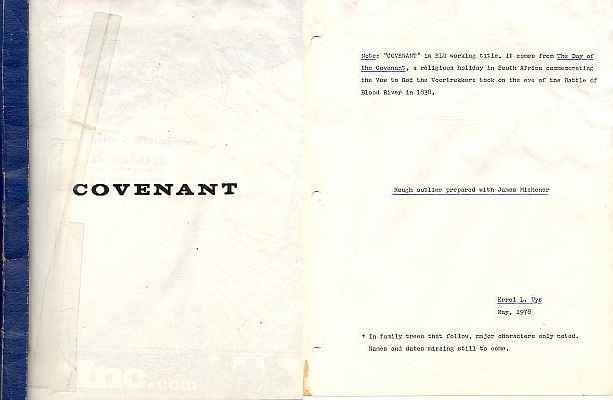

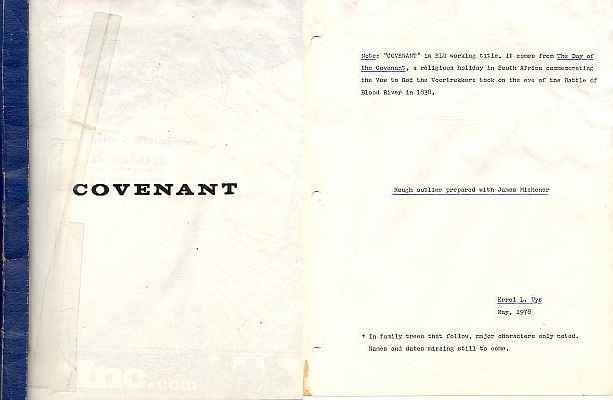

I went back to New York after the St. Michaels plotting sessions, cleaned up our notes and typed a Rough outline prepared with James Michener - May, 1978. On the frontispiece, I used the title COVENANT with this note:

"COVENANT" is ELU working title. It comes from The Day of the Covenant, a religious holiday in South Africa commemorating the Vow to God the Voortrekkers took on the eve of the Battle of Blood River in 1838.

This thirty-three page outline is, of course, a concise summation of countless ideas Jim and I tossed around over those two weeks. For both of us, it was a route map to the many twists and turns the story would take as our thinking developed.

