On December 2, 1979, James Michener and I lunched at Longfellows on the waterfront at St. Michaels, three weeks before our work together ended. On our daily walks I often spoke of ideas for novels: Brazil (As a first step, Michener urged me to read Gilberto Freyre's Masters and Slaves, which I did long before sitting down with Professor Freyre in Recife:) How Peace Came to Europe (the displaced and the dispossessed after World War II;) and a book about the blacks of South Africa from 1600 to the present, a counterpart to the story of the Afrikaner Van Doorns.

At lunch, our table talk turned to those ideas. - Interrupted by "Jim, the food critic," rating the local crab cakes, a task he took very seriously, his highest rank a "9-plus" going to a couple met during his Chesapeake days; when we dined with the them I saw Jim's written accolade in a silver frame on their sideboard! - I later summed up what Jim said at Longfellows:

Every excerpt, every page you have written for my book these past weeks shows that you are a writer with a superb use of the English language, a remarkable vocabulary and a very special turn of phrase. You are as ready to write your book on the black people of South Africa as you will ever be. If you waited five, eight, ten years you'd be no better. Get started tomorrow.

I never normally go this far, but I would say that you are virtually guaranteed acceptance. Work up the synopsis and write two chapters - they have to be damn good mind you - and you'll definitely get an advance on them. I will give you any help you need in getting it placed with a publisher. I believe this book - and others you've mentioned like How Peace Came - will be a great success.

I note that you wrote to me on the same day that you wrote Thompson, (Ed Thompson, editor-in-chief of the Digest ) so I judge that between the two letters I have a full picture of your thinking. It's quite gallant, and the most important thing for me to say is that I stand by all I said in your reconstructed note of our December 2 luncheon at Longfellows. I think this is important because you will need constant assurance in the months ahead.

You unquestionably have the talent to write almost anything you direct your attention to. You are a great researcher, as your copious notes prior to our work sessions together indicated. And you know how to put words together most skillfully as your work on the manuscript proved. With such talents you stand a remarkably good chance in whatever you try. You have also, from what I gleaned in our conversations on the long walks, an acute sense of timeliness in subject matter. That's a rare combination, the most promising I've met with in years of talking with would-be writers.

c/o James A. Michener, St Michaels, December 2, 1979

My dearest Jan,

My last letter, written in the fire of anger, aptly caught the way I felt that night. I got to bed at one and stayed awake in smoke-filled contemplation till four-thirty, even later. Two hours' sleep, a shake-awake shower and I marshaled those battalions of tormented musings. To quote them:

After eighteen months of work on Michener's manuscript, I am told that "in some special cases, if a book is successful, I tell my researcher to go down to the travel agency and pick up a ticket to Europe. In one very special case, I gave a wife a ticket as well." This was offered after I raised questions about a dedication note. It also came at 11 p.m. after a fifteen hour workday, and I reacted with a fumbling, "yes?" Perhaps also a "really?" It was also noted that I should consider asking the Digest for "overtime" compensation.'

....Now, dear departed friend, Aunt Kathy (Note: Katharine Drake, a veteran Digest writer who took me under her wing) once told me that to be a good wunderkind you sometimes have to compromise, you have to keep the voice low, mind in neutral, heart in reserve, and swallow deeply. Advice, Aunt Kathy, which stood me in good stead on many an occasion particularly in the 'gathering-clout' days. But, there also comes a time when you say: No further! That day had arrived.

I walked slowly to the house, quietly, calmly, more calmly than ever I'd been in such a situation. I had decided that I wasn't writing another word, suggesting another change, exchanging another view, until I'd made the rage within absolutely, unmistakably clear. So: "Before we go any further, Jim, there are a number of things I'd like to say."

I still remember every word. It was very important to me because that morning I finally staked my claim to being accepted as a writer, as an intelligent, independent 'being', as Errol L. Uys. 'Liberation' from a lot of inhibiting things still trying to dog my progress. I won. In my own estimation of 'me', and in Jim Michener's eyes. I recommend the experience to anyone who wants to stand on his/her own feet, and is really sincere about making something out of this life, in the biblical 'talents' sense or otherwise.

It began with my saying that I had great respect for him as a person, as a writer and, I believed, a friend and mentor. I was very conscious of the odd relationship I enjoyed apropos my position as a Digest employee and that this might preclude -- or suggest 'cooling' of -- the sort of decision I'd come to. However, there's, a time when, dammit, you have to dig your heels in and say, This is where it stops! This is where my quiet, accepting manner goes on the shelf.

