A week later Tony hosted a second lunch with Michener which I attended, the three of us getting together in the wood-paneled elegance of the University Club, a Renaissance palazzo on the sunny corner of 54th Street and Fifth Avenue. We sat in the great red and gold lounge where New York's finest clubmen gathered, the news of the world spread out across their laps, an older member nodding off here and there. Here and there, too, a dress or skirt might be spotted. Women were admitted as guests and allowed to eat off the club's plates and drink its highballs but forbidden membership, a ban that would survive for another decade.

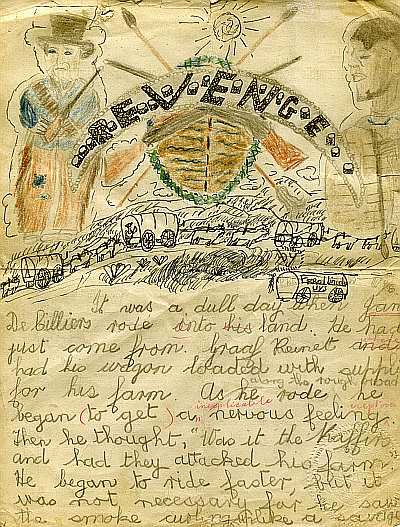

Jim and I hit it off immediately, just how well I would find out as our working relationship grew but within minutes of sitting down, we were away and running. Or, I should say I was, for Jim did the listening and I, the talking. He'd been thinking casually about a South African book since meeting the country's warring tribes seven years earlier. I was ten years old when I wrote Revenge, a forty-page settler saga penned on the back of worthless share certificates tossed out by my mother.

It was a dull day when Jan de Cilliers rode onto his land. He had just come from Graaff-Reinet and had his wagon loaded with supplies for his farm. As he rode along the rough road, he began to get a nervous feeling. Then he thought, "Was it the Kaffirs and had they attacked his farm?" He began to ride faster, but it was not necessary for he saw the smoke curling up like a savage beast and disappearing into the sky. He did not want to see the mass of ruins of his house. He was about to turn away, but he thought again. "Perhaps there are survivors." He grabbed his gun, hid the wagon and made his way to his house. On the way his native servant leaped out of a bush with blood streaming from his head and said, 'Baas! Come quick missus is still alive and son is dying. Go! Quick!" "Come on," said Jan but he was just wasting his breath for his faithful native servant swayed, staggered and fell dead.

Jan took an unhappy glance at him and made for his house. Just as he entered a Kaffir raised his spear and threw it. He did not know where it landed, but he did not take notice as his life was at stake. He raised his gun and fired. In a moment there lay the Kaffir, dead as a stone. But this was not all, in a corner lay his beloved wife, Anna. In another Johann his son, but his daughter was no where to be seen. Suddenly he heard a low muffled groan, it was his son. He heard his son mutter, "She was captured." He then thumped on the ground and he was dead. Jan slammed the door closed and went outside. He saddled his horse and he left the house. What would he do now? In the back of his mind, the one word rang out "Revenge." "R.E.V.E.N.G.E."...

[NOTE: Usage of the word "kaffir" in a modern South African context is a pejorative, as unacceptable today as its American counterpart.]

I look at this grim tale in the pencil strokes of a child's hand (and a lot grimmer it gets, too, as vengeful Jan de Cilliers leads a murderous attack on the Xhosa) and I think of the boy who would come to share a thousand stories with Jim Michener a quarter-century later. The setting of Revenge and The Englishmen are the same but to get from one to the other was more than a journey in time and place. I had to leave the laager and seek a path beyond a dry stony veld that hardened the hearts of many in South Africa.

From the time I saw my first article in print - Happiness is an Unprejudiced Mind - to this day, I've considered one attribute paramount for a writer: enthusiasm, to have passion, the entheos of the Greeks, to be possessed by a god. At the University Club that day, I raced from one topic to the next and leapt from century to century with seven league boots and nine muses flying along with me.

