Excerpted from Brazil, a novel by Errol Lincoln Uys

"Uys re-creates history almost entirely at ground level, through the eyes and actions

of an awesome cast of characters." -- Publishers Weekly

August 1855 - January 1856

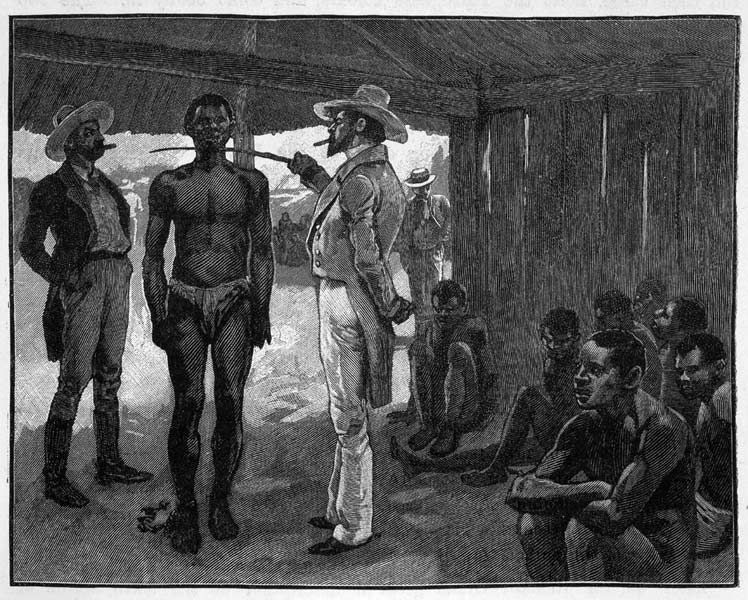

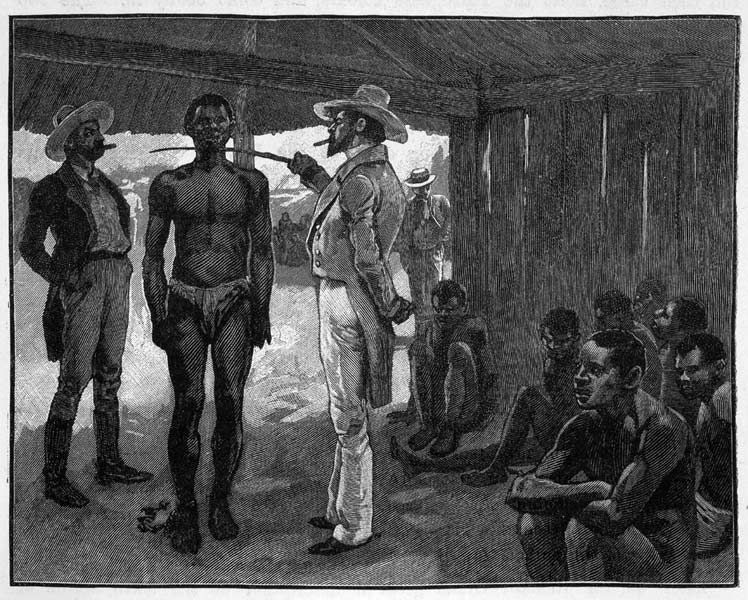

Antônio Paciência, "Patient Anthony," was eight years old on a day in August 1855 when he learned a terrible lesson. Until then, the dark-skinned mulatto boy had known no shame at being naked and often raced bare-bottomed to the Riacho Jurema to swim in the creek.

That August morning, a stranger came to Antônio Paciência, who stood naked with four others, and examined him with the thoroughness the boy had seen with vaqueiros inspecting cattle. His head, shoulders, arms, hands, trunk, legs, and feet were inspected. He was made to open his mouth wide to permit an examination of his teeth. The boy's private parts were searched. When his genitals were touched, Antônio Paciência uttered an involuntary cry, which made the stranger laugh and give the boy's testicles a vicious squeeze.

"As he grows older, senhor, he'll be a good worker."

Antônio Paciência stood with two older boys, a young man, and a girl. They were on the dusty open ground thirty feet away from the main house of Fazenda da Jurema.

After a while, Antônio Paciência raised his head slightly. He saw the senhor capitão sitting on the veranda, fanning himself with his hat. The senhor capitão's son was here, walking with the stranger as he inspected those selected to stand before him. Antônio Paciência's gaze shifted nervously from the senhor capitão to some women gathered off to the left between the house and a storeroom. He looked at the black slave Mãe Mônica - Mother Mônica," the senhor capitão fondly called her - who stood at the front of the group.

"Oh, Senhor Capitão, Antônio Paciência is a good child!" Mãe Mônica pleaded when she saw that her son had been chosen for the stranger. "Antônio will grow to be a man who faithfully serves the senhor capitão. As God sees me, I raise him with nothing but respect for the senhor and his family. Oh, my Master, for the love of Little Jesus of the Children, please, I beg for my Antônio!"

But the senhor capitão and the sinhazinha and the senhor capitão's son all ignored her.

