OREGON

Herbert Sackett

16 - 1932

We were the poorest family in the area with twelve children. But then, most families in Grays Harbor County, Washington felt the same way.

The only jobs available to many people including youth and children were in the crops. Ours was considered borderline country and the two important crops which provided jobs for young people were in peas and strawberries.

My friend and I decided to go to the Puyallup Valley to pick berries. He was a little older than I and experienced at "riding the rails." I was sixteen and a novice. We traveled light - no money, no suitcase. I did have a loaf of bread.

There were "bums" hopping the freight trains, too, which made me apprehensive. But one of the men, sizing up my situation, gave me a dime. Evading the railroad "bulls" could be scary, too. Some got quite rough, though others looked the other way.

At the farm where we hired on, we were given a rough cabin to sleep in. It didn't take long to decide to return home.

I never rode the rails again but my friend continued. One day his body was found beside the railroad tracks hardly identifiable. Whether he had fallen off a boxcar or had been pushed, the authorities never determined. The authorities assumed that he fell off the train since he had epilepsy.

OREGON

Howard Pietsch

Hitchhiking was my primary mode of transport

To get back and forth from college and to music camp in Interlochen, Michigan. Plus trying to find a permanent job after graduation

40,000 miles total in 1933 to 1936

Another time decided to start hiking from Northfield MN to Interlochen MI, about 750 miles at 9.30 in the evening. We had made only 50 miles before daylight and learned later a driver, who had picked up a hitchhiker in the area, had been murdered a couple of days earlier.

Trust: Two women picked them up, arranged dates, loaned them their car!

OREGON

James Gambill

My father and I left Little Rock, Arkansas when I was eleven years old in 1927 and hitchhiked around the country for five years finally settling in Houston TX in 1932.

“Those were hungry times.”

My father was a school teacher and had been a school principal but he could not find a position. We worked where we could find it, mostly as farm hands. I made the same wages as my father, one dollar a day and board.

Hitchhiking was our mode of travel for he felt that riding the rails was too dangerous for me at that age, 11 through 16.

OREGON

Jan van Hee

1937 Came from Holland age 9 1/2

"I was a throwaway child."

My mother blew up at me. I left a note. I'd be back when I had a car.

I was 19. I must've looked like I was 12.

"As a teenager, small and young for my age, I had to be on the lookout for yeggs, chicken hawks and jockers. They could be really bad news."

"Chicken hawks": older guys who'd try to rape you. A "wolf" was one who tried to sugar you up

I joined gang of teenagers. "Big Jerk" ruled us with an iron fist. I'd hopped off a train to avoid a chicken hawk.

Train stopped half a mile away. I'd tricked him. He came and got me and was holding me by the shoulders.

Big Jerk's gang came to rescue: Wanted to know if they should kill him or not.

With gang, when I cut my head, I remember getting my wound stitched with coarse string. I still have scar to this day.

Thrown from top of box car at 30 mph. Saw many bloody fights, a shooting and a bo cut in two by wheels.

Watched two bo's cut up a very mean bull.

Spoke to a bo who was riding the rods and was badly messed up by a shack who tied something steel on line and trail it under victim... bounced around hitting him and threw chunks of gravel on him. He had broken ribs, broken ankle and was a mess of brown and green bruises plus long gash on his scalp. Lucky to be alive.

While in university I never heard mention of homeless kids.

You could tell a lot by the clotheslines.

Marathon dance: We were like trained mice - 8 hours at a stretch.

Due to my small size and strange accent, there were usually about ten or more disappointments than successes.

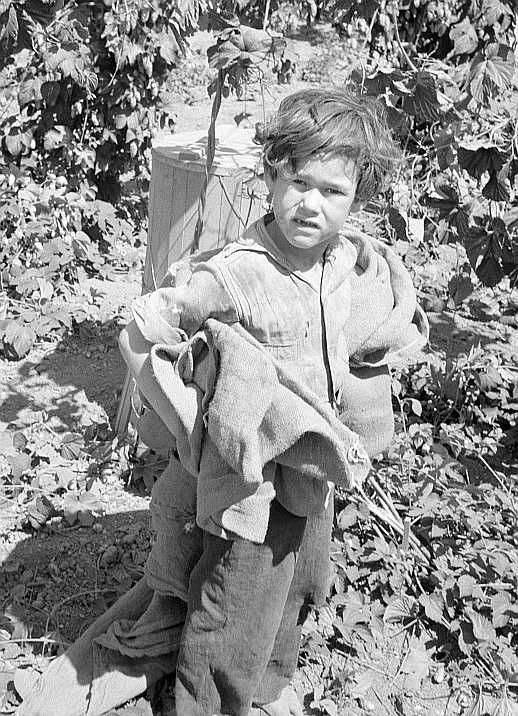

I walked hundreds of miles along rural country roads looking for work. Farm labor was all that I had been trained for. There was always news of some work “over there” or “up the line” but very few materialized. On farms, youngsters were sometimes resented because they were taking the place of an adult who might need to feed a family.

OREGON

Jim Reid

Started riding at 14, when he left school

There were so many people riding freights in the 30s… Damn few people that had anything at all. Refused to share it. Most grocery stores would give a bar of soap, nothing else. I’m 71 years of age and until this day, I still hate the Salvation Army for several reasons.

OREGON

Noami Trout

A grim life… Born 1910

“Carlos, my brother, shot rats at the flour mill.”

“When I was 12, I quit picking coal by the tracks as I was a mother’s helper. I delivered a baby that summer for a neighbor.”

“Papa went out on the big railroad strike of 1923.”

In May 1931, my husband was out of work and could find no other job. He got a ride to his father who worked as a rug layer and upholsterer.

Lots of young families were splitting up in the same way, so it wasn’t so hard on their folks.

I left with my son and a hatbox. Three men said they would help me… one to catch the hatbox, one the boy and one me.”

Hobos collected and bought us a bus ticket after that terrible ride.

Finally arrived at Seattle and went to husband’s workplace:

His mother met us at the door and said she would keep us overnight, but that was all. Next morning my husband told me to get out and he needed any money I had. He tried to grab my purse but I told him it was empty except for a quarter.

