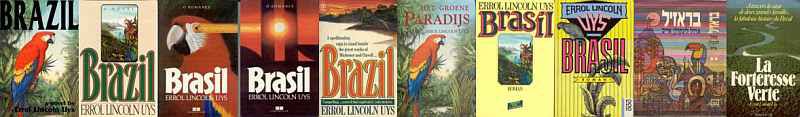

In his review of Brazil, Professor Wilson Martins compares my novel with the works of major Brazilian authors including Jorge Amado, João Ubaldo Ribeiro, José de Alencar, and asks what “mysterious and complex circumstances” allowed a foreigner to overcome obstacles Brazilian writers had barely managed to confront: “Uys is the first with the talent and sympathy to understand Brazil as an imaginary creation, coherent in its apparent incoherencies, organic in its historic development, complimentary in its contradictions and antagonisms, unitary in its differences and obscurely answering to the 'will of being a nation.'”

After a year on the move in Portugal and Brazil, I returned to the United States to begin writing. In November 1981, I made a dismal entry in the back of my Brazil travel journal:

November 24,1981: Exactly one month since my last entry so far away in Brazil. Try as I will, I cannot get this “breathless task,” as someone called it, properly underway. I look for the faintest excuse to postpone that release of imagination, the “fire” that will send me racing through ideas and pages.

Painfully producing Page One and going over it again and again, convinced that it does or says little. Slowing down one's mental process so that thousands of pages of crammed reading — my main work activity thus far — becomes a jumble of information unrelated to the task at hand. All the time hoping that some “miracle” will suddenly breach these dammed-up emotions.Asking myself whether this is normal adjustment process or signpost to self-willed disaster. Praying that as I pen these words I may through this self-appraisal, this mirroring, look at myself and find a way out of “writer's block.“ — As I write this, I begin to see how foolish it is: why not spend these words on the manuscript?

Another entry, two weeks later:

December 8,1981: Still struggling to light the fire! Filled with unreasonable fears and doubts, and elements of self-destruction! God knows but here I am, with everything I've ever asked for and with nothing to stop me, and I am fooling around as never before. What do I expect? That I'll awake, miraculously, one morning and find the whole book imprinted on my mind? I write paragraph after paragraph turning each one out with great pain, and rejecting it all as inadequate! I have to take hold of myself or the result will be disastrous! Courage! What a word! Courage!

Then, a third and final entry:

March 1,1982: Have just re-read all journal entries in preparation for Block Two of book, after finishing first three chapters of 50,000 words!

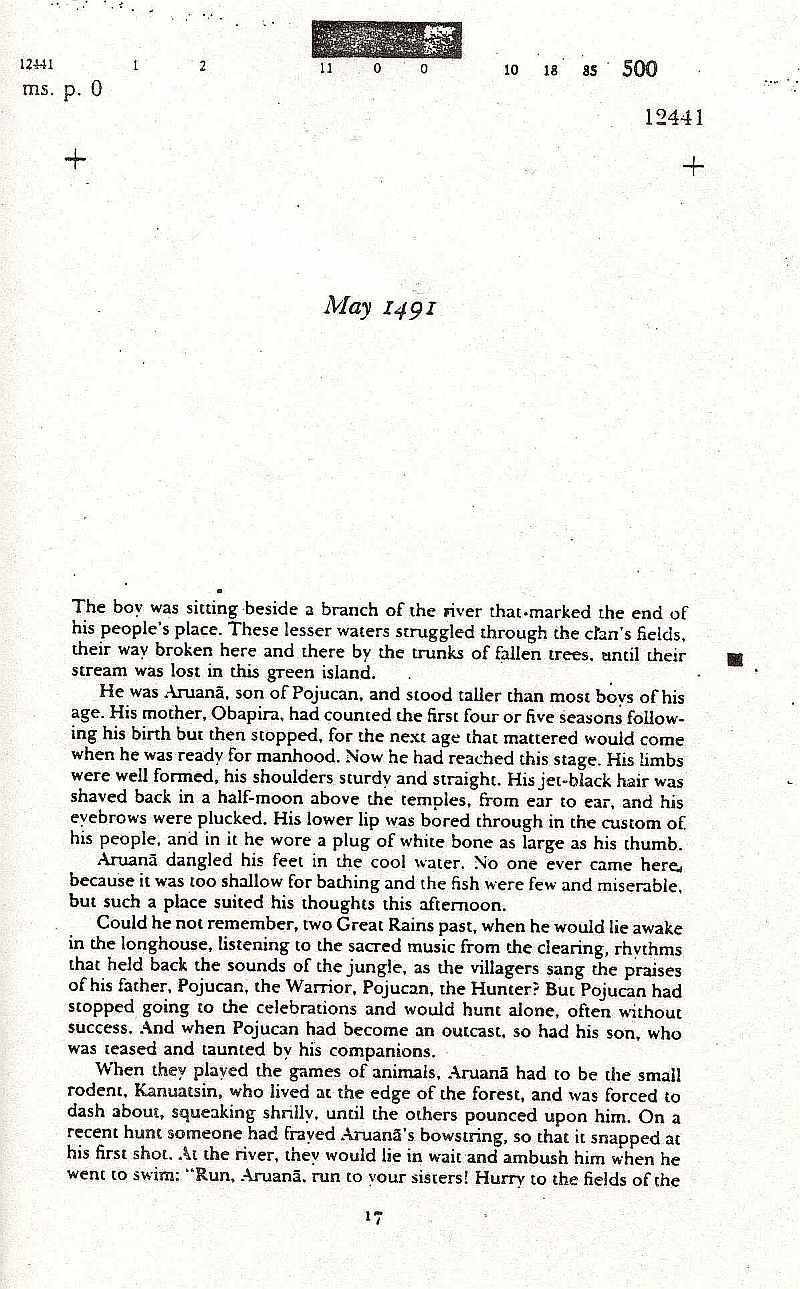

In early March, my outline and three chapters with the story of Aruanã, the Tupiniquin, went to John Cushman, my New York agent. The following month, Herman Gollob of Simon and Schuster bought Brazil with an advance of $45,000, a respectable sum for a first-time novelist. Herman edited the works of James Clavell (Shogun, Tai-Pan) and was editorial director of the Literary Guild book-club which bought The Covenant by James Michener eighteen months earlier. No stranger to the epic novel, even Herman couldn't have imagined the stupendous voyage we would take together on the river sea and across the sertão of Brazil!

