I arrived in the United States nine months before meeting James Michener, my passage to these shores paid by Reader's Digest. I joined the Digest in London in 1969 after working on newspapers in Johannesburg, Cape Town and London. In 1972 I was appointed the first editor-in-chief of the Digest's South African edition and held the post for five years before being offered a position as senior international editor at the magazine's headquarters in Chappaqua, New York.

At noon one day, five months after putting down roots at the Digest's head office, I stood outside the main entrance of the handsome red brick Georgian building waiting for a fellow editor who invited me to stroll through the grounds with him.

The bells of a Flemish carillon in a cupola began a medley of inspirational music. I looked up and beheld four winged horses poised to take flight to the four corners of the earth. I felt a thrill gazing up at Pegasus, symbol of Reader's Digest, spirit of the Muses and war-horse on whose back Bellerophon rode against the Chimaera.

Fulton Oursler, Jr., the magazine's managing editor, liked to exercise between a miniature orchard that appeared overnight on the grounds years earlier, full-grown and bearing fruit. God's little apple trees, one editor called the miraculous plantings, only one small corner of a glorious landscape with oaks and dogwoods and fields of blooms, a veritable Eden with eighty rolling acres of lawns, gardens and orchards. Another wag suggested that this paradise showed "what God could do if He had money."

It was an honor to be invited to join Oursler on his lunchtime walk. Since arriving I'd spent time with other occupants of Murderers' Row, where editors made final cuts to "thirty-one articles of enduring value and interest" that filled the magazine every month. Practiced hands like Roy Herbert, a nimble-witted poet who came directly to the Digest from Princeton twenty years before.

I recall Herbert bent over the desk in his office, editing a twenty-page manuscript. He sucked an empty pipe as he worked, a crutch against his cravings, battling an evil second only to communism in Digest demonology. Roy was condensing an art-of-living piece, Make Way for Minnows, delivering one masterstroke after another, casting out entire paragraphs, scattering minnows in every direction until twenty manuscript pages were reduced to three. "A nice little one-pager," Roy said and took a great pull on the pot-bellied briar.

The bells in the cupola were still ringing, when Fulton Oursler Jr. met me outside the entrance, wearing a pair of ancient plimsolls stained Reader's Digest world headquarters, with dirt. Before we took one step, a cigarette was in his mouth and he continued to chain-smoke as we roamed between God's little apple trees.

The good fight for a better, more beautiful America

"Tony," he was called to distinguish him from Fulton Oursler Sr., who'd been an editor and writer for the magazine in the 1940s. Tony's father reached Murderers' Row with blood on his hands having written About The Murder of the Clergyman's Mistress and seven other wildly popular detective novels under the pen name "Anthony Abbot

He battled his way up from Baltimore's slums as a reporter and became the right-hand of Bernarr Macfadden, an early twentieth-century health guru whose quest for "the most perfectly developed man in America" was the father of all bodybuilding contests.

Macfadden's Physical Culture magazine - Motto: "Weakness is a Crime; Don't Be a Criminal"-"Postpone Your Own Funeral" - read by hundreds of thousands of muscle-flexing males was launch-pad for a publishing empire that included True Story and True Romance and a newspaper, New York Evening Graphic.("I Murdered My Wife Because She Cooked Fish Balls for Dinner;" "Three Women Lashed in Nude Orgy!" "He Beat Me-I Love Him.")

With Macfadden's acquisition of Liberty, Fulton Sr. ran the third-biggest magazine in the country, the high-water mark of his editing career. Self-educated, his most profound learning experience was as a simple pilgrim in Palestine. Almost literally on the road to Damascus, Fulton Sr. had an epiphany that turned him from religious skeptic to a believer who found in the passion of Christ, his own lifework, The Greatest Story Ever Told. He wrote what he called "an elevator boy's life of Jesus," a popular telling of the story that sold millions of copies.

Tony was in his mid-forties and had the appearance of a well-scrubbed choirboy, despite the grimy shoes. There was zeal in Tony's dedication to the ideals of DeWitt Wallace and Lila Acheson Wallace, founders of Reader's Digest. Since 1922, when the first issue asked, "Can We Have A Beautiful Race?" - An article that agonized over ugly women in America, "especially the type built like draft horses and arriving in the millions at Ellis Island." - the Wallaces strove to make the world a better and more beautiful place.