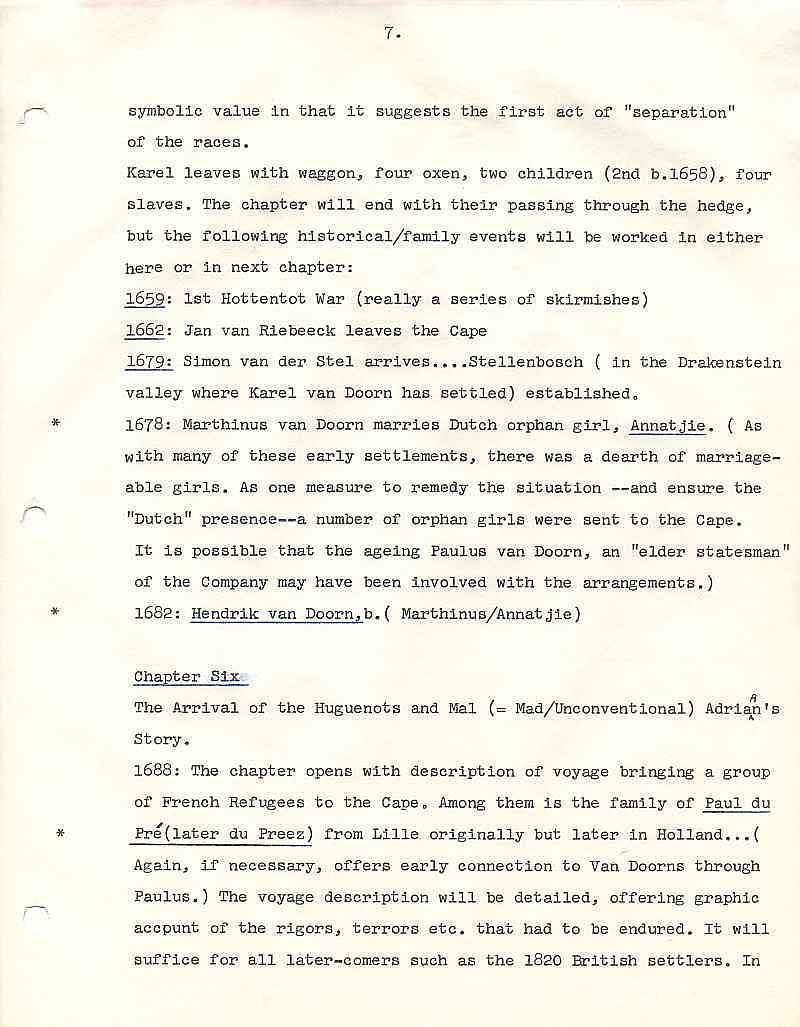

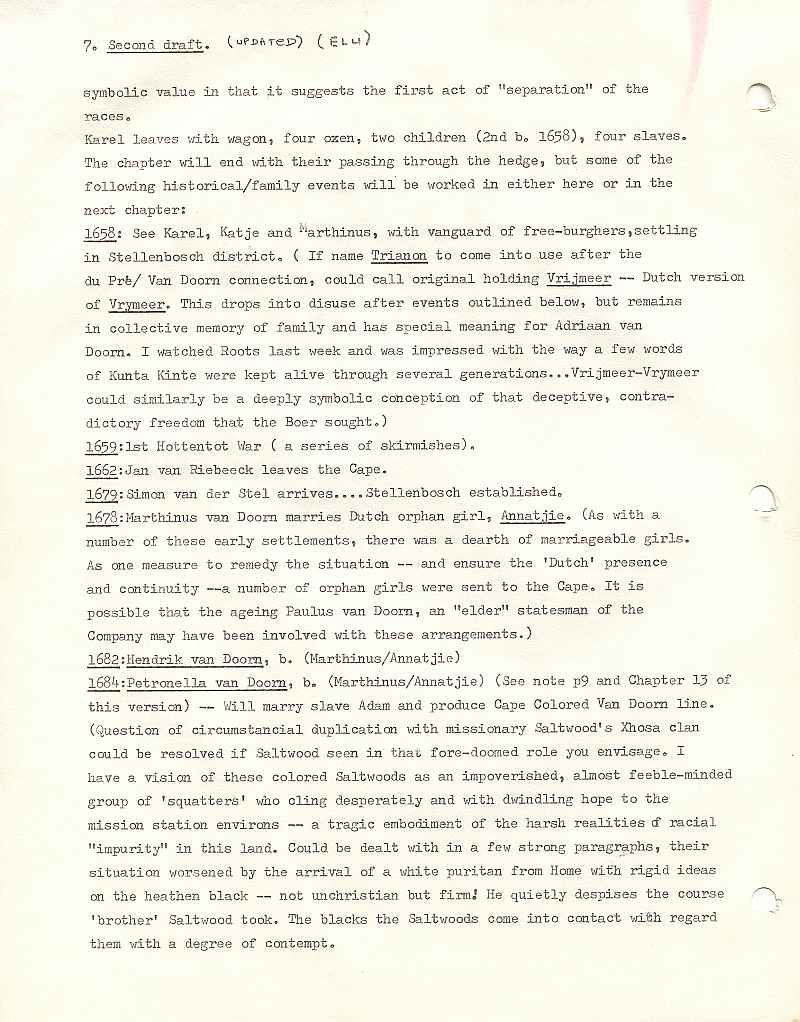

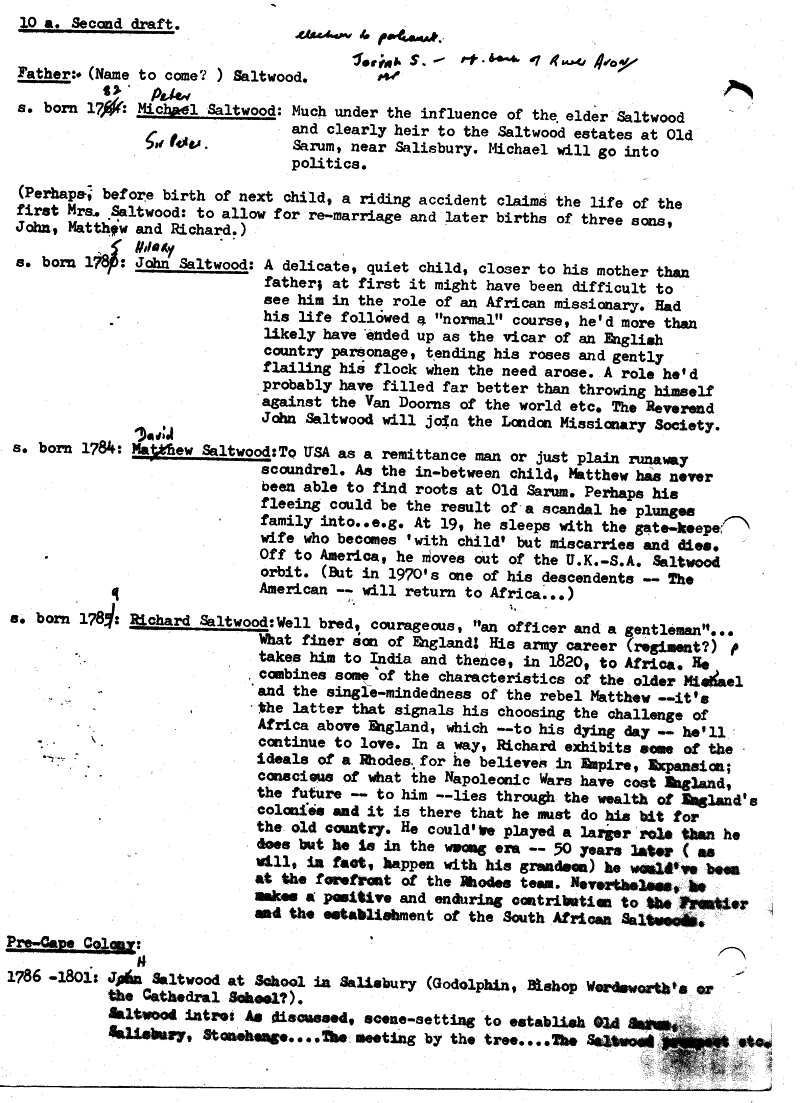

Though Michener's April 1979 comments specifically refer to the outline as I drafted it in May 1978, the pages he comments on are interlaced with plot revisions made by me as we went along. So, for example, the development of the Saltwood story, which gives a very good idea of our ongoing "brainstorming:"

On May 25, 1978 Jim wrote to me from Honolulu:

Honolulu, Hawaii, May 25, 1978

... I think one of the best things I could have done in preparation for my research is to visit Hawaii to see a rather fine society, no better than Johannesburg, nor worse than Marseilles, but just a good functioning agglomeration in which a large number of people are finding happiness and self-government, and consumer goods; and to realize that in south Africa everyone of these people would be proscribed to a terribly limited life, and that all their creative energies would've been diminished if not destroyed. What an incalculable loss! It makes me think of the mainland and how much poorer we would be without the contributions of our Cape Coloured: O.J.Simpson, Lena Horne, Ralph Bunche, Diahann Carroll, Sidney Poitier, and the rest. How we would have cheated ourselves! It seems to me that someone advised the Afrikaners poorly when the decision was made to divorce this reservoir of talent from the mainstream.The more I study and think, the more heavily inclined I am to make at least one of the Englishmen a missionary, perhaps the very first although I haven't clarified that. I find myself driven in this direction for a variety of reasons: (1) In whatever I read I find the Dutch really despising the missionaries, their own as well as the English, so the symbol must have vitality; 2) I find the missionaries insufferable, which always makes for a good character; and 3) I find them with startling frequency to have been right or on the verge of rightness. I do not (Michener's underscore) know how to resolve this conflict, but let's give it the most serious thought. Such deep feelings on my part usually turn out to be right.