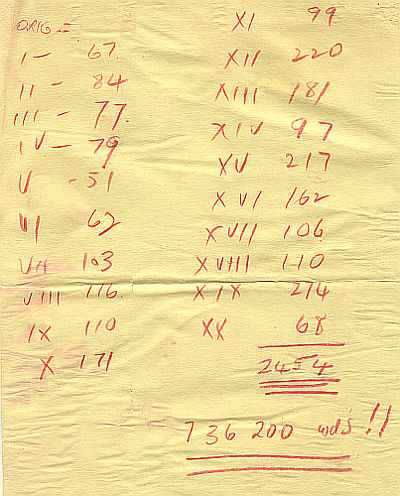

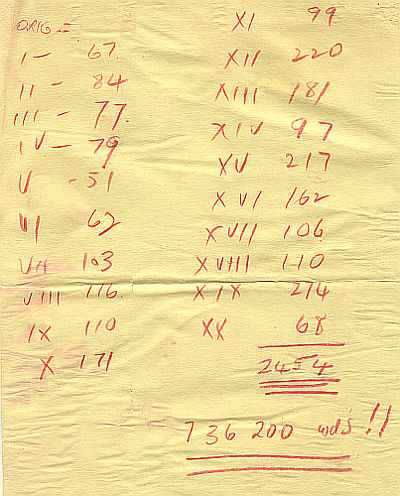

I made this note when I finished the final typed draft of Brazil: 2454 hand-written manuscript pages with 736,200 words!

Five years after beginning work on the novel, Herman and I sat down to make the deep cuts needed to trim the book to the one thousand pages published in the First Edition. (In 2000, I made further edits for the New Revised Edition, while adding an Afterword bringing the story up to April 2000 when Brazil held its quincentennial celebrations.)

The road to the three-quarter of a million words was as challenging as the indomitable path that carried my bandeirante Amador Flôres da Silva and his artist companion, Segge Proot, pupil of Rembrandt van Rijn, on their mighty journey through the Brazilian wilderness in quest of El Dorado.

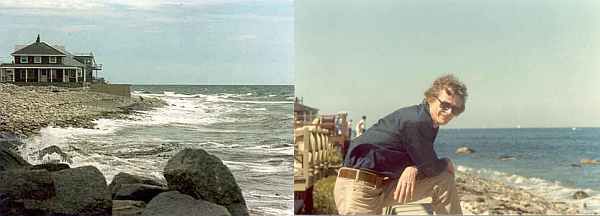

I followed one simple work routine from my days with James Michener. I was at my desk and working by eight-thirty every morning and kept at it until six in the evenings, nine hours a day, six days a week. My office was ten feet from the Atlantic in the small Massachusetts harbor town of Scituate.

I had few visitors who didn't remark on how inspiring I must find the ocean view, but in reality my desk faced away from the sea. Sometimes though, the scene burst upon my imagination as when Hurricane Gloria slammed the New England coast and tore away at the house sending a wall of water cascading past the windows. Definitely, an inspiration:

It had come with little warning, a great deluge out of the south. Waves rose to the heavens, monstrous in size and shape and sheer power: winds howled past bare poles and whined in the rigging like the demented calls of the Sirens.

For three days and three nights, São Gabriel was buffeted without letup. Marinheiros clawed their way along the deck to the steerage, where Padre Miguel cowered, and went on their knees before him seeking his blessing for they did not expect to survive this sea. The padre was like a broken reed, but he found strength to call these men to account for their sins.

Cavalcanti sent men below to find the most serious leaks, and when they returned sodden and shivering, their report was dire: The ship was open at the stem, so that when she pitched, the timbers crashed together and a stream of water rushed in. Day merged into night as the crew kept the pumps going and struggled with the bailing tubs. Ropes tied about their bodies to prevent them from being swept off the deck bit into their flesh till the skin was raw and bloodied.

Three men at the helm cried out as they strained with the tiller. All eyes were on São Gabriel's mainmast, where already the yard had cracked with a tremendous noise and hung at a precarious angle. In the hold, men did all they could to stop the leak toward the bow. Cavalcanti himself was among them, waist deep in the chill water that flowed with the rot and filth clogging her bottom.

On the morning of the third day, the wind lessened enough to allow the men to fasten a sail under the prow and to repair a pump that had broken during the night. For the first time since the storm roared up, the level of the water below beck began to fall.

The final rage of the dying storm exploded against them during the night, and water poured in again, from above and below. Two Marinheiros were lost in the black, blind tempest, hurled off the forecastle by a cataract that burst across the deck as they fought to secure a loose stay.

From the outset, I was conscious of a presumptuousness in seeking the past of a people to whom I was a stranger. I wanted to do justice to Brazil's history in a novel that was neither simplistic nor intellectually dishonest in catering to outsiders' fantasies about Brazil. So, although I had my outline and research from my trip and had read widely, with each new section of the book I looked at the subject with totally fresh eyes and in much more depth.

