Antônio Paciência, “Patient Anthony,” is eight on a day in August 1855, when the slaver Saturnino Rabelo buys him from Heitor Baptista Ferreira at Fazenda da Jurema. The Cavalcantis sold their ranch to the Ferreira family half a century ago. Senhor Heitor is a poderoso do sertão, “great man of the earth,” chieftain of a feudal-like clan whose lands encompass three hundred square miles. Ferreira is aware that his son, João Montes, raped the slave Mãe Mônica and is the boy’s father. He is unmoved by Mãe Mônica’s plea to keep her child.

Antônio Paciência joins a column of 167 slaves being marched from the north of Brazil sixteen hundred miles south to the coffee groves of São Paulo. Brazil’s internal traffic is a response to a ban on the slave trade from Africa, which saw 3,650,000 blacks carried to Brazil over three centuries, almost ten times the number that reached English America.

Policarpo, a Mozambican-born slave in his late twenties, befriends Antônio on the long journey up the Rio São Francisco valley. Antônio has heard others talk respectfully of “Dom Pedro Segundo,” but knows nothing about this poderoso said to have power over all Brazil. Policarpo has seen the grand patrão riding along the rua Direita at Rio de Janeiro in an open carriage with eight cream-colored horses: Dom Pedro II, emperor of Brazil.

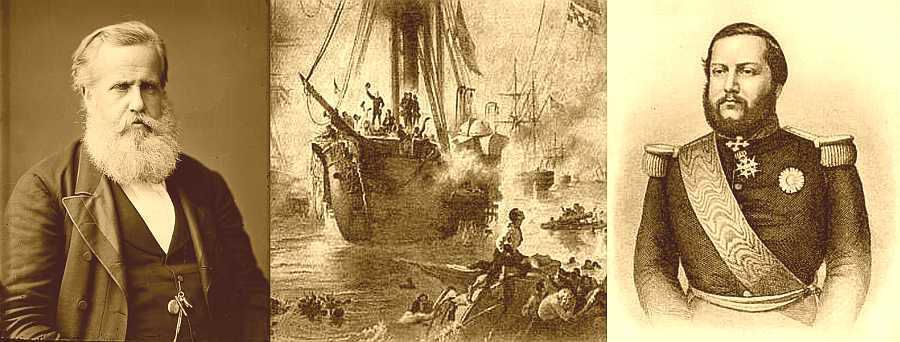

The Bragança royal family moved to Brazil five decades earlier, escorted from Portugal by a British squadron even as a Napoleonic army invaded the kingdom. The court of Queen Maria I was established at Rio de Janeiro, the colony elevated to a kingdom in the reign of her son, João. Dom João returned to Lisbon at the demand of the Cortes, the Portuguese parliament, leaving behind his 21-year-old son, Pedro, as his regent in Brazil.

When the Cortes insisted that Pedro also return to Europe, eight thousand citizens called on him to resist. On September 7, 1822, at the small stream of Ipiranga near São Paulo, Pedro proclaimed Brazil’s independence from Portugal. Two months later, Emperor Pedro was crowned in the cathedral at Rio de Janeiro, beginning an agitated nine-year reign that saw a republican uprising in Pernambuco, war with Argentina, and a succession of royal bastards fathered by His Majesty.

Pedro’s marriage to Archduchess Maria Leopoldina, daughter of Francis I of Austria, produced six children, including Pedro de Alcantara, who was five in 1825, when Pedro was forced to abdicate in his favor. Pedro I died in Portugal three years later and Pedro II ascended to the throne. The boy emperor was adopted with affection by the Brazilian people and served as a powerful symbol of national unity. A benevolent, erudite monarch, Pedro II is prone to melancholy in the radiant tropical land he was born to rule, yearning for the retreat of a scholarly life.”Were I not emperor, I would like to be a teacher,” he says.

On January 28, 1856, Antônio Paciência is with 175 slaves presented to prospective buyers at Saturnino Rabelo’s barracks at Sorocaba, sixty miles west of São Paulo. Rabelo is particularly attentive to one fazendeiro, who is seeking no fewer than thirty purchases:

Ulisses Tavares da Silva, the son of Silvestre and grandson of Benedito Bueno, is in his late sixties. Accompanying him is his grandson, Firmino Dantas da Silva, a pale slender youth. Ulisses Tavares was a student at Coimbra when Portugal was invaded and took up arms against the French; in September 1810, he was wounded at Bussaco, where 51,000 British and Portuguese defeated 65,000 Frenchmen. Five years later, back in Brazil, he’d gone to war again, for the conquest of the Banda Oriental, lands which were lost three years later extinguishing Brazil’s hope of extending its southern border to the Rio de la Plata.