He said Domino cigarettes only cost 10 cents so he could get two packs, but I fought him off on the street and he left us.

Went to my uncle’s place in the sticks. We were welcome though he hadn’t worked in some months. My boy and I made a pallet of Ozite rug pads in a closet and got some rest.

OREGON

R.L. Foster

In Seaside, OR we found a group of hobos who enlightened us as to where to sleep, and how to get food. They took us to an empty grain car and had two of us get in and get ready to slam the doors shut when a goodly amount of pigeons came in to eat the spilled grain on the floors. When a couple dozen came in we slammed the doors and started catching and killing pigeons.

The hobos had an old iron kettle that they suspended over a fire for cooking. They had onions carrots and other vegetables that they had appropriated from gardens. These along with pigeons made an excellent mulligan stew. We got our bellies full and had a nice dry boxcar to sleep in that night.

OREGON

Ross Butler

“The winter of 1932-1933 I missed school to work on a farm to pay off a debt owed by my father.

"They hired four men at $1 a day, and each man had to pay for his board except me. Since they applied $1 a day to the debt of my father they had to feed me to keep me alive and working.”

“My brother Glenn and I finally got caught in Boise, Idaho – riding the top of the Student Special that took students to southern Idaho for the Christmas holidays – and were jailed."

Graduated from University of Idaho, 1939 B.S. Business.

"I had hitchhiked in 1935 but drove back in a Cadillac in 1989."

High hopes and lean times.

Hobo "volunteers:" Fighting Fires in the Cascades

OREGON

Ross Coppock

1937/38

My own experience in the summers of '37 and '38 was not directly involved with "hoboing."

I served in the Forest Service during both of those summers, in the Mt. Hood National Forest, out of Hood River, a community on the railroad through the Columbia River Gorge. Our crews were based in Parkdale, near the North slope of Mt. Hood in the Cascades. Occasionally we were called on to leave our own forest and participate in fire suppression activity in the National Forests.

Since one of the area's principal railroads ran through the Gorge, it was possible for the local sheriff to stop a freight and commandeer all the so-called "bums" who were aboard. They were given the opportunity to go to jail as criminals caught on the trains or to "volunteer" to fight a fire that badly needed immediate manpower. They would be fed, bedded and paid.

Almost invariably, the men chose to fight fires. In those times the equipment was mainly back-packs with water pumps, shovels and pulaskis. Nothing very sophisticated, only sweat and back-breaking toil. These men were not always in the best of condition nor were they very adept at the task. Many had never been nearer a forest than the train they were yanked from.

My own group never stayed any longer on another forest fire than was absolutely necessary, since we were needed as the first line of defense on our own stomping grounds.

I did not see these men at work except in the hottest part of the battle and never on the clean-up phase. Some worked like Trojans, some were expert at the fast shuffle and what I later learned to call "soldiering."

Sooner or later they were brought back and placed on the quickest train out of Hood River, since our small town did not cotton to hundreds of unemployed men roaming about.

The Sheriff, John Sheldrake, was an out-sized man, most of it heart like a huge marshmallow. If a man refused to work, I doubt that John was too vindictive. He also knew that the county could not afford many non-paying guests for any length of time.

We residents were used to the men who rode the rails and dropped off at Hood River seeking work in the orchards when it was available. We often fed those who came around offering to work and gave out many a meal and some small change to a man or boy who sat on the back stoop eating a plate loaded with whatever our own luck of the draw was to be that day.

My mother and the other women were never afraid of whatever men turned up. There was no violence, nor outright thievery and many of the men were obviously down on their luck and separated from their families.

I have no doubt that there were the few who were "bad apples," just as they are found everywhere.

Our townspeople understood the reason most of those riding the rails were forced to do so and were not critical of such a nomadic mode of life. Seeing all those men and boys riding freights made me more determined than ever that when I left home I would go to sea. I never did. Go to sea, that is.

It has occurred to me that some women may have been among these knights of the road, though I can't recall ever having seen any. If there were, they were not pressed into fire suppression duty.

I found fire-fighting the most draining and challenging physical and mental torture that I have ever endured. It can be, and was, pure hell. Inevitably I would reach the point of exhaustion where I would be forced to collapse on the ground and if the fire "came and got me" that was going to be it. I can imagine what it must have been for those who really gave it their all, untrained and alone and scared to death.

OREGON

Steve Svetich

I hesitate to do this because much of what I am going to reveal to you I have not even told my family. But memories race across my mind, and if ever my story could be told it would be now.

I was born in 1917 in Bingham Canyon, Utah. It was a mining town and not the most desirous place to live. We were a family of seven. Our father worked in the underground mine. I was 11, when my father died in 1928 of miner's consumption, a lung disease.

I walked the tracks to pick up pieces of coal that fell out of the trains. I scrounged around the boarding houses for whiskey flasks. They were worth 5c and we knew the bootleggers who would buy them.

In 1932, mother and widower with nine kids married, making 15 in all. He was an alcoholic…

Rode rails to Oregon from La Grande…

OREGON

Weldon Patton

17, with two other boys 15 and 16

Jumped freight in hometown of St. Cloud, MN to ride to Wenatchee, WA, seeking work in apple orchards.

Got a job for 22 ½ c an hour with American Fruit Co.

“I have never told this story to anyone. I was ashamed of my humble beginnings. Maybe it is time to tell it to someone.”

OREGON

Wes Rimel

Tragedy befell a cousin of mine. He was in his teens in the 1930s when he learned of a job in a nearby town. Assured of employment is he could be on the site by a certain time, he received $5 in cash from his father, who cautioned him to hitch hike rather than hop a freight.

Days later, his body was found beside the tracks. He had been rolled and killed for the mere $5

OREGON

William Berg

rode 22-23/ 1933-1934

At a railroad junction in Ohio (or was it West Virginia?) I fell in step with a black teenager whose right forearm was bandaged with a soiled piece of shirt. The fellow didn’t respond well to my attempts at conversation. He seemed embarrassed. Finally, perhaps sensing that I was for real, he opened up, showed me his arm badly burned by steam deliberately spewed out just as he was passing a switch engine. I covered the burn area with Vaseline and suggested he discard the dirty bandage. The boy appeared grateful.