Michener had spent a month in South Africa in October 1971 and earlier made short trips to Mozambique and Angola. Out of his South African sojourn had come a ten-page New York Times Magazine article, "The Five Five Warring Tribes.

I was not to know of the existence of this article until I began work on these notes about The Covenant. Jim never mentioned it to me, a curious omission but not out of character.

He held things so close to his chest that when he was courting Mari, he kept his love a secret from his two best pals, Herman and Ann Silverman. The first the Silvermans, who were friends for fifty years, knew of Mari Yoriko Sabusawa was when they picked up a copy of Life magazine in a Rome hotel in the fall of 1955 and saw pictures of the couple's wedding in Chicago. Jim had driven them to the airport three weeks earlier without saying a word about Mari and their impending nuptials.

Michener's trip to South Africa in 1971 left him with as good a picture of the country as any visiting writer, including his exposure to irrationalities of so-called "petty" apartheid, as opposed to the grand plan for separating the different tribes. He encountered bizarre rules such as one that permitted whites and blacks to play tennis together on private property, provided the court wasn't visible from the street where passersby might glimpse the match. But our first meeting revealed that Jim also had a long trek to make across that stony veld before he came to know the people living there.

There was, for example, his perception of the Zulus. On his 1971 visit, he toured Kwazulu in Natal province, the tribal homeland created under grand apartheid. The New York Times feature has a photo of Jim on a gold mine outside Johannesburg watching Zulu miners perform traditional dances, their work clothes exchanged for furs and skins. The dances delighted tourists though not nearly as much as the Zulus themselves, for like today's hip-hop generation, the songs of the foot-stomping miners jabbed at the belly of umLungu, the white man.

"My thinking is to bypass Natal and the Zulus," Michener said at lunch. He wanted to do justice to the black tribes and planned to focus on the Xhosas. "I can get all the value I want out of them." The only interest he had in the Zulus lay in the fact that they'd driven the Xhosas south to the Cape frontier, where his readers would find them.