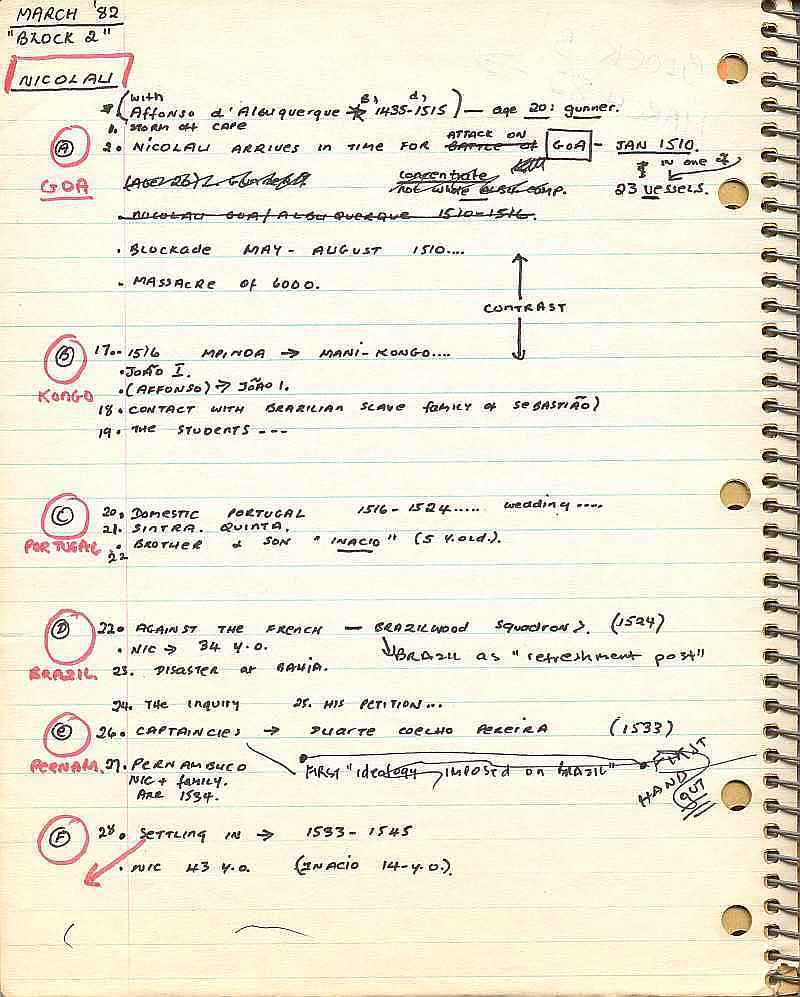

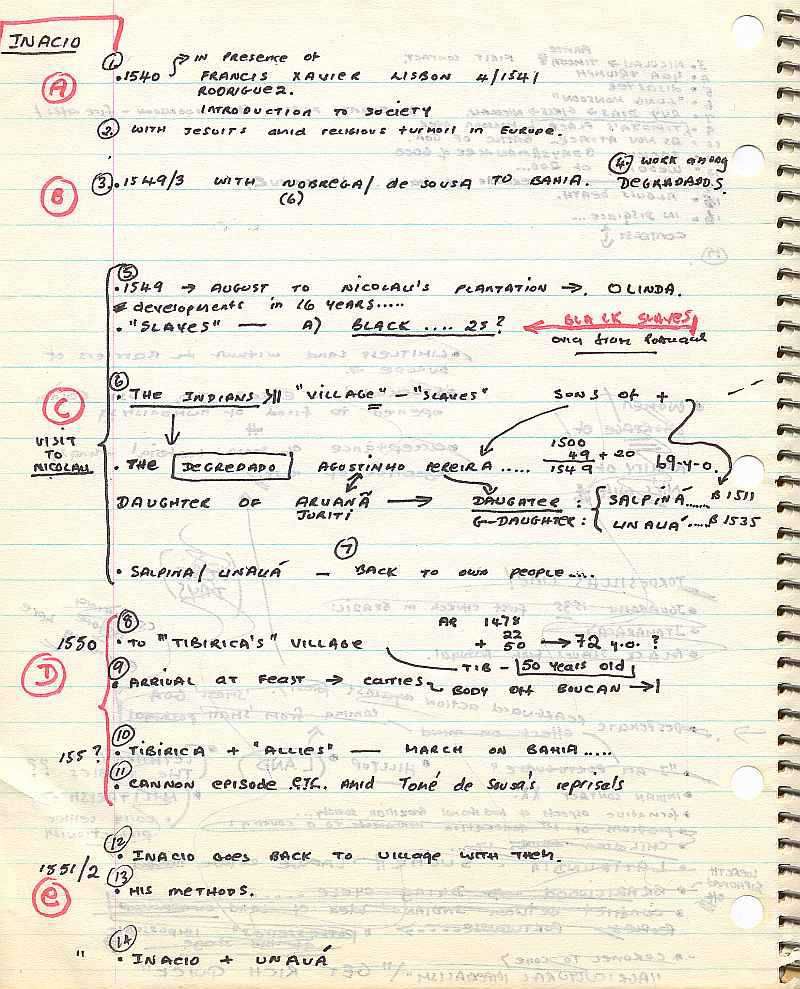

Three examples of this preliminary work in writing historical fiction follow, all done in a day before personal computers simplified such note-taking, sorting and filing:

