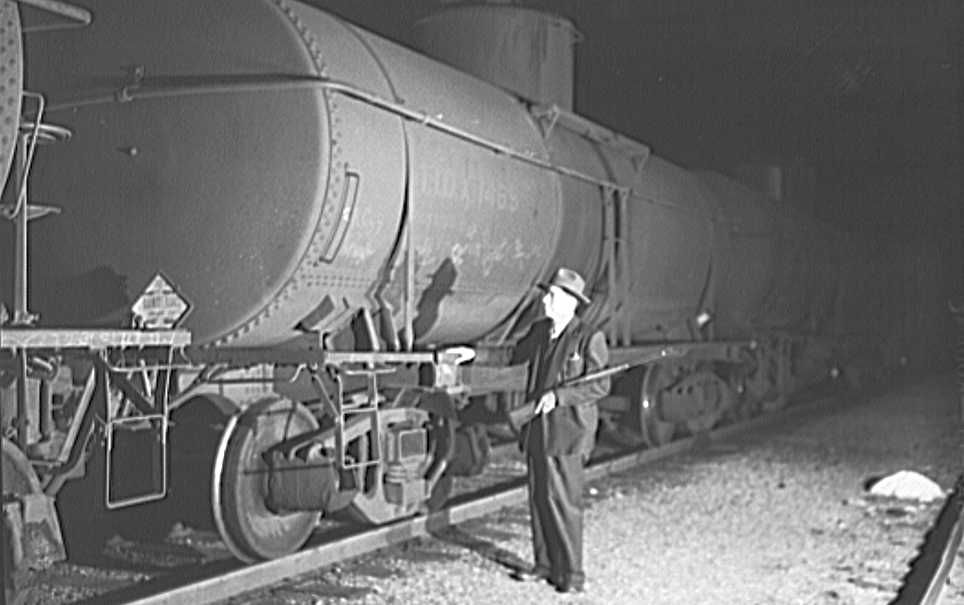

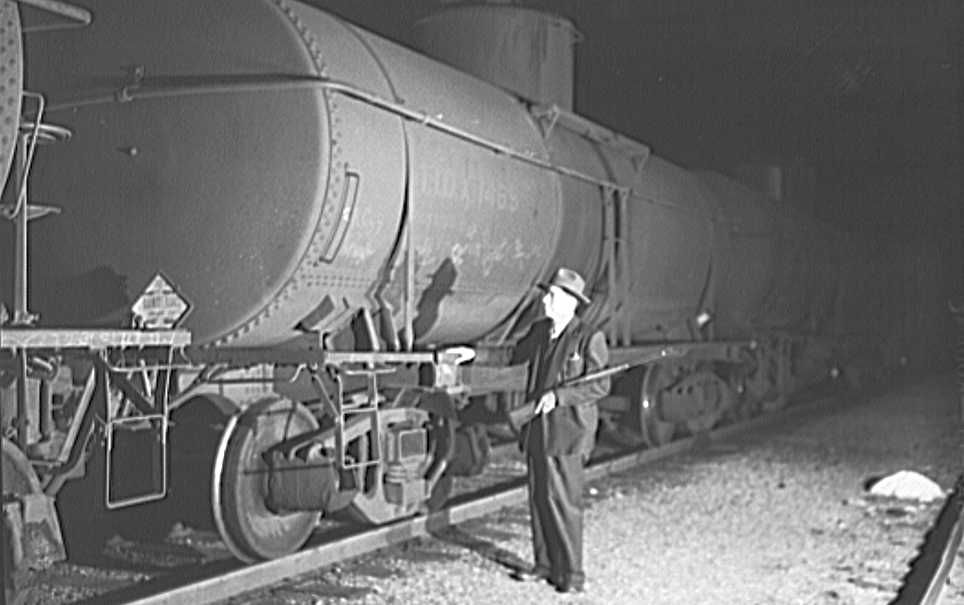

"We caught a Southern Pacific passenger train to Niland, California, riding the blinds with two other hoboes. When the train stopped, we all got off. We were caught by a railroad cop, who ordered us to line up next to the train. Had any of us tried to jump back on, I'm sure he would've shot us.

"When the train left, the bull asked how much money I had.

" 'Not a cent,' I said.

"One of the men who rode the blinds with us was next to me. The man had $2.00. The bull told him to take it out and hold it in his hand.

