Porto Velho, Rondônia, August 24 — September 1

August 24-25 Several letters awaiting me, Fulton Oursler among them. Fulton notes: “Why you put the shackles on make damn sure you have the key!”

A crucial poser! Have given it much thought already Don't know full answer but what comes to mind: Land. Dimension. Diversity. Possession. All these are key to understanding Brazil.

The very first impact on Portuguese must have been staggering. Coming from tiny Portugal, the men of Lisbon confine their territories to small bases hugging the littoral, same as in Africa and the Indies. Their motives are primarily exploitative, “factories” for securing wealth, trade for the motherland.

European man emerging from the Middle Ages, not thinking of “land” beyond concept of age-old fiefdom, small kingdoms, encounters a new world of a dimension not previously imaginable. What an impact this must have had on his mind, his view of earth, even of the universe... But could he cope with this change?

First, in Brazil, he seeks the simplest solution, the neat and totally impractical division of “captaincies” stretching as far inland as the Tordesillas Line; the captaincies themselves being divided into sesmarias. For two hundred years, he hugs the littoral, fearful of what lay beyond and lacking the ability or manpower to penetrate the interior.

Essential to show difference between American homesteading and planned advance to the West and Brazilian method which to this day suggests unplanned chaos. What factors led to different development? The men, their background, their religion? The climate, the topography? All these factors have to be considered?

Did the Portuguese — despite what Freyre says about creation of a Luso-Tropical “new man” — transfer some of the worst elements of Middle-Age Europe to South America?

For example, the concept of nobles and serfs, here becoming casa grande and senzala (slave quarters,) fazendeiro and laborer. As before, the few held vast estates to which the many were bound for their livelihood. Unlike North America where whole concept, once they'd thrown off the European yolk, was toward the individual, his freedom and a stake in the land. Nothing like that ever happened here. On the contrary, in the 19th century the Portuguese Crown was able to transplant itself to Brazil and extend the age-old system almost to the 20th century.

Perhaps Brazil only achieved its equivalent of the U.S. Declaration of Independence in 1930 with Vargas 154 years later. So that in a sense, it is today where the U.S. was fifty years after independence, mais o menos, with emphasis on spiritual and national development rather than material. The latter with 'secondary acquisition of developed technology' can be deceptive.

With what you see and hear in the North/ North-East, the greater part of Brazilian 'land,' you come to realize the divergence between north/ south. Whether it's Pumaty's casa grande owner or a local laborer, all decry the south for bleeding the north to develop its industries etc. If you accept that then you begin to think of Brazil as a funnel, the north the mouth, the south the thin stem to which all filters down. (But no doubt the South will have its opinion - probably on the vast cost of supporting the North and its “hopelessness.”)

More on land debate: Perhaps nowhere has “colonial” man faced so great a challenge as in Brazil and, perhaps, Siberia — the sheer vastness makes one of the essentials for development infrastructure i.e. communication, well nigh impossible.

Traveling from Manaus to Porto Velho again underlined the poor attempt at “conquering” the forest — the pathetic little farms alongside the road, the road itself, tarred but in a state of disrepair. Almost like traveling on a dirt road, the bus swerving from one side to the other to avoid potholes and sections of the road that have completely degraded. Atmosphere is pioneer, perhaps no better typified as in roadside “restaurants” - crude, wooden affairs catering to buses and truckers, serving one or two dishes only, great piles of food, rice, spaghetti, farina, chicken or beef, and stocked with only bare essentials.

Found sight of smoldering embers of destroyed forest beside road disturbing; nothing seen thusfar has convinced me settlers know what they're doing.

As one informant said: they clear thousands of hectares adjoining the rain forest for cacão plantation and introduce cacão trees. What they ignore is forest's own defense mechanism: Will it introduce new species of insect or disease to fight this invasion of its territory? I like this concept of forest as a separate, living entity existing by and for itself, something surrealistic, but need to see it as such to reflect on its relationship with man.

In a small town like Porto Velho, you cannot help noticing excessive number of government organizations. In the downtown area virtually every street has its EMBRATEL, INCRA, INDECO, SUDENE etc - endless offices of functionaries all aiming at one or another type of disinvolvemente. (A strange word to my ears, for translated it means development; having seen some of these functionaries in action you wonder just how much "disinvolvement" gets done.)