Tony carried on the good fight, especially in thwarting communists, a Cold War editor whose writers cast a wide net for Soviet spies and plotters with the same ardor as Fulton Sr.'s Liberty men exposed Nazis in Brazil and Argentina.

As we walked between the apple trees, Tony quizzed me about Reds in South Africa. Was there a Party? Blacks? Whites? Was Moscow involved?

I said the Communist Party was banned in the early Fifties. The South African government severed ties with the U.S.S.R and kicked out the Russian embassy.

"Pretoria still sees a communist behind every bush. They blame Moscow for stirring up blacks across the continent."

"Is there going to be a revolution?"

For as long as I could remember, I said, there was talk of a bloodbath. It hadn't happened yet.

"What's preventing it?"

A simple answer was the might of South Africa's security forces, its army was the most powerful in Africa, its secret police the most dreaded.

"It's more than the iron fist," I added. "The Afrikaner believes apartheid is God's plan for South Africa. Go to any Dutch Reformed Church on a Sunday. You'll find it packed with worshippers. Their families have been in Africa for three hundred years. They rejoice in a promised land."

I sensed Tony's mounting interest as we roamed the orchard, where not long before a flock of local geese had come to forage on apples that fell from the trees. A Digest executive responsible for the grounds tore out of his office and rushed around pell-mell sending geese flying. Bird lovers on the staff expressed outrage at the man's attacks.

This inspired some editors to write a fictitious letter of complaint from a woman said to live at a pond where the geese made their home. "I was so mad at your Mr. So-and-So that I wished those birds would peck him on his you know what," said the dame. The missive ruffled the feathers of higher-ups who took pains to maintain pleasant relations with Digest neighbors. Down came an order that the geese were to be allowed as many apples as they were tempted to take. - Experience taught Tony to exchange his Florsheims for battered plimsolls before venturing between God's little apple trees.

Time passed quickly as I spoke about the history of the Afrikaners. Their forbears shared much in common with American pioneers. They trekked into the wilderness with their wagons, their guns and their Bibles, and a messianic faith in the destiny of their people. Again and again, their God forsook them and they were hammered in bloody battles with Xhosa and Zulu. They gathered the remnants of their volk and moved on until a day when they were victorious.

Their struggling republics were just getting on their feet when the Anglo-Boer War broke out. Their armies battled the British Empire to the bitter end and when all was lost their commandos stayed in the field, the first guerillas of modern time.

When our walk ended, Tony wanted to hear more about South Africa. "Let's have lunch next week."

Lunch at the Digest ran the full gamut from a dash for the cafeteria when the doors swung open at eleven-thirty to a command performance at the guest house, an eighteenth-century farmhouse beyond the orchard. A guest house lunch was no picnic, as I discovered years before when making my first visit to Pleasantville as an overseas editor.

I sat at a handsome Hepplewhite dining table with five senior Digesters, who quizzed me about everything under the African sun, an inquisition that lasted an hour with so many questions to answer I could eat but few mouthfuls and sip one drink. I'd been warned that asking for a refill was hazardous to the health of a fledgling editor.

If the guest house was booked, a Digester could take a visitor to the White Horse Tap Room or other local restaurant. I remember how surprised I was when first I stepped from broad daylight into the perpetual midnight of Mario's Trattoria, in the Seventies healthy living having yet to take its toll on the three-martini lunch. At Mario's or some such name, the décor was red plush, the walls rimmed with a trompe d'oeil of Roman urns and pilasters. Some patrons were already beginning to sip watered-down wine spritzers, but my Digest colleagues clung valiantly to their old habits. No sooner did we sink into the banquettes than our drinks came, Bloody Marys in goblets the size of flower vases.

I lunched with Tony at a Chinese restaurant in Mt. Kisco, sitting over a flaming hibachi heaped with egg rolls and chicken wings, spare ribs and pork strips. Tony was no stranger to the Café des Artistes and other glories of France in expense account Manhattan but confessed that he liked nothing better than to chew the fat over a pu-pu platter.

"The timing is perfect for a book on South Africa," he said immediately.