In the mid-1830s, fazendeiros above the Rio Tieté had begun to grow coffee. By 1856, Ulisses Tavares is working 127 slaves and has more than 300,000 coffee bushes on a thousand acres at Itatinga. For his services to the empire, Dom Pedro II has made Ulisses Tavares da Silva a baron, his title derived from the lands he owns: Barão de Itatinga.

At Rabelo’s barracks, the baron selects twenty-five males and five females, Policarpo “Mossambe” among the adults he chooses. Antônio Paciência sits with the moleques, little black boys, and two other mulatto boys, feeling the misery of parting from Policarpo. But the children are hurried over to stand in front of Ulisses Tavares, who likes the look of the dark-skinned mulatto with his big eyes and honest face. To his relief, Antônio is bought by the baron.

Antônio is perplexed when they halt at Tiberica and the baron’s grandson marches him to the most prosperous store in town. Ulisses Tavares himself outfits the boy in a white blouse and long gray trousers hitched up with bright red braces. He is made to ride beside the driver of the baron’s carriage on the six miles to Itatinga, where the sprawling mansion occupied by Ulisses Tavares and his family stands amid tufted royal palms.

Antônio waits at the entrance to the house, while Firmino Dantas fetches a young girl, whom Antônio takes to be Firmino’s sister. She is Teodora Rita Mendes da Silva and in a week’s time, she will be thirteen, a tempestuous girl with small black eyes and a sharp tongue. Teodora Rita is the wife of 67-year-old Ulisses Tavares, a widower who doted on the child since meeting her at her father’s house two years ago. Emilio Mendes, a wealthy fazendeiro and dear friend of the baron, gave permission for their marriage.

Ulisses Tavares tells his child bride that Antônio Paciência is for her, a gift for Teodora Rita’s birthday.

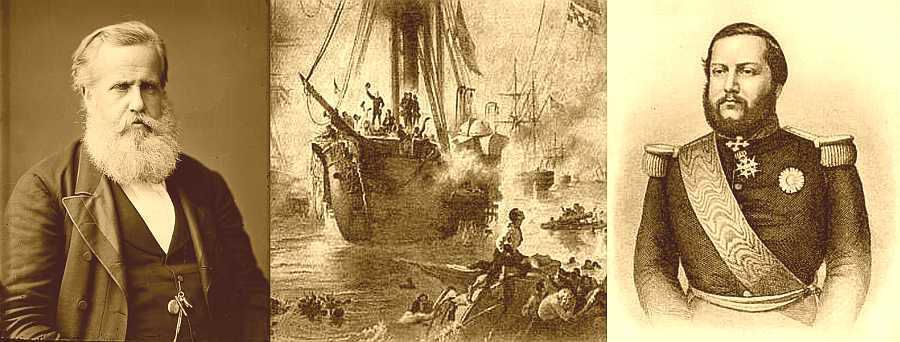

On November 12, 1864, Marqués de Olinda, a Brazilian vessel, is stopped and seized by a Paraguayan warship, the packet’s crew and passengers interned at Asunción. This is one of several actions that precipitate the War of the Triple Alliance that sees Brazil, Argentina and the Colorado faction of Uruguay taking the field against Paraguay. President Francisco Solano López leads an army of 40,000 soldiers, mostly Guarani and their mestizo descendants, with a corps of foreign engineers responsible for Paraguay’s defenses, including the fortress of Humaitá on the Rio Paraguay, “the Sevastopol of South America.”

Ulisses Tavares confidently predicts that Brazilian forces will occupy Asunción in three months and crush the ambitions of “Emperor López, Napoleon of the Plata,” and his Irish mistress, Eliza Alicia Lynch. Firmino Dantas da Silva will lead ninety-two voluntários da patria from Tiberica, including Antônio Paciência and Policarpo Mossambe, among six slaves “donated” to Dom Pedro II’s army by Ulisses Tavares. At a grand ball on the eve of leaving for the war in February 1865, Firmino Dantas is swept off his feet by Renata, the daughter of August Laubner, a Swiss apothecary settled at Tiberica.

