One of the first drafts Michener sent me for research was a comparison of the continents and their relationship to the various settler groups who landed there:

As the Dutchmen from the Cape took their first hesitant steps eastward and northward into the great continent at whose edge they perched, it would be profitable to inspect what kind of land they had inherited and to realize how limited and hostile it was. Settlement could not be extended to the northwest, for there lay the Namibian Desert, a cruel boundary, and it would be difficult to penetrate the vast region of the northeast, because this contained the Kalahari, less formidable than the Namibian, but also a desert. To the east and northeast ran the towering Drakensberg Mountains, many of the peaks over ten thousand feet high, protected by precipitous valleys almost impassable.

But the wasteland of Australia, the Rocky Mountains of North America, and the blizzard weather of Siberia proved no natural impediment could stop men from moving outward if they were determined to go. And in time the adventurous Cape Dutch would conquer their Kalahari and Drakensberg. What really set limits to their population and their economic growth was not the formidable land to the north but the missing land to the south.

Of all the major continents, Africa is the one that hugs closest to the equator, the only one that does not have a substantial area in the temperate zone where farming can flourish, or industry thrive, or great cities be established. Look at a map of Africa, and compare it with South America which shares the same oceans, and see how truncated the former is! South America reaches south to the fifty-sixth parallel of latitude; Africa cuts short at the thirty-fifth, which means that the former extends some 1,400 miles farther into temperate climates than the latter.

The discrepancy becomes more meaningful when one compares the brevity of South Africa with the expansiveness of Asia, Europe and North America, for then the real disadvantages under which the Cape Dutch suffered become apparent. If these continents had been cut off at the thirty-fifth parallel north, Asia would have lost Kyoto, Tokyo, Peking, Tientsin, Tehran and Ankara. All Europe would be lost with its cities, its factories, its farms and its ennobling institutions. In North America there would be no Canada and all of the United States would be cut off down to a line running south of Chattanooga, Memphis, Oklahoma City, Amarillo and Albuquerque. Those cities and all places to the north like San Francisco, St. Louis, Detroit, Washington and Boston would be eliminated.

If the northern continents were as truncated as South Africa, their civilization would be limited to what Canton, Delhi, Jerusalem, Dallas, Mexico City and Los Angeles could provide. The great farming areas of China, Russia, France and Canada would be lost, as would the industrial centers like Tokyo-Yokohama, Peking, Moscow-Leningrad, Pittsburgh and Detroit. World civilization would be immeasurably poorer: cathedrals would not have been built, plays not written and poems not composed.

What this means is that the Dutch who occupied the Cape found themselves in possession of one of the world's deprived areas ; the lush farmlands which ought to have stood to the south did not exist; rivers comparable to the Yangtze, the Rhine and the Mississippi did not flow; and the wealth which had been created in the vast temperate zones of the other continents could not be duplicated in South Africa, no matter how diligently the Dutchmen worked.

It was therefore doubly to their credit that they accomplished what they did. Working always with a limited natural endowment they achieved miracles; they did not surrender to adversity and limitation but did transform these deficiencies into assets is. It is not admissible to contrast what the Dutch accomplished economically in South Africa with what English settlers achieved in more propitious North America; the latter had all the advantages; the former had few because their continent had treated them shabbily. - James Michener, The Covenant, First draft

Pleasantville, New York, November 21, 1978

Dear Jim,

Herewith another batch of comments, thoughts, notes etc. on the theme "The Promised Land - Limited or Horizonless?" It also looks at the question of the vanishing wildlife and the changes that came to the wilderness with the advent of the plough, the gun, barbed wireOf course, viewed in the broad context your comparisons with other continents are fine: I have this nagging doubt about some of the specific statements that emerge, the limited natural endowment etc. The Namib, the Kalahari were indeed there. Yet, far greater, was the extent of the Living Veld - the Eden so many early travelers speak of.

So, I offer these notes from numerous sources for your consideration.

In a broad "sub-continental" sense, the "limits of expansion" comparison is acceptable. I'm certain you've already considered many of the comments that follow: They're of a qualifying rather than definitive revision nature. (Certainly, I begin to grasp the broader Michener vision of things and am cautious about dismantling what is essentially an enlightened, fresh perspective.)

But what worried me on successive readings of the section were some of the descriptions of the land the Dutchmen inherited: Limited and hostile; one of the world's deprived areas; the wealth which had been created in the vast temperate zones of the continents could no be duplicated in South Africa; no matter how diligently the Dutch worked, working always with a limited endowment; but did transform these deficiencies into assets. Hostile, challenging, demanding... Yes. Limited — ?

(What follows will also cover your query about the vanishing wildlife.)