"The second man had 50 cents. My buddy, Jensen, had 20 cents.

"The bull collected the money. 'This will pay for your fare,' he said. He put the $2.70 in his pocket and told us to start walking.

"I tripped over a railroad tie. The bull thought I was trying to get away. He gave me a kick in the butt that to this day I never forgot. I saw he was going to hit me over the head with a blackjack. I raised my arm, and he struck my fingers, cracking the knuckle of my forefinger. He warned us to hit the highway and never set foot on railroad property again.

"We slept the night in the desert. Walking down the road in the morning, we saw a train being made up for Yuma. There must've been 50 hobos waiting there, who'd met the same fate the night before. We all climbed into an empty boxcar and shut the door, not making a sound as we waited for the freight to leave.

"All of a sudden, the door slid open. Who is looking at us, but the same bull who kicked and black-jacked me. 'Get the hell out of here,' he shouted.

"I was first to jump out and run. We were 100 feet from the train, when one of the bums hollered, 'Hold it, guys! There are 50 of us. He has six bullets in his gun. He knows he can shoot six of us; after that he's a dead man.' We listened to him. When the engineer gave the highball, we ran to the train.

"Almost all climbed back into the boxcar for the ride to Yuma. We left the bull standing there, with his legs spread out and his hands crossed over under his arms. "

Irving J. Stolet, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Irving Stolet took off from his home in Chicago in October 1936, heading south to Florida with a school friend. -- Irving, 16, would be gone for two years, six months of which he spent on the road. -- Before he reached Georgia, Irving and his friend were separated, as they ran to catch a freight. Traveling on alone, Irving rode into a night of terror in the Deep South.

"It was around 2.a.m. I was riding in an open gondola in Georgia, near the border of Florida. I was cold, tired and beat. The gondola was loaded with iron ingots, not a safe place to lie, but I was so exhausted I fell asleep among the bars of steel.

"About 3.a.m., the train stopped in a dark woodsy area. Out of nowhere, a flashlight beamed in my eyes. I heard a growl, 'Get out!'

"I crawled out onto the siding and joined a group of about 20 guys, all black people. I was told to line up near the end of the line, next to a white-haired black man. Meanwhile, the railroad bulls went on looking for more hobos up and down the train.

"There were some dark woods about 40 yards off. The old man punched me in the ribs and said let's make a run for it.

"We took off together. I heard a couple of shots and the old man hit the ground. I thought he'd been shot but he was just reacting faster.

"A bull came up to us and started kicking the old man. He kicked him everywhere till he was like an empty sack.

"I lay petrified. Finally, the bull turned to me, grabbed me with one arm, hoisted me up and slapped me open-handed. I saw a blossom of stars and flipped clean on my back.

"They herded us towards a couple of touring cars and pushed us in like sheep. They locked us up in a small country jail. I was given a cell to myself. The black guys were shoved into the remaining cells, six or eight crowded together.

"Next morning, the jailer's wife brought me a plate of beans, cornbread and black coffee. I was fed twice a day for the next three days and fattened up somewhat. The third day, I was sitting in my cell playing my mouth organ, when a pimply-faced white boy doing janitorial work whispered to me.

" 'Hey, kid, I can get you turned loose. Got any money?'

"I'd two one dollar bills hidden in the toe of my shoe. I heard that a county judge would be holding court: For blacks, the usual sentence was the chain gang. I didn't know what a white kid would be sentenced to, but I was worried about being kept in jail. I dug out those two stinking bills and gave them to the punk, hoping I wasn't being suckered.

"The next morning, a scraggly old character showed up and held court in the jail office. The blacks were lined up. I heard him sentence one and all to time on the road or at the pea farm.

"Then my turn came. The judge looked at me a couple minutes, didn't say a word, and then said: 'Get your ass out that door!'

"It took me a moment or two to comprehend; then I was gone.

"I walked through the village to the railroad and kept walking south. Ten to 15 miles down the track, it was getting dark, when I saw a small shack, with smoke rising from a stove pipe. I figured to ask for a handout. The shack was no bigger than a chicken coop and dark.

"An old black man answered my knock. I asked if he could spare a bite to eat. He looked at me a moment and said come in. There wasn't much of a home; a lantern, a small wood stove and a cot. The stove had a pot of black-eyed peas warming up, only about two inches deep.