Antônio Paciência's gaze moved to a group of vaqueiros in the shade of some trees beyond the storeroom. Several of his playmates were there, including his good friend Chico Tico-Tico, a scrawny, bow-legged caboclo. Tico-Tico, "The Sparrow," was twelve, a devil who led the gang of boys at the fazenda.

Senhor João Montes Ferreira, the senhor capitão's son, who stood with the Portuguese, remembered a night some eight years ago when he had raped Mãe Mônica, there on the hot earth beside the clay ovens at the fazenda. Senhor João Montes knew that the mulatto boy Antônio being inspected by the slaver was his son.

Senhor Capitão Heitor Baptista Ferreira was also aware of the bastard's parentage, but was not moved to compassion for Antônio Paciência. José Montes had five sons: three with his wife, Adelia Veras, and two acknowledged bastards with a vaqueiro's daughter.

João Montes had not shown the slightest affection for Mãe Mônica's child and the senhor capitão saw no reason to keep Antônio, especially with the Portuguese offering to pay grandly for healthy purchases.

João Montes had suggested that Mãe Mônica also be sold, a proposal strongly endorsed by his wife. She disliked Mãe Mônica, whom she knew to have given herself to her husband.

But his father would not hear of it. "The bastard can go, since you have no interest in him, but not Mãe Mônica." He had reminded his son of the slave's unmatched skills in the kitchen. "She stays!" Senhor Heitor had said, with a hand pressed to his barrel-like belly.

Heitor Baptista Ferreira's attitude toward the human livestock he was putting up for sale was typical of this poderoso do sertão, a great man of the earth whose grandfather, Militão Cariri Ferreira, a Paulista, had bought the fazenda from the Cavalcantis of Santo Tomás in 1781. Graciliano Cavalcanti had returned to Fazenda da Jurema after slaying Black Peter and avenging Paulo Cavalcanti's murder. But two years later, when his father, Bartolomeu Rodrigues Cavalcanti, died, Graciliano had gone back to oversee the engenho until Paulo's son, Carlos Maria, reached his majority.

When Graciliano left Fazenda da Jurema in 1768, he had deserted Januária Adorno Ribeiro, whom he had never married, and the children he had had with her. After reestablishing himself at Santo Tomás, Graciliano had married the daughter of a judge, fathering three girls with her. He had returned only once to the fazenda in 1779, to witness the effects of a two-year drought during which the forced slaughter or death by starvation of cattle had reduced the herd from eight thousand to less than one thousand animals. At the time, depressed sugar prices had made it impossible for the Cavalcantis to restock the ranch. When Militão Cariri Ferreira, who owned land north of the Riacho Jurema, had offered to buy the fazenda, Graciliano, who had inherited the ranch, had sold him the 180-square-mile property.

Senhor Heitor Baptista Ferreira was the acknowledged chieftain of a vast clan whose lands, encompassing the original Fazenda da Jurema and seven other ranches, amounted to a total of three hundred square miles. The Ferreira clan embraced not only relatives but also vaqueiros, rent-paying tenants, and agregados. The agregados, or associates, were permitted to live on Ferreira lands through ties of friendship with Senhor Heitor and other Ferreira elders, service as gunmen in conflicts with Ferreira enemies, and long, uninterrupted squatting during which they had always behaved themselves. Whites, mulattoes, caboclos, freed blacks - the agregados were the majority of occupants of Ferreira lands and were subject to immediate eviction if they offended the fazendeiro.

Fazenda da Jurema had been subdivided since Militão Ferreira's day, and the portion owned by Senhor Heitor covered eighty square miles, including the original settlement at the jurema trees near the confluence of the Riacho Jurema and the Rio Pajéu, an influent of the Rio São Francisco sixty-five miles to the south. Senhor Heitor's house was a big, bare, ugly structure with walls of unplastered rubble and a tiled roof. Nearby stood the slave huts and the vaqueiros' houses, one-storied, one-windowed hovels of wickerwork plastered with mud. A five-foot-high fence of upright stakes thickly interwoven with thin tree limbs and brush marked the perimeter of the settlement. The most striking aspect of the fazenda was how little it had changed since the time Paulo Cavalcanti and Padre Eugênio Viana had visited the ranch in 1756.

On the Ferreira lands, there were several families of Cavalcantes. The slight alteration in the last letter of the name - the "i" to an "e" - had first appeared in the documents of a criminal case involving Quintino Adorno Cavalcante, one of three bastard sons of Graciliano. The change assumed significance in differentiating between these improvident sertanejos, men of the sertão, and the senhores de engenho who, in this year 1855, still held fast to the lovely valley of Santo Tomás 220 miles to the east.

The boy Chico Tico-Tico - Francisco Cavalcante - and his father, Modesto Cavalcante, a vaqueiro at Fazenda da Jurema, were direct descendants of Quintino Adorno Cavalcante. Through three generations since Quintino's time, not one family of the Ribeiro-Cavalcante line had obtained possession of a single acre of land. Some Cavalcantes had served as vaqueiros with the Ferreiras and other fazendeiros; some had rented small sites in the district, where they grew subsistence crops; some had become nomadic, wandering far into the sertão in neighboring Ceará and south, too, down the valley of the Rio São Francisco. One family, who had fled the backlands after the 1845 drought, were living in a shack on the outskirts of Recife, with the father and two sons working as harvesters of blue crabs in mud flats near the city.