“I got an ugly spot on my head, too,” he announced, doffing his cap. Two square inches of skull showed up.

“How did that happen?”

“I was standin’ up on a freight car lookin’ the wrong way when the train went under an overpass. I didn’t duck in time,” he finished, looking foolish.

I clipped some of the hair round the wound and smeared it with Vaseline. Each of us went our way.”

Chicago World's Fair visit:

That fair was the most astounding event of my life to that date. Four days and three nights I spent on the grounds.

As the crowd thinned out I would retire to a flat slab in the lakefront breakwater. It had a sheltering flat rock jutting out above it making my boudoir invisible from three sides. Each morning I would strip and lower myself into the lake for a few refreshing moments, dress, make a breakfast from any food left over from the night before, and sun myself or write in my journal until the crowd became large enough that I would not be conspicuous. The world was wonderful. Life was good.

“Get out of overalls buddy. Nobody ever made any money wearing overalls.”

Ripped off of a third of my life savings after less than a month on the road. -- The knife trick, the city slicker and country bumpkin.

Royal Gorge: walked back and swam in the Arkansas River. I plunged into the liquid ice for a quick dip. I emerged in a matter of seconds gasping and with an advanced case of hypothermia. I lay in the hot sun for two hours before I could stop shivering.

Hurtling through an electric “storm” in the dead of a prairie night, sitting on the catwalk of an oil tanker… Darts of light… I surmised whole prairie was electrified, and wondered how much danger we were in. It wasn’t until weeks later in northern Wisconsin that my acquaintance with fire flies solved the mystery.

A daughter dressd in a flour sack and a flock of starved, crazed chickens... I could stay here, I mused, marry the buxom blonde, eventually become manager of the bakery. The dream was rudely shattered when I learned that the surly delivery truck driver had not only the same idea before me but had successfully accomplished the first two steps.

Did I know how to stook grain? Yes, I said that I knew. I quickly learned I didn’t have the slightest idea what stooking meant.

When I look back on those days of the road realistically, I can recall shivering nights sleeping in the open or in boxcars, or worse yet under filthy blankets in shelters or boxcars, or of fighting off a light-fingered dandy who tried to rob me in my sleep.

But when I look back on the total experience itself, I regard it as one of the happiest years of my life, certainly the happiest to that date. Why? I’m not sure, but I believe it may be the freedom to do as one pleases, and the challenge of living, knowing that one will survive, but gleefully anticipating the revelation of “how?”

OREGON

William Hendricks

1932, graduated from De Queen Arkansas High School

I left home with 50c in my pocket and carried a small bag, which contained a change of clothing.

At a grocery store I saw that cans of pork and beans were on sale. Six for 25c. I bought $2 worth.

I caught a freight thinking that at Wenatchee, WA I could get a job picking fruit. Crossing Montana, I ate pork and beans. About 125 miles from Whitefish, Montana, the train blew a cylinder head. All of the freight cars were put on a siding and the engine and caboose left for Whitefish.

All the people of the empty cars got off. I counted over 400 people, men, women and children and babies who were stranded with me. The only water we had was from ice that was in a fruit car.

I had some pork and beans left but I didn’t share with the people as I had such a small amount. I would slip aside and eat where they didn’t see me. After four days all of my pork and beans had been eaten.

Most of the people started walking across the fields to a road where we could see cars going in both directions. I remained with the train. Just as the people got to the highway, an engine and caboose arrived, hooked on the empty cars and took us towards Whitefish. All the people on the highway tried to get back but never made it.

A teenage girl was followed by six or more young teenage boys. She would kiss and hug first one and then another. On an empty coal car the boys would take turns having sex with the girl. If any got pregnant she would never know who was the father of her child.

At Wenatchee I saw that all of the apple trees were loaded with fruit. I asked several owners to let me pick apples. I was told that in 1931, they had picked all of the apples, put them in crates and sold them for less than the crate had cost them, let along pay for the pickers. They were going to let the apples fall onto the ground and rot. At least the rotting apples would be of some benefit to the soil. They did tell me I could pick as many apples as I wanted for myself.

At Portland, I went to three houses seeking to work for a sack of food that I could take for journey to Klamath Falls, but several women made me eat a meal.

“The food was very good but I was in misery when I left there. By the time I reached the freight yards I had to vomit. All that good food went to waste. By the time I reached Klamath Falls I was starved."

Hired by a man to dig a ditch at 50c an hour. “After we had been digging for several hours another man wanted to know what were doing digging up the Insane Asylum yards.

At Los Angeles, a tall muscular man asked, “Are you prepared to die?" It scared the stuffing right out of me. He went on to say that he was the second Jesus Christ.

I still could find no work back in De Queens. I asked the College of the Ozarks for a job in order to attend college in the fall but this was not enough to pay for clothing, room, board or my books, as I would only get 18 cents an hour.

Two hours were to be spent in the milking of sixty Jersey cows with another boy helping me. It took more than two hours a day to milk them twice.

I was the college butcher and on Saturdays I killed two steers and a hog for the college. Sausage out of the hogs. My college profs had me kill and dress their beeves and hogs and for this I would get 50c per animal.

I washed dishes for the cafeteria at night. Another part time job was selecting trees in the woods and bringing them to the college and setting them out. After 55 years they are giant-sized trees now.

I joined the Arkansas National Guard and for each drill I would get $1 or $12 every three months.

In my classes I made nearly all As and rest were Bs. I graduated as a chemist, B.S.Degree. When I went through the graduation line I was given a piece of paper saying that as soon as I paid the college what I owed then I would receive my degree.

After graduation I hit the rails once more. I sought a job as a chemist. I was asked by at least 20 prospective employers: Why should we employ you when you have only a BS degree. We can hire a chemist with a PhD for the same price.”

I couldn’t give them an answer. I did manage to exist as a part-time butcher.

