São Paulo - September 22 - Ocotber 6

My first week in São Paulo was spent with my historian friend Antonietta de Aguiar Nunes from Salvador, who was attending a conference in the city. She showed me the historical São Paulo as I would never have been able to see myself - Bandeirante, Jesuit, “coronel,” sons and daughters of Empire, we followed the tracks of all in museums and at sites around the city, while continuing our exhaustive discussions and debates on the “Brazilian thing.”September 27 -- With John and Julie Tilley (names changed) at a fazenda in the rolling hills of Tietê. Weekend spent with this friendly American couple and friends, Ruth and Peter and Frida Ramirez from U.S. consulate in São Paulo. Does one good to spend time with reps of "dominant ideology" after so much local exposure. Some contradictions worth thought: Why, for example, is is possible for Tilleys to turn 250 hectares into a profitable multipurpose farm supporting 200 head of cattle? Why is it possible for multinationals to make success of farming in many arid areas, whereas whenever Brazilian government gets involved in operation it is run down by bureaucracy? Apparent failure over centuries if compared with rapid success of immigrant Italians, Syrians etc?

Was staggered to learn of 300,000 hectare sugar estates in São Paulo area: same exploitative attitude toward land as ever, transferred from north to south. On multinationals in Brazil, worth looking at conflict between nationalist desire to be rid of them and real need for their research and example etc.

September 29 - Have had a day for reflection on last weekend: despite Tilleys' sincerity and obvious good works on the fazenda, I cannot get away from the feeling of spending time with “colonials.” They've been here for twenty years, have obviously worked very hard at their 250-hectare holding, and have brought up their children in Brazil. Yet they talk with and show the same prejudices of most Americans, particularly when guard is dropped at cocktail hour. The distance becomes apparent on a visit to town on first night of festival of St. Benedict - I found it curious that as we walked through town, there wasn't a single local whom John or Julie greeted or stopped to speak with. It was incomprehensible, really, in the town where they lived for several years, not one person greeted them and vice versa.

Driving back with Ruth and Peter, journey was occupied with discussion of the “good America” image and reflections on why Brazilians have screwed up things and continue to do so; on “pinkies,” as Ruth calls them. On and on until we're nearly home and Ruth finally admits, Glory be, that she can see millions of people are deprived and things must be done to help them. She says she is worried about their “breaking things.” (quebra-quebra.)

You cannot ignore what John has achieved on his farm but neither can you ignore fact that he has a) knowledge and b) access to it. As I said earlier, it was a depressing weekend and certainly my last serious contact with estrangeiros living here. Back to the Brazilians!

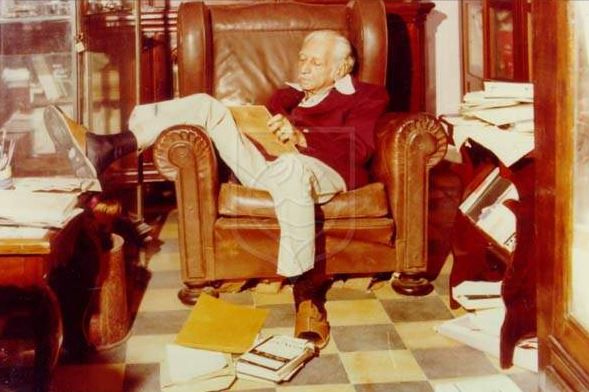

Am beginning to get restless. I feel quality of “discovery” is waning and that I must get down to specific research and writing. I have a broad grasp of Brazil, far more detailed and perceptive than when I started out, but I must begin to apply this. The gaps that remain are enormous but can be filled at home. Approaching the 90th day of this voyaging, I feel I am reaching the limits of absorption and must soon begin to release all that's been crammed into my head. Say half a dozen interviews and I will be ready - plus redoing my outline in light of all these “discoveries.”

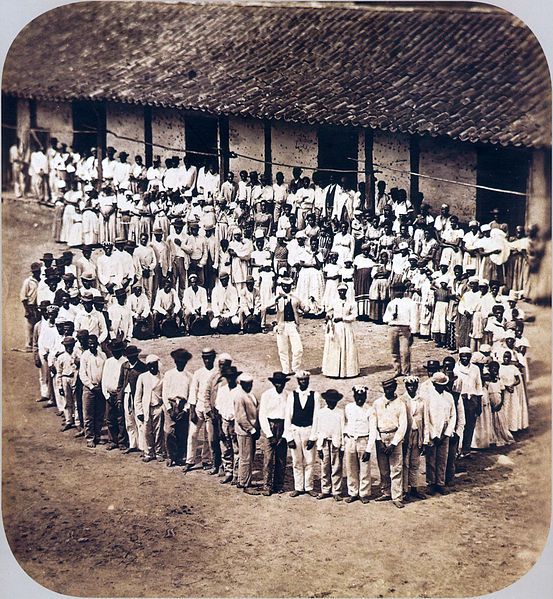

September 29 -- With historian, Fernão Novaes, who is working on book on slavery in colonial times, with special reference to period when Portuguese and others became conscious of evils of slavery and raised questions about it. (vide Viera, Manoel Ribeira da Rocha.)