What I had to say was in no way to be seen as an 'appeal' for a bonus, for money etc. He had probably assessed my financial 'bones-of-ass' situation, but that was of little consequence for I had a lot more going for me as I have no doubt, none whatsoever, that my working with him was not the luck of the draw, but part of a 'greater plan' and just as he'd stopped 'wasting time' in his latter 30's so had I ...

I wanted to make it clear that while Bateman, whom he appeared to think had done a major portion of the work, certainly did assist greatly; Philip had a) been paid a handsome reward in fees and expenses by any standards and that b) there was no doubt in my mind -- every scrap of paper in that room bore me out -- that for every hour Bateman put in on the project, I put in ten.

I was not overestimating my talents in relation to those of JAM, I said, but neither was I prepared to underestimate them. Since I had started working on this project, especially the final editing stage, I had repeatedly heard the remark that 'Well, yes, but that's only for a South African audience.' Frankly, I said, if that's how he felt, and I did not believe it was true, then I was deeply disappointed for I had taken The Source , Hawaii , Centennial etc. as 'accurate' and I had believed, as his readers did, that he went to painstaking lengths to ensure that accuracy.

I did not accept that at any stage James A. Michener had intended a 'yarn' or 'pot-boiler' on Soth Africa but a truly great novel. I wasn't even going to attempt an elaboration of the many areas, chapter by chapter, line by line, that required changes, not merely 'Southafricanizing' but critical in error/misconception etc. ("Struth, it came out like this, word by word. Sounds strong recounting it, but I was damned if I was going to keep quiet. I've put too much into this.)

Then, a shift to the 'free trip': Jim, I said, I was Editor-in-Chief of SARD. (South African Reader's Digest ). Through that, and through my own initiative I've been round the world, traipsed through Europe, South America with my family etc. I was not soundin' off like an ungrateful slob, but equally I did not expect to be treated like an undergraduate student "assisting the author with his research..." That was exactly how his "offer" had come across to me. I just wasn't impressed with his a) walking down the road with me the previous p.m. saying this book is going to be read by 20 million people and, b) now saying that 'perhaps', 'if,' 'maybe' it sells, I 'might' 'maybe' 'perhaps' be offered this Europe bonanza. Sorry, Jim, I know what I am worth in this project and that, the way I see it, was not worthy of you nor respectful of the relationship we enjoy.

I said that he should be aware that no editor asked his employer for 'overtime'. I was sure Albert Erskine at Random House didn't do it, and I had no intention of doing, it either. The effort I have put in, the enthusiasm I have for turning out at 8 a.m. each morning and working till 11 p.m. is not because of the Digest but because of the way I am. If I do a job, I do my best. I work damn hard, and if it's acknowledged, that's great. If it's not, that's not so great but I give myself a pat on the back and say, 'One step nearer, Uys.'

I wound up by saying how much I truly valued working with him, how much to heart I took his words that I should make the most out of that linkage. I would. He could bet on it.

In short, I had finally told myself that I was a fabulous writer. Sure, there are rough edges to iron out, a world of knowledge (not on writing) still to be acquired but I'm a writer .... Henceforth, love of mine, nobody tramps on my pathway in that direction! Not even, dear Jim.

Jim listened very quietly to all this, and his response was quiet. He didn't disagree with anything I said. He said he valued my work more than anyone who'd ever assisted him. I was, unqualifiedly, the best. He appreciated. the difficulty I faced in bargaining power as a Digest employee. Admitted that he was wrong in the 'South African-izing' aspect. Nothing I had said was lost on him, that he appreciated my coming out with it. That he believed a person was entitled to a fair share. That was it. In sum, for he had a lot more to say.

I am satisfied. He knows exactly how I feel about this project and my contribution toward it. Since then, our relationship has warmed considerably. No longer does he look at me as a Digest employee, but as Errol L. Uys and that makes a helluva difference. (Mari, knowing nothing of this -- so far as I can determine -- raised her glass to me the other night and says that never has anyone from the Digest been as hardworking, diligent etc. as me. She is, by the way, feeding me as if the great famine was around the corner.)