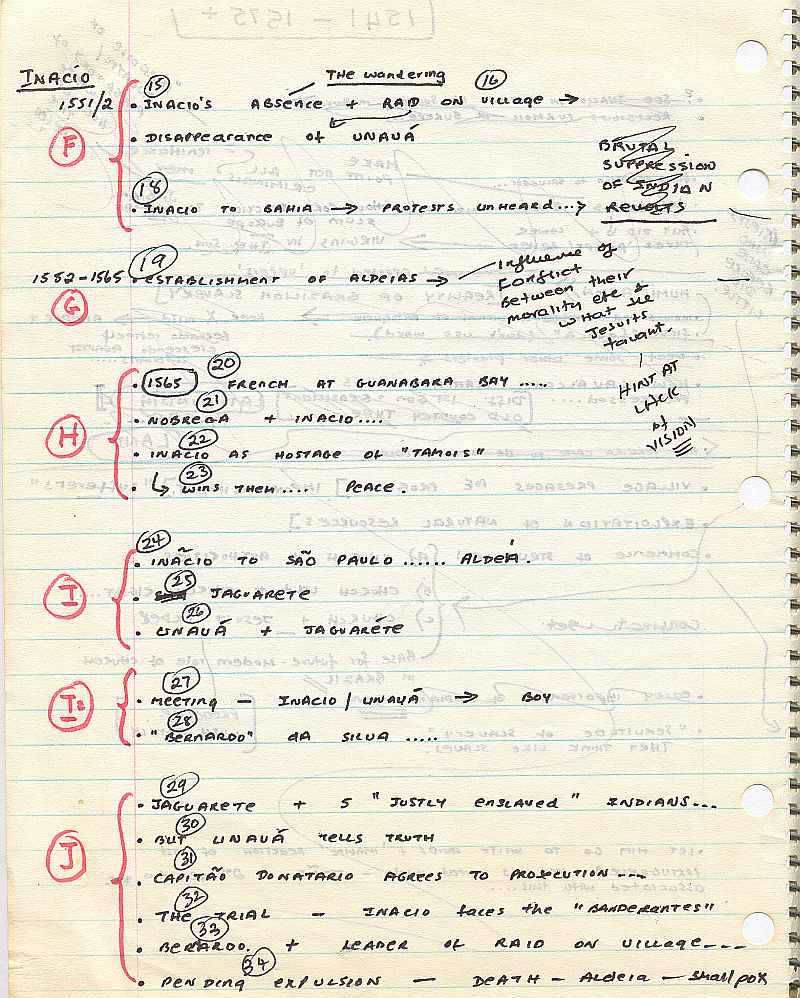

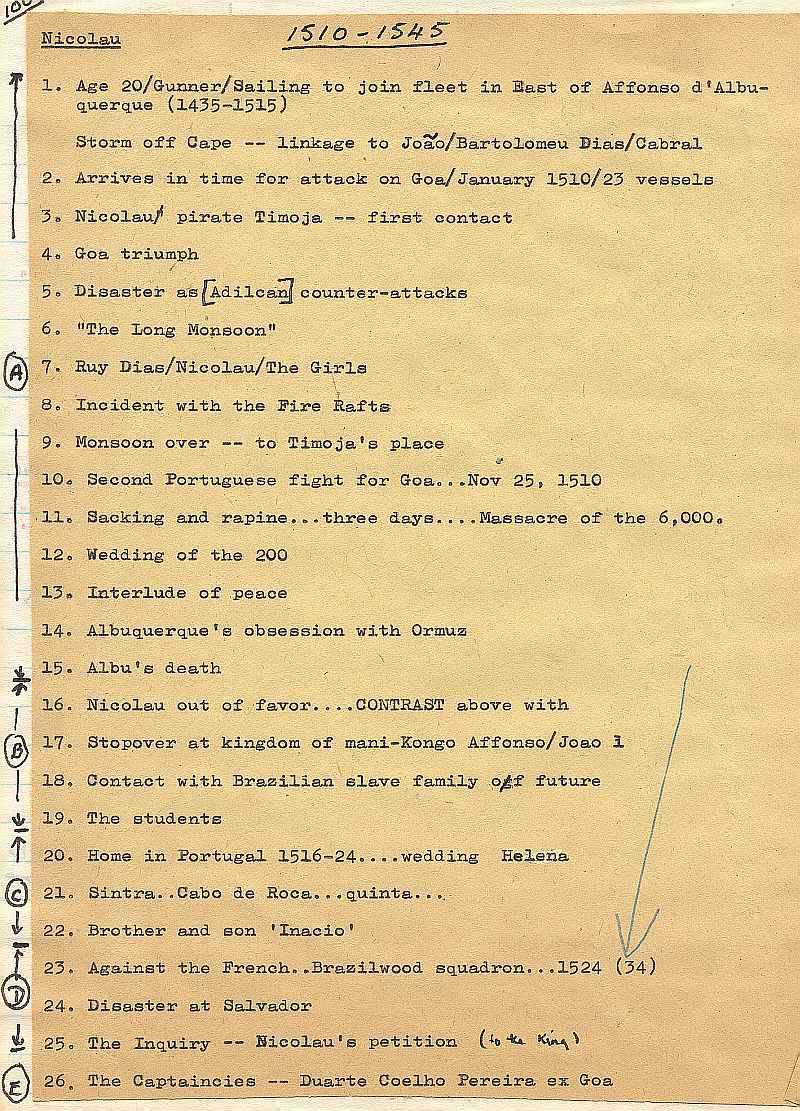

Inácio Cavalcanti, padre, Society of Jesus, with Nobrega to Salvador, Bahia, then to uncle Nicolau, Olinda, with degredado Affonso Ribeira, Indian village of Tiberica, the aldeia, the expulsion, 1541-1575.