At Riachuelo on a great bend of the Rio Paraná, a Brazilian squadron with nine ships engages a Paraguayan fleet in a bloody battle that rages seven hours. Second-Lieutenant Fábio Alves Cavalcanti is assistant surgeon on the corvette Jequitinhonha, which runs aground in range of Paraguayan shore batteries, almost half her crew killed or grievously wounded, before the Paraguayans break off action and withdraw above the Paraná.

The Tiberica voluntários serve with the First Corps under General Manuel Luís Osório, when the Allies invade Paraguayan soil in April 1866. “O Pensador,” (“The Thinker,”) as Firmino Dantas’s fellow officers call him, has no stomach for war, unlike his cousin Clóvis Lima da Silva, artillery major with the Batería Mallet. – Clóvis is descended from André Vaz da Silva, who died in exile in Africa. – The cousins take the field together at Tuyuti, where thirty-five thousand men with a hundred field guns are attacked by twenty-three thousand Paraguayan cavalry and infantry. Firmino Dantas is terror-struck when his position is overrun by Guarani cavalrymen. The guns of Batería Mallet hold, until Manuel Luís Osório himself leads an infantry charge that smashes the Paraguayan line. Policarpo Mossambe is singled out by Osório for a battlefield promotion to corporal.

Tuyuti is the first of many land battles in the bloodiest war fought between nations in the Americas. At Curupaiti, an advance battery six miles below Humaitá, Policarpo and Antônio storm an abatis; a shell explodes in front of the tangle of branches killing Policarpo and knocking Antônio senseless. Five thousand Brazilians and Argentinians lie dead; the Paraguayans count only fifty-four casualties. Two weeks after Curupaiti, Emperor Pedro II issues a decree freeing 25,000 slave soldiers serving in the Imperial army, too late for “Policarpo Brasileiro,” as Antônio salutes his friend.

Hadley Baines Tuttle, a young Londoner who fought at the Crimea, is an assistant to Colonel George Thompson, a former British army officer serving in Paraguay. They build forty-two miles of trenches and fortifications at Humaitá and eight riverside batteries that keep twenty Brazilian warships at bay for more than a year. The waters of the Rio Paraguay are made deadly with hundreds of floating torpedoes devised by Luke Kruger, an itinerant tinkerer from Pittsburgh in the United States, master-torpedoman for Marshal-President López.

In the third year of the war, the two armies are ground to a halt, a murderous summer seeing thousands of men carried off by cholera and typhoid. Three times López seeks peace, but is unwilling to accept a demand that he leave Paraguay. Dom Pedro’s minister of war, marqués de Caxias, takes command of the Brazilian forces and readies 30,000 men for the encirclement of Humaitá. In a second Paraguayan attack on Tuyuti, now main supply base for the Allies, Clóvis Lima da Silva is taken prisoner; Firmino Dantas is severely wounded at the very site where he cowered during the earlier battle.

At Paso la Patria hospital, Firmino is treated by Lt. Surgeon Fábio Alves Cavalcanti, from whom he learns that Renata Laubner is a nurse volunteer in Paraguay. He has a chance to see Renata when the ship carrying him back to Brazil stops at Corrientes, but he stays aboard, quite correct in sensing young Cavalcanti’s own love for a perfect angel from Tiberica.

Major Hadley Tuttle commands the Batería de Londres on February 19, 1868, when the Brazilian squadron runs the gauntlet at Humaitá. The Brazilian passage is made possible by three new iron-plated monitors built at Rio de Janeiro and armed with 70-to 120-pounders. Valiant Paraguayan bogavantes paddle their canoes to make a bold assault on the lead monitor, leaping to the Alagoas’s deck and tearing at the hatches with their bare hands until bullets from the turret rake them down.

Invested by land, Humaitá surrenders six months later, and the Allies advance toward Asunción. President López sets up new lines in the Lomas Valentinas hills below the capital, where the Allies are bent on dealing the death blow to his army. At Avaí, 22,000 men clash in a four-hour battle in which the Paraguayan battalions are annihilated, but 4,200 Brazilians and Argentinians also go down.

Antônio Paciência is a stretcher-bearer at Avaí. Long past midnight, he is with two comrades, Tipoana, a Pancuru Indian who goes by the nickname of “Urubu,” and Henrique Inglez, a mulatto, the son of an English actor who has lived in Brazil for forty years. The trio is adept at finding spoils as they move across battlefields thickly sown with friend and foe.