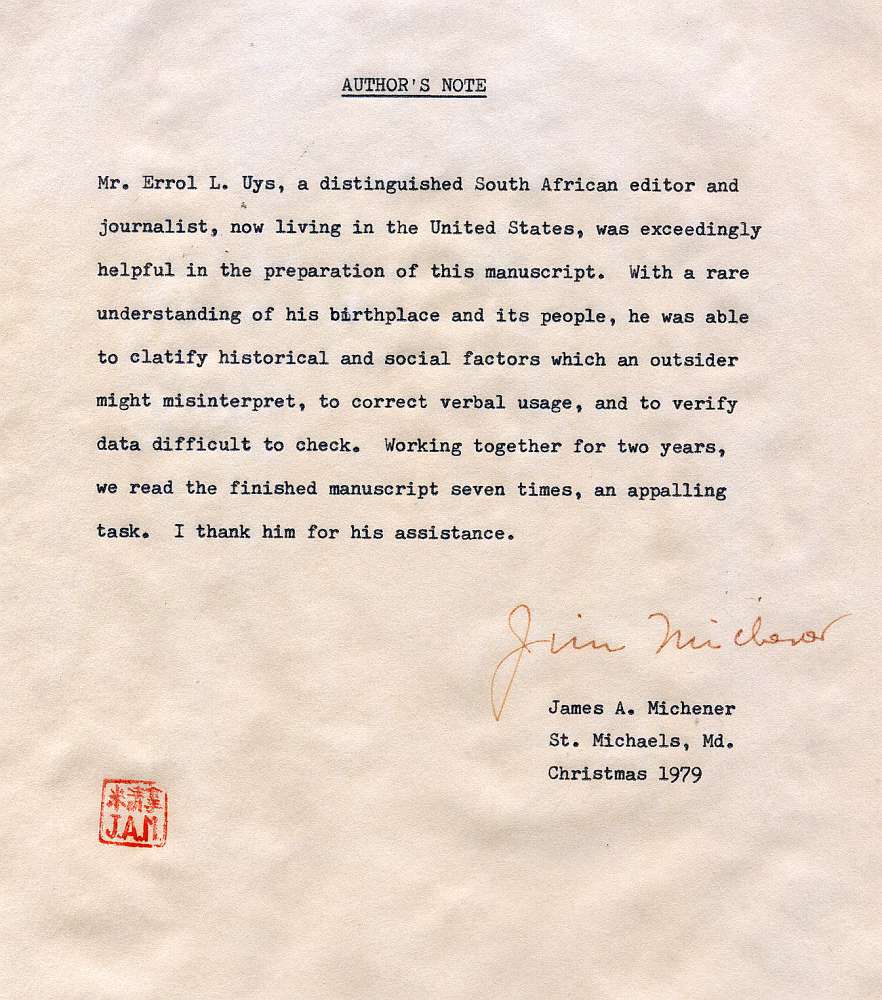

The upshot of my showdown came with Jim asking the Digest to pay me a $5,000 bonus. He scrapped the dedication and added an author's note to the novel suggesting that my contribution was after the fact of the novel's creation and restricted to clarifying historical and social factors, correcting verbal usage and verifying difficult data...

On December 21, 1979, I wrapped up my work on The Covenant and bade Jim farewell heading home for Christmas. A parting with a wry Dickensian twist, for Jim presented me with a wild goose from Mari's larder, for my family's festive table. The bird turned out to be inedible, riddled from stem to stern with lead shot.

I was back at my desk at the Reader's Digest in February 1980, when out of the blue I got a broadside in the shape of what I've come to call "the Avenick letter."

Jim had previously told me that Joseph Avenick, who assisted him with Sports in America, was going round saying that he'd ghost-written the book. Michener had sought to dismiss Avenick by suggesting he was lost in a miasma of letter writing to the President, the Pope, Ted Kennedy et al.

In his missive to me, Michener threatened me with the same woeful fate should I claim to have done more than vet his manuscript.

St Michaels, Maryland, 2 February 1980

Dear Errol,

Joyous omen for Errol Uys! The man who did the vetting of Chesapeake, and who has written that splendid manuscript on the slave-philosopher Frederick Douglass without any chance of getting it published, learned last week that three major houses wanted to take it, and the choice will be between two of our most prestigious, Yale and Johns Hopkins. I think I'm happier than he isOminous omen for Errol Uys! The disorganized young man who did the vetting of the sports book, and who has told several newspapers that he ghostwrote my novels, has fallen into even worse miasmas, as the attached letter shows. As I told you when we discussed the problem, whenever a writer sends carbons to the President, the Pope, Senator Kennedy and me there's serious lack of focus, but such letters come trailing in month after month.

So which precedent applies in the Uys case I can't decipher, but they are certainly running loose and I'll invite you to choose the one which attracts you most.

Albert (Erskine) and I start our work on February 15 but he startled me the other day by advising me , 'throughout the manuscript you misspell Karroo. It has two r's.' And all the maps he had showed it with two, except that all the maps I had showed it with one! We'll probably use two.(*Note: from Khoikhoi karo, karro hard, dry, both spellings are correct, though Karoo is in common usage.)