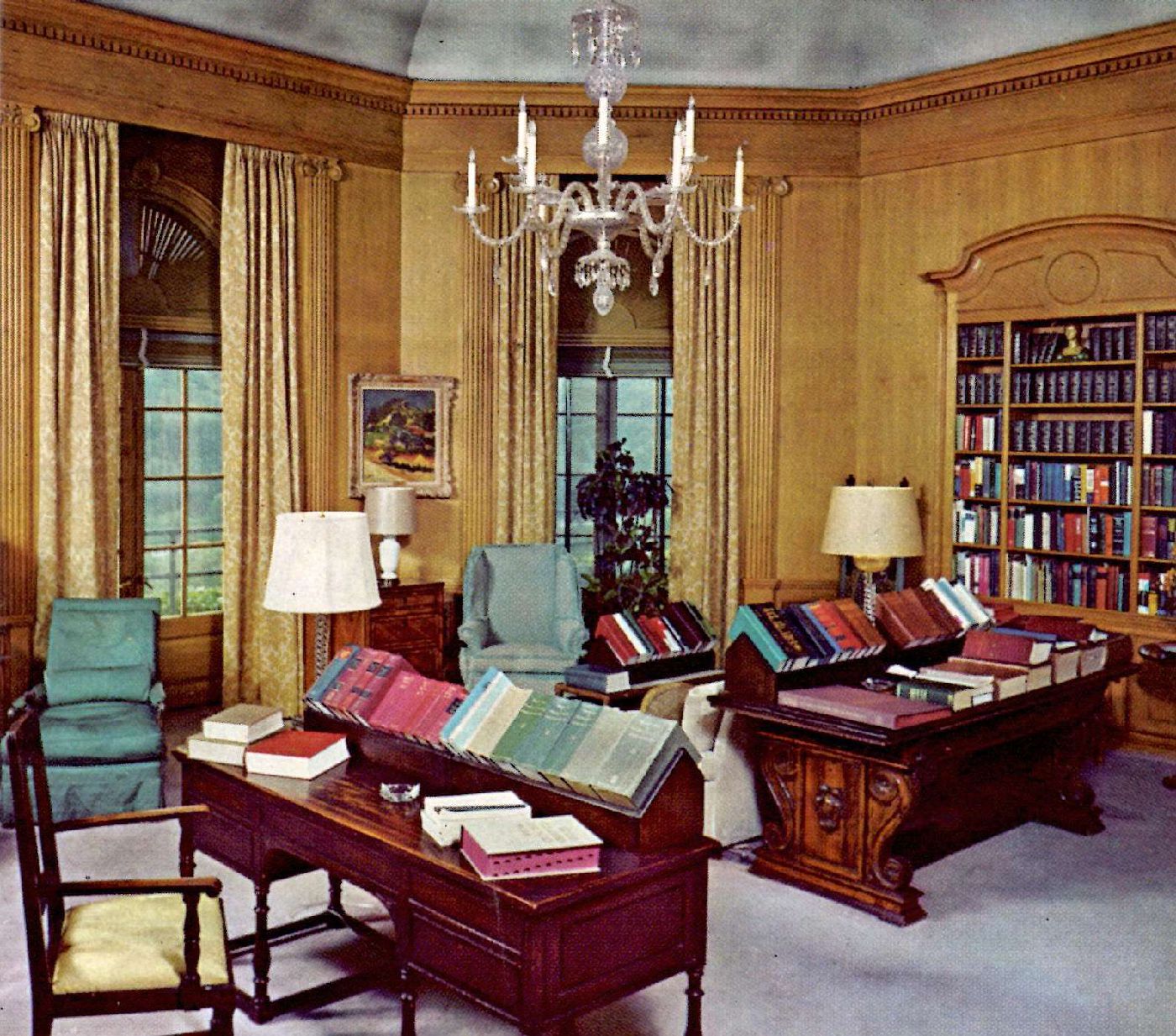

I couldn't agree more. I'd been brooding over a South African novel for a long time and had brought a bulging file of notes with me to America. In the months before leaving Cape Town, I haunted bookstores and scoured market stalls on the Grand Parade for hundreds of works. - The shelves in Michener's study at St. Michaels would come to be filled with this eclectic collection of Africana.

It was an exciting lunch as we tossed around ideas for a novel that would appeal to American readers. I saw a different Tony from the quintessential Digest man who would be keeper of the kingdom of DeWitt Wallace. He was after all the son of Anthony Abbot who weaved complex plots around his hero Thatcher Colt, police commissioner of New York City, a super sleuth hunting the villains who slew the Clergyman's Mistress. It wasn't beyond Fulton Oursler Sr. to bring a tribe of "Ubangis" from Darkest Africa to shed light on the evils men did in the heart of the Big Apple.