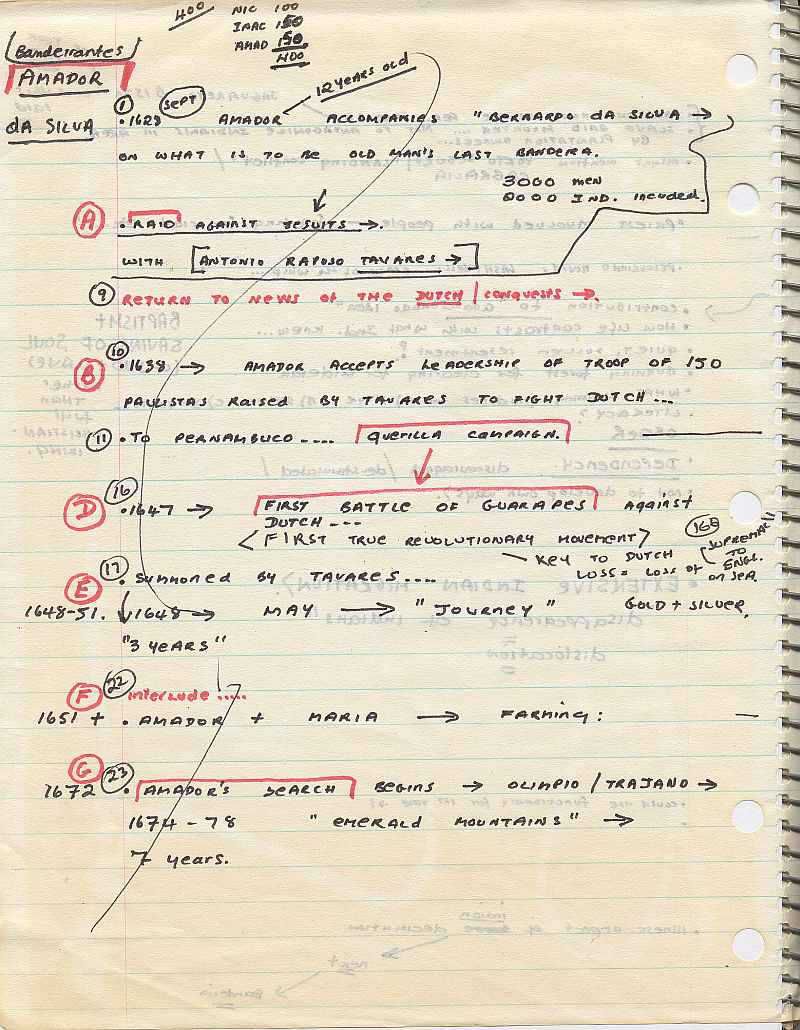

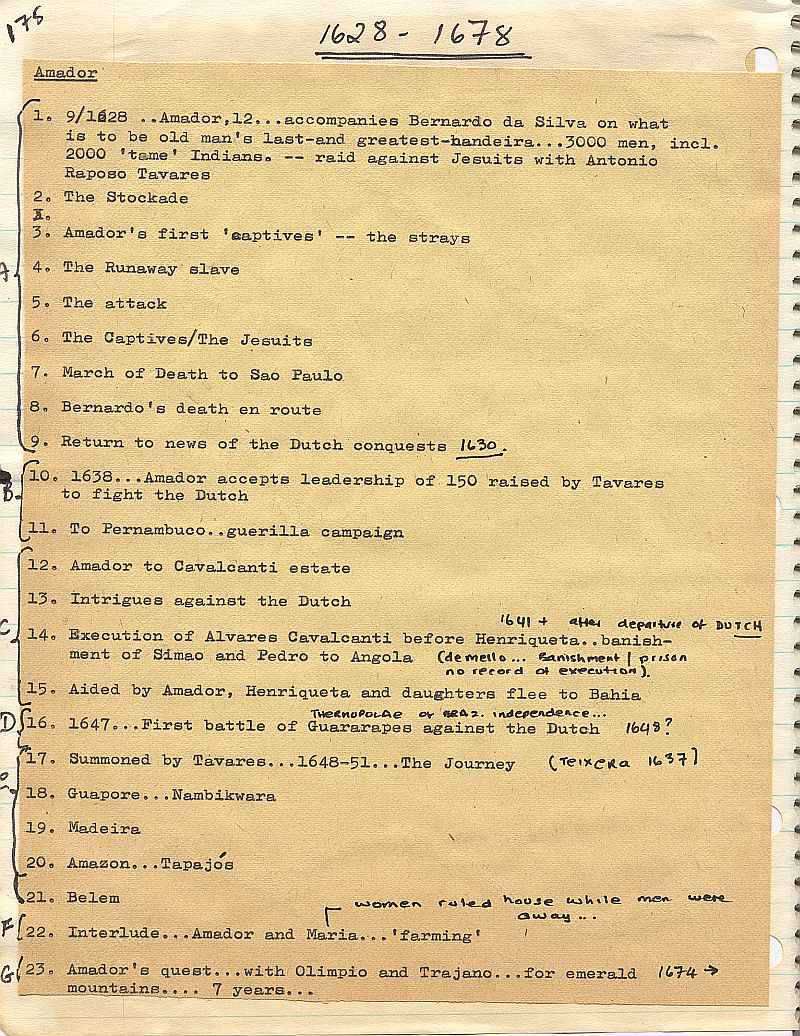

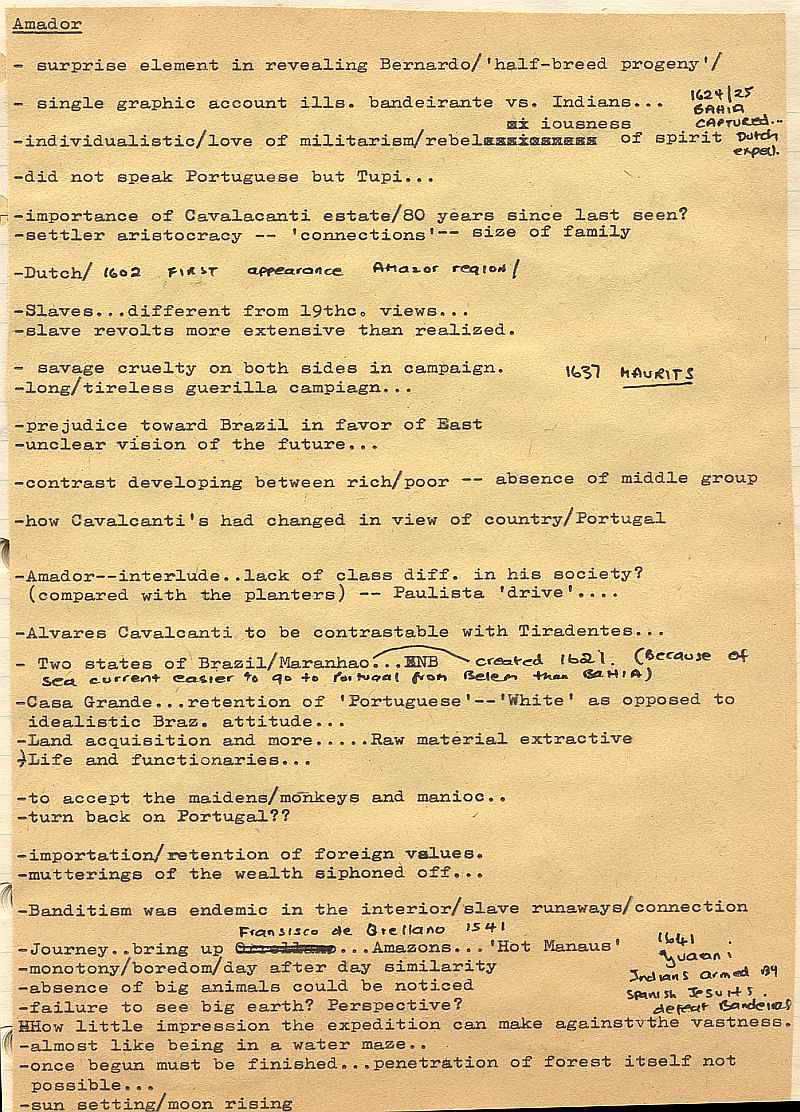

Amador Flôres da Silva, bandeirante, raids against Jesuits of Paraguay, Pernambuco, Guarapes, quilombo, Ganga Zumba, Joanna Cavalcanti, Segge Proot, Madeira-Mamore, Amazon, Emerald Mountain, 1628-1678