The first Allied troops enter Asunción on January 1, 1869, greeted by several thousand poorer Guarani and mestizos, and for every man, four or five women, emaciated and almost nude. The ravaging of the city begins as rumors spread of the hidden fortunes of El Presidente and La Lynch; night after night, the sky glows with fires set by rampaging soldiers. On January 14, the marqués de Caxias, issues Order of the Day Number 272: “The war has come to an end.” Seventy-two hours later, Caxias collapses during a thanksgiving service and relinquishes his command.

In April 1869, Hadley Tuttle and thirty-nine raiders burst through the valley of Pirayu from their base camp at Cerro León east of Asunción. They’re aboard an armored train with two sandbagged flatcars pulled by Piccadilly Pride, a rickety locomotive that served on the Sevastopol-Balaklava line. They head for the headquarters of the new Brazilian commander, Prince Louis Gaston, Comte d’Eu, son-in-law of Emperor Pedro II.

López has raised a new army of 13,000, drawn from every corner of Paraguay. His arsenal has cast eighteen new field guns and stockpiled 600,000 shells. López rises to combat, too, those suspected of plotting to overthrow the dictator. These foes include his older brother, Venancio; his sisters; and, his mother, Dona Juana López. Throughout the war, Eliza Alicia Lynch has remained totally loyal to El Presidente.

Piccadilly Pride makes a smooth run to the Brazilian camp, where her field guns open up setting fire to everything within range. When the Brazilians begin to retaliate, Hadley Tuttle backs up beyond a bridge, which they blow up before racing for home. They’re two miles from the head of Pirayu valley, when three hundred Rio Grande do Sul cavalrymen catch up with the train charging beside the flatcars with lance and sabre. Other horsemen storm ahead to lay a log barrier across the rails into which Piccadilly Pride rockets, her overheated boiler blowing with a terrific explosion.

On August 16, the Brazilian sledgehammer is raised on a plain called Acosta Ňu, where comte d’Eu brings four divisions with twenty thousand men to face 4,300 Paraguayans. Colonel Clóvis Lima da Silva, released from captivity; Fábio Alves Cavalcanti; and Antônio Paciência are all witness to what happens on this wintry day. At 7.a.m. Clóvis’s guns open fire; by mid-morning infantry attacks begin with thousands advancing on the Paraguayan trenches. From the north, the first blocks of cavalrymen are unleashed from a body of eight thousand. For nine hours the Paraguayans withstand the onslaughts before they are overrun. “Ce’st magnifique!” said comte d’Eu. “Ce moment de la victoire!”

The soldier’s holding the plain at Acosta Ňu bought precious time for Francisco Solano López who escapes with a vanguard of two thousand. Behind them they leave two thousand dead, eighteen hundred are boys, some just children of six and seven lying beside flintlock muzzle-loaders.

López eludes his pursuers for six months. He is trapped at Cerro Corá, “The Corral,” 230 miles northeast of Asunción, with five hundred men and boys. And here, too, is Eliza Lynch and their five sons. López orders Eliza to flee in a carriage with four of their offspring, the fifth son leading her escort, fifteen-year-old Colonel Juan Francisco López. A Brazilian kills Juan when the carriage is surrounded and he refuses to surrender. At the Corral, a battle lasts fifteen minutes, before a lancer spurs his horse toward El Presidente and slashes his abdomen. On a high bank a mile north of the camp, López is helped off his horse by his staff. Brazilians find him sitting in the mud next to a small palm. Shot at point-blank range, “I die with my country,” are his last words.

In five years of war, ninety percent of the men and boys of Paraguay are slain. The Allies lose 190,000 men, the majority of them Brazilians.

{SPOILER ALERT -- This is a synopsis of a novel that runs to 340,000 words. Nonetheless, the PLOT SUMMARY contains incidents and scenes that reveal key elements of the story.]

Dr. Fábio Alves Cavalcanti is on the platform at the Teatro Santa Isabel in Recife on a Sunday in November 1884, when abolitionist Joaquim Aurélio Nabuco denounces slavery in Brazil. A Free-Womb law offered conditional liberty to slave children born after 1871 but only 118 of 400,000 of these ingénuos (innocents) have been freed. Only the northern province of Ceará has declared itself free of slavery, its abolitionists spurred on by a strike of Fortaleza’s boatmen who refused to ferry out to ships slaves who were to be transported to the south.

