NEW JERSEY

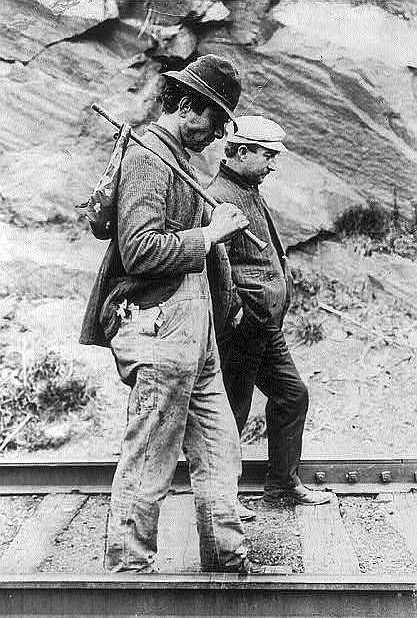

Jack Ingle

Catching a hotshot on a grade out of St. Louis one evening about 40 of us climbed up the ladders of the cars and were mostly sitting on the catwalk. A tunnel was just ahead and the warning straps were down about a block before the tunnel. A young guy didn’t know what the straps were that hit him, he didn’t duck and when we went into the tunnel he was blown away. He landed somewhere along the tracks.

NEW JERSEY

Omar McCoy

18-22, 1930 -1934

I was disenchanted with my home life. It fell to my lot to be my stepmother's lackey. My chores were household ones, cooking, cleaning, scrubbing, cleaning pots and pans. That was not the way to gain status with my peers who worked in the fields with horses and tractors.

What really drove me away was when I asked for fifty cents a week spending money and was told, “NO. You’re not worth fifty cents a week.”

I walked the tracks from Wilmington, Delaware to Alexandria Virginia, a distance of 105 miles on my first venture at the age of 16.

I can attest to the fact that the bulls used live ammo.

I think my days as a knight of the road was the best thing that ever happened to me. But I wouldn’t want to repeat the experience. It helped shape my character and instilled in me confidence that I could cope with whatever life had to offer. I started out as a teenager and came back a man.

There were many temptations along the way and it would have been easy to smoke, gamble, drink and steal. To be perfectly honest I did lift a quart of milk from a doorstep once.

NEW JERSEY

Robert Carroll

18-19, 1935

Rode rails after graduating from high school.

Several horrible images: When crossing the Ohio River from Ashland Kentucky I witnessed a homeless man being crushed by a moving train.

Once on a street corner in Louisville, Kentucky, I was reprimanded for talking to two young boys who were black.

While on the road I developed a philosophy of life, to say very little at all times, to keep people guessing.

I was especially aware of a prejudice against New Yorkers, and was careful about disclosing my identity to those whom I considered capable of bigotry.

NEW JERSEY

Watkins

1939:

“Don’t let any media kid you that the Depression was over by then.”

I was one of the lucky ones who got into the CCC.

Rattlers: fast freights

Slow Pokes

Drag Asses

Blue Velvet Band = Opium Pushers.

NEW MEXICO

Andres Gonzalez

New Mexican runaway kid

A.C. “Ace” Gonzales, b 1911

When he was 7 his father died; at 11 his mother died and he was sent with a small sister to live with his grandfather Antonio on a ranch in NM.

He had to work hard, in particular herding sheep. About a year later sheep died in a flood, so grandfather began following the harvest.

Andres got to Belen, New Mexico, south of Albuquerque, and decided to go east by way of Texas. He met up with some hoboes who taught him how to ride the rails. So he caught a train heading east.

He stopped in Vaughn, New Mexico, and was stopped by the sheriff. When he found out that Andres was not working, he offered him a job “lambing”. Andres said, “No Way.” The sheriff said, “Either lambing or jail!”

Andres chose jail. So that is where he spent the night. A trustee let him go early the next morning. He cut out straight for the rail yard.

Ultimately they landed in a huge hobo camp in Tempe, Arizona. This camp was a very notorious one. There was a woman named Winnie Ruth Judd, alias The Tiger Woman, living there at that time. Her reputation was from her killing two women in Phoenix, then shipping their bodies to Los Angeles, California. She was finally captured and sent to prison. They later sent her to an Arizona mental institution from which years later she escaped.

Worked four years at Boulder Dam.