Among the seventeen families that could be traced to Graciliano and Januária in the year 1855, the highest position achieved by any member was that of an army corporal serving in the far west on the Rio Madeira. The most prosperous Cavalcante was the pilot of a barca on the São Francisco. The most educated was a young man of Chico Tico-Tico's generation who'd had three years at primary school.

If one of Graciliano Cavalcanti's descendants had prospered, as vaqueiros occasionally did, by building up his own herd with his annual share of new calves, he would have had difficulty finding land to purchase. For decades already, most of the 600,000 square miles of the semi-arid northeast sertão had been in the hands of families like the Ferreiras or held by absentee landlords at the coast. With a passion rivaling that that had possessed the lord donatários of Brazil three centuries ago, these poderosos do sertão believed in the splendor and the glory of owning immense territories. Nothing could be more injurious to their estate than to permit the sale of small patches of land where men of the lower classes might plant homesteads. Nothing could be more threatening to their control than to offer tenants contracts to remain permanently on their property.

Chico Tico-Tico's father, Modesto Cavalcante, was the only descendant of Graciliano still working as a vaqueiro at Fazenda da Jurema. Modesto had a wife and seven children, a mud-walled house, a dozen cattle, seven pigs, and a tame parrot. He had made many trips taking cattle to Recife, but his world lay essentially within the boundaries of the Ferreira lands, where he served the patrão with blind loyalty.

This day, when the Portuguese inspected Antônio Paciência and the others, Modesto Cavalcante was with the vaqueiros watching the slaver.

From Antônio Paciência's first night away from Fazenda da Jurema as he lay wrapped in his sister's blanket, weeping, until journey's end three months later, the boy was rarely spared sorrow and fright. Sometimes there would be a dull unreality without fear and he would play with other slave boys when the column rested at night, but it took no more than a sharp word from Tropeiro or another driver to start him crying for Mãe Mônica and the world he had left behind at Jurema.

Many sights on the long march awed Antônio Paciência, none more than the Rio São Francisco, which he first glimpsed from the Pernambucan bank opposite Joazeiro, where the river was 2,500 feet wide with banks rising twenty-five feet above low water. When he saw that they were to cross by ferry, he had shaken with fright, but once on the water, he had enjoyed the crossing. Saturnino Rabelo left the column several times to take a barca or a canoe upstream, but the slaves made the entire journey on foot.Seven slaves died from sickness during the march. And twice Antônio Paciência had watched as holes were scratched in the sand beside the road to bury infants born to slave mothers as the column rested at night. But the column was not reduced by these deaths: Saturnino Rabelo acquired seventeen additional purchases from fazendas along their route.

Even today, sixty-three years after the event, there were some older citizens of Rio de Janeiro who vaguely remembered Joaquim José da Silva Xavier as that "madman who had come down from the mountains of Minas Gerais with the crazed notion of making himself king of Brazil." This idea was all the more laughable today, since here, along streets where the Tooth-Puller had taken his last walk to the scaffold and dismemberment; the people often raised their voices exultantly to greet the carriages of true royalty.

For their subjects, nothing was so uplifting as the sight of an emperor and his family, in whose veins flowed the noblest blood of Europe.