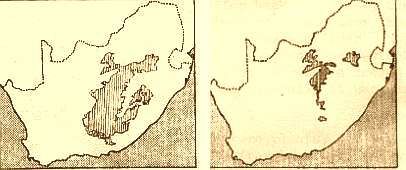

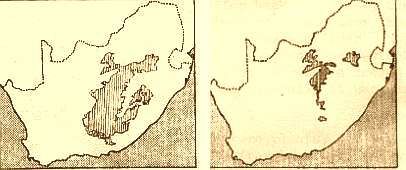

An initial approach would be to try and draw a picture of what the veld looked like when those early pioneers arrived. The work of botanist John Acocks gives us a clue. His veld maps show, for example, extent of the lush, sweet grassveld in 1400 and in 1954:

Once the sweet grasslands billowed all the way from Somerset East to Bethal. Many of the first missionaries, travelers and hunters have told how they found millions of head of game grazing up to their bellies in the grass that grew tall when the rains were good, or how the animals rekked, driven by the hunger madness in the great droughts when the grass did not become lush and green.

Through the ages the grass roots helped by the cold nights and warm days and the heavy thunderstorms also "made" the soil of this plateau, which lies between 4,500 to 6,000 feet above the sea. Here Nature 'farmed' with her wild animals and 150 species of grasses of the region. Then men came - killed the game with guns, grazed the grasses with cattle and sheep, and ploughed the soil that was mostly sandy or sandy loam. In the lands where maize grew, the soil lost the structure of crumbs given to it by the roots of the grasses and it became so sandy that it was easily washed away by water or carried by the strong winter winds. The cattle grazed far and wide and ate only the most palatable grasses so that their place was taken by harder type. The veld was also kept short by the sheep and the good grasses did not come into seed.

The second map shows the small patch of sweet grassveld left today. The place of this grassveld, which is disappearing just like the herds of game, is being taken by the Karoo type and behind this again comes the desert. At the present rate of advance the Karoo will have reached the Vaal River and the desert will be as far as Bloemfontein in 50 years time. Then we will probably have a little sweet grassveld left in the black turf soils around Standerton and Bethal.

The grassland plateau of South Africa has been called the hunter's Paradise Lost. Before the farmers trekked in with their livestock and ploughs, there must have been an untold abundance of animals both in numbers and species. This veld was the heartland of the large vegetarian mammals of Africa. Ever since their evolution they had been delicately adjusted to their environment and required a constant and abundant supply of grass and water under a limited range of conditions. The permanent water points were a key factor in the distribution of game on the vlaktes. Where conditions were suitable, the herds were enormous, but they trekked about and could not stay in any area longer than the water supply lasted. Even if they trampled out the grass around the waterhole, they could graze quite a distance away.

It will never be possible to quantify this lost ecosystem of sweet grassveld in a rainfall area that faded from 30 inches in the east to semi-desert in the west. But the hunters tales and relict patches of its natural state indicate what it must have been like.

"Here was an amazing African climax community that was the ultimate biotic expression of the potential of climate and soil. Nature was showing how she could "farm" when man was not the manager turning up the grasses with his plough and tractors, but armed only with bone and stone tools, then with bow and assegai, digging pits at the waterholes to trap the animals for food. What is more, the symbiosis of soil, grass and animals life was such that it could have lasted forever unless there was a change of climate.

"Then a new kind of man - armed with barbed wire as well as bullets - came to take over this Eden, this going concern that had been built up by nature ever since evolution produced its most wondrous plant, grass, early in the Miocene about 20 million years ago. And then, in less than a century, European man with his advancing technology almost destroyed this wonderful creation of biological evolution."

It is difficult to say with certainty how much game there was.

In Soil is Life, T.C. Robertson attempted a calculation based on the fact that in the Orange Free State, an area slightly smaller than the sweet grassveld where the game roamed, there grazed eight million sheep and two million cattle. In terms of stock units this is equal to peak game population of two million wildebeest, half a million each of eland and quaggas, and a total of six million blesbok, springbok and hartebeest. (The proportions of game were based on observations by Dr. Andrew Smith in his diary.)

• One unforgettable day in 1849 the people of the little Karoo village of Beaufort West heard a roar in the red dawn as if a strong wind was blowing before a thunderstorm. Then, according to J.G. Fraser who recorded the event, they could hardly believe their ears when the sound of the wind changed into the trampling of tens of thousands of hooves on the red earth. But they saw right before their eyes in the dusty streets the flow of a horned flood of all kinds of game. wildebeest, blesbok, quaggas, eland and springbok, mostly springbok, tens of thousands of them.

• Gordon Cumming, one of the most reckless hunters who ever fired a shot in the veld, gives an equally vivid description of the trekbokke he saw on the move between Cradock and Colesberg. In his book, The Lion Hunter of South Africa, 1858, he tells how he stood on the voorkis of his wagon watching the springbok pass 'like the flood of some great river,' and then the vast legions continued streaming through a neck of the hills in one unbroken compact phalanx.