Pleasantville, New York. June 2, 1978

... Our missionary could well be Vera Stanworth's brother - a likelihood in that someone would have had to accompany her out to the Cape or we get an over-heroic figure doing the long voyage etc. It could tie in well and offer an 'insufferable' young man who would be at his peak when slavery ends. He could be cranked into that 1813-1833 period without difficulty - and could be a valuable link to the Xhosas. Perhaps, shift him over to Natal after that, have him in Port Natal when Piet Retief gets there. Just rubbing salt in old wounds and strongly underlining the Boers' irritation at the English presence......I have the rough notes from our meeting all typed up and pretty well organized. As a 'working title,' I came up with one word that my interest you. It certainly covers the Afrikaans element and if one thinks of the spiritual, the creative process, the 'covenant' that all men have with Mother Africa, it comes up as a strong label for black or white: COVENANT.......How I agree with your comments about the terrible loss to South African society by the failure to use so many talents there! It's a point that could well be worked in through the experiences of Daniel Nxumalo during his time as teacher at the Vrymeer mission school.turning bright, talented youngsters into bright, talented farm laborers etc. It could also be an observation Craig (Saltwood) makes through his contact with Shamilah's friends.

London,15 June, 1978

... The suggestion that the novel be titled Covenant is a sturdy one. I had already planned that the most important paragraph of the book come at the conclusion of Blood River, something like this:"What they did not realize was that men and women are always free to enter into a covenant with God, but this does not mean that He is obligated to enter into a covenant with them, and especially when they have determined unilaterally the terms of the covenant."

You can see that this concept, properly handled, will lend itself to excellent elaboration, and covers, indeed many of the strands of the proposed book. But I would not like, at this time, to fix upon a title, for I've never done so until the manuscript was finished, and even then have usually left the final decision in the hands of Random House. I am not good at titles and feel that naming a book too soon during the gestation stage is a sure way to put a curse on it. But I see much merit in Covenant; it's better than anything I might have had in mind, and I will keep it strongly on file.

I find myself quite uneasy with the English name Stanworth, and the fact that I cannot remember it when I am working through ideas gives me not only considerable worry but also a premonition that it will not serve. It lacks character, and since I am now working on English materials in an English setting I am most desirous of implying strong character. For the present I am thinking in terms of something like Saltwood, which I like very much, or Stamp, which is good except that in my last novel I used the name Steed to excellent effect and would fear repeating myself with another one-syllable name beginning with St-

Working here has clarified many gray points. I spent two days at Three Bridges and found it horribly unsatisfactory. If my Saltwoods came from there I wouldn't want to have much to do with them. Had they been total exiles, Three Bridges might have explained their flight, but since I want the English home to remain a magnet, I knew that I had to find something better. I have done so in the Cathedral town of Salisbury, some 75 miles west of London. It is a place that one might remember in exile and it has three virtues for me: (1) It is near to Old Sarum, about which I once did a lot of work and which will work well into the novel as I see it, most tellingly in fact. (2) It is also close to Netherhanpton where Sir John Newbolt lived, who wrote the great poem about cricket, and since I want one of our Saltwoods to cast the deciding vote not to send a black or coloured cricketer to England back in the 1880s, thus establishing the pattern that would prevail (a good account of this in They Were Also South Africans) there could be a good relationship. (3) Most important, Stonehenge is at hand and the Saltwoods would know it intimately, which can become important vis-à-vis Zimbabwe. I am visiting all these sites tomorrow for the third time to see if they seem as productive in review as they have gone in prospect. But I think Salisbury is our locale.

I am bewildered on a point which may seem trivial but which looms as most important in my story-telling. Should the Saltwood boys attend Oxford, which is rather nearby, or Cambridge, which is distant? I go round and round on this. If Oxford, we have Oriel which Rhodes attends, and also the Oxford Players performing at Stonehenge. If Cambridge we have that glorious Cam, and King's Chapel with the Rubens, and a kind of daring educational policy that Oxford did not have. We should think about this, and I shall be visiting both universities again shortly to strengthen old impressions. As of now I incline slightly toward Cambridge.

The work here has settled one problem. The visitor in the last charter must be an American, one of the Saltwood line who emigrated to America when the others went to South Africa. We do not hear of him for 180 years, but he comes as an engineer with all the virtues of the Swede I had proposed and many plus reverberations. This plotting is quite clear and increasingly promising, so we may consider it settled.