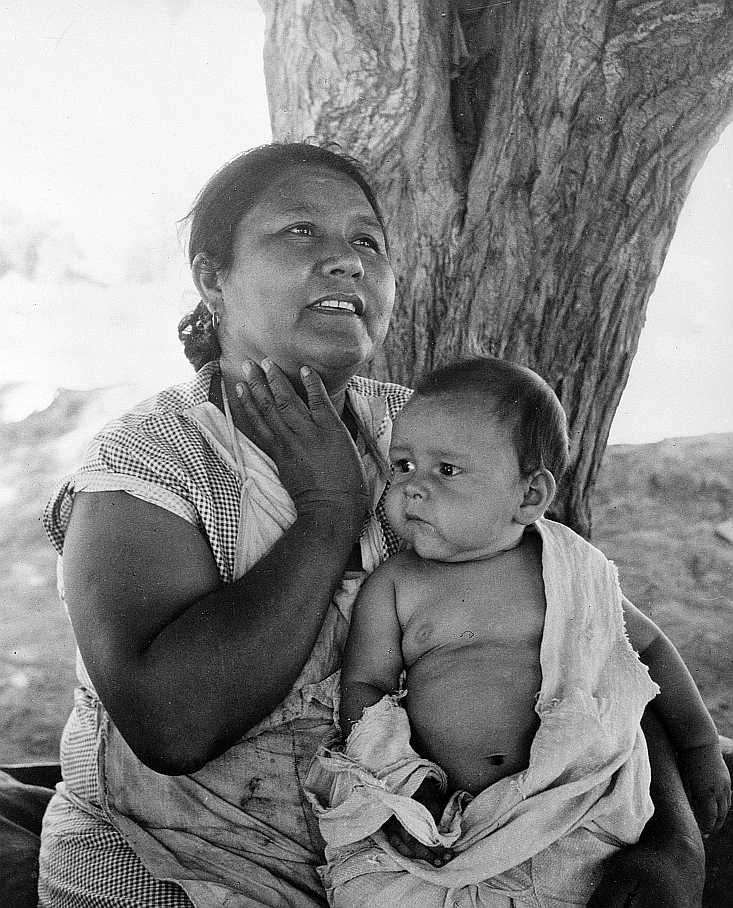

NEW MEXICO

Clydia Williams

b 1925?

I was about 7 years old when my mother gave me away to some relatives who were part Mexican-Indian and African-American.

The best years and times for me were 1930/32 riding the cattle cars.

Food was free. We ate in back of hotels and produce market places where people had stalls and threw away bad fruits and veggies.

Everybody was a hobo to the people who had homes and ran the towns.

The white kids got bothered by the truant officers and railroad detectives.... as runaways most were abandoned by their folks who couldn't feed them. They would show up again in some other town

When welfare came in 1935 or so, everybody took us in for the welfare. Then your relatives had place on the floor for you to sleep. That was worse than being on the road.

I was never lonely or unhappy until I had to live with family in run down, muddy, dirty cities.

My cousins went into CCC and so did some of older boys.

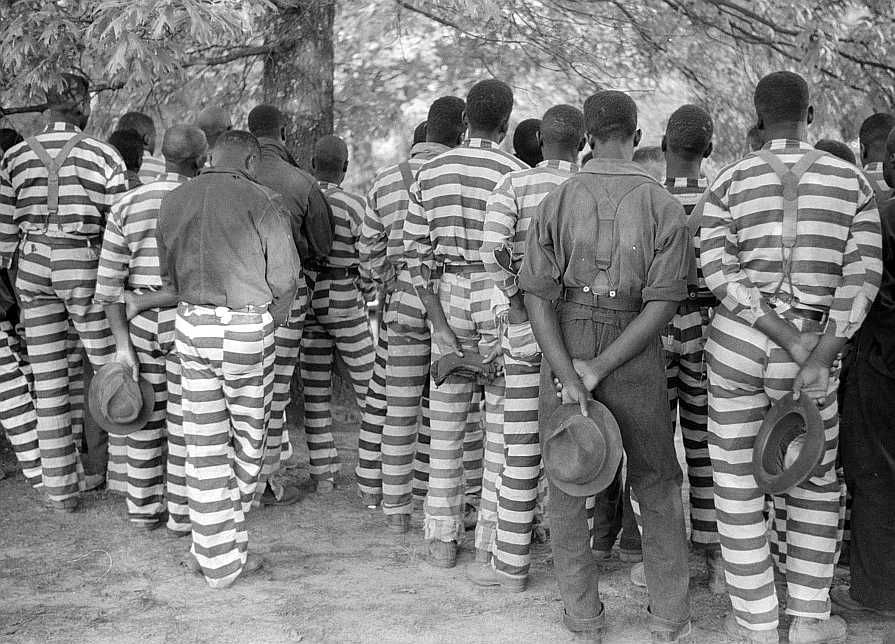

NEW MEXICO

Gus de Jong

17-19, 30-32

A lasting impression: A jungle along the railroad’s right of way and two railroad bulls hassling the hoboes. They were real brave with their revolvers and heavy clubs.

The smaller of the two hit a black person with the barrel of his gun breaking all his front teeth, upper and lowers, because he grinned when asked a question.

Railroad bulls and others like Sheriff’s deputies who sold the labor of those unfortunate enough to be caught in their nets. Georgia and other states going west.

It taught me to be patient, hate bullies, trust to no one, become a loner, self-sufficient, a realist, keep my own council.