He saddled his horse, rode into the midst of them and shot until he cried out: "Enough!" A few days later a much bigger trek passed and the landscape became alive with this amorphous mass of living creatures. He could give no estimate on the number of antelopes he saw that day, but he had no hesitation in saying that "some hundreds of thousands were within the compass of my vision." An old Boer who was with him observed that it was a "fair trek," but in his days he had seen treks that covered many valleys "as thick as sheep in a fold."

• For forty years after the Trek, there came the hunters who, first with muzzle loading guns and lead bullets and then with accurate rapid firing rifles, slaughtered the game - not in a spirit of cruelty and wanton destruction, but because the tusks, the hides and the meat were wealth. They were living off the veld like the Bushmen (San) but more efficiently with rifles. They saw such an abundance of game that they never believed it could be destroyed; that the quaggas, easy to hunt and favorite meat of Hottentot servants, would become extinct; that the mountain zebra and bontebok would only survive in small herds - that a farmer on the plains of the Free State would someday prize and protect a few black wildebeest and springbok that grazed like pets in his garden.

• The hunters also tamed the veld by shooting the carnivore, the lions and leopards - all except the jackal. Slowly there followed in their footsteps the shepherd and the herdsman. But the veld was not yet tame enough and at night the sheep and cattle had to be protected in stone-walled kraals. The kraal and the jackal have become the symbol of the beginning of erosion on the veld. Every night and every morning the sheep trampled footpaths from their grazing ground to the kraal, and when the thunderstorms came, million of tons of raindrops hurled onto bare earth where there were no grass blades to break the fall. They rushed off in torrents and washed the first footpaths into gaping dongas.

• The Karoo was not always bare soil dotted with bushes "each in its own little desert." It was once covered with perennial grasses, the remnants of which are still found by botanists. Unless conservation measures are planned, in one hundred years desert will encircle Bloemfontein, the Karoo will have crossed the lower reaches of the Vaal and its advance guard will be pushing past Vereeniging toward the headwaters. Only a small patch of sweet grassveld will be left on the black turf soils of Standerton and Bethal.

How some of those early travelers saw the land

• VAN RIEBEECK found eland on the slopes of Table Mountain; hartebeest, too, was plentiful in the vicinity of Cape Town. Just beyond the Cape Flats in 1702, an elephant was shot. As late as 1798 herds of 500 elephant were found at Knysna. (yet, by 1772, Thunberg already complained about the scarcity of wild life on a journey from Hex River Valley to Graaff Reinet.) A few hippo lingered for many years near the mouth of the Berg River, less than 70 miles from Cape Town - the last is said to have disappeared about 1784. Van Riebeeck and his party found a hippo wallowing in swampy ground about where Church Square, Cape Town is today.)

• English hunter WILLIAM FINAUGHTY, on the Free State plains in 1864: "I would not have believed that so many wild animals could be together in one place. As far as the eye could see was a teeming mass of animals including black wildebeest, blesbok, springbok, ostriches, quaggas and blue wildebeest."

• JACOBUS HATTINGH, who fought in the Battle of Blood River, was a 17-year-old boy when the wagons of the Trek rolled through Basuto country. Further north, beyond the Modder River, the Trekkers found the game glossy and round from the good grazing and so they called it the Vet River "A deserted wilderness," wrote Hattingh, "of lions, leopard, wild dogs and jackals pursuing the buffalo, wildebeest, blesbok and other herds."

• Coming down toward the Trekkers from the north was Captain CORNWALLIS HARRIS. When he crossed the Vaal, he saw the grassland plains to the south "boundless meads covered with luxuriant herbage and enameled with rich parterres of brilliant flowers. These were animated by drives of portly elands, moving in slow procession across the silent landscape, and treeless.: He sketched and described the same scene that had met the wondering eyes of the Voortrekkers: the galloping herds of hartebeest and quaggas, the swishing white-tailed black wildebeest, the elegant blesbok and springbok leaping in curved back display, the long strong of morose buffalo and, again, the enormous eland "grazing in herds like tame cattle." (summer of 1856)

• SELOUS estimated that if a census could have been taken early in the 18th century of all the animals south of the Zambesi, buffaloes would have proved to be most numerous. Herds of them were still being hunted around Cape Town in 1705 by Kolbe.

• When a party of Trekkers came to settle in the valleys of the Witwatersrand there were hippo in abundance in that swampy vlei at Natal Spruit near Alberton (1840)

There must have been thousands of hippo in the Vaal and Orange Rivers and their tributaries. According to Lawrence Green, the last hippo was shot in a deep pool near to the mouth of the Orange River in 1925 by Hendrik Louw "who loved rifle music."

• When the Portuguese traveler De Santa Rita visited the Soutspansberg in 1855, he estimated that 200,000 pound of ivory was exported every year.

In 1863, ivory worth £40,736 was exported through Port Natal, most of it from the Transvaal. In 1864, £26,254; 1865,£19,154. In 1864, calculations show that 1000 elephant had to be shot to provide the ivory exported.