At last, the Madeira-Mamoré railroad. Strange feeling of unreality today accentuated by sight of swimming pool, good food (!) and out in Porto Velho's blazing hot rail yard: abandoned engines and rail construction equipment, birds nesting in a great steam powered crane that once moved along the newly-laid rails.

As in Recife, Belém, Manaus, much of the historical atmosphere has been destroyed. It takes a special effort of imagination to recapture what it must've been like - to envisage it in the days of Vicente Cardoso (Cavalcanti.) Feel especially confident of Vicente as character and almost capable of writing about him now.

August 26 On this writing table a few inches away is a souvenir of the Madeira-Mamoré railroad. A six-inch spike I picked up yesterday. It evokes so much for me. It was here, in this very place that men came from all over the world to build this railroad and left 7,000 of their number dead.

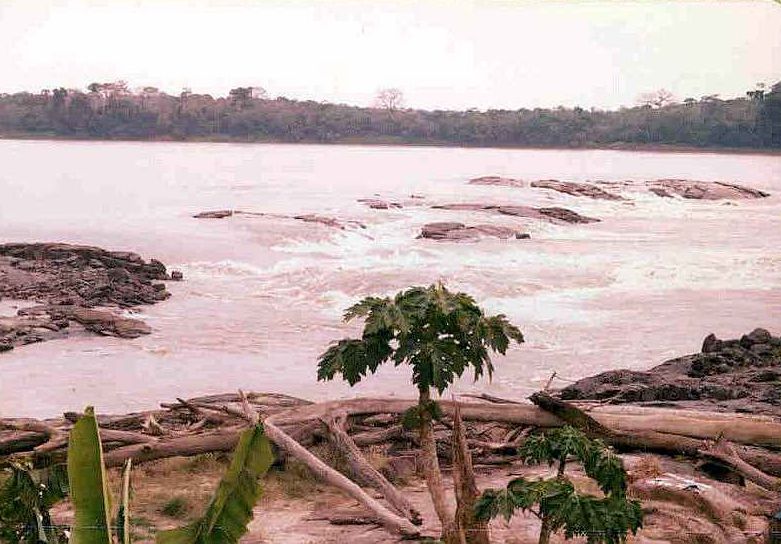

A war against The Forest, and which almost as it ended in 1912 was lost. With the collapse of the rubber boom the purpose of the railroad (to get Bolivian rubber to the “navigable” Madeira) no longer existed.

Today there is an attempt to re-activate the railroad, some 32 of 360 miles operative, but the real story lies in the marshaling yards where half a dozen old locomotives (Baldwins etc.) stand with their great steel wheels buried in the sand. Most dramatic relic is the steam-powered crane (INDUSTRIAL WORKS - BAY - MICHIGAN) that appears at the head of the rail-advance in old photographs. You can imagine it, easily, clanking and hissing. You can imagine it but you can't ignore the twitter of the birds amid its workings.

August 27 Above all, I have to remember to divorce present “reality” from historical fact: that the cemetery where hundreds upon hundreds - thousands - who labored to build the railroad lie is unreachable must say something. Can't go there, you're told by local head of museum, because bush that obscures place is infested with “cobras.” So, too, I think are the minds of those who inherited the sweat, the sadness, the lost dreams of all who came here. Nothing. Not a memorial, not a single relic except a small station filled with “functionaries” unexcited and unmoved by what they represent.

By God! I say to myself, I'll write an epitaph for you yet, you brave “lost” adventurous souls who lie beneath this dust-damned soil. You came from so far away to so violent an environment, and you found the paradise you sought an earthly hell!

I walk through these dreary streets, I witness this museum without a soul and I feel a rage and anger beyond my control at such forgetfulness, such disregard for heart and soul and effort.

I look at a single spike, a single spar of rail, a rusted locomotive and I have respect. For what am I but an adventurer braving the same area, but with a comfort and safety you never knew. For five days I have trod these same grounds, endured the same heat - with air conditioning to help - and yet at no time have I seen anything that said these were men! — How I hate the forgetful, the thoughtlessness!

How I sometimes love the adage, "those who forget the lessons of the past are bound to repeat them." I wouldn't really wish it upon them but if they are so ready to dismiss the 6,000 (10,000?) who gave their lives in this place...