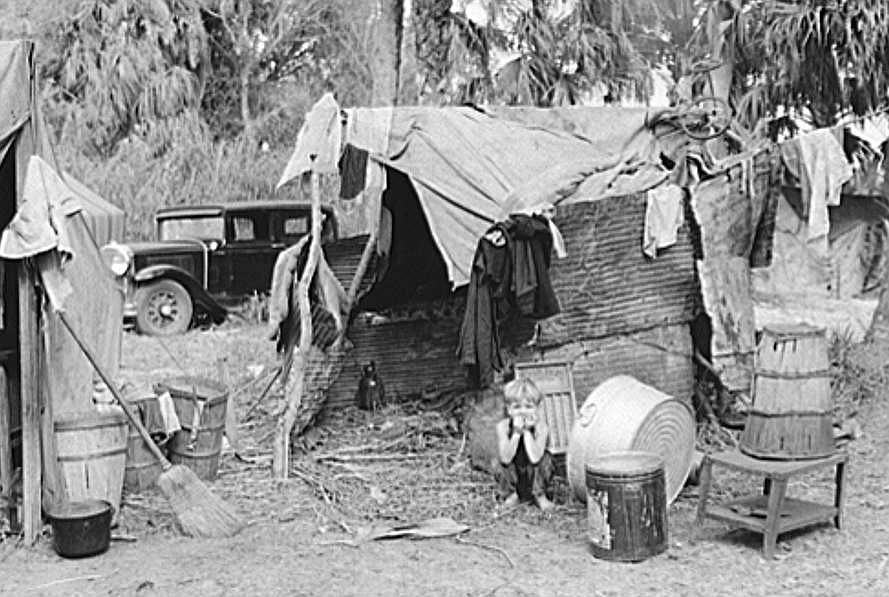

NEW MEXICO

Irving Stolet

1937, age 16

Runaways

Georgia, near Florida border: bulls took them off train…

"Kicked old black man everywhere till he was like an empty sack. I lay there petrified.

"Taken to jail... Old tobacco chewing judge….sentenced all blacks to the pea farm or time on the road. Then my turn came….

"The judge looked at me a couple of minutes, didnt say a word, then “get your ass out of that door.”

"Immediately picked up on crossing Florida border."

Lake Okeechobee, Pahokee The place was full of homeless men and women, living in a shack and tent city. It was a pitiful sight.

"Place was run by a mean woman who had a daughter about 14 who she rented out for sex at 50 cents. I caught a social disease, but that’s my fault – should have known better."

NEW MEXICO

Oscar Jones

Age 15

I was 11 when the Stock Market crashed in 1929 and at 15 it seemed to me that all I could remember was hard times.

"It's always better to ride at night. That way the railroad brakemen and bulls can't see the bo's so well."

En route to Dallas: "A middle-aged black man carrying a large suitcase. Just as he's jumping onto my car, his foot slips and he falls between the cars. The train groans to a halt. All seems so quiet. We've traveled half-a-mile since the man fell, but soon word arrives that he was decapitated. Mercifully, I think, he suffered no pain."

In jungle: "I'll show you a good time for a dollar," a woman said. She started crying. "50 cents," she pleaded

"There's a couple of whores in the boxcar ahead... In the car ahead of the whores is a woman just about to have a baby." -- The train stopped at Wichita Falls at 3 a.m. to take her off.

"I don't like to hit up bakeries," one bo said to another. "Too much pastries ain't good for a man." -- I've been trying to fathom that bo's philosophy ever since, but never could.

August 20: The peach picking season is now at its peak. My timing in coming here to Grand Junction was perfect. I didn't have a bit of trouble getting here, either. I caught a westbound Sante Fe out of Dodge and went straight through to Pueblo, Colorado, where I caught the D & RGW to Grand Junction.

I'm picking peaches (at 5 cents a box) near Palisades, which is a small town -- a shipping center -- about ten miles east of Grand Junction. I'm sleeping in the orchards at night, and my body is one huge mosquito bite.

Gone from home 175 days

"It's been a good year. I've sent over two-thirds of my earnings back home, enough to last us until next May when I go on the road again."

NEW MEXICO

Robert Allgood

There was the time when we pulled into Sheridan, WYO at 10.30 a.m. and the police were waiting for us. Their message: “There is a grocery store; over there is a water hydrant, cook up, eat up and catch the next one out.”

There were at least 250 men in that train, from many walks of life. Some were Nebraska farmers going to Washington to check out the feasibility of a farmer’s rehabilitation program that President Roosevelt had caused to be started there; many others like us, looking for any gainful kind of employment and one I’ll never forget:

He stood, addressing a power pole and looking neither right nor left, and gave an impassioned talk on the evils of “technocracy” which amounted to machines doing the work that previously had been done by the hands of men.

NEVADA

Arthur Lent

1929-1933, born 1908

“Adventure and financial burden were very minor reasons. By the time I was fifteen I became aware of no real father-son relationship. Our greatest falling out was because I challenged Dad about his radical Christian concepts. Morbid thoughts, which could have led to tragedy, was the main reason for my leaving.

I left with just the clothes on my back, a leather jacket, a small canteen and a small bag full of hardtack and dried fruit. Many times, it was several days before I was able to get a substantial amount of nourishment other than a bite of hardtack or a piece of my dried fruit.

There were several things over a period of months that left lasting impressions as I traveled in some of the Southern states. The terrible atrocities against the African-Americans, including beatings, killings, tar and feathering, and more by Sheriffs and other law enforcement officials.

Also, much superstition, acts performed, as part of religious functions. Many fraudulent practices against the less educated to con them out of their money.

Looking for work, I stopped at what appeared to be a small farm on the outskirts of a village near the Jersey line. There were two German brothers who were running the place. One a self-expressed preacher of the gospel. Both were hard-working men, who cared for anyone in need; including the blacks. I spent many days there. Every Sunday a score of people would gather and hear a Bible story in sermon style.