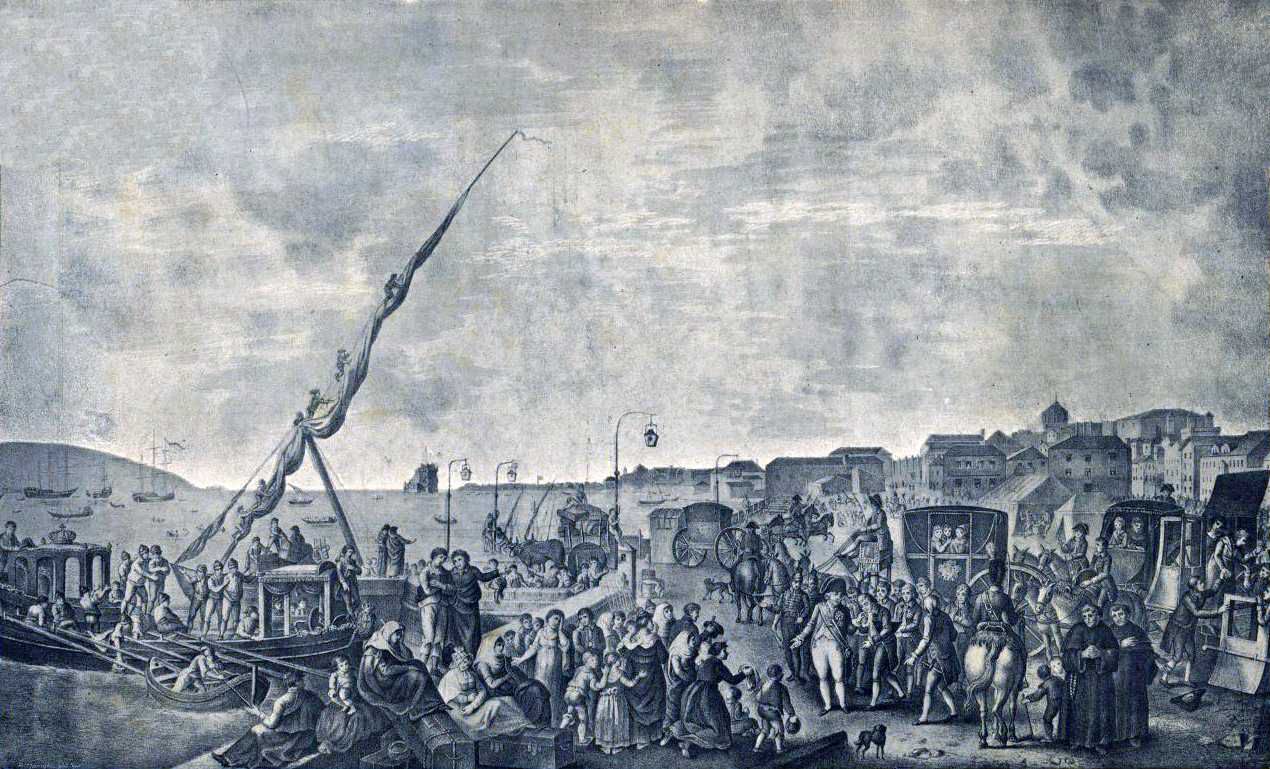

Insane Maria I of Portugal had remained queen, with her son, João, carrying out her royal duties as regent. Dom João would have preferred nothing more than the peace of the monastery at Mafra. Instead, he had to make some of the most painful decisions ever thrust upon a prince of Lisbon.

On August 12, 1807, France and her ally, Spain, had demanded that Portugal declare war on England, close her ports to English ships, and imprison English residents and confiscate their property.

Instead of waiting for the inevitable defeat of Portugal's small, ill-equipped army, Dom João and his ministers considered a daring plan: Why not move the court to America? From late September until mid-November 1807, Dom João and his ministers had engaged in a dangerous game of diplomacy. They offered to sign a secret treaty with the British to compensate them if they had to be denied access to the ports of Portugal. In return, England would provide an escort to Brazil for the Braganças if flight became imperative. This treaty had been signed in London on October 22, 1807.

Two days earlier, Dom João had informed the French that Portugal was closing her ports to the British. But Napoleon still demanded the detention of English residents. Dom João and his council had agreed to this, but several days before the proclamation, England's minister at Lisbon, Lord Strangford, was forewarned so that English residents could depart safely.

For a week, with a British squadron off the mouth of the Tagus, Dom João had waited for the French response to his decree against the English residents. Napoleon's answer came on November 23: General Andoche Junot and his army crossed the northern border of Portugal. And from Paris had come news of a pronouncement from Emperor Napoleon himself: "The House of Bragança has ceased to reign in Europe."

The Principe Real, carrying Queen Maria, Dom João, and his sons, had made its landfall at the Bay of All Saints on January 17, 1808. Within four days of Dom João's arrival, the prince regent had agreed to open Brazil's major ports to friendly nations and to permit free trade between his vassals and foreigners, thus demolishing the cornerstones of Lisbon's three-hundred-year-old policy of monopolizing and exploiting the wealth of Brazil.

The proclamations aimed at improving conditions in Brazil had not ceased. At Rio de Janeiro, where the House of Bragança had quickly taken root in its lush tropical domain, along with more than twelve thousand refugees, reforms that had been unthinkable at faraway Lisbon were magnanimously granted. Royal edicts abolished all restrictions on manufacturing and industry, and printing presses were permitted; schools of medicine and surgery and academies of higher education were established; a Bank of Brazil was founded; foreigners were welcome.

Within ten months of the Braganças' departure from Portugal, a British force defeated the French. Dom João could've returned, but the French had overrun Spain, and the prince regent thought it wiser to stay in Brazil while the Iberian Peninsula remained a battlefield.

On December 16, 1815, Dom João elevated Brazil from a colony to a kingdom coequal with Portugal. Three months later, Dona Maria died. Dom João became king — João VI of Portugal, João I of Brazil - and still he refused to return to Lisbon.

From his vantage point at Rio de Janeiro, Dom João had observed the beginnings of the disintegration of the Spanish viceroyalties, and deemed it inadvisable to return home until his kingdom of Brazil was safe from contamination by the revolutionary turmoil beyond its borders. Besides, there was a conquest on which His Majesty had set his heart since arriving in America: the Spanish province of the Banda Oriental, east of the Rio Uruguay and extending south to the Rio de la Plata.