I enjoy this burst of emotion, for it gives me a special urge to reach paper, it puts six thousand spirits behind me saying, "Tell them!" It brings a single spirit, a soul perhaps akin my own, who lies a dying in Candelaria with thought of a love far away, feeling all forgotten forever — I say to that spirit bound to this dusty hell hole, you will be remembered, not alone in dry unemotive reports I spent the best part of a day reading.

I sometimes begin to feel like Lord Byron and Childe Harold: “God, why did you give these people this land?” Oursler said I had to have a key. Well, tonight, amid this searching of soul — admittedly without intellectual censorship as the good Antonietta would have it — I'm hyper-critical of the Brazilians. They were handed one of God's private reserves. Are they in the process of screwing it up?

God, how I need a Sintra! How I need some cool, refreshing place where I can breathe “fresh air,” “sanity” and begin to believe! But then, I tell myself, how can you write about Brazil without experiencing all of it? Even the most distressing aspects? And what is better than spending so much time in the North/North-east until you begin to cry inwardly, “Away!”

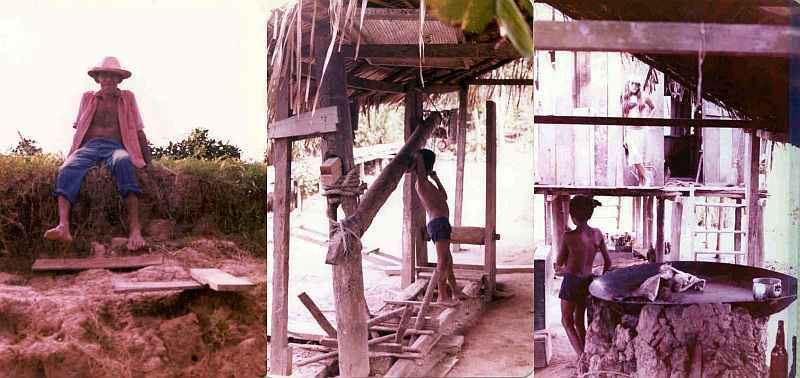

August 29-30 Left Porto Velho at 4.30 a.m. with Eduardo Borcacov for Guajará Mirim 335 dusty kilometers away. Argentinean-born Borcacov of Russian heritage converses on virtually any topic under the sun with worthwhile opinions. He knows environment intimately from many years in Rondônia's forests as lumberman. Trip took ten hours driving with two hours lingering at Madeira-Mamoré stations en route, now mostly ghost towns.

Vila Murtinho, for example, a dozen or so houses around a barely recognizable square. Column in middle of soccer field commemorates 1822/1922 (Independence,) abandoned stores, inhabitants hanging around doing nothing in particular. Along the road, no evidence of real agricultural development in ten years since it was opened, usual burnt patches, some grassed areas, few cattle, all adding to depression one feels at sight of abandoned tracks, equipment, stations etc.

Some wide-ranging Eduardo pointers/ observations/ images on past and present as we traveled: a) all railroad equipment imported, including standards from London b) dormitory for visiting dignitaries above station at Guajará-Mirim c) struggling agricultural community with church under construction for five years f) small country hospital, male patients of all ages in general ward g) stream with beautiful bathing spot, Indian maloca upstream x 14 hours travel h) blue butterfly worth at least $50) balls of latex covering square in front of old station j) forest landing strips k) 25,000 hectare fazenda.

Weekend with Eduardo along Madeira-Mamoré railroad, in every retrospect, a valued experience. I have begun to see Vicente Cardoso's (Cavalcanti) experience in a very different light for two reasons: A) Rondônia provides bases of “last frontier” (soon to pass with coming of statehood.) B) Madeira-Mamoré story needs more than an outsider's view. Vicente has to be physically involved with the construction and thereafter gradually to become a “man of power” in the territory. All points to having Vicente actually engage on the construction of the railroad and emphasis of rubber boom.