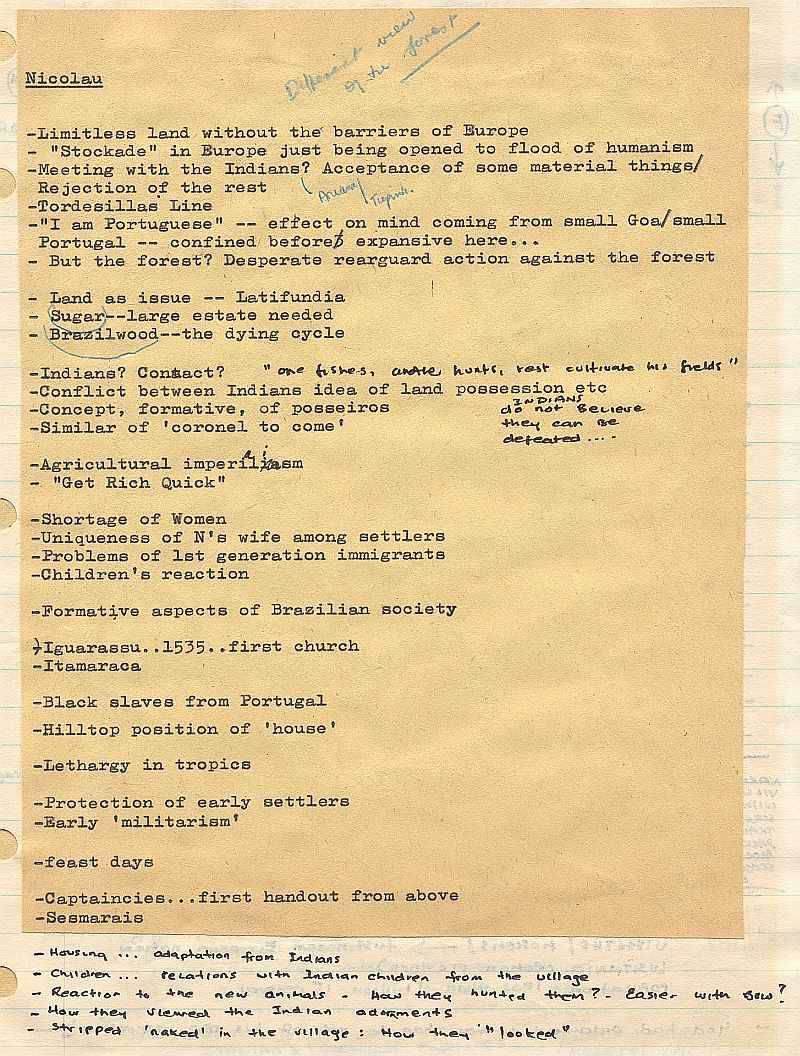

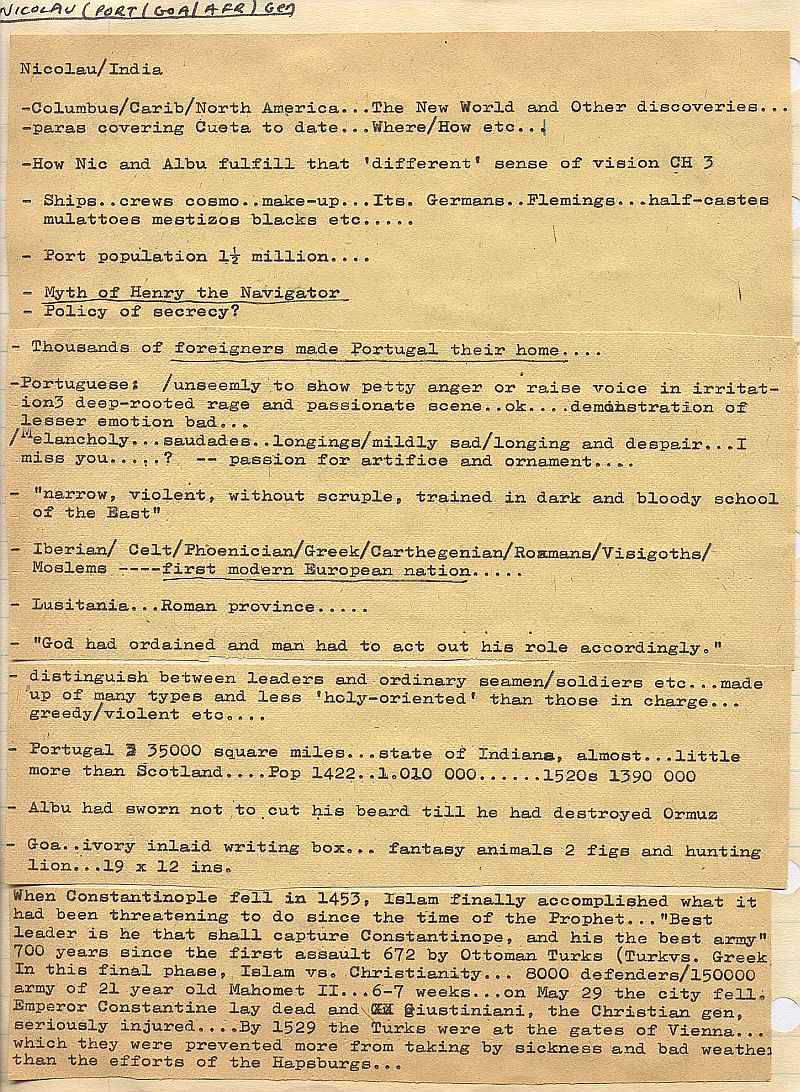

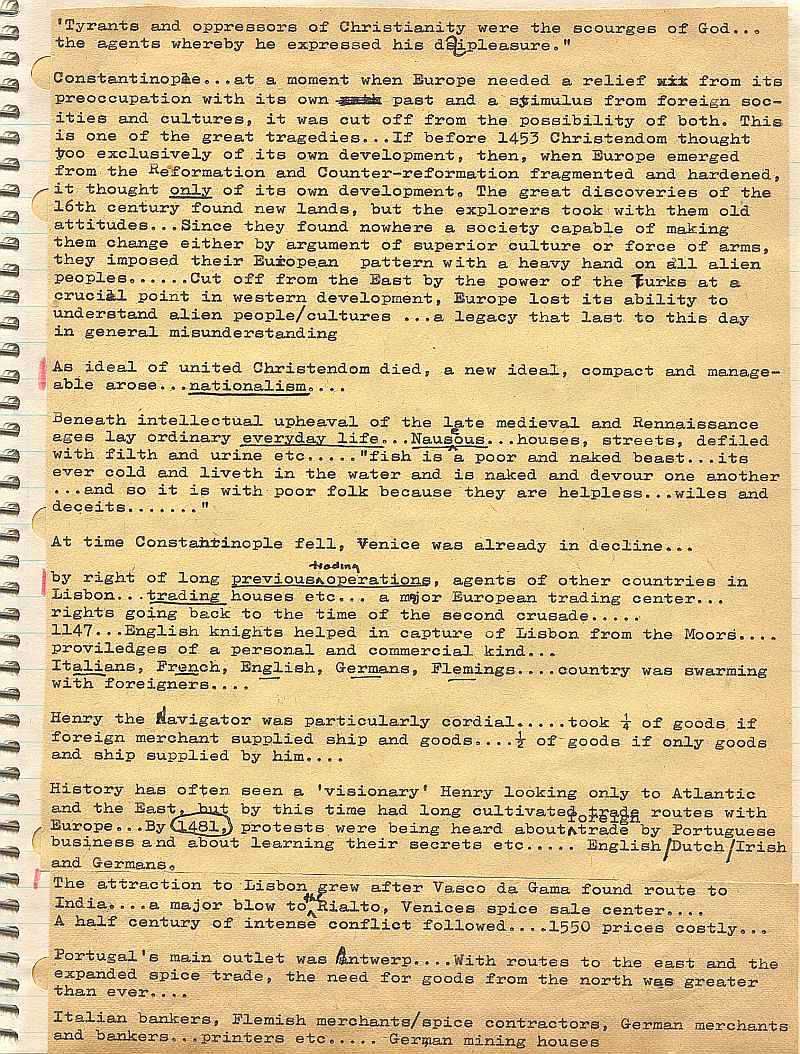

Alongside my expanded plotting, I focused on specific reading for each character's background, settings and action. With Nicolau, for instance, these areas included Brazil prior to formal settlement, Portugal, Goa and Africa. One of the backgrounders for Amador Flôres da Silva dealt with the “sixty years captivity” of Portugal by Spain, which had a profound affect on the thinking of the bandeirantes and their territorial drives. The following are typical of the notes I kept as I read my way into these subjects.

The upshot of this prodigious work was that when I sat down to write a section, I'd looked at my subject from every angle. Much of what I needed was locked into memory. With little call to go back to my reference works, I could concentrate on telling the story, which after all was the essence of the novel.