What I chose to do, of course, was leave the Digest at the end of 1980 and devote myself to my writing. My historical novel, Brazil, was five years in the making, with Simon & Schuster giving me a $45,000 advance, my only income over this period. On occasion, I asked Jim for financial help, which he never refused; for his support in seeing Brazil to completion, I remain grateful.

Prior to publication in November-December 1980, The Covenant was banned in South Africa. This judgment was largely based not on the novel itself, but two condensations published in Reader's Digest focusing on contemporary apartheid issues. A slew of Afrikaner critics weighed in against the novel, W. A. De Klerk calling it "pretentious literary trash," not worth a banning.

Jim and I could take heart though from another reader who saw the book in a different light: "White South Africa is a society corrupted by racism," said Alan Paton, author of Cry, the Beloved Country . "Michener sometimes exaggerates and over dramatizes, but he is exaggerating the truth...I cannot call this anything but an extraordinary book."

There was a special bond between Michener and I that went beyond the words we wrote. Neither of us knew our birth parents and had grown up in genteel poverty. At nine, Jim was scouring the Doylestown woods for chestnuts to sell to neighbors; my first enterprise was selling peaches in the street outside our house. From the age of eleven until he was a young man Jim worked at many jobs from paper carrier to ticket taker at Willow Grove amusement park outside Philadelphia.

I was eleven when I started my mini-career as salesman in a Johannesburg toy store and pitchman at the Rand Easter Show. As teenagers, Jim and I both hit the road and stuck out our thumbs, hitchhiking thousands of miles and beginning the life journeys that would see us walking together on a road in Maryland. Neither of us would publish our first books before we were forty.

Our collaboration on The Covenant was unique, different from any other assistance Jim had in producing his works of fiction. I remember my excitement in coming to work with America's best-loved writer, sharing my passion for storytelling and my hunger to let the world know the story of South Africa. I see us wrestling with all those grand ideas on our mighty journey through history, Michener and the boy who wrote Revenge.

I hear laughter as we swap ideas for the red-haired terror Rooi Valck and Mal Adriaan, Crazy Adriaan, who found the lake called Freedom. I feel again the sorrow we knew at the death of Old Bloke dying like a dog in the road when a WHITES-ONLY ambulance won't pick him up. I see Van Doorns, Saltwoods, and Nxumalos, moving forward with The Covenant , character-by-character, scene-by-scene, until the day when their story was told. I see it all as clearly as if we were back in the cottage beside Broad Creek on Chesapeake Bay.

Excerpt from Michener - A Writer's Journey by Stephen J. May, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 2005

"Uys returned to St. Michaels to complete the final revision phase between September 8 and December 21, 1979. Often Uys handed Michener whole prose passages running several pages for Jim to scan and use in the narrative. Jim would alter them slightly, reword sentences, or copy them verbatim into the text. Such behavior at least confirmed in the back of Uys's mind that Michener would offer him a coauthorship or part of the royalties. Neither was forthcoming. Working fifteen-hour days, plodding line by line, the two men went through the manuscript. By the middle of December their work almost complete, Uys worried that Michener might not fully acknowledge his contributions. This became apparent when Michener showed Uys his planned "Author's Note," that would be placed at the beginning of the book, indicating in part that Uys "had read the manuscript seven times." The note gave the impression that Uys's contributions only occured during the final drafting of the manuscript as copyeditor.

"Uys's fury slowly simmered. He was raised in a tradition where one's work had to be dutifully honored, and he felt the need to confront Michener about this obvious plagiarism. Toward the end of their time together, Uys asked Michener about their collaboration. Jim offered Uys help in getting his next book published; at one point he offered him a trip to Europe for his time and contributions. Uys brushed off these feeble gestures. He probably would have had much better bargaining power had he been a more established writer and not tied to the Reader's Digest. In the end, Michener offered Uys very little that had to do with The Covenant, which left Uys disheartened and resentful. As a parting gesture of goodwill, Michener gave Uys a Chrstmas goose. "It was a wry Dickensian twist," remarked Uys. "The bird, loaded with shot from end to end, was inedible."

Ultimately, Jim asked Reader's Digest to pay Uys a $5,000 bonus for his contributions, a meager sum considering that rights to the Literary Guild edition fetched $1.5 million several months later and the eventual hardcover and paperback sales exceeded $2 million. With The Covenant, Michener committed a scarlet literary crime and used his celebrated status in publishing to get away with it."