One Sunday, a neighbor who hated anyone who helped blacks suddenly appeared in an old Ford, jumped out of car, leveled a double barreled shot gun: He killed both brothers and wounded several people. He jumped back in the car and drove off.

Several times I was promised a certain amount on completion of a job. I was lucky to maybe receive a dollar or two cash or and a stale loaf of bread with the words, “Get going son, before I change my mind.”

There were many injuries. Some due to carelessness, but more from being pushed or thrown off or out of box car by the railroad bulls.

The worst that ever happened to me was a badly sprained leg and bodily bruises, when I slipped and fell from a moving train, as I was being chased along the catwalk by one of the railroad bulls, who if he caught me, probably would have beat me half to death.

NEVADA

Clifford St. Martin

16 through 23

1931 -1938

Parents separated. No relative wanted me around. Neither parent wanted anything to do with my two brothers or my sister.

“Begged on streets and at kitchen doors. Mostly slept in box cars or in jungles under loading packs. Worked on farms when available. Sometimes for food and board in winter. Also slept in jails, but didn’t care to because of lice and bedbugs. I would steal bread and milk from grocery steps in early morning hours. Sometimes slept in park or along road.

Kansas railyards, where so many people got off two or more trains at the same time that the rail yards were shut down until all the people got out of the yards.

When I woke in the morning I worried about something to eat; then I worried about where to go. Afternoon worry about something to eat; when it got dark it was time to worry about a place to lay down to sleep.

Friend Hank Beckner and I were Junkers always on the lookout for scrap copper, aluminum and brass. Copper was the best. It would bring about 3c a pound. We worked the power lines for dropped copper wire and the dumps wherever we went.

On a dump on Glendine, MT we found discarded sheets and pillowcases from a hospital. These were washed in the jungles and sold to car dealers for wiping rags.

At Alden MT we found so much copper we could not carry it all at once. We had several wash tubs full. The closest junk yard dealer was in Dillon MT 40 miles across the foothills.

So we drew straws to see who would fetch him. Hank walked all the way and came back in a truck with the dealer. I think we made about 40 dollars for our months of work. New shoes and overalls and a few good meals and sleep in a bed a couple of times and we were broke again.

NEVADA

Eugene Boyer

1933 at 23

Traveling partners left him because weren’t satisfied with his jungle cooking.

NEVADA

Harlan J. Peter

I was about twelve years old when this funny old hobo came to our summer-kitchen door to ask for a hand-out. He sang a little ditty while waiting, something about the lemonade springs in the Rock Candy mountains. It sure struck a chord in me.

Edgar Rice Burrows had just taken me to darkest Africa to meet with Tarzan of the apes. And then we went to the red planet to meet with the Princess of Mars where she let me ride the six legged elephant.

The old bum went into raptures about an enchanted land far to the west over the mountains on the shores of the Pacific. A place called California.

When mother brought the sack of sandwiches, a “lump" he called it, he thanked her profusely and slowly limped across the yard. He paused at the gate and made me a parting promise. "Just sleep under a tree, in the morning throw up a rock or two, and down comes breakfast"

Years later I discovered. that dirty old bum had a bad habit; he lied to little kids.

I learned that irrigation sprinklers made it very messy to sleep in fruit orchards, and on cold winter nights smelly smudge pots were a lousy way to avoid freezing.

It was in Greensburg, Kansas that it happened. It was a raw windy Saturday night, and after the last local passenger train had passed through, the night constable locked up the depot.

Unknown to my traveling buddy and I, he left the window unlocked and slightly ajar. We crawled in, made sure there was enough coal in the pot-bellied stove and settled in for the night. Less than an hour later the law checked his trap, and in spite of our pleas, marched us off to jail.

All that Civil Liberty stuff was forty years into the future. If you were on the bum, you wound up in the can. The constable was smiling as he promised to turn us loose come Monday morning. "We just can't have you bums panhandling our church people in the morning."

It was a pleasant weekend. The lockup was a huge room in the Court House basement. Four cells held center stage. Along one wall was a Pullman kitchen complete with gas plate and refrigerator. The reason the place was well stocked with food was a permanent, very bitter prisoner. An alimony casualty, he swore he'd rot in jail before he gave her another cent.

We ate bacon and eggs, then I cooked hot cake a couple of times, but had to throw part of the batter away. My stomach couldn't stand the pressure of a11 that prosperity.

The shower was a crude concrete stall but the water was warm and I almost cried.

When I removed my shoes and checked my three ace in the hole - twenty dollar bills I found the ink on two of them faded. The package leaked. My shoes weren't all that water proof, maybe it was sweat; at any rate it took two weeks to have them certified at a later date.

It was beyond El Paso that I first encountered the Dollar Divisions. Between Lordsburg and Deming, I think it was.

The crew stopped the train well out in the desert and with drawn guns and ready clubs rousted the bums and assembled them well away from the right of way. The order was “Pay up or walk."

The Mexican illegals all had their money ready. The bums that couldn’t or wouldn’t pay up had quite a sprint to get back aboard.

The ice bunkers are a cozy little compartment in each end of the car. They are about three feet wide and their length runs the width of the car. The walls are a heavy mesh that allows cold air circulation and also accommodates ladder spaced holes to allow climbing in or out.