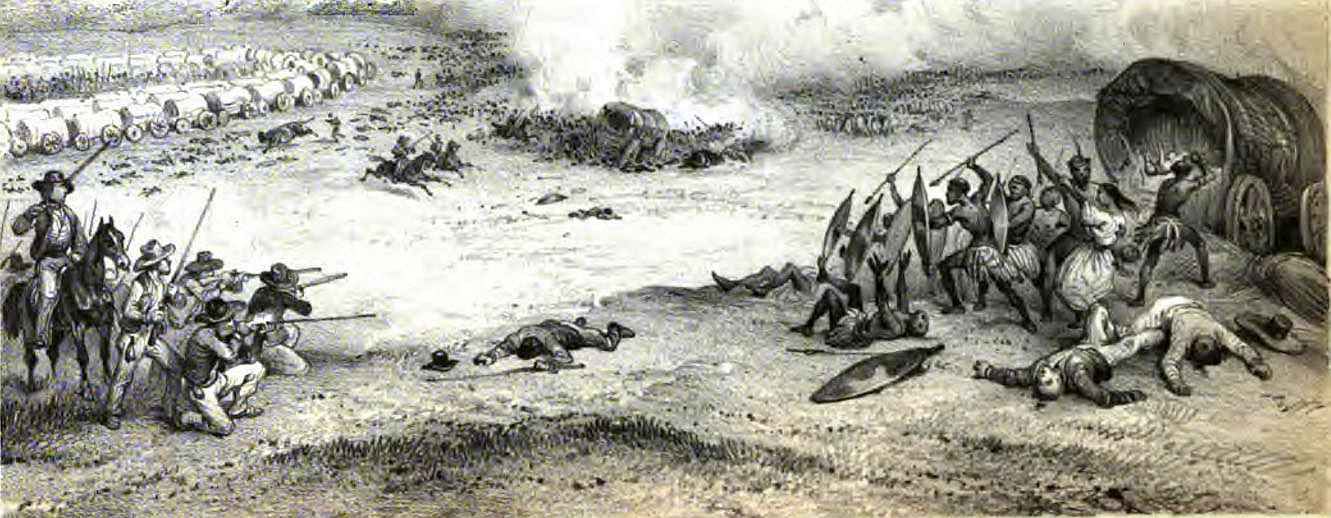

I can't recall exactly how I put it, for I was after all a minnow swimming in waters deep as the ocean sea. I told Jim that it was impossible to write a book such as we had in mind without the Zulus. What of Shaka, the black Napoleon who forged a warrior nation out of a patchwork of Nguni clans? And Dingane, his treacherous half-brother, a bloodthirsty tyrant who murdered Shaka and sat on the throne when the Voortrekkers, the Boer pioneers, crossed into Natal? What of Blood River where the Boers made a vow of obedience to God on the eve of battle, four hundred and sixty four against twelve and a half thousand Zulus? What took place on the morning of December 16, 1838 was the defining moment for the Afrikaner people, a victory that determined their future in a land they believed God set apart for them.

I remember telling Jim about my heritage, adopted and raised by an Afrikaner family whose roots went back to the Voortrekkers and long before the Boer migration. My line of Uys's were related by marriage to the Voortrekker commander at the Battle of Blood River. My mother, Hester Johanna Maria Uys, was seven when the British invaded the Boer republics: she survived two years in concentration camps at Bloemfontein, Bethulie and in the Cape Colony.

A decade after penning my childhood Revenge, I was sitting with Joey Uys taking notes as I listened to my mother's stories of the African veld.

"Dammit, Errol, must you ask me all these questions?" Joey would complain.

"Yes, mother."

Whether we spoke about an Orange Free State farm in the nineteenth century or the English prison camps, the notes I kept show just how persistent I was.

A.M. (1) Woken with enamel cup of coffee and big boerebeskuit. Dipped into coffee. 'Raw' coffee roasted in outside ovens where they made bread. Round oven built of mud. Bread baked in paraffin tins. Three loaves to a tin. Coffee grinder screwed to kitchen table. Beans pushed in with spoon. Smelled beautiful, fresh, aromatic. Fruit trees. Dried peaches and tamaletjies - dried fruit rolled in fat and wrapped in muslin. Biltong hung outside in trees. Fridge under tree. Double-sided box with gravel-like stones in recess. Zinc pan with holes on top. Water dropped onto stones. Wind blew through holes to cool.

A.M. (2) Mother washed girls in brass basin. Long calico nightgown. Rubbed teeth with a cloth. Soap made from fat. Put on dress and combed hair with big comb. Square framed mirror on table. Still dark, cold. Adults up and dressed.

6 A.M. Dining room. Family Bible with names, births, brought to table. Leather cover. Brass clasps on back and front. Large wooden table. All seated as uncle reads from Bible. Still seated, sing a psalm. Then on knees around table and pray. A white tablecloth for breakfast. Bread on table. Butter in soup plate. Enamel dishes. No porcelain. Knives, forks with steel handles. Scoured with sand. Plain white enamel jug. Milk. Mielie pap. Yellow sugar. Children silent. Had to ask if wanted anything. Fearful. Prayers and singing after breakfast. Then children play outside back door.

"So many questions, my boy," my mother said. "Why are you asking me all these things?"

Today I know the answer. So did James Michener, who never met the child of the veld, though her story came to mean so much to him.

Michener, Oursler and I left the University Club that March day with a loose plan on what to do next. Jim was going to give serious attention to a South African epic. Tony's mission was to find a modus operandi between Reader's Digest and Jim's publisher, Random House. I was to continue polishing my outline.

I'd no part in talks between the Digest, Random House and Michener's agent at William Morris Inc. They agreed that Michener would engage my services as editor/researcher and pick up my Digest salary and expenses for as long as he needed me. No monies would pass hands, the fee to be written-off against future payments by the magazine for rights to Michener's book.