Spanish America had witnessed the first rebellion against vice-regal authority in 1810: At Buenos Aires, capital of the extensive viceroyalty of La Plata, a junta had arrested and deported the viceroy. As the Buenos Aires republicans moved closer to a full declaration of independence, they struggled to unite the provinces of La Plata. An early loss to this cause was Paraguay, which had always resented the wealthy and politically powerful porteños, those who lived in the port city of Buenos Aires, one thousand miles down the Paraguay and Paraná rivers. Paraguay was declared an independent republic in 1812.

Like the Paraguayans, the sixty thousand inhabitants of the Banda Oriental, led by José Gervasio Artigas, did not want to submit to Buenos Aires and agitated for a loose federation of the La Plata provinces. When, on July 9, 1816, the independent Republic of Argentina - a Latinization of the Spanish "Plata" - was born, José Artigas persisted in his refusal to accept the central authority of the porteños. It had seemed that the Banda Oriental would follow the example of Paraguay, but then Artigas made a fatal error: Bands of his gaucho cavalry violated Brazilian soil, infiltrating into Rio Grande do Sul in 1817.

Dom João sent his forces against Artigas, contemplating a swift campaign to settle the ownership of the Banda Oriental. But bands of gaucho guerrillas continued to harass the Portuguese for three years. By 1820, however, they had been decimated, Artigas had taken refuge in Paraguay, and at last the way had been open for annexation of the Banda Oriental as the Cisplatine Province of Brazil.

Dom João had made his conquest, but his satisfaction had been ruined by events in Portugal. Revolutionaries had convoked the Cortes, the Portuguese parliament, for the first time since its suppression in 1689 and demanded the return of the Braganças and the king's adherence to a proposed constitution.

Among those gathered to bid farewell to the king had been a handsome young man: Crown Prince Pedro. In his son, Dom João had seen hope of preserving intact the Braganças' American estate. "You will maintain our family's presence as my re gent," Dom João instructed Pedro. "But should Brazil decide to separate herself from Portugal, let it be under your leadership, my son, not that of an adventurer, since you are bound to respect me."

At the time of the Braganças' flight to Brazil, Prince Pedro had been ten years old. Short and stocky, with a handsome face dominated by large brown eyes, Dom Pedro had thrived in his exotic place of exile. Generous and friendly, Pedro was also impulsive, emotional, and had shown a passion for lovemaking. Week after week, he would hasten from São Cristovão in search of new lovers from all classes and races.

When Pedro was eighteen, Dom João had dispatched a mission to Europe charged with finding a wife for his son. At Vienna, the matchmakers had gained for Pedro the hand of the Archduchess Maria Leopoldina, daughter of Francis I of Austria and great-granddaughter of Maria Theresa. In 1817 the plain, flaxen-haired Leopoldina had sailed for Brazil where she married Pedro, two years her junior.

Pedro had been awed by his wife's superior intellect, particularly her abiding interest in botany and mineralogy. But neither marriage to Leopoldina nor the birth of his first child, Princess Maria da Glória in 1819, had distracted Pedro from his paramours.

When King João sailed for Portugal, the twenty-two-year-old Pedro had been ill-prepared for his duties as prince regent of Brazil. But able advisers from among the Portuguese and mazombo aristocracy had surrounded him, and they guided him through a stormy eighteen months as his regency followed an increasingly divergent path from that sought for it by the Lisbon Cortes.

With King João back on Portuguese soil, the Cortes had insisted - on the pretext that the heir to Lisbon's throne should be given a sound European education - that Pedro and his family also return to Europe. But, at Rio de Janeiro, Prince Pedro had been presented with a petition signed by eight thousand citizens calling on him to resist the Cortes' demand. "For the good of all and the general happiness of the nation, I am ready," Pedro had announced. "I will stay!"

Nine months passed during which Brazil had drifted further from the grasp of the Cortes. Dom Pedro had formed a new ministry, which included a distinguished Paulista intellectual, José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva, the first Brazilian to hold the key post of minister of the kingdom. And the prince had convened a constituent assembly, with representatives from the provinces, as the former captaincies were known.

The final break with the Cortes - and Portugal - had come on September 7, 1822. Dom Pedro had traveled to São Paulo to unify resistance against the Cortes and was returning to that city after a brief visit to the port of Santos when court messengers from Rio de Janeiro overtook his party at a small stream called Ipiranga. They were carrying dispatches from Minister José Bonifácio, who submitted the Cortes' latest decrees revoking the Brazilian assembly as a rebel body and calling for the dismissal of Dom Pedro's ministers, whom they declared to be traitors.

There was a letter, too, from Dom Pedro's wife, Leopoldina: "Pedro, this is the most important moment of your life. Today, Brazil, which under your guidance will be a great country, wants you as her monarch." Leopoldina and José Bonifácio urged Pedro to declare himself either king or emperor of Brazil.

Dom Pedro had made his decision, beside the stream at Ipiranga: "I proclaim Brazil forever separated from Portugal! From this day hence, our motto is: Independence or Death!"