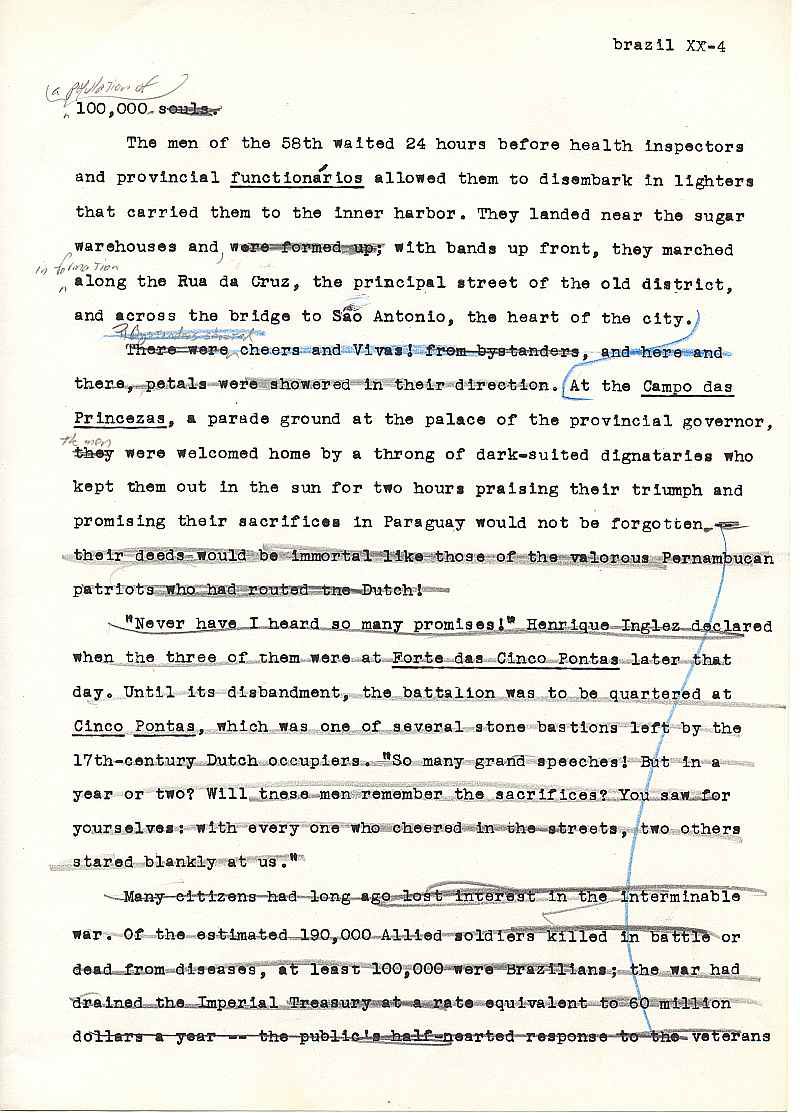

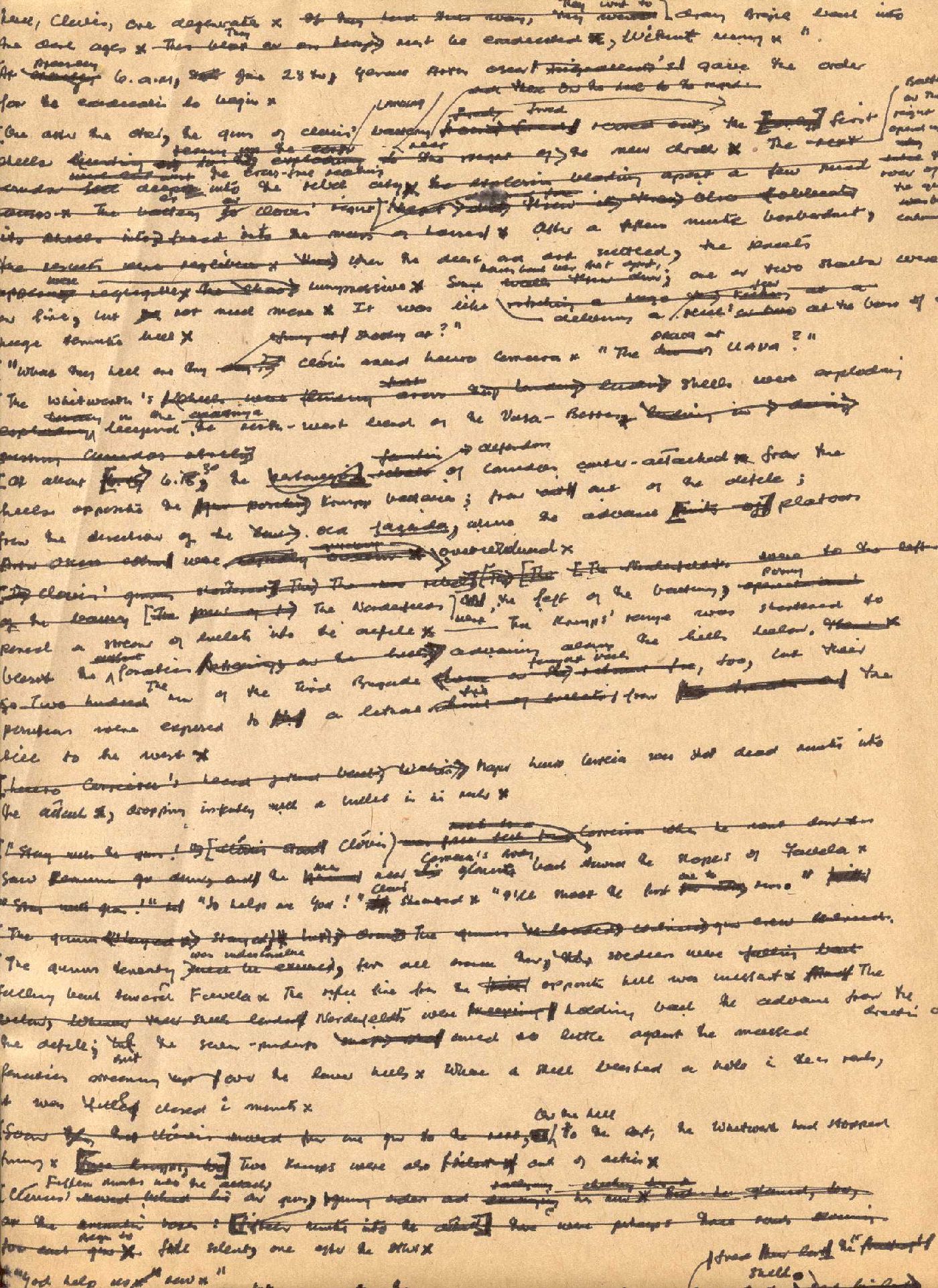

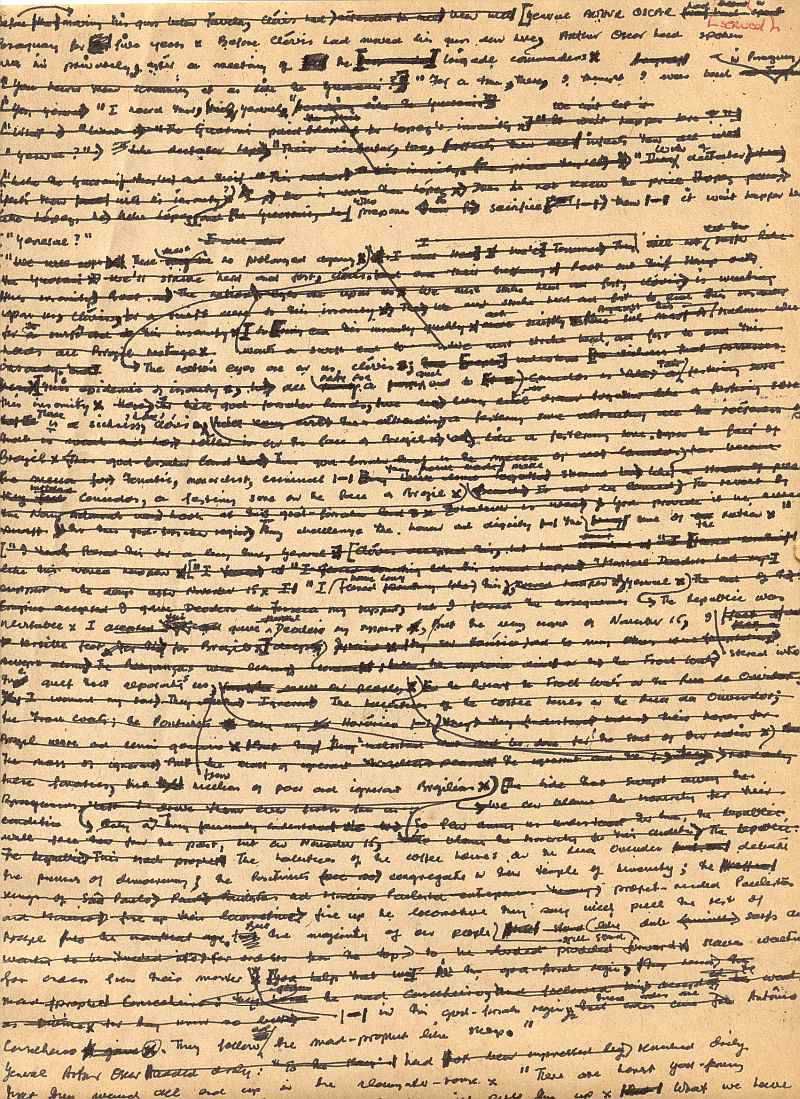

I wrote the original manuscript in long-hand. “Hieroglyphics,” people have called the pages I turned out, for good reason as these examples show. I fell into the habit of this microscopic penmanship with a particular brand of roller pen (BIC, black-ink, medium.) Not only this but I kept track of the pens I used over four years! 154!