I went into the army on September 1, 1938. On Nov 16, 1941, I resigned and got a job working as a chemist for the Department of Agriculture. On December 7, we had Pearl Harbor and by July 21 I was back in the army.

In combat in northern Burma in 1941, I was wounded three times. After the war was over I went back to my work as a chemist for the Department of Agriculture. I retired in 1973.

Before I retired I went to Klamath Falls and bought the house I now live in. Thus I have retired in the town I learned to love in 1932 when I was a hobo.

PENNSYLVANIA

Angelo Sorrentino

20/21 1933+

from Paterson NJ…

“Coming out of Chicago train slowed down. A stranger ran alongside the car. Train began moving rather fast. He hooked on to the door tracks. His feet left the ground and he dangled in mid air. In friendly concern I offered my hand and got him aboard.

We talked awhile. Suddenly he asked me: Do you have any money? I had some but said no. He pulled a hunting knife out of a sheath. Let’s find out, he said.

Quickly I reacted. I grabbed his arm and charged. He never expected it. I kept my feet moving and pushed him through the open door. The train by then had picked up speed. I barely held onto the frame of the door.

I never found out what happened to him

PENNSYLVANIA

Ann Walko

During the Great Depression we lived in a corner house that just about jutted into the Eastbound section of The Pennsylvania Railroad. Lots of soot and lots of cinders and lots of work. Until the Depression hit.

The Eastbound Hump of the PRR was where freight trains, going East, were broken up and rerouted to wherever: East, North east, Southeast. Big behemoth engines roared, chugged growled, and even chortled when being refilled with water from a huge pipe.

Traffic dwindled to one or two trains a day and even these were not capacity filled. Many box cars went through without freight, but, these became quickly filled, as men began looking for jobs.

Ann’s husband John, on the road:

He remembers seeing the tip of a house over a knob. A farm house. Maybe they have something to eat. He hadn't eaten for two days. He could almost smell the food. Maybe if he asked. Quickly he crossed the field.

Not until he knocked on the door did he see anyone. A lady opened the door, but before he could say a word she ordered him off the porch. "Get out," she cried. With a broom in her hand she almost pushed him off.

John cried to her that he's hungry; that he'd do anything for some food. "I'll work," he cried. "Anything."

"Just go," she cried. "No riff-raff around here." And John went. But only until he was out of sight.

After what he thought was a reasonable time he stole around to the back of the house. He might find something in their garden, or in a garbage dump. What he found though were cans of milk cooling in a trough. Picking up one of the metal containers, he carried it to a cherry tree, propped the can in the crook of the tree, climbed up, and feasted on milk and cherries.

When he had finished, he carried the rest back to the trough, filled his pockets with cherries, and stole away toward the highway.

But that night he vowed, "Never again will I steal to eat."

PENNSYLVANIA

Casimir Brdcesak

I left Pennsylvania with $1, 3 cans of beans and a half loaf of bread. Got back home with 5Oc

In Hastings, Nebraska, I got a lift with a trucker. I had to unload 15 tons of ground marble. When he stopped to eat, I got a hot dog and he ate chicken and ice cream.

From Denver most hobos detoured away from the Moffat Railroad Tunnel and headed for Denver Colorado.

Transient camp at Gold Creek Canyon. It was 96 miles from Elko, NV. Worked for $5 a month building a road through the mountains. There was a small town 10 miles from the camp and it was a cowboy town. They had a dance there but we had no money so we sat and watched the dancing and the music consisted of a piano and violin.

After the month was over you had to wait two weeks for your check. They took us back to Elko, then put all of us on a truck and took us to Reno like a bunch of cattle.

Trying to get into California in 1934, the police were lined up with tommy guns because the place was flooded with people looking for work.

Traveling through California there were signs "25 cents for all you could eat" but nobody had the 25c. Some days you lived on tomatoes, cantaloupes, watermelons, whatever you could get your hands on.

PENNSYLVANIA

Don Davis

We never really belonged. The difference was that we could go home. Out of the thousands and thousands of kids on the bum most of them could too.

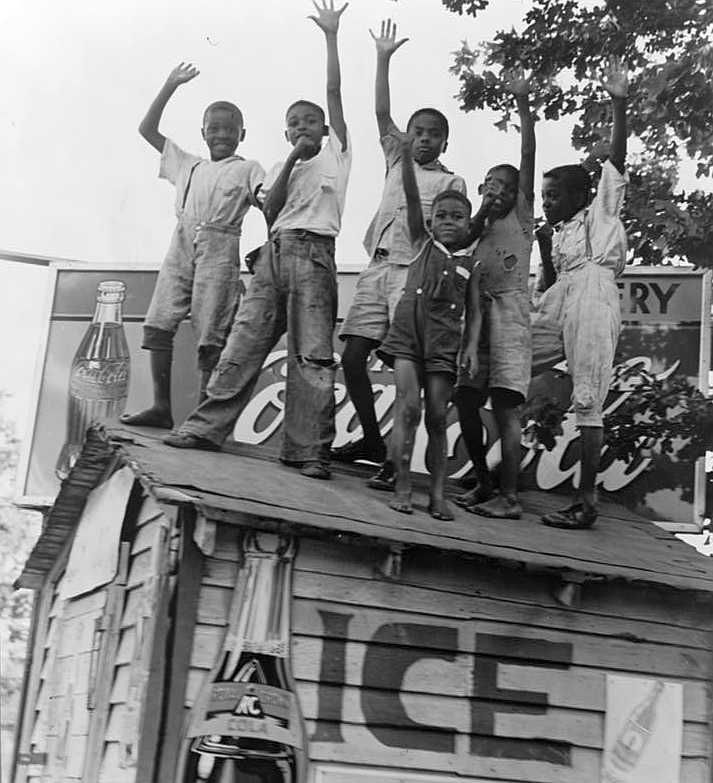

But there were the completely lost and dispossessed. Their old man couldn't take care of them and the country, based on a Ben Franklin economy, was too newly shot to take over the job. In a community where you were well known it was almost impossible to keep going to school, for instance, when there was no way to maintain even a pretense of half decent living. It didn't take much to send them on the road.