Novaes theorizes that it is the slave trade, the economics of it that explains slavery, and not the other way around. Agrees that important questions remain unasked about Brazilian slavery. Why, for example, was there no breeding of slaves? Notes that most studies of slavery relate to 19th century and findings of that period are transposed to previous centuries. Circumstances might not be the same.

The U.S. form of slavery was totally “independent” in sense that it existed in the U.S. south alone and was not tied into a wider mother country. In Brazil there was no breeding, no independent operation.

From the beginning, manumission was seen as a good thing, as a way toward saving the owner's soul. The idea of full Christianization of slaves, other than simple act of baptism and saving of slave's soul, came with the Methodists and not before. In Brazil/ Catholic sense, the Christianizing was usually superficial.

Fernão agonizes over question of Brazilian identity: “The Mexican seeks an identity divorced from the Spanish in his Aztec heritage. Similarly, the Peruvian will claim a line to his Inca forbears. Indo-American culture, even if an illusion, is important - Brazilian identity exists but is difficult to conceptualize in similar terms. It is peripheral, not European, not centralized and yet clearly different from Latin America.” - "Yet,” says Fernão, "in the U.S., I feel Latin American but in Europe, France or England, I feel Brazilian!”

On contemporary politics: After the 1969-74 repression, a new force emerged based on a) syndicates who mobilized very differently b) a totally new church different from the past. (Symbolism: priest saying mass with back to people; today he faces them as he faces the problems of his nation.) Moved toward independent opposition as they were turned off by Communists + disturbed by lack of a democratic base, always worried by aspects of totalitarianism and authoritarianism. (Aside: Lula visited Lech Walenska, who warned him to stay out of politics; Lula said that to progress he had to have political base.)

Between '69-'74, Church was only voice of opposition. “Never forget importance of church in Brazil. Political parties look to the next election, the church does not. It has until Judgment Day to carry out its work.” ( Excellent point!)

Fernão is in general agreement with ELU observations on 'colonization'/ INCRA's Amazon disaster/failure of private enterprise to create opportunities for underprivileged in the new regions/internal colonization of Brazil/re-establishment of latifundia.

He seems more optimistic about positive elements that emerged in the military since 1974 and have led to “abertura”/ agrees on the pressure-cooker theory/ and, above all, agrees on the naivety of U.S. policy toward Brazil (as in South Africa) which may offer short-term benefits but in long term can alienate majority of Brazilians and create an irreparable break between the two giants of America.

October 3 - Missing entries but not quality of impressions! Today met for four hours with Luis Hafers, one of the great financiers of Brazil, just back from Washington where he negotiated a $60 million factory loan. He is a cousin of Eduardo Suplicy (interviewed previous day) A director of Matarazzo empire, owns coffee estate near Santos (calls himself a Santanista ), two farms in Amapa (2000 cattle) and Acre, fishing interest in Salvador, cotton trading business. Lived in very close family atmosphere - they go back 400 years — until he visited Alaska (!), first outside experience, “then went on to discover Brazil!” A handsome, slender man who plays polo, travels widely, well read.

Luis relates stories of his experience in the North-East and appears genuinely aware of the problems. He remembers times of drought and droves of people streaming into town in Piauí,, where family owned ranch. “They were quiet, very quiet because of their hunger.” Tells anecdote of sharing bowl of manioc with poverty-stricken blind violinist.

He has strong words against people who talk of “lazy North-Easterners” - If one of his Caterpillars has no fuel, no energy, it won't operate, he says by way of illustration. So, too, if one of his workers has no energy, insufficient food, he will be unable to work.

To Luis, key to Brazil's future lies in education. “Property will not yield power in Brazil anymore - education will. Even though education is backward, it is still a bigger force.”

Says São Paulo is a meritocracy, talks of power of Minas Gerais political bosses. Regards his cousin Eduardo as honest man pursuing hopeless ideals for PT; Lula etc. No effective platform and talk only in vague terms.