" 'Help yourself,' the old man said and gave me a spoon. I swallowed the peas in no time and left. All I could say was thank you, but to this day, I believe I ate his only supper."

Gene Wadsworth, Sequim, Washington

When Gene Wadsworth caught his first freight at age 17 on a winter's night in 1932, he'd never ridden on a train before. Orphaned at age 11, Gene was living at Burley, Idaho, with an uncle who had five children of his own. "Why do you hang around here, when you're not wanted?" one of his cousins asked him. That night, Gene stuffed his few belongings into a flour sack and hit the road.

"I was about as low as a kid could get, as I walked over the Snake River Bridge. I was thinking of suicide, looking down into that black water, but I kept walking. A freight train was just pulling out of a little town. I stopped to let it pass.

"I'll never know why I reached out and grabbed the rung of the boxcar ladder. I climbed to the catwalk. I lay on my stomach and hung on for dear life, as we rumbled off into the night. I was scared stiff."

Taking the advice of older hoboes, Gene headed south to warmer climes and transient camps established by the government, where he could get work at $1 a week, plus food and shelter. Moving between camps in California and Arizona, he made friends with a young man in the same position.

"Jim was also blond, my age and size - six feet and 165 pounds. Everyone believed we were brothers. We thought a lot alike and hit it off very good. We teamed up and decided to make our fortune together.

"All went well with us, until one night when Jim and I were riding on the ladders between two boxcars.

"It was so cold my hands nearly froze. I slipped my arm over a rung of the ladder and put my hand in my jacket pocket. Being back to back, I couldn't see Jim.

"All of a sudden the train gave a jerk, as it took up slack in the draw bars.

"I heard Jim let out a muffled moan, as he fell. I whirled round and made a grab for him. He had on a knit cap. I got the cap and a handful of blond hair. Jim was gone. Disappeared under the wheels

"No way could Jim survive. I got so sick I'd to climb up and lie on the catwalk.

Norma Darrah, Seattle, Washington

Norma Darrah hopped her first freight at Owatonna, Minnesota, on a bleak winter's night in March 1938. Eighteen-year-old Norma was traveling with Curly, her husband of seven months, and his 13-year-old nephew, Harry Long. The newspaper Curly worked for in Kenyon, MN, had folded, leaving him out of work. An older brother, a carpenter at Casper, Wyoming offered Curly an apprenticeship in the trade.

"We gathered a few warm clothes, a frying pan, a pot, three small pie tins, some knives and forks, my husband's rifle, shells, and our bedding. We had three one dollar bills for the three of us, which we hoped would last until we reached Casper. What a vain hope that was!

"When the freight pulled out of the Owatonna yard, we unrolled our bedding and fell fast asleep. Imagine our surprise and chagrin, awaking in the early morning to hear the train whistle, as it pulled out of a station leaving our boxcar behind. We were sidetracked only 50 miles from our starting point. Talk about inexperienced hoboes!

"The next freight we caught took us to Sioux City, Iowa. We'd already spent most of our $3. I said I would ask the merchants close to the tracks for a handout. Curly didn't want me to go, but I insisted. Brushing off my coat and brushing up my courage, I went into the first grocery I came to. I asked for day-old bread, or anything else we could eat. The owner gave me a sermon on how a young girl shouldn't be grabbing freight trains, even with your husband, and what kind of man is he, blah, blah, blah.

"I was turning to leave, when the grocer said, 'Wait a minute.' He went to the back room of the store and returned with a paper bag. I thanked him and hurried to Curly and Harry, a big grin on my face as I showed them the bag of goodies. The sack held ginger snaps, all so tainted with kerosene, we couldn't eat one. We went hungry that day.

"We left Sioux City on an open gondola that had four inches of snow on the floor, the only ride we could get. When the train gained speed, snow blew off a boxcar ahead, hitting us like a blizzard. We turned our backs to it; we kept walking in the bitter cold or we would've gotten frostbite. I don't remember much conversation between the three of us. We saved our strength for the business at hand, which was surviving.

"We got off at a small town called Plainview. We ran into three bums, who showed us into a building with a big stove used to dry sand for slick, icy tracks. The sand poured out of a cone-shaped pipe and covered a large circular area on the floor. My husband, little Harry and I joined the three bums on this warm, soft cushion, all of us lying like six petals on a daisy.