Emperor Pedro was crowned in the cathedral at Rio de Janeiro on December 1, 1822, commencing a nine-year reign that had been agitated from the start. Even as he sat on his coronation throne, the northern provinces of Bahia, Maranhão, and Grão Pará were still controlled by forces loyal to the Cortes. To expel the Portuguese garrisons, Dom Pedro had sought the assistance of an Englishman, Admiral Thomas Cochrane. With Cochrane commanding a "fleet" of two battle-ready ships and with Brazilian patriots attacking them on land, the last Portuguese garrisons had surrendered by August 1823.

Emperor Pedro had counseled the constituent assembly that the committee responsible for drafting a constitution must produce a document worthy of him and of Brazil. The assembly had considered it their right to present a constitution to which the Crown should adhere no matter what Dom Pedro thought of it. By the time a document was put before the assembly that September of 1823, the debate had grown so acrimonious that Dom Pedro dissolved the assembly and sent several members into exile, including the former minister José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva.

Emperor Pedro and his Council of State collaborated on a new constitution for the Brazilians, which provided for a moderating power for the emperor: Among his rights were the appointment of one third of the senators and the appointment and dismissal of ministers of state.

At Pernambuco, following the constitutional crisis, four northeastern provinces declared their independence as the Confederation of the Equator. Six months later, the last republican stronghold had fallen: Fifteen ringleaders had been executed by a firing squad.

Despite this success against the republicans of Pernambuco, Dom Pedro's image had been steadily deteriorating among loyal Brazilians who found his partiality toward the Portuguese infuriating. Dom Pedro also suffered an irremediable blow to his esteem when trouble again arose in the far south, in what was now known as the Cisplatine Province: In 1825 a group of thirty-three guerrillas encouraged by the Buenos Aires government crossed into the territory from Argentina to liberate it from the Brazilians. Within three years, following a war between Brazil and the Argentine confederation, the conquests east of the Rio Uruguay had been lost.

Throughout these years of controversy and conflict, Dom Pedro's private life, too, had left much to be desired, especially among mazombos who were distressed to see the emperor engaged in scandalous pursuit of new loves.

Pedro had taken as favorite concubine Domitila de Castro, a vivacious Paulista in her twenties, and had installed her in a mansion at Rio de Janeiro, where she had given birth to a succession of royal bastards. Domitila had been honored by her lover, first with the title of Viscountess, then with Marchioness of Santos; the firstborn love child had been acknowledged by Dom Pedro and ennobled as the Duchess of Goiás.

The erudite Empress Leopoldina had mostly suffered in silence, while bearing her unfaithful spouse's many children. Besides their firstborn, Maria da Glória, there were three other princesses and three princes, two of whom died in infancy, the third, Pedro de Alcantara, born on December 2, 1825 - Just over a year later, Dona Leopoldina herself died after a miscarriage.

A remorseful Dom Pedro set about reforming his ways. He sacrificed Domitila and sought a new bride. His emissaries succeeded in gaining for Pedro the hand of an enchanting Bavarian princess, Amélie of Leuchtenberg, granddaughter of Napoleon and Josephine Beauharnais.

Dom Pedro celebrated the arrival of his seventeen-year-old bride by creating the Order of the Rose in her honor: Love and Fidelity was its motto.

In the euphoric months after Princess Amélie's arrival, Pedro had been encouraged to set up a moderate cabinet comprised for the first time of Brazilians, but reactionary Portuguese intimates had induced him to dismiss this ministry. Street battles broke out in Rio de Janeiro - "The Night of the Beer Bottles" - between Portuguese absolutists and Brazilians. Members of the assembly petitioned the emperor to reverse his decision. Again he appointed a Brazilian cabinet, without success: Within seventeen days, those ministers had been thrown out of office and a pro-Portuguese cabinet once more installed. On April 6, 1831, thousands of protestors took to the streets; by midnight, the emperor faced a full-blown revolution, with the Rio de Janeiro garrison joining the street mobs.

Dom Pedro agreed to leave Brazil immediately for Europe, abdicating in favor of his son, Dom Pedro de Alcantara, who was then five years old.

In September 1855 Pedro Segundo was twenty-nine, with manners and appearance the very image of imperial dignity. His Majesty was over six feet tall. His countenance was frank and open, aided in this effect by direct blue eyes; his hair and full beard were a light golden brown.

Three years after the abdication, Pedro I died in Portugal. Thus, at the age of eight, Pedro Segundo had been orphaned, and to the regency that ruled Brazil during Pedro's minority, and his governesses and tutors, was given a unique opportunity to instill in him those attributes of justice, wisdom, and honor they deemed most desirable in a benevolent monarch.

As he grew older, the regents and ministers of state had broadened the boy emperor's knowledge of his domain, which, during the nine years of the regency, had often seemed to be on the point of disintegration, through regional violence and sedition.

The boy emperor had been instrumental in preventing the breakup of the empire, for he had been adopted with affection by the Brazilian people and served as a powerful symbol of national unity. In 1840, at a critical period of the regional conflicts and when the assembly itself was shaken by disunity, Pedro was only fourteen - four years short of his majority but, in response to the wishes of the assembly, he agreed that he was ready to oversee the affairs of his subjects. The assembly proclaimed him sovereign of Brazil, and the following year, he was crowned as emperor.