Hatch covers are in two pieces. An outer light weight wooden weather shield and a heavy, thick insulating plug. The vibration of the car when under way will cause the tapered inner plug to wedge tightly. Even were you seven feet tall and could reach it, the hatch plug will lock you in.

The average bum either leaves the hatch cover open all the way or swings the hinged steel ventilating bar in the opening under the tapered plug. Either way, when the long arm of the law walks the top of the drag, its a dead giveaway. There’s a hobo in the hole.

The trick is to close the plug on a couple of cigar sized rolls of newspaper or small sticks. Now the “Man” sees no hobo in the hole. In case you ever find yourself in an ice bunker with the lid closed, just grab the mesh on each side then swing upside down and kick the hatch open!

NEVADA

John T. Gojack

Age 16

Extracts from a biographical mss:

“Getting out of New Orleans was tough. The railroad detectives went to great lengths to keep hoboes off the trains. Tougher ones beat people off moving trains, and turned over to local police those caught in the railroad yards.

It took us more than a day to catch a freight out. A few miles out of the switching yards, our train took a siding to allow a fast manifest to pass. Two dicks went up and down the train clearing everyone off with their police sticks. We walked back to a hobo jungle to check with bums who knew this area.

"There's a line about ten miles north where you'd have a better chance to hop a ride," one told us. "Watch for very long and slow cattle trains moving east, hauling animals out of the Dust Bowl to the Southeast for green grazing land," an old-timer advised.

"Do those trains go to Florida?" I asked.

"Sure," one hobo answered, "they all go to Florida or southern Georgia, but you'll be sitting on a lot of sidings. They have to yield the right of way to all other trains."

We walked toward the line recommended by the jungle bums and slept another night on heavy grass in a ditch near the tracks. Up and walking at the crack of dawn, we talked of food and wondered if there would be a town where we were heading. When we reached the line with the slow cattle trains, we were two days with only a candy bar each for nourishment. Fortunately, water was available near the water tanks every time the train stopped for coal or water…

A freight train pulling in from the West made the decision for us. It was a long and slowly-crawling cattle train. We spotted an empty car and hopped on with ease. The train was going slow because it was rolling into a siding just ahead, in order to let a fast manifest go by on the main line. This was fortunate, as it gave us the chance to look for a really clean car. Our first choice looked all right as it approached, but, jumping on, we slipped into manure and, looking for a spot to sit down, our only choices were more manure. We stood!

The train was pulling many empties so it was not long before we found a first-class car, this time a box car which would be much warmer at night. Later we complimented ourselves for moving back on the train, instead of forward, to find a better car. As the engine pulled out of the siding, picking up speed, we noticed people jumping off the train up front.

"Those cops are beating people off with their clubs," I told Vic.

"With the train speeding, it's going to be too dangerous to jump off," warned Vic. When hopping off a train, it’s crucial to hit the ground running, or else you might spill and hurt yourself badly.

The railroad dicks were now three cars in front of us, beating people off. There was a creek or bayou running parallel to the outer track, and it looked dangerous to jump off there. We kept one eye on the dicks working our way and the other looking for clear ground to leave the train.

"The dicks are on the second car in front of us. Look ahead and you'll see the creek or bayou has veered off to the right," I pointed out. The ground was clear and we were sitting with our legs outside the car, ready to jump and run. We saw the dicks push off a young man who failed to land running.

"That's the guy who jumped on in front of us." He was a tall, skinny kid, not much older than Vic, who made a bad guess. He should have hung on in spite of the railroad cops or jumped into a roll. Trying to land on his feet, off a train going too fast, had to be trouble. He tumbled hard, smacking into a metal rail switch light, and was not moving when our car passed him. We both felt sick.

"The poor bastard," I said with pity.

"Yeah, what rotten luck," echoed Vic.

There was a worse one a few years back, when a friend and I were going through Montana looking for work out West,” I said. “We had no idea how cold it gets in the mountains. We spent one night in a reefer (a refrigerated car, loaded with blocks of ice in the end compartments to keep food from spoiling).”

“Going west, reefers are empty and a great place to keep warm, if not crossing the mountains in September. It was too cold to sleep, and my fingers and ears were becoming numb. The train was speeding back to California with empty cars. There was no way for us to get off without breaking our necks. We decided to climb up and down, jump up and down, and wrestle standing up, to keep from freezing.”

“With the corrugated metal frosted, it was painful to sit for a rest. The water at the bottom of the reefer froze and it felt like sitting on a bunch of cold ; ice picks. Sitting became impossible and standing for hours in one spot on a bouncing train seemed like torture. That was the most uncomfortable and miserable experience of my life.

Finally, after daybreak, at Helena the train pulled in for water and coal. We couldn’t get off fast enough.”