A trivial amusement as I wrote my way through twenty-two huge blocks of narrative, the smallest fifty one manuscript pages, the largest almost three hundred pages. The latter covered the Paraguayan War and took six months to write, a totally draining experience for the horror I encountered in this forgotten tragedy that saw nine of every ten Paraguayan males, adult and child, slain on the battlefield, the greatest war between nations in the Americas.

Written on tablet-size blocks of newsprint, I wrote two to three of these pages each day. Another daily habit was to begin each day's writing period by numbering my pages 1, 2, rarely 3, making a potential nightmare for anyone seeking to collate the manuscript.

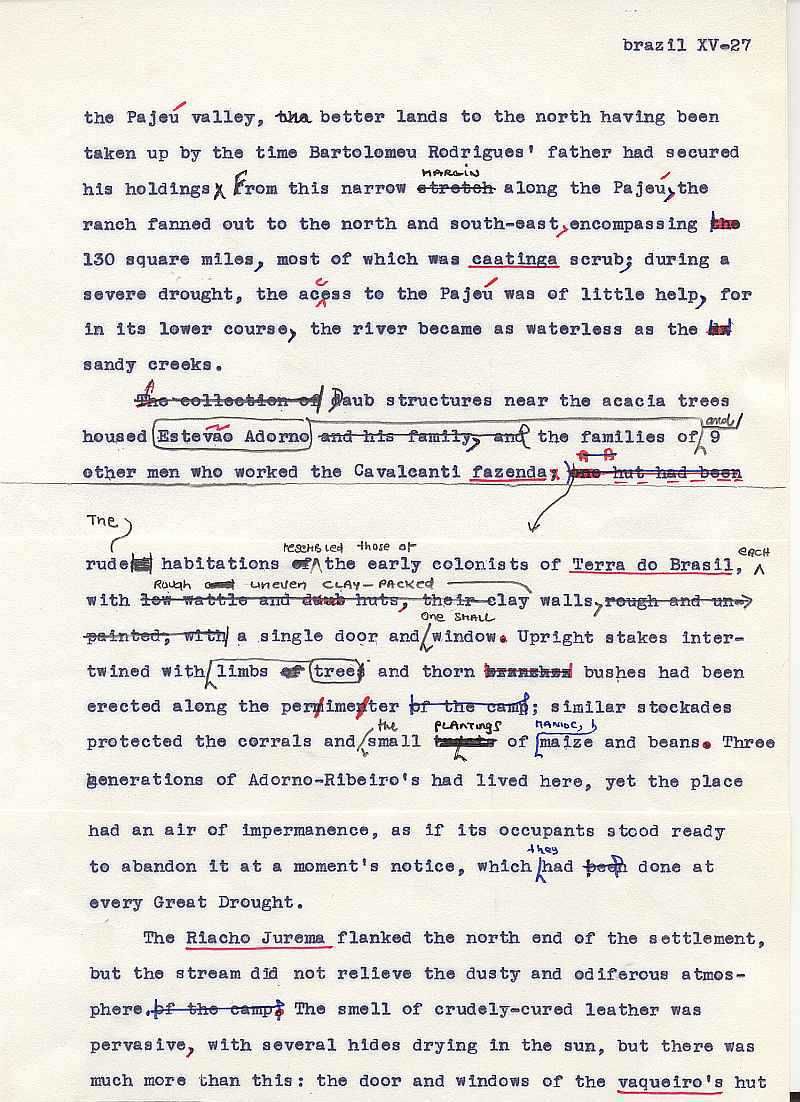

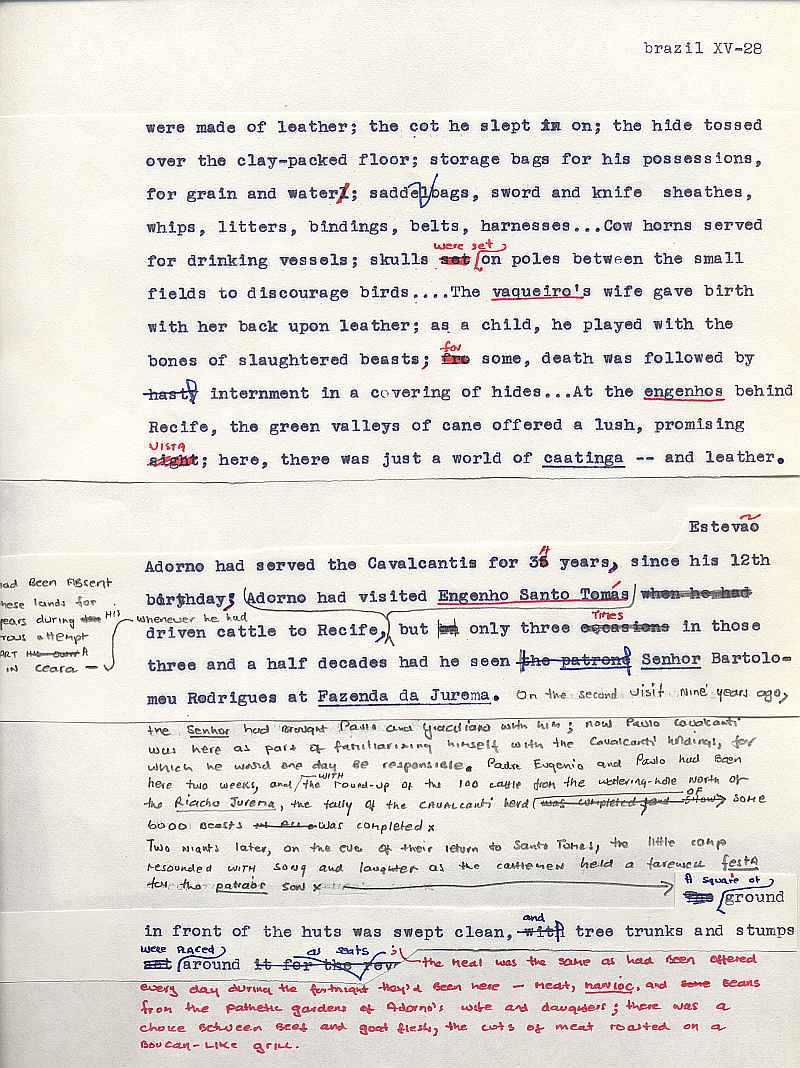

I would finish around five in the afternoon, then type up these handwritten pages. Soon after beginning to write, I bought a sturdy 1930s Royal typewriter on a yard sale for $1, a formidable machine heavy as iron and loud as a cannon. Every afternoon, I typed my second draft on this beloved monster pounding the keys so that the entire house shook.

I re-typed my edited second draft for submission to Herman Gollob at Simon and Schuster. This draft was sent in eight stages comprising the Six Books, Prologue and Epilogue that make up Brazil.

The indefatigable Gollob armed himself with black and blue pencil and cut deeply to produce the fourth draft. When the final deadline approached, we still needed to drop four hundred or so pages. We did these final cuts together over a two week period at Scituate. At last, the fifth and final draft went to the printer for proofing.