Dom Pedro, as his mentors had hoped, was adopting a benevolent and paternal attitude in his rule. For example, once a week he would receive members of his Brazilian family at court: exalted nobles, and humble Negroes, and representatives of the few remaining Tupi-Guarani clans.

Yet, for all the respect and esteem shown him, the emperor was prone to a melancholy reflected even in his dress. For official ceremonies, he would appear in full court regalia, but by choice he wore a black suit with frock coat, black cravat, and tall black silk hat, like a man in mourning. His childhood loneliness had not been relieved when a bride was brought for him from Europe: Empress Theresa, whom he married in 1843. Short, slightly lame, brown-eyed, and the essence of plainness, Dona Theresa had been twenty-one when she arrived at Rio de Janeiro.

There had been four children born between 1845 and 1848: Afonso, the firstborn, Pedro, Isabel, and Leopoldina. Within two years of their birth, both sons had died.

Dom Pedro's personal sorrows ran deep, but there was also another cause for his melancholy in the radiant tropical land he had been born to rule: He wore his crown reluctantly, yearning for the retreat of a contemplative and scholarly life and dreading the storms of statesmanship.

"Were I not emperor, I should like to be a teacher," Pedro said on occasion. "What calling is greater or nobler than directing young minds?"

Regularly, Pedro would visit schools and academies at the capital, personally inspecting their facilities and encouraging the pupils, for he was greatly distressed by the abysmal lack of education among his subjects, whose numbers had grown since his father's time to some eight million.

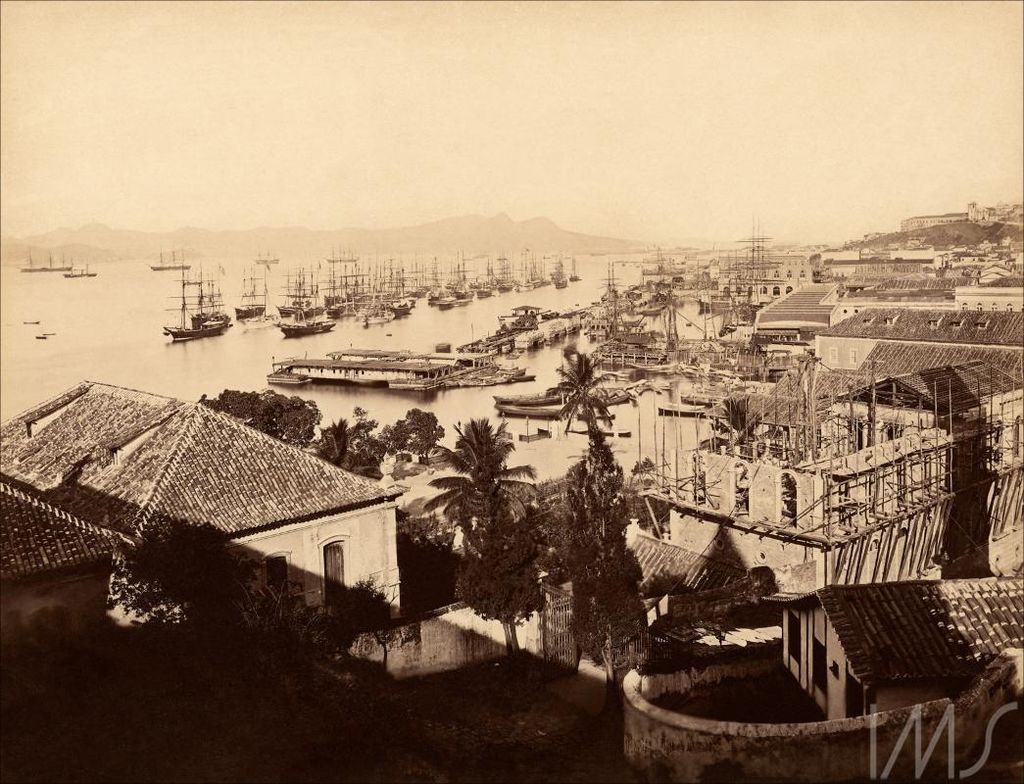

At the Corte, as the capital was known, Dom Pedro and his American aristocrats lived with a semblance of European elegance, scrupulously observing court etiquette, worshiping foreign ideas, and devotedly following the latest French fashions. Rio de Janeiro was slowly outgrowing its colonial jumble and squalor. Its bustling streets in the central district contained shops of French merchants and craftsmen who supplied the coveted finery; the counting houses of English traders; the establishments of the ubiquitous Portuguese shopkeepers; and, of course, the enormous bureaucracy of imperial government, to which thousands swarmed for emoluments.

The city's oil lamps were being replaced by gaslights; unhealthy marshes on the outskirts of the Corte were being filled and drained; and across the bay, from the small port of Mauá, A Baronesa! - the first locomotive in Brazil - shrieked and roared along ten miles of track to the foothills of the Serra da Estrela and the road to Petropolis thirty miles away, the summer retreat of the emperor and his family.