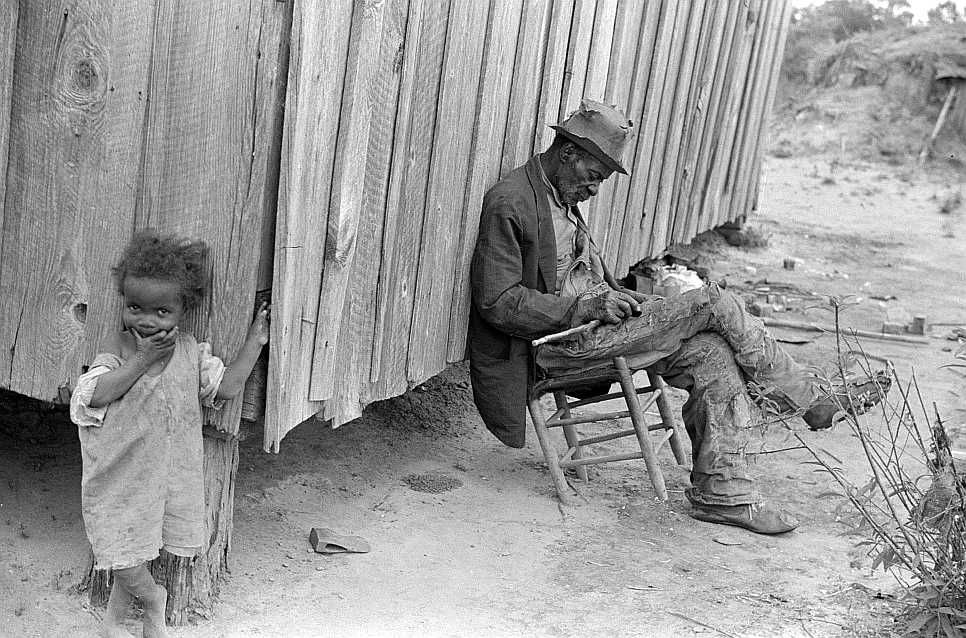

Sitting in front of a tiny cabin, with clapboard windows and no glass was a wrinkled old man with white hair. His rickety chair appeared ready to fall apart and he looked the same.

“Good morning, sir, may I buy some food from you.”

“We ain't got no food, boy," he cracked in a voice I could hardly hear.

"You must have something I can eat. I'll pay for it. I'm hungry and haven't had any food for over three days." Then, pressing desperately, "I'm terribly hungry

and I'll pay you well for any food," showing him some coins.

The old man pulled himself out of the chair and walked over to the cabin door. "Mandy, this 'yere white boy says he hungry. I'se told him we ain't got no food," he called out.

"Yeah, Josh, you right. All we's got is the pot likker from last night's supper."

"What's pot likker? Let me see it," I asked the woman in the darkened shack. In a minute a tiny, wrinkled, gray-haired lady stepped out. She looked even older than her husband and had trouble carrying a blackened kettle to show me. The bottom two or three inches were full of congealed remains of butter bean soup or stew. It did not look appetizing, but it smelled delicious.

"I'll take it, and please let me pay for it."

"We can't sell no food, son" said the old man. "Can he have it, Mandy?"

"Course, Josh, the boy looks neah starved and needs it more's we do." I wanted to kiss her toothless smile, both for her generosity and the loving way she expressed it.

My two new friends looked at each other, smiling and watching the white boy eat like a pig. I felt like a dog wolfing down jelled butter beans marinated in pot likker. I scraped every bit clean with a large spoon and would have put my head in the pot to lick it except for embarrassing my hosts. Almost finished, I remembered manners, lifting my head up for a smile and a quick thank you.

The friendly black couple was sitting near me and watching my every move, with grins on their faces. I liked the butter beans because they filled my stomach, and loved the old folks because they filled my heart. With no passing train in sight, I spent ten minutes or more with them.

"Thank you very much, Mandy and Josh, for sharing your food with me, and for inviting me into your home - it sure beats boxcars."

Having gotten more used to the light from the dim lantern in the cabin, I could see how poverty-stricken this fine old couple was, and marveled at how well they maintained their pride and dignity. It was a pleasure to slip two quarters under the butter bean kettle.

Hearing the fast train approach, I shook their hands and gave each a bear hug.

"I'll be back to see you some day, and we'll have a longer visit," I said, giving them both a peck on the cheek.

"The Lord bless you, son," said the sweet old lady. "You be careful, boy, and when you come back Mandy will fix you some real butter beans," promised the dignified old man. They both shook my hands again, and I left some tears on the cotton stubble as I ran back for my train.

My life has been full of wonderful people in many walks of life, who have enriched it tremendously. Mandy and Josh taught me a lot more than butter beans, now my favorite vegetable. They taught me courage, generosity, pride, dignity, and strength.