Our own motives were simply the leave-the-nest urge of all early teenagers, heightened by the knowledge of those already gone from home with or without parental consent.

We also had at least the beckoning intention of seeing the Chicago World's Fair.

Certainly there were trucks and even cargo-bearing airplanes, but the railroads were king, far beyond what today's youngsters are aware of, and like fleas on a dog they carried us with them.

Naive and fearful, overruled by ignorance and bravado, we walked to a town siding, boldly caught a slow moving freight shuttle to the local yard and escaped the first of a series of horror stories we learned in the days to come.

Ahead of iron-topped bridges, tunnels, and signal structures, there were heavy warning strings hanging from a crossbar extending over the tracks...

Happy and enjoying a brand new travel view from the top of the boxcar we were riding we were only annoyed by those strings as we rode through them.

It was only when Louis screamed "Duck!" that we dropped to our bellies and looked back at what we had gone safely under, sober as a drunk in shock.

We began with thirteen dollars between us. Most of that went early -- it takes time to learn the tricks of even such a haphazard trade as hoboing -- and the rest went inside the Fort Wayne county jail.

The legal charge was destroying railroad property and while accidental was true enough. The judge gave us a weekend and it was only later that we found out we had luckily escaped thirty days at the county 'poor farm.'

The illegal charge came from the inmates, the leader of whom was reputedly in for murder, although that was probably just to intimidate us further. They held a brief kangaroo court and fined us just the amount we happened to have left. We were not about to protest either sentence.

We also had two old half-sized valises. I lost mine somewhere in Michigan when the rope over my shoulder broke as it banged against the side of a fast-moving freight that our improving talent enabled us to catch.

Louis later had his 'stolen.' Neither one of us regretted them much for we had come to appreciate the ancient mariner and his albatross. Pockets and the inside of a shirt will carry almost as much.

Youthful energy and impatience have the odd effect of leaving youngsters unimpressed with what they later look back upon with almost wonder.

The sight of Niagara Falls for instance was nice but couldn't be compared to the rattling ride from Jamestown to Buffalo through the New York grape country.

And while we were admittedly denied most of it, (the Chicago World's Fair) it didn't seem like much more than a giant carnival at the time. Our only souvenir was a string of booth self-portrait snapshots. We were far more amazed at the outlying stockyards.

Sleeping, a place to sleep, was not a big problem to healthy sixteen-year-olds especially with acquired knowledge. It's strange how many buildings, public and private in country town and city, were left open or only superficially closed at nig

Remember now, these were unique times and I strongly suspect that fire houses, police stations, and similar places were more or less unofficially expected to be used by us. At least I can't recall any hardened 'tramps' there.

One incident made us laugh a little nervously the next morning: We had found an inviting open shed set back on the grounds of an apparent estate and used it for the night. Our laugh came when we discovered we had slept at the 'estate' of the criminally insane

But most of the sleeping was in traveling. Empty boxcars, gondolas, and the ice compartments of fruit cars always had cardboard, straw or burlap in them and once in a rare while there was a deadhead passenger car with its plush seats to dream in.

As far as the fabled hobo jungles were concerned, I think they were just that. Mostly myth. The nearest thing we ever saw to them was an occasional Hoover city and even they weren't much. Granted that we were no professionals and restricted ourselves to the east and mid-west and probably would have been rejected as nosy kids if we ever had found one, our curiosity had to be satisfied with stories. Stories that I'll always regret I never took notes on.

Many of them were told more or less factually and without the tears and histrionics of soap opera. Instead they were usually spiced with the wry humor of defeat. Mostly though, we heard accounts of bumming experiences either first or secondhand and some of those young people were natural entertainers despite the fact that most of the group were easily entertai

Riding the blinds or riding the rods -- neither of which any of us put much stock in -- were only a part of the horror story category. Others were a kind of warning account of accidents that had - or like our own first danger, could have happened.

Common tales with variations were rumors of beatings and worse, sadistic 'bulls' or railroad detectives, and southern road gangs. One of our own small contributions was being deported from Canada and mocked by U.S. border guards: "They don't want you wearing out the king's highways."

The 'we' I've been using usually refers to Louis and myself but obviously there was a lot of time spent with others, primarily in sleeping and traveling.

Gossip and the grapevine need people and there was no shortage of information among our own people.

You could be directed in surprisingly short time not only to the right track but the best place to catch your train. Any minor windfalls relating to the trade spread just as easily and after a while there was an indefinable label attached to 'members' almost as recognizable as a dog-tag so you can imagine what the adult professionals had going for them.

I can't recall us ever really bathing but we kept reasonably clean both inside and out with the aid of those same public buildings plus railroad and gas stations. But that and whatever other problems we had were relatively minor.

Like all living things we all had to eat. Starvation is an ugly word but greatly exaggerated. Even the prying media has difficulty finding examples. Food has always been plentiful. The challenge lies in getting it.

At first the thirteen dollars was it, but after the regular meals of our jail term we had to learn. Briefly, we learned quickly but although we sacrificed a lot of inhibitions and Sunday school precepts our morals were never seriously strained. In fact, Louis later entered the priesthood.

City hoboing was distinctly different from rural life because while there were more opportunities there were also the dangers of vagrancy and general suspicion.

Country and small town gatherings like generous picnickers took place in spite of the times and the old trick of offering to work for a handout usually produced the latter without the former. But cadging and bumming - scrounging had not been invented yet - did teach us one philosophic truth: the difference between a good life and a poor one is the ability and means to choose.

Our age, both the era and personal years, undoubtedly had much to do with it but we never really suffered. One short summer was not time for sickness, although we saw it, and certainly not enough to get discouraged. But I've often wondered what marks were put on those who could not go home.

PENNSYLVANIA

Edward Hrabina

“I was in my teens and it was no fun.”

Rode from age 16-19. 1929 to 1931

In Oakland CA, a passenger train went over him, when he fell; he got back on next train and rode for 300 miles. Found beside tracks by another hobo, who nursed him for three months.

PENNSYLVANIA

Harold MacNeilly

(Article in Dallas Morning News/ July 16, 1989/Delaware County Daily Times, July 12 1991)

1932

“Jersey Red”, a fine broth of a red-haired lad hopping freights and seeing the country. Hopping rides through 38 states, for eight months.