The city was spreading north toward the district of the emperor's palace and south into the shadows of Corcovado and Tijuca. At the small bay of Botafago, with the Sugar Loaf to one side, between thick groves of large-leafed banana trees and stately palms, stood the sparkling white mansions of viscounts, barons, generals. Tropical plants and trees flourished, dense and deeply green, and gaudy blossoms of scarlet, lilac, and blue mixed with the rose and other European imports. In the open valleys behind the city, there was often heard the baying of hounds and bugle blasts as sturdy, pink-cheeked Englishmen thundered after their quarry. In the city itself, at the waterfront public gardens, the scene was more placid, the afternoon sun often slanting down upon a sea of bobbing lace and parasols and gently wafted fans, and high silk hats of black and gray.

The court, the aristocrats and foreign merchants, the wealthy coffee growers - all these formed only a small upper class at the capital. Much more numerous were the free commoners and droves of wary-eyed provincials come from the sertão to behold the wonders of the Corte.

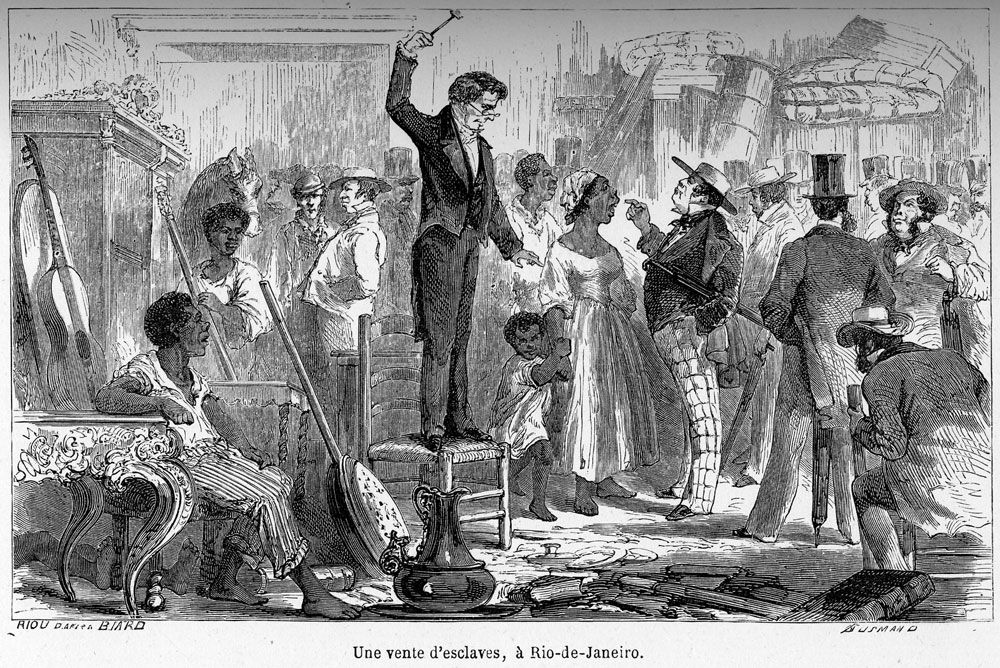

Half the city's population were black and mulatto slaves: The narrow streets teemed with half-naked men fulfilling the age-old promise that homens bons be spared the curse of manual toil in Brazil. The sun that shone on a sea of bobbing parasols at the Passeio Público elsewhere fell upon 130-pound bags of coffee borne by human transport chains whose leaders shook rattles to keep up an energetic pace; upon grand pianos lifted high and trotted through the streets by sweating Africans; upon water carriers thronging at the fountains to draw from what was still a hopelessly inadequate supply; and upon slaves for hire selling their master's fruit, fish, and poultry or bending over braziers with pots of spicy stew or waiting patiently outside their owner's establishment for those who would come to buy their labor.

Dom Pedro disliked slavery, as much from his moral upbringing as from the offense given by a horde in bondage at a capital that sought to be the Paris of America. The emperor had liberated the slaves he had inherited but dared not exceed this personal magnanimity: Talk of the emancipation of slaves stirred up the wrath of senhores de engenho and fazendeiros, whose plantations provided the empire's greatest wealth. Sugar, cotton, tobacco - all continued to yield good profits, but today's El Dorado was coffea arabica.

The coffee groves from those first seeds brought from French Guiana to Pará in 1726 and experimented with elsewhere in the north by growers like Padre Leandro at the aldeia of Nossa Senhora do Rosário had provided seedlings sent to the south before the turn of the century. Today, in the valleys behind Rio de Janeiro and spreading west to the province of São Paulo were tens of millions of coffee trees providing a bountiful export and firmly establishing in the south the same latifundia as existed in the north. And like the independent lavradores who had lost their cane fields to the big engenhos, southern smallholders in the path of coffee's advance were pushed out or absorbed as agregados by the fazendeiros.