Brazil's progress bedeviled by bureaucrats who are conceited and intellectually dishonest. Says Brazil needs a Teddy Roosevelt who'll say “Let's do it” and the nation will get on with the task.

Agrees land situation is a mess and says Brazil needs a Land Act. “There is enough good land for all, distribution is delayed by bureaucracy and its endless studies/ tests etc.” But cerrado is not for the small farmer, a highly technical, complex land area.

Talks vehemently and with passion against priests, who he calls S-O-B's. He sees political priests as morally dishonest, “the poor man's Richelieu.” Does not believe that they're honest in their motives but merely seek to build the power of the church.

His anger against priests surfaced several times and he foresees a confrontation between them and the state. It happened in Dom Pedro II's time, he says, and he disposed of the question effectively and so it will be again. A confirmed churchgoer he regards religion as a very personal matter.

Speaks freely about his black ancestry, says Brazil essentially of Portuguese and African heritage with little other influence. Sensitive about question of lack of opportunity for blacks, quickly denying there is racism...

On Brazilian “independence,” accepts importation of technology etc. as necessary but in other areas, agriculture and “culture” proper, Brazilians must work it out for themselves. Describes those who talk about socialism for Brazil as “ pamphliteros.”

I sense that deep down while accepting “cheap” money for Brazil from outside, he resents it and would prefer Brazil to go it alone.

October 8 - Another Rodoviária! At least I can begin to think of it as “almost the last.” Only one more bus trip remains from Salvador to Rio and home.

Wonder what these people around me think of this foreigner sitting here scribbling away? I catch glances I cannot read. Of interest or envy? Or simple wonderment that someone should voyage so far...

These bus stations are equal to thriving airports U.S.-style It's difficult to say whether Brazil's policy of abandoning rail in favor of road was wise or not. Agreed, the decision was taken before oil price bust, but fact is it gets people moving at remarkably low cost.

Nearly two hours before departure of bus, find myself with 260cr. to get me to Bahia and Antonietta's doorstep. So while I wait let me take the time to wrestle with some of the “problems” that crept in recently, perhaps not so much problems as starting blocks.

Would it be valuable to show a) how society came together in the model cast for it by Gilbert Freyre, the formation of “Luso-Tropical” man. And while accepting this fusion as a fact to go on to propose and examine b) how and why it was split into the upper class who control the oligarchy and the power and the rest? So that with the South African experience in mind, you find that a visit to a favela can be described in precise the same terms you would use for a sojourn in Soweto.

Be careful, I caution myself, not to overdo the division. At the same time, you cannot ignore it, especially in coming to terms with the realities of Brazilian society found as you worked your way from bottom to top. (Contrast with all the past travelers here, their remembrances of days and nights in the Casa Grandes of Brazil!)

Could it be possible that while pursuing an intellectually honest path in his sociological research in the 1930s, Gilberto Freyre created a myth? That his simple interpretation of masters and slaves, casa grande e senzala, actually hid many of the realities of Brazilian society? That in accepting the uncluttered concept of paternalism on the plantation (and patriarchalism within the casa grande,) we ignore the situation of the population living beyond the plantation, the majority represented by the marginalized society of today? That there we find a divergent class structure as rigidly separated (by custom not law) as in South Africa? That transition from one level to another is as difficult as in the past and becoming more difficult? This needs more thought.

One thing that has long bothered me about the Cardoso/ da Silva line-up (my fictional families, later "Cavalcantis" and da Silvas) is that after the initial and obvious divergences they tend to become “look-alikes.” Their lifestyle and situation in Brazil is so similar as to make them representative of that small, traditional upper crust.

Since, as explained to Antonietta, I'm troubled by the absence of a black family and need to demonstrate the division of Brazilian society, it becomes apparent that the da Silvas (or whatever they're called) should fill this important role in a natural way (not contrived as, for example, with a fall from grace.) If they are going to represent the "other" Brazil, they must do so in the ordinary way that leads so many of Brazil's sons and daughters to being second/third-class citizens in the land of their birth. (In the manuscript, the da Silvas remained the quintessential Bandeirante/Paulista family. António Paciéncia, Patient Anthony, and his heirs represent the black family I envisaged here. (See the excerpt "Patient Anthony: The Story of a Brazilian Slave" which in introduces António's story.)

OK, let's wrestle with “keys” to the shackles...