“I ate good, slept good and had a hell of a good time. Just the other day I was watching a train go by and I started getting itchy feet again. Sometimes I think coming back home was the biggest mistake I ever made."

“I was 19 at the time, living in Camden and working in a Philadelphia department store for the princely sum of $6.45 a week. By the time I had paid my $3 per week room rent and 20 cents per day fare across the bridge that didn’t leave a whole lot to live on.”

After eight months, MacNeilly realized any fortune he might make wasn’t in the west. He rode the rails back home and returned to his job in Philadelphia, only now the salary was a stupendous $14 a week.

“The railroad detectives were called bulls and conductors were shacks. Locomotives were hogs and cabooses were buggies, crummies or cubs. Hobos themselves were known as bindlestiffs and they ate saddle blankets (hot cakes) and mulligan stew. Occasionally if a bull got angry, a hobo would get a jolt – a stretch in jail.” 326

Denver-Rio Grande conductor stopped freight train on a suspension bridge high in the Colorado Rockies so his ‘non-paying customers' could enjoy the view.

Town marshal in Roseville, CA, bought Jersey red a pint of chocolate ice cream in the middle of a heat wave.

Murderous railroad bull in Yuma, AZ, who knocked a hobo off a train one night, only to discover the next morning that he had killed his own son.

MacNeilly used to exaggerate a slight limp, the result of a childhood bout with polio, as he went door to door for handouts. When that didn’t work, he’d get a job picking dates and fruit or digging potatoes for a dollar a day, from daybreak to dusk.

Then there were the fine times in Provo, Utah, where the water was so pure you could drink it right out of the gutter.

Sent clipping, quoting Anne Benett of the Association of American Railroads: “The gentleman hobo has gone by the boards. Now they are killing each other. It is a kind of shame that hoboing is still being portrayed as something romantic. It’s not romantic at all.”

I am now 79 years old, troubled with emphysema, asthma, bad heart and prostate problems. But, mentally I still ride the rails and dream of the good times, the bad times and the tough times.

The rain, cold and heat, I still feel. The kindness of people you only saw but once and the cruelty of the railroad bulls and shacks. It was all part of life on the road and you accepted it all. I wish I could go back!"

PENNSYLVANIA

Jack Baxter

Served on a Georgia Road Gang

Started riding in 1932: age 17, from PA to San Diego with step-dad. Lost his belongings at beginning of trip, traveled in undershirt, dungarees, and sneakers.

Saw a brakeman knock a man off train; in Mobile, got on train with over 300 people.

Hobos were scared of reefers just then because several hobos had been found dead inside reefers in Klamath Falls.

On train from Mobile to Selma he was riding on an oil tank with his feet on a coupling. He fell asleep and his left foot got caught in the coupling. The engineer had to release him. He was on crutches for 3 months.

In Oct,1934, he was caught on a train in Georgia and sentenced to 30 days on a road gang. Cool Hand Luke conditions. Guys were sentenced to 30 days hard labor for throwing banana peels and riding bikes at night.

PENNSYLVANIA

Luther Head

East Tennessee: I lived near the railroad tracks which hauled coal from the Virginias to the Carolina cotton mills. The huge trains went through a tunnel on the Tennessee side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and came out on the North Carolina side.

There was a large limestone cave near the railroad which the hoboes used as a resting place on their way South. I spent many days inside this cave with the hobos.

The people of East Tennessee were very poor at this time, but always had a little something for the hoboes to eat.

I saw many dogs on top of the cars coming out of the Virginias with the hoboes. The people were so pressed for food, they didn't have enough food for the dogs. All the dogs from the Virginias would end up in the Carolinas.

It is still a mystery today how the hoboes and dogs survived going through the tunnels without suffocating. There were many poor families that lived beside the tracks. The hoboes would throw coal off the train to the families.

The majority of these hoboes were young men and just “good old boys” They were just looking for a better way of life. I never knew them causing any kind of trouble.”

PENNSYLVANIA

Max Sarnoff

Worked for MGM and rode freights home from Hollywood to PA

“Only someone who has had the experience of hopping a moving freight train and then sitting on the catwalk of a boxcar on a calm moonlight night singing The Sweetheart of Sigma Chi as the train crossed the southwestern states, could appreciate that fabulous sense of exhilaration.”

“The Smelters," a blast furnace identified as a landmark by the hobos near El Paso, TX. The Southern Pacific going East would have to cross a corner of the state near Juarez, Mexico before it crossed the Rio Grande into the El Paso RR yards. The hobos who didn’t want to be grabbed at night would use the Smelters lights in the sky as a signal to jump off the train before it crossed into the Mexico area.

One of the pleasant memories at that time were the Harvey Girls, the waitresses at the Harvey House Restaurants at the RR stations along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Line. When you appeared at the back door of the restaurant you could always get soup and a sandwich plus a cup of Java if you were willing to do some pearl diving.

Riding blind baggage… If you had nerve enough with the proper coaching by an old hand you might just make it without winding up in the “Clinker” This was done by sneaking into the “bellows” which was the corrugated closure on end of a passenger coach.

The blind baggage end was next to the coal car which stored the coal shoveled into the boiler. The engineer who usually saw you get on, pressing your body against the door of the baggage car, would say nothing until the train left the station.

Then you would have to get into the coal car and push the coal forward with your feet so the engineer did not have to stretch too much to shovel the coal into the boiler.

Yes, sir, you could get a fast trip from Chicago going west but were you loaded with coal dust!

PENNSYLVANIA

Oliver Levander

Fall of 1935, I was 18, friend Jim was 17, from Chesterton IND

Our purpose was to go to Florida and pick oranges for a living, which we did.

We were told that when we got to Texarkana the Sheriff picks you up and you get a chain gang for 60 days. They release you after 60 days and give you 60 cents. It was called the Penny Gang.

Then they took you to the next line and that sheriff would pick you up and get another 60 days and 60c

Hitched mostly, only rode freight home from Pine Bluffs.