Eduardo offered many leads to this in yarns like that of Maciel, the Brazil concessionaire who went batty after taking to Indian pagé's concoctions i.e. mushrooms of altered states variety. Rondônia is not “Amazonas” with all that name implies but all the ingredients are here, plus some of the unknown: a great river (Madeira); Indians of violent and pacific type: Caripunas and Novas Pacos; rubber boom; typical Trans-Amazonas type highway; pistoleiros and possesseiros; the old Wild west, to this day; great lumber enterprises; area south-west of Rondônia scene of gold rush today, dredging and panning rivers with some major finds of nuggets; significant immigration from the North-East, especially Ceará; Japanese farmers; migrants and adventurers from many lands, including descendants of the workers who came to build the Madeira-Mamoré; Shockness, Norman, the Asians, Lebanese. A microcosm of an earlier Brazil of the South and, in some respects, an unfortunate carry-over of problems of the North-East.

Spent hours talking as we traveled back from Guajará-Mirim yesterday banging along cratered road with stops at "Restaurante e Borracharia" for food and to fix tires i.e. "borracharia!"

Guajara-Mirim Road Brazil UysSome of Eduardo's points: The vast land extent of Brazil is totally deceptive for you have to fight the forest inch by inch, a battle that may never be “won,” possibly can never be won and, like so many confrontations leaves a trail of victims. In this case, some human but more the spoliation of nature as depicted in the charred hulks of forest giants fallen in grotesque ruin amid fields of ashes.

As the Indians showed centuries ago, so today: The soil thus “liberated” is able to produce a good first crop, the second is poor, the third a disaster necessitating a new clearing and leaving the forest to recover with a poor secondary growth

On North/South dichotomy: the people of the North-East, and by extension the north “migrants” are sufferers, they are martyrs who love the land no matter how cruel it may be to them and their children. The people of the South see them as the meanest laborers for whom there is little home, a burden for booming Brazil.

Edward offers an anecdote sadly familiar: “Waldemar” migrates from the North-East to São Paulo where he becomes a bricklayer engaged in the construction of one of São Paulo's skyscrapers. When it's finished, he is not allowed to enter!

On prospects of revolution: Ed refers, as do most people, to three safeguards: futebol, carnaval, loteria. (Looking at TV antenna atop the remotest shacks, I would add “TV” as fourth safeguard.)

He notes, too, that you don't launch a revolution on hungry bellies. Ché Guevara tried that in Bolivia and look what happened. The real incentive comes from a reasonably well-fed middle-class with more time to think and plan; the peasant has less time to do anything but “survive.”

A power-clique of generals and moneyed aristocracy call the shots at the national level. Men might change, as with appointment of Figueiredo offering apparent new image, but driving force and ideas remain the same. Backing the clique are multinationals and foreign banks, who in the foreseeable future make a drastic change of status quo impossible. Brazil has once again traded its independence for colonialism, this time no gunboats and foreign princelings but “economics.”

With leadership of Brazil, important to comprehend the “man on the second floor.” The real power is often held by people other than those in the “boardrooms;” people who stay out of the public eye and quietly exert Power.

Foreign influence in Brazil was same, for example, with “Ypiranga,” Strangford, Collingwood, backing independence not for sake of Brazilians but to gain a favorable trade and economic foothold for British interests. England's economic colonizer role was taken over by America and now a new “partner” is on the horizon: Japan, going after the vast mineral and natural resources

With an important difference, according to Ed: The Brits and Americans always looked down upon the Brazilians from highest level. Brazilians, because of the big Japanese community in their midst, have come to know and respect them as honest, hard-working; they trust the Japanese whereas long experience has led to wariness of the U.S. and the British.

Also effect, in a lesser way but no doubt important, of anti-U.S. propaganda over the years, with “Yankee Go Home” drummed into heads of South Americans. Conversely, though, average Brazilian has little love for Cuba which is seen as a “government mess.” Brazilians know what a sprawling bureaucratic muddle can result in through their own home-grown examples: They're not interested in importing something that could worsen the situation.

September 1 Flew from Porto Velho to Cuiabá, changed there and flew to Brasília and onto Rio de Janeiro. It's not merely the vast distance covered within one country but coming out of the bush, it strikes you dramatically: the difference between all the poverty and struggle you have seen in “greater Brazil” and the suited, suave, soft-leather shoe people here, all bound for Rio, which most people I've seen these past forty days will never set eyes on. The contrast is shocking. I have a picture of a quintessential Rio grand-dame, paunchy, loaded with jewels, transported to one of those “restaurantes e borracharias” alongside any sertão road I've traversed. The shock would undoubtedly bring on an attack of something or other just as would happen with a “madam” visiting So-we-to!

SHARE THIS PAGE!