(1) Man and the Land: Nowhere on so gigantic a scale has man confronted the challenge of the land or been faced by it. In the U.S. equally large, man was early on able to come to terms with the land, to advance little by little and adjust to it. (Remember, many of those newcomers to vast North America also originated from countries as small as Portugal.) In Brazil, for reasons not all clear, the fear of the land, the inaccessibility of it, restricted man's advance. When it happened it was, as so recently shown again, chaotic.

What if in the American mind, Canada's frozen north was a major part of the U.S.? What effect would that unconquerable domain have had on the national psyche, as the Amazon has had on the mind of the Brazilian? How do the countries of North Africa look upon the Sahara? How important was early Portuguese colonial attitude toward Brazil? How influenced were they by the humanist and romantic interpretation of Brazil - the “Paradise Found” school? Has the land's vastness diluted the spirit of European man in the tropics? What are the essential qualities,/drives of man the predator in relation to the forest?

I pose these ingredients to my theme of “land” in question form and while few could be answered simply all are tied together.

(2) Identity: The Brazilians' search for an identity of their own, cultural, national, personal - The answer to the question, “What is an Englishman?” “An Italian?” "A Portuguese?” is relatively unproblematic - but try posing that question in relation to a Brazilian and you'll have difficulty formulating a reply. He has been around longer than the Americans, the Afrikaners, the Australians and yet cannot be readily identified. Why? An intriguing question offering an important theme the book should answer.

(3) Independence: Alongside the quest for identity is the issue of independence. U.S. “won” its independence from the mother country. Fact is, Brazil never won its independence through foment or struggle but was handed it, as so many other things, so the oft-prided statement of being an “evolutionary” country raises some difficult questions. To this day, though its sovereign “border” is guaranteed, is it truly independent or does it go on inviting one or another type of “colonization?” From this you can argue in several valuable directions: Do the Brazilians see themselves as something in the nature of the world's stepchildren, always waiting for someone above to straighten things out?

Within each of these major themes/questions are many minor ones and from each there leads a sad consequence. - The land: latifundia, monoculture, greed, selfishness; The identity: almost discovered, almost unified and torn asunder by greed, by rapacity and the formation of class society; The independence: nearly “won” via Inconfidência, then “lost” via the handout of Empire, further “sold” to colonializing interests such as U.K. and finally, the multinationals. All back to square one, weep for the beloved Brazil.

Salvador and Rio de Janeiro,

October 14 — October 24

October 15 My latest Brazilian experience: At 1.23 a.m. this morning returning from a Candomble feast I was held up at gunpoint and robbed of watch and glasses (!) Two hours later in a gun battle between police and robbers, one was shot and arrested, two others got away.

After 100 days in Brazil and 20,000 relatively carefree kilometers, greet this incident with mixed emotions. Very real, very unreal.

After attending Candomblé ceremony at Casa Branca that ended around 12.30 a.m., Antonietta and I walked to bus stop. Caught bus at one and dropped at Sapateiros around 1.15 a.m. Broke one of my cardinal rules in avoiding trouble in truly decadent area: Gut feeling told me to take $1 taxi ride to Antonietta's house but she said no, it was safe.During day we'd argued over three “human nature” (evil) aspects of my plot. Walking along now, talking about people's “benevolent” nature, I challenge what I see as somewhat blinkered view of essential good in people.

Up ahead I see yellow car come to stop at side of road. Instinctively know that something's not right. See back door opening and man climbing out,and then a second man.

As man steps toward me I see large black gun in his hand. Tell Antonietta who has similar pistoleiro advancing on her not to resist. Mine asks for money. I've none but he sees my watch. Gestures with gun for me to take it off. Do so, swiftly. He frisks me. I've tight jeans on and nothing in my pockets. I'd run out of exchange dollars (Thank God.) Antonietta's bag taken, including six copies of Daily Post with feature story on ELU. She starts asking pistoleiros to return papers, keys, documents.

Not sure of what happened next but see police car approach on opposite side of street. Robbers still talking with Antonietta. I run over to police. Indicate that we've been robbed. Clearly, I am an estrangeiro in trouble in a bad district. What do police do. Drive off!!!

After police and robbers have gone off in opposite directions, we start walking toward Antonietta's mother's house. Panicky moment as car races up behind us, so decide to look for taxi. Equally unnerving since bus driver had earlier warned about “robber-taxis” operating late at night. Find reasonably honest-looking driver and go to mother's house for duplicate keys and taxi money.

No idea of sleep since we realize robbers had address and house keys. Antonietta phones police headquarters to report robbery and told to come into office in the morning. Sit talking about “human nature” (definitely evil,) when phone rings and we are summoned to district police HQ.