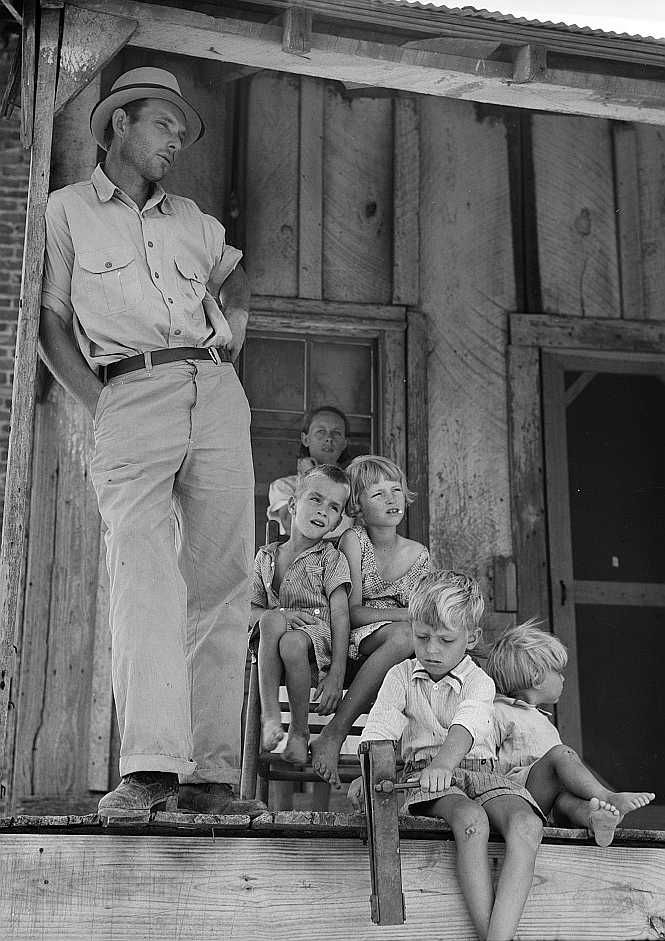

Outside Birmingham, Alabama we climbed into the one remaining empty car on a freight heading north. The empties, noted by an open door, all had people in them until we were at the end of the train. We felt lucky finding the last one, in the dusk and beyond the lights of the switching yard. Once inside, we heard voices in the far corner of the boxcar, one belonging to a woman. This was not unusual with hundreds of thousands of people and entire families on the road during the depression.

Getting accustomed to the dark, Vic whispered, "It’s a man and his wife, with three small kids.”

“Hello. Folks, sorry we had to barge in on your boxcar. All the others were full," I apologized.

"That's okay. We don't own the car. We're heading up to Louisville where we have folks and a chance to find work," said the man in a friendly voice.

"We'll bunk down at the other end of the car. You have some fine-looking kids there. Let us know if we can help in any way," I said.

"Thank you very much, and I hope the kids don't bother you with their playin' or cryin'.

The kids were quiet but about half through the night their mother woke us up with heavy moans, groans and at times a shriek of pain.

A nice-looking tall tall guy about 30 came over to our end of the boxcar. "I hope this doesn't keep you from sleepin', but mother's not far off from having another baby With three boys already, we hope this might be a girl."

"No, don't worry, we just came from hospital jobs in Houston and we're used to it. Just let us know if we can help," I said.

His wife was quiet off and on, and we managed to snatch a little more sleep. At first light, her cries were now steady and kept us up. Her husband called to us to come over.

"If you fellas wanna help, soon as the train stops, jump off and see if you can get us lots of clean sheets or towels and a bucket of hot water."

"We sure will."

Within minutes the train was slowing up, for a water stop as we spotted the tank in the morning light. We knocked on all the four houses and within minutes had plenty of clean sheets. linen brought along buckets of hot water from the engine. A new cry was added to the urgent voices and the steam off an idling train engine.

"She's a girl and she's fine," said the father.

The men slapped backs and a few of us cried.

Seeing families in a boxcar was not a rare sight. To have a baby on board just hours old was a great surprise and cause for concern. Citing our medical credentials with the seven months' work at the Houston hospital, we urged the parents to take the baby to a hospital in Nashville for a check-up.

"I appreciate your thinking of our baby's health, but our two youngest boys were delivered by a neighbor just learning to be a midwife, and you can see how healthy they are. I helped both those times and know as much as any midwife now," he said proudly.

Hardy people, these Americans, especially in difficult times.

NEVADA

Joseph Fowler

15-17, 1935-1937

In early spring traveling from Kansas City, Missouri across Montana after severe winter I saw hundreds of frozen cattle along the tracks.

I counted 40 antelope cross over a hill from the top of a train in Montana.

I was in Dumas TX working in the kitchen feeding workers in the Carbon Black Plants in the worst of the Dust Bowl. The dust was so bad we went out the windows to shovel the dust from in front of the doors. There was a corrugated steel cover built over the showers and rest rooms. We set the tables with plates, cups and glasses upside down to keep dust out. Dust pneumonia was common. Farm machinery was covered in a few days. The sun was a red blob in the sky. The wind blew constantly.

NEVADA

Mac Stine

Word got around that the place to stay was the Pueblo jail. It was quite chilly in the Rockies and I didn’t relish sleeping outside so I joined a crowd of a dozen others marching to the jail. True enough, the jail had a large room where you slept on the floor, the only redeeming feature was that it was warm.

Since the room was pitch dark, I had no idea how many were there, but my imagination told me more than a hundred snoring bodies were on the floor. I stumbled in over the bodies, found a space to lay down and in no way could I go to sleep.

Two policemen were somewhere in the hall practicing on a guitar and a mandolin with constant talk and occasional singing; the floor was hard; I was sure someone was going to steal my suitcase; fleas began to crawl on me and worst of all, it was HOT.

I decided to suffer somewhere else so I stumbled out of the place out into the cold evening again. It was probably around midnight as I headed toward the railroad yards again. I found an empty box car and spent the rest of the shivering night huddled in a corner.