PENNSYLVANIA

Richard S. Sheil

"In the western part of our country, from one year’s end to the next, the highways and freight trains are full of itinerant workers who are known as harvest followers.

These harvest followers manage to keep their bodies and souls together and their names off the relief rolls by wandering up and down and back and forth across the country, harvesting the nation’s crops.

In the early summer there is hay to be harvested in California and the Rocky Mountain states. Later on, there are corn and wheat in the Mid-West. Toward the end of summer and in the early fall there are sugar beets, and in the Pacific Northwest, hops, berries, fruits and more wheat. In the late fall, the far-famed Idaho potato must be dug.

Most harvest followers winter in the cotton fields of Texas and the Southwest; then in late winter and early Spring they drift into Southern California for the vegetables and citrus fruits, and back over their old route once more.

It is hard to understand these wanderers for they are so different from the people we know here in the East.

Many of them are refugees from the Dust Bowl. Unable, because of the droughts and dust storms of the past six or eight years to make a living on their farms, and unwilling to sacrifice what they call their self-respect by applying for relief or for work on the WPA, whole families have piled their few belongings into the family car or the farm truck and have set out to follow the harvest. Always they hope that somewhere, sometime, the men will find steady jobs and be able to settle down once more. Strangely enough, this occasionally happens.

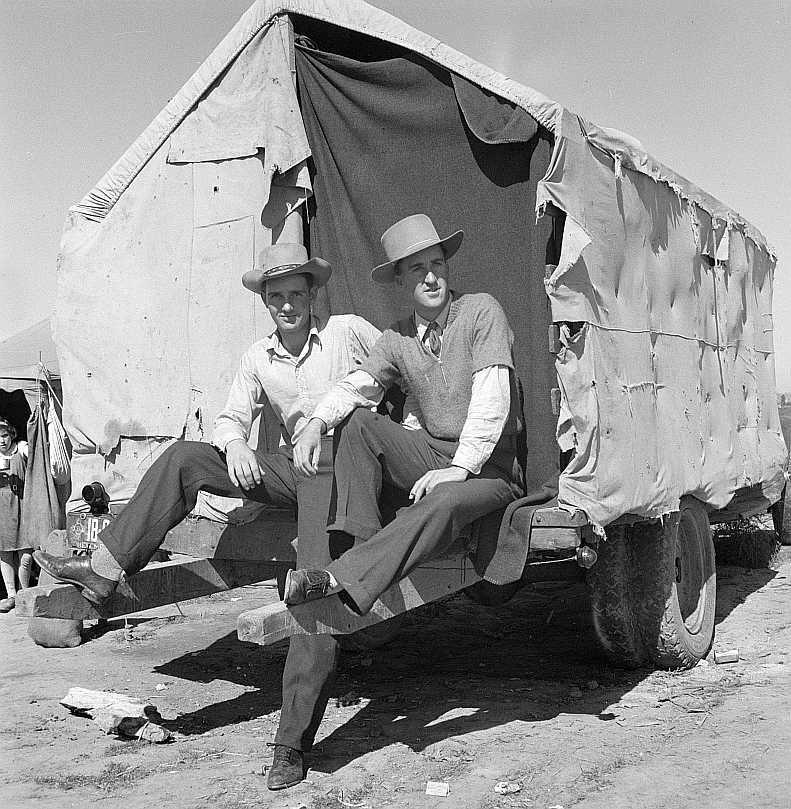

![Making lunch along the roadside near Henrietta [i.e., Henryetta,] Oklahoma. This is a migrant family en route to California Photo: Russell Lee Making lunch along the roadside near Henrietta [i.e., Henryetta,] Oklahoma. This is a migrant family en route to California Photo: Russell Lee](assets/images/rmakinglunch-611x692-38.jpg)

Most of the harvest followers are young men who have been unable to find work at home. Rather than "sponge" on their families or become objects of charity, they set out to work in the harvests, always hoping to run into a steady job somewhere.

The tragedy is that once these boys start rolling they find it hard to stop, and although they are good, hard workers they cannot stand the monotony of the day-in and day-out nature of regular employment when they finally do find it. This is hardly to be wondered at, since they no longer have home ties or close friends as an anchor.

A little more than a year ago I, like many others, gave up my humdrum job to go west. Two of us started out together from Philadelphia. Our first night away from home we spent in a Buffalo, N. Y., jail, having been arrested on a trespassing charge. This was rather serious, for both Mart and I carried hunting knives which is illegal in New York State.

Fortunately we convinced the railroad detective and the town police that we were not public enemies, for at the hearing the next day those little playthings were not mentioned. We were dismissed with a lecture and a suspended sentence. As a token of appreciation for the excellent treatment we received, Mart gave his knife to the desk sergeant and I gave mine to the railroad policeman who had made the arrest.

Though it is a deplorable state of affairs to have these men and boys roaming the country and risking their lives riding freight trains, they fit into an economic necessity, since without the migrant the crops could not be harvested.

It would not be so had if wages were sufficient to afford decent living quarters, adequate clothing and respectable means of traveling - but they are not. The men and boys live in hovels, eat the cheapest kind of food, and travel by freight trains or hitchhiking, both of which are against the laws of most states. For these offenses most of these wanderers have run afoul of the police at one time or another.

On this trip I learned a lot of tricks which I hope never to need again. One was learn to sleep on top of a moving freight car. That is one way to see the scenery. (I have heard chaps compare it to the upper deck of a Fifth Avenue bus.) We crossed Iowa sleeping in an empty stock car; it was the softest bed we had had for some time, but the aroma was pretty awful.

Nearing the Colorado Rockies we had to find the top of the freight car again. We passed through the Colorado Rockies in this manner. Before passing through the Moffatt Tunnel at the Continental Divide we climbed into one of the ice bunkers of a refrigerator` car or "reefer", to avoid being overcome by coal gas. This tunnel is, I believe, the longest in the country-over six miles long.