The negotiations were still underway when I finished my outline and sent it to Jim at St. Michaels in late April 1978. He replied immediately:

St. Michaels, MD, 22 April 1978

For Tony Oursler and Errol Uys,

About an hour ago Mari brought me the mail and I had the pleasure of reading Uys's notes about a proposed book on South Africa. I was impressed by his organizing ability, his thoroughness, and his keen insights into the problems of arranging a mass of material so as to be usable, especially in fictional form.It became immediately apparent that he is prepared to start talks with me right away, because we have both done a great deal of thinking on this matter, along our separate lines, and we have come up with striking parallelisms, as I suppose any two reasonably intelligent persons would, faced with identical data.

I therefore think it prudent that Uys and I meet as soon as possible, down here in Maryland, to spend seven or eight days together wrestling with big ideas.

It is important, I think, for me to react to Uys's outline before we meet. I saw it for the first time an hour ago and responded most favorably to a great deal of it. But you must understand that I have been thinking casually about such a project for several years, and specifically for the past month. I have, as you saw from my notebook in New York, my own strong ideas as to what might be accomplished, and past experience has taught me to cling fairly, strongly, but not stubbornly, to my first solid impressions. This I will have to do in the case of a possible South African book.

Basically, the only difference between Uys's outline and mine is that as always I want to take things slowly, avoid the big central occurrences, avoid the big cities that others can write about better than I, avoid the super-dramatic confrontations, lay emphasis upon the physical settings which enclose all of us wherever we might be, and allow the story to unfold with its symbolism implied rather than stated, and its high moral instinct in the yarn rather than spelled out in chapter headings. These are devices and principles which I have worked out over several decades, and they fit my personality and skills, and to abandon them now would be perilous. (Also, they work!)

I think you can see where I'm heading. I found Uys's material one degree too dramatized for me, one degree too novelistic. But I'm mightily impressed with his keen instinct for weaving strands together, and I am sure I could learn something from him. In fact, I would like nothing better than to sit quietly with him and Oursler and kick these strands=ideas about for some days to see which are fruitful for my slower, less dramatic approach.

To be specific, so that you can be thinking along the same lines I am, I have already sketched the material dealing with the creation of the diamond and have everything under control except the facts! Can't find a good account anywhere at all! Conclude that I already know more than any of the writers, and that ain't one-fiftieth of what I need to know. For some years I've had a fine short chapter on Australopithecus and have come to consider it a focal point of this book. This time I have all the material I need, some from studies done years ago, many from recent reviews of new materials, but even so I would want to check each sentence with South African experts, because they discovered him and know far more about him than I do.

Instinct advises me that I ought to leapfrog immediately to Zimbabwe at about 1410, and I am fairly well prepared to do this, having seen the area on two previous trips. But I am impressed by Uys's belief that there out to be two interpositions between Australopithecus and Zimbabwe; the Bushmen and the putative Phoenicians, Arabians and Ophirites. I have done no work on the Bushmen and had planned to play them down in comparison with the Hottentots, whom I want to make a strong feature as those present when the Dutch arrived. I have done much work on the Indian littoral, but not in relation to this book. I visited all the ports, all the rivers and made copious mental notes against the day I might want to use either Sofala or Mozambique Island. But frankly I have not cranked this dormant material into my plans and do not, right now, see how best to do so. I would appreciate your thinking about this.

I have no interest in Uys's Portuguese explorers down the Atlantic side, although I did a heavy amount of work on them when I spent some time in Luanda. (The concept of those stelae looking out upon the ocean is alluring, but I am not strongly attached to them as literary devices.) But as the preceding paragraph indicates, I have done much work on the Indian Ocean side, either with the Portuguese or the Arabs, and am somewhat taken with this. Certainly, in the Zimbabwe chapter I would want to use Sofola; and I have always thought that one of the mournful tragedies of South African history, from the local point of view, which I am able to feel instantly, was that they never acquired control of Lorenço Marques, whose loss seems even now incalculable.