TUESDAY, June 20, 1933

I was up quite-early having spent a sleepless night. I had coffee and donuts - 10 cents at a diner nearby. At 7:30 a.m., I caught a freight out of Pueblo and really felt I was on my way east again. It was a fast freight and didn't stop until La Junta. Why did it stop? I was told the day before that all red balls (fast freights) moved through La Junta without stopping. I soon found out.

A contingency of yard police and local police rounded up all vagrants on the train and unceremoniously herded us out of town to the highway heading east. With that mob on the road, I knew there was no way of hitching a ride. I marched to the head of the crowd and on ahead, where I was lucky to get a ride to Las Animas, 16 miles east of La Junta.

At Las Animas I was lucky to catch a ride on a local freight to Syracuse, Kansas about 100 miles east of Las Animas. Syracuse was a fairly large railroad center and was making up a Red Ball headed east. I spent 25c for supper in Syracuse. We left in the early evening passing through Dodge City and arriving in Newton, Kansas around 1 p.m. the next day.

WEDNESDAY, June 21, 1933

This was another low point in my morale on the trip. At Newton, the yard police met us about three miles out of town, herded us into a group, demanded identification from each of us and threatened to shoot us if we attempted to run away from the group. We were herded onto a road heading into the city and told to march.

The two yard police had a car and constantly made us move faster by bumping the laggers. If I ever hated anyone, it was the S.O.B. who was herding us. We marched to the Newton train station where were lined up again and those without identification were arrested as vagrants and the rest of us stood around for several hours wondering what would become of us. All of us agreed that the yard policeman (bull) who herded us into town was one of the meanest we would ever meet. He would not let us get anything to eat, only drinks of water and the use of the toilet.

Some time later the local police arrived and to their enjoyment gave us the impression we were going to be put on the prison farm to pick peas. “OK get going, you’re marching to the farm.” What sadistic enjoyment they had.

So about a dozen of us were marched down the highway with the police in a squad car behind us. We passed the city limits and about a mile beyond the police car turned and headed back to town leaving us puzzled as to the next step. . .

The first thing you must do after arriving in St. Louis is cross the Mississippi River to East St. Louis, Illinois, where the freights are made up for trips east.

It took most of the day to get information on a Pennsylvania Railroad freight that was leaving in the early evening. My notes show that I spent 5 cents - coke; 10 cents - car fare; 25 cents- breakfast and 15 cents lunch in St. Louis.

The train was made up of fruit cars from California and I happened to select a car where the ice compartment had not been re-iced, a car full of lemons. That I could take.

As near as I could determine, I was the only vagrant aboard and being a fruit train, I surmised we were going to move rapidly toward the eastern market. The ice compartment that was to be my home for several days is on the end of an insulated box car. It is the width of the car and about 3 feet deep into the car cavity. Instead of a solid wall between the end compartment and the fruit, a divider similar to a chain link fence is used. An annoying item was the floor which appeared to be made out of corrugated roofing. After spending time laying on the floor, your back felt like a washboard.

The only light you have in the interior is what comes through the overhead hatches - hinged doors to provide access for ice and us unscheduled passengers. A ladder is provided on one wall for access. In rainy weather you must close one of the two hatches and leave the other one slightly ajar. Since the hatches can be locked from the outside only, you must devise a scheme to prevent being trapped inside without any way of exiting. I had picked up a piece of board that extended across the opening that would prevent closing without removing same, which would surely allow time for me to yell. However no incidents occurred.

The train left East St. Louis around 7:30 p.m. After an overnight run, we reached Indianapolis around 6 a.m. the next morning, I had slept all the way, lulled by the smell of lemons.

SATURDAY, June 24, 1933

I got off the train, got a drink of water and re-boarded my private compartment. After about 30 minutes, we were on the way again in which time the changed crews and locomotive. That afternoon we arrived in Columbus, Ohio.

Shortly after I arrived, we were inundated with a heavy thundershower with lightening flashes about 30 seconds apart. I huddled under a railroad car; not finding any open box cars available. Following the storm, I went to a nearby grocery and bought a 25 cents grocery dinner, after which I returned to my compartment. Around 9 p.m. we were moving again and arrived in Pittsburgh the next morning.

SUNDAY, June 25, 1933

A friendly brakeman had told me that the train would be breaking up at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: the end of the line. As I was riding during the day, I had got used to the luxury of a private compartment and sorta dreaded what would be ahead. The train arrived at Harrisburg around 4 p.m.

Upon inquiring about freight trains heading for New York, I was told that the normal terminus was Newark, New Jersey. A coal train was scheduled to leave in several hours and thus beggars not being choosers - I choose that as my final leg of train riding.

Riding in a coal car on the trip to Newark isn’t the exact example of elegance. If you had your choice of car a coal car rated very low. You back yourself against the end of the car – sitting on lumpy chunks of coal with your feet elevated as the pile was elevated toward the center of the car. All of this is with the train standing still.

As the train jounced along, the lumps didn’t get any softer and naturally the cars had no springs. We left Harrisburg at about 8 p.m. and arrived in Newark at 5 a.m. completely permeated with coal dust. There was about 20 of us in the car and from the looks of others, we were a complete mess.