"The night watchman roused us early the next morning, warning us to be on our way before the railroad dicks caught us for vagrancy.

"It was midnight, when we reached Chadron. Curly had a severe migraine attack. Harry and I left him lying in a boxcar, and went to check out the station. I was looking around the platform, when I heard a voice behind me: 'What are you doing here?'

"The man shone his flashlight in my face. I realized that here was that mean old railroad dick I'd been hearing so much about from my husband. He started asking me questions. How old was I? Where was I born? Why was I riding the rails? I told him we were on our way to Casper, Wyoming, where we hoped to get work. Where's your husband? He started in all over again, and I got mad!

" 'Why don't you ask my uncle?' Harry said. He was standing behind the railroad detective. He told the man that Curly was lying down in a boxcar.

"When the detective saw Curly, he asked if he needed a doctor, but my husband told him he only had a headache. He questioned Curly; then said he believed our story.

" 'Don't let me see you getting on this train.' He turned his back on us and never looked our way again.

"Harry and I climbed into the boxcar, getting as far back as we could. We thought we were going to the 'hoosegow,' for sure. Instead, we'd the good fortune to run into a railroad dick with a soft heart!

"At Crawford, we all piled from the boxcar and went to a hobo jungle across the tracks. The hoboes had a fire going, with a big stew pot. An old hobo offered me some coffee in a dirty tin can. I didn't want to refuse his fine gesture, and took a sip. The worst coffee I ever tasted in my life. I swallowed it and prayed to God it wouldn't make me sick.

"The old hobo lifted the lid from his stew pot. I saw all kinds of vegetables floating in a greasy mess. The carrots still had their green tops on them. The hobo asked us to stay and eat stew with him, but I caught my husband's eye. 'Thank you kindly,' we told him and left, saying we wanted to look the town over.

"Toward 11:00 a.m., I could hear my stomach growling. The longer I sat there, the hungrier I got. I pointed to some houses near the tracks. 'I'm going to ask for food,' I said.

" A lady came to the door with a child in her arms. She looked me up and down. I felt shamefully aware of the dust and dirt on my coat, my muddy wool-lined ankle snow boots. I wanted to run, but my hunger was stronger than my shame.

" 'Lady, I haven't eaten for days. I'm awfully hungry.'

"She looked me up and down again. 'We've already had our breakfast,' she said. 'My husband won't be home for lunch for an hour or so.'

"My heart sank, as I realized she didn't want this dirty homeless-looking creature in her kitchen.

" 'Lady, please, I don't want to eat with you. I thought you might be able to spare a sandwich.'

" 'How would you like a scrambled egg and bacon sandwich?'

" 'Oh, yes,' I replied. 'That would be a feast!'

"This very kind woman fixed two hot sandwiches for me. I thanked her with all the gratitude I could put in my voice without crying.

"I went back to Curly and Harry. I offered my husband a sandwich; he wouldn't take it, even when I begged him to. 'If I can't go for my own food, I shouldn't eat yours.' No matter how hard Harry and I tried, Curly wouldn't change his mind. Harry and I ate the sandwiches then, in short order!

" 'Aunt Norma, you did so good bumming, I'm going to see what I can do,' Harry said. He came back with a bag of tiny sandwiches left over from a bridge party, which the ladies of the town had held the day before. Well, even Curly couldn't refuse this time.

"Late that night, we caught a boxcar from Crawford, rested and with fairly full stomachs. We awoke the next morning, as the train sided our boxcar at Lusk, Wyoming. The stationmaster told us that there was no freight from Lusk to Casper. We would have to hitch-hike the remaining 90 miles.

"It was just one weary, hungry mile after another. Late afternoon, my husband took his rifle from his pack. We kept our eyes peeled for a jack rabbit in the fields bordering the road. 'There's one!' my husband said. He brought his rifle to his shoulder, took quick aim and shot it. Curly started running; before he reached the rabbit, a hawk swooped down and grabbed it. Harry and I were so mad; we were nearly in tears.Donald E. Newhouser, Gary, Indiana

Born on a farm in Nebraska in 1916, Donald Newhouser rode the rails from 1935 to 1938, following the harvests through the West, the hay fields in Colorado, potato picking in Idaho, apples in Washington, hops in Oregon.