At Salt Lake City our train was welcomed by a delegation of policemen armed with rifles. They had little trouble convincing us that their city was hardly worthwhile bothering to see, so we caught the next train out. We were picked up by a railroad detective at La Grande, Oregon, who gave us the choice between buying tickets or being turned over to the civil authorities. We bought tickets and landed in Hood River, Oregon, in time for the fruit harvest.

We had a run of good luck at Hood River. The fruit ranch on which we worked is one of the best in the valley. The wages were five cents an hour higher than at most camps, and the living quarters, which consisted of small cabins furnished with beds, tables, benches, and cook stoves, were clean and comfortable. The cabins were lighted by electricity and firewood was furnished.

Camps such as the one described above are very unusual. In the Arizona and California cotton fields, for instance, the camps are so mean and dirty as to be utterly revolting. Lady Luck was not so kind to us after the Hood River episode.

Conditions were really bad in Arizona and even worse in California. After two months of cotton picking with our earnings averaging between four and five dollars per week, our savings became exhausted. At Buckeye, Arizona, we had a ragged tent to sleep under and the bare, hardpan Arizona soil to sleep on.

After bending double all day in the fields, the hard ground was just too much for our weary backs, so we (there were four of us traveling together at that time) rented a tourist cabin not far from the camp for two a half dollars a week. This extra expense however, destroyed our margin of profit, so after several weeks of struggling to break even, we gave it up. Steve and Corky returned to their home town in Arizona.

Lew and I went to Bakersfield, Cal., where for several weeks it looked as though we might get along. Our hopes were soon blasted when, in early December, the Bakersfield rains set in. We held on for several weeks, hoping for a break of some kind which would enable us to keep going, but day by day the rains became worse and our earnings smaller until we finally admitted that we were licked. We had had all the experience we wished to take. We decided to go home….

I learned self reliance, determination, capacity for hard work, optimism – all of which helped me in later life.

PENNSYLVANIA

Walter Drake

This was experience I wouldn’t trade even with the what learned in the Marine Corps. Taught me how to get along with others, how to improvise when necessary; how to depend upon myself; and that I could survive by my own efforts.

PENNSYLVANIA

William Bradley

16-18, 1936-1938

I had no home and was living by myself. I survived by stealing coal off the railroad and selling it 30-40 cents a hundred pound bag, or riding with the bootleg coal trucks to upstate Pennsylvania. A meal and a dollar to help load and unload.

Most memorable were the older men who had left their families and were looking for a job. I guess they thought of us young ones as their own children.

PENNSYLVANIA

William Csonder

Rode from about 13, born 1915 1928/29

Hungarian & Polish background.

I left home when I was around 13 years old. I left because our stepmother used to beat me, my older brother and 2 sisters. She never left me go out to play with the other kids in the area, especially to play football and baseball. She told me we couldn't afford to buy shoes and clothes. My dad, whom I loved, couldn't help himself and always accepted her side and would often beat us just to satisfy her.

I went door to door and asked for food. Sometime I would go the jail-houses and sleep there. Other times I slept in boxcars, cheap motels and when in New York, the subways, flophouses and missions. I begged for money which came easy because I was so young.

In Florida at Miami Beach I would beg people so I could get something to eat. One older couple gave me 25 cents and they were following me. They saw me go in a cafe. I sat at the counter and asked the waiter if he could spare me something to eat. He said yes. The couple who gave me the 25 cents called me out of the cafe. They then gave me another $2.00.

In San Francisco on Nob Hill (wealthy section) I would 'go on the street at night and beg for money. It was generally damp and drizzling and I would be wearing shorts and shirts. The people felt sorry for me and in half to three-quarters of an hour I could wind up with $2 or $3 (and I'd be shivering from the cold at night).

I would go to a cheap hotel, take a shower, and go to an all-night movie. This went on for about 3 or 4 months. I had to watch for the Black Maria (police car). They finally got wise to me so I had to leave San Francisco.

I saw many families traveling by riding the rails.

I traveled alone because every time I met a kid my age I would always lose them because they weren't fast enough to catch a freight train. I stayed away from hobo camps where they cooked in tin cans and waited for freight trains.

When they would all run to catch a freight train, the railroad dicks (detectives) would run after them and try to catch them. I always went on the opposite side by myself and went further ahead from where they were. Some of the well-known RR Dicks were Denver Bob, Two Gun Kelly, Texas Slim. Al1 carried 2 guns (Tough Guys!)

Met two brakemen who worked on the railroad. This happened at 2 different times. They wanted to adopt me. They had no children and told me they would send me to college. Took me to their homes. One time I had a boil on my heel. The family called a doctor and gave me a bath, clothes, socks, etc. Begged me to stay. I said no, for by this time I had wanderlust.

I would always beg for food and tell the people I could work for it. Very rarely would they ask me to work for it. So I had no disappointment.

I was really enjoying being a bum. I made ten round trips from California to New York in one year riding freight trains.

I got off a freight train near Jessup, Georgia. The train was getting water for its tanks. Ran across to a house and begged for food. Got the food and ran back to the trains.

I climbed up to the top of the boxcar and got a real surprise: There sat a RR Dick with a gun pointed at me.

I wound up in the County Brown Farm for three months. I think they sold your labor to some farmers or something like that. We chopped trees down and planted seeds here.

I saw there how they treated blacks. If they tried to loaf they would put their feet and hands in a stockade in a sitting position on a board that if you moved your body, the board would fall down and you would be hanging by your hands and feet.

We had a peek-hole to watch the guards who would beat them and then put them back to work!

There were many times my thoughts went home especially for my father.

Time I froze in winter: I lay in a hospital bed in Wyoming for a month and sometimes cried but vowed never to go home again. I missed my brothers and sisters (who also ran away from home.)

Other times I enjoyed it. Had a lot of good and bad experiences.

I got a job on the Southern Pacific Railroad, a water-boy's job - I carried water for the railroad workers who were laying track (gandy dancing.) Then about a year later, I stowed away on the Munson Steamship Co. passenger boat going to Brazil and Argentina. The butcher's helper got an infection on his leg and they had to take him off the ship in Bermuda and I took his place. I stayed on about 1-1/2 years.

I got a job to deliver soda in NYC on the corner soda stands. I went back to sea during WW2.