I am at a total loss about the missionary; I liked your suggestion about the brother-escort but now feel it has got to be a Saltwood. The more I work with this material the more convinced I become that that is the way to go. (We shall have so many characters as it is, that the closer we weave the net the better; keeping the name Saltwood before the reader will be an asset, and the more varied the performers under that name the better.) But I am not doctrinaire on the matter'. Please continue to give this your most careful thought, as mine produces little except a conviction that we need the character and can use him to tremendous effect if we can come up with the proper structure.

I've put all my thoughts and ideas about the Reverend John Saltwood on paper. They certainly convince me that the meddlesome missionary approach is indeed the most correct you could have chosen. With the younger Saltwood, the office, the frontier-drama is still there but the Godly-son-of-England can bring a marvelous depth, symbolism and moreAgain, I've worked this against that first 'rough notes' - though it's almost 100 per cent revised. I suggest ways in which earlier concepts may be worked into the new framework. All seems capable of being handled without much difficulty.

I'm much taken with the sad figure of Saltwood, so involved and yet so lonely upon this strange land where he has chosen to make his stand for God. He often tries so hard, but cannot come to terms with his adversary, Africa, for faint-hearted and wavering, he lacks the horizonless vision to see beyond his present predicament. When he finds a 'vision' it is fore-doomed, tragic. One wants to be next to the man - to give him that nudge toward reality. But it can't be, and he seems destined to choose the wrong path. Perhaps not 'wrong' in the sense of just or unjust - not essentially so - but woefully misguided.

Errol Lincoln Uys, plotting notes for the Engish family in Michener's Covenant -- Read more pages - Plotting Saltwood family

I continued to revise and add to the story ideas amid the intensive research that followed and later during the manuscript stage. So, for example, I provided twenty-one pages of plot lines and leads for Chapters XI and XII, the education and achievement of an Afrikaner 'puritan' beginning with an image of young Detleef van Doorn in the immediate aftermath of the Anglo-Boer War:

When the time came for Michener to write the first draft of the novel, some of my ideas would be scrapped but most found their way into The Covenant alongside Jim's own storytelling, as one might expect in any intimate collaboration between two writers.The Education of a Puritan (excerpt from ELU plotting notes)

1902 May 31 Treaty of Vereeniging ends Boer War1903 The rains came late that year... Much in the opening scene at Vrymeer evokes picture of the past, of the primitive conditions of early man here, of the Great Drought that drove the San away from this valley. First, we see Paul de Groot in the upper part of the valley where his farm Blinkfontein lies - like a broken, homeless dog, cowering in the ruin of his farmhouse. Even his blacks live better...

A few miles away, the neighboring Van Doorns: Jakobus (b.1848 d.1918), Johanna, his daughter (b.1880 d.?), her husband, Piet Krause (b.1876 d.?) and the child, Detleef (b.1895). They are living in an old wagon from the Trek?) outspanned behind the ruin of Vrymeer. The woman and child sleep in the wagon, the two men on the ground below...

In the town of Venlo is Miss Emmaline Broadhurst, one of Emily Hobhouse's helpers, passionate pro-Boer/anti-imperialist, now trying to organize a school for the children of the area. She has heard about Detleef, and is on her way to Vrymeer in her donkey cart when the thunderstorm breaks; the sparrow-thin spinster, age 33, arrives at Vrymeer as the deluge ends. First, when he learns that she is English, Jakobus van Doorn fingers his sjambok . Johanna remembers her as one of the Hobhouse girls and tells Van Doom that he must listen to what she has to say about Detleef. Van Doorn argues about the language of the conqueror in the mouths of slaves etc. . an argument that will be repeated by the blacks years later, when the Bantu Education Department, inspired by men with a 'separate' vision like Detleef van Doorn, gets underway.

From 1903 to 1913, Detleef will be tutored, together with the other children of Venlo, by this remarkable Englishwoman. (but a time will come when, with the Broederbond fixing its grip on the town, Miss Broadhurst is no longer needed.) During this period, Jakobus van Doorn commences the reconstruction of Vrymeer. Approached with the suggestion that he go back to politics, he refuses, unwilling to participate in anything associated with England. Though gone, Milner remains the personification of evil, with van Doorn recalling Milner's December 1900 statement: " If 10 years hence there are three men of British race to two of Dutch, the country will be safe and prosperous. If there are three of Dutch and two of British, we shall have perpetual difficulty.