A sparkle came to Tony's eye as we spoke of diamonds and gold and thunder on the veld, and all the other possibilities we saw in the story of South Africa. There were man-apes and battles between Australopithecus and Pithecanthropus; Bushmen, Hottentots, Strandlopers and Bantu migrants; Phoenician voyagers, Arab slavers and Portuguese navigators; Dutch East India Company men, French Huguenots and English settlers; Griquas, Xhosas, Zulus and Matabele.

We began 65,000,000 years ago and moved through the eons when the living veld was still a paradise uninhabited by man, and on to the 1970s when time was running out for the white tribe of Africa.

How to tie all this together? The answer lay in the soft, waxy kimberlite, a blue-colored volcanic rock that flowed to the surface at the end of the Cretaceous period. Trapped in the kimberlitic pipes was the richest diamond ever found, which Tony and I called "Star of Man." From its creation to its discovery and sale - to the Shah of Iran! - the diamond served as link to stories of men and women whose lives were touched by the gem.

"I'll put my thoughts on paper," I told Tony. I leapt at the chance to begin work on a novel I'd been dreaming about for years, but there was a catch and I was aware of it.

The magazine hadn't brought me to America to write books. I was to experience life at the hub of the Digest universe. I was to know the agony of the ladies of "Laughter, the Best Medicine," their days spent delving through thousands of letters for one sweet bon mot. I would work in the New York aerie of the Digest's hawk-eyed fact-checkers. I was to hone my skills with the great pencil men of Pleasantville who could cut anything down to size, even the most holy of books in Christendom.

"Do all this, young man, and you'll be ready for the supreme test." I would serve as issue editor choosing the Table of Contents for eighteen million Americans who read the magazine every month. Win the hearts and minds of this vast multitude and I would be ready to take on the world. Literally, for I was being groomed for a role as an international editor, a post on which the sun never set with one hundred and seventy countries then penetrated by the Digest .

I used the working title The Star of Man and planned a novel with ten major characters linked to the diamond, their multi-generational story coming down through the ages to a dramatic finale with the sale of the precious stone at Christies in New York. I spent the Christmas holidays drafting an outline, which I readied early in the New Year and took to Tony. I went back to my office far down the corridor from Murderer's Row and eagerly awaited his reaction.

Tony liked my notes for the South African book.

"Who can we get to write this?"

When Tony asked this question, I remained mum. Like many journalists who would be authors, I had my share of unpublished manuscripts hammered out while working at newspaper jobs. I said nothing about my hopes of becoming a novelist knowing what the answer would be.

Instead I heard Tony say: "It's a subject that could interest Jim Michener."

Michener was among a galaxy of writers edited by Oursler, including Alex Haley, whose quest for Roots was backed by the Digest, Lowell Thomas, Theodore H. White, Henry Hurt, and Edward J. Epstein. Jim had been writing for the magazine since the early Fifties, handpicked by DeWitt Wallace who wanted him to join the staff. He opted to remain independent but contributed dozens of articles as a Digest roving editor and wrote several Digest-sponsored books. Tony was instrumental in Michener's Kent State, which investigated the May 1970 shootings at the university in Kent, Ohio.

Michener was seventy-one in April 1978 at the apex of a writing career that won him millions of readers worldwide. I'd run magazine articles by Jim in the Digest's South African edition and like millions had picked up his books. I'd read The Source, his novel about Israel, and his American epic, Centennial.

I found The Source a marvelous book. I especially admired the way Michener unfolded a story of biblical proportions, layer by layer as his fictional archaeologists excavated Tell Makor in the Holy Land. The dig provides the structure and timeline from Level I that yields a bullet fired from a British rifle around 1950 to Level XV where twelve thousand years earlier the son of Ur the hunter fashions the first sickle with five flints wedged in a curved bone, four of the razor-sharp stones found at Tell Makor.

It was mid-March before Tony sat down with Michener and broached the idea of a South African book. They met in New York, where Jim and his editors at Random House were correcting final proofs for Chesapeake. Tony told Michener how our idea for The Star of Man was born and offered some background about me.

I can picture Jim studying Tony as he spoke, an expression I would often see, a far, far away look that told you the mills of James A. Michener's mind were grinding away, stripping the waste, sifting the detritus, picking out the lodestone.

"I've been thinking casually about such a project for several years," Michener said. "I'd like to meet your man and learn what's on his mind."