At 3 a.m. police confronted the robbers in a second stolen car. Gunfire exchanged. One robber shot across chest, arm and in leg. One policeman shot in shoulder. Second policeman hit in leg. Two robbers got away.

At police station, we are asked to participate in procedure known as “inflagrante” (same as delicto, I suppose!) According to Antonietta, it means that if a criminal is positively identified by victim within 24 hours, the same as if caught in the act.

I remember clearly the swaggering 5' 6” gun-toting thug who stepped over to me on Sapateiros. I recognize him as he's shoved into the office with battered face and obvious signs of a beating. He immediately confesses that we were two of people robbed (there were several other incidents that night by same mob.) Asks Antonietta to tell police that they didn't harm us, which she does. Asks me for a cigarette, which I refuse. He is taken away.

At this time, another criminal is brought in to office. One detective has a two-inch thick stick with which he proceeds to lambaste him in front of us.

Told to return at 9 for official charge. Takes two hours and includes signing document attesting to “identity parade.” No such parade took place but since positive ID of my attacker and he “agreed” it was us, not going to make issue. Police tell us that the three robbers included “Penguim,” (my attacker) and “Negronino do Religioso.” They stole yellow Brasília first, then swapped for blue vehicle. Attacked another couple after us and took the girl hostage; did not assault her and later dropped her some distance away.

Only slowly does it seep through one's mind that the robbers' guns were loaded and they were ready to use them. In retrospect I'm infinitely grateful that the police car that arrived on the scene had two dumb cops, for no doubt a gunfight would've ensued with us in the middle.

I suppose that 100th day in Brazil without such an “event” too good to expect.

Last week in Salvador is proving the most exhausting of all, as I wrestle with the problems of plotting. I feel quiet joy over the knowledge that home is but ten days away, suddenly truly tired of all this roaming.

This penultimate week in Brazil has indeed been a peculiar one, not alone for facing part of it at the point of a .38, but for the exhausting debate with Antonietta, a true Brazilian nationalist and idealist.

I find that instead of sympathizing with her stand on “Brazilianization” which I support, I'm turned off by notion of placing just about everything that's wrong with Brazil on the back of North America.

I was prepared to accept this up to a realistic and objective point but there came a moment where I found it plain ridiculous: the forest, the poverty, the revolution, the failure of Brazilian industrialists to develop their potential, the fracturing of Brazilian culture, the importation of alien foods, everything is the fault of “dominant North American ideology.” Certainly a great amount of blame in several areas can be attributed to this but to see the people of Brazil as some future “China” or “Albania” (sic) of South America is to deny the desires and hopes of what may be the majority, and to deny the enormous industrial and technological progress that has been achieved.

The kind of world envisaged may well lie in the future but for the present we are stuck with the “ugly” existence we have, with its emphasis on the individual and not some collective Utopian ideal. There is much I agree with, but I am disturbed by a lack of objectivity, the pamphleteering, as Luis Hafers called it.

Antonietta's sympathy for the “poor,” as she calls the man who held me up, is Christian, forgiving and noble but I cannot escape knowledge that the gun that was pointed at my guts, two hours later was used to shoot two policemen. The latter also seen as wicked, non-civic-minded types who delight in persecuting the Penguims of this world. Antonietta has a fine intellectual mind but sadly, a one-sided view: Be a Brazilian nationalist first but don't base that nationalism solely on “hatred for a common enemy.”

October 22 -- A beginning and an end! Here I am seated at Rio International Airport, 10.15 p.m. for flight home at 11.15 p.m. There is an element of unreality, just as at the beginning, way back there on Sintra Station in Portugal. A hectic last night dinner in luxury Rio apartment overlooking Copacabana Beach. Could not have been a better finale for it gave me a final glimpse of life “a la Rio.” Incredible statements from people such as, “Where is the sertão?” from my hostess, who lives a world away from the reality of Brazil.

I mentioned a “beginning and an end” - this is the latter but also a beginning for I now embark on the most exciting part of the book: The writing! There is a sense of having achieved what I came here for, of having “Brasil” within me. Tinged with a little fear for the task ahead. No, not fear but an awesome appreciation of the Reality. With “success” comes an exhilaration at having achieved this enormous voyage: No matter how long the road ahead, it can and will be traveled, as surely as I traveled thousands of estradas, asphalt or otherwise; as surely as I found my way into the minds and friendships of so many Brazilians.

SHARE THIS PAGE!