Naturally I would not want to attempt this important and difficult book if I did not do ample justice to the great black tribes, and I have always had this in mind from the time years ago when I studied the Zulus intensely, visiting their new lands, their old battlefields, their university and their present-day homes. But I'm damned if I see clearly how best to handle this. I had thought I would focus on the Xhosa as the people who were forced south and west by Shaka, and this still appeals. But I belatedly see that the story is only half told if full emphasis is not given to Shaka, his antecedents and his followers in addition to Dingaan. But every instinct tells me to wait on this till after the Dutch have been established. It makes for a better book, I am convinced. I am, however, open for suggestions as how best to introduce the material.

I have great interest in the shipwrecked Haerlem of about 1648 because I want to stress Java and Batavia as counterweights to Cape Town, and it occurs to me it would e fruitful to use the Haerlem incident as the one way to introduce my continuing Dutch family. In my plan of some years ago, this would form Chapter IV and would get the story launched, insofar as the Europeans are concerned. But I find absolutely nothing about the Haerlem !

Like Uys I want to stress the Huguenot strain, but as of now I have no clear plan for accomplishing this. I deem the French influence to be rather stronger than the average writer indicates; many of the profound strains of the Dutch-Boer-Afrikaans character show a clear Huguenot component. But this can be easily worked out as the characters move across the pages.

My Chapter V, assuming that the French do not merit a chapter to themselves but an ancillary treatment, would leap directly to the Xhosa Wars and the coming of the English as a kind of afterthought. This could be a very solid and focal chapter, stressing the confrontation of Xhosa-Dutch and Dutch-English. But I have never done much work on the Xhosa, except as they were caught in Zulu history, and would need a lot of specific work to make myself competent. I much prefer the Zulus and the Matabele, but the more I think about Afrikaner history, the more significant the Xhosa become, a fact I did not appreciate some years ago.

Then the trek, on which I am fairly well informed. I have always thought it ought to be done as the South African version of the American trek to the west, and the Russian trek to the east, and I want to place it in its proper physical setting, comparing it with those other great treks which were so much more significant in terms of numbers of people involved and miles covered, and so much less important psychologically.

I had always intended, as you know from what I told you, to bypass Natal, which meant also bypassing Dingaan, because I have always been much more interested in the trekkers who did just that. I felt that I could get all the values I wanted from the Xhosa, but what Uys said at our meeting made a deep impression on me and I have restudied this issue.

Blood River is too important to be ignored, even though all my antecedents as a writer warn me to do so, and I am beginning to see how I can digress to that tragic scene and then get back on what is for me my main line. In fact, this can be done with certain advantages and should be, primarily for two reasons: Blood River is too deeply ingrained in Afrikaner memory to be ignored and is too good a phrase to be wasted; and I now think that the blacks I want to follow in the powerful later chapters ought to be Zulus.

And there my specific planning comes to a halt. (In my earlier notes I leapfrogged almost directly to the workings of the pass laws, which is too enormous a leap for a book of the kind I now visualize.) I want of course to establish the diamond theme, but not too heavily. I do not want to make much if anything of the Rhodes-Kruger confrontation, for others have done this commendably. Nor am I concerned about the Uitlanders or the fracases between the two Republics.

Whatever I decide upon this lacuna must lead to the Boer War, which I have fairly well structured. But I am not making any firm decisions because I want to see what happens to our characters in the preceding episodes: Boer heroes; English actors: Black majority.

As they move into the Twentieth Century their obligations become clearer, and I have always had this fairly well in mind: much emphasis on 1938-1945; great stress on the intellectual conflicts of the 1948-1960 period; and in the final chapter a focus on perhaps only three central figures, each of which grows out of the preceding periods.I have already given some thought to Oursler's idea that an American enter the final scenes, and now I see that Uys had the same idea. There may be some value in this: a fresh figure, a new view, a premonition of the 1990s. I don't want to use the diamond melodramatically, but if it is well handled in the opening chapter, and then again prior to the Boer War, there could be a way of utilizing it within the limitations I set myself. At any rate, I'm think about this and have so far come up with nothing. But the idea does persist, so maybe it's a good one.

Now you know all I know and the next move is yours.