Rodrigo Cavalcanti, older brother of Fábio, is senhor de engenho of Santo Tomás, where eighty-five slaves labor alongside 180 families of agregados (“associates”) and gangs of itinerant cane cutters. Rodrigo agrees that slavery must go, but wants it to die out gradually, as the Free-Womb law provides; with a million slaves on the coffee plantations of the south, he fears a bloody convulsion that could threaten the monarchy, already challenged by Republican agitators. Dom Pedro II is 59, his health impaired by diabetes and malaria; Princess Isabel is popular but her French husband, Comte d’Eu, considered likely to be instrumental in a third empire.

Fábio’s home and medical practice are at Boa Vista, Recife, and his life there a total break from the patriarchal regime of the engenho. He sees an evil for Brazil in the vast landholdings that keep hundreds of impoverished families tied to large estates like serfs. Fábio’s concern for the landless mass is genuine. But each time he returns to Santo Tomás, he has the feeling of coming home. He is in Rodrigo’s debt for the welcome given him and Renata on their return from Paraguay. They have three children, Ana and Amalia, and a son, Emílio.

Rodrigo’s youngest son, nineteen-year-old Celso, is living at Fábio’s home in Boa Vista, while attending Recife Law School. The house is open to a regular stream of abolitionists and freemasons, from whom Celso gets ideas that make Rodrigo fear he is an incipient “anarchist.” A groundless concern though Celso does harbor a secret passion to be a priest.

Celso joins six men who meet in secrecy in a house on the rua da Cruz in Recife’s old quarter. They are members of Clube do Cupim, which takes its name from the cupim, the termite, and its motto, too: Destroy without Noise. The club helps slaves fleeing from the plantations of Pernambuco to the coast and by sea to Ceará. The chairman of the Termite Club is “Agamemnon de Andrade Melo,” an actor popular with audiences at the Teatro Santa Isabel. He is none other than Henrique Inglez, the younger, who prowled the battlefields of Paraguay robbing corpses with Tipoana and Antônio Paciência.

Henrique Inglez tells Celso that forty “pineapples” – code word for fugitive slaves – are ready to flee the district of Rosário. Thirty-two are from Engenho Santo Tomás. Rodrigo is in Europe, buying machinery for a sugar mill, leaving Celso’s brother, Duarte, in charge of the plantation. At a rendezvous on the old road to Rosário, Celso meets Jorge Chinela, “Slipper George,” a Cupim agent. They begin a perilous 75-mile journey to the coast traveling by night. By day, they hide the slaves at an abandoned engenho central which is searched by mounted capangas from Santo Tomás and other plantations. The henchmen leave without finding Celso, Slipper George and the fugitives in the cavernous mill. Three hours later Duarte Cavalcanti rides up with the Guarda Nacional, but they, too, fail to trap the runaways. Four nights later, Celso and Slipper George make a final dash to Itamaracá Island, where the slaves are ferried to a vessel that takes them to freedom.

At the inauguration of Usina Jacuribe, Rodrigo Cavalcanti celebrates the launch of a factory to process canes from Rosário’s plantations. He sees the usina as ultimate triumph for generations of Cavalcantis in the valleys of Santo Tomás and the promise of maintaining their vast latifundia in perpetuity.

Bábá Epifánia, a BaKongo slave manumitted according to terms of Ulisses Tavares da Silva’s will, belongs to the caiphazes (named after the Jewish high priest Caiaphas),militant abolitionists in São Paulo province. In October 1887, at the quilombo of Tamanduatei-Mirim, eighty miles west of Tiberica, Epifánia and Nô Gonzaga plot the flight of one hundred of Itatinga’s 370 slaves.

Firmino Dantas da Silva runs the fazenda on the Rio Tietê, with its 750,000 coffee trees, cane fields, sawmills and herds of cattle. At his side is Aristides Tavares, the son of Ulisses Tavares and Teodora Rita. (The baroness lives in Paris, a vivacious belle among a glittering colony of Brazilians.) Firmino is married to Teodora Rita’s sister, Carlinda Mendes, plump, domestic and deeply superstitious. Epifánia, a wet nurse to the da Silva children, is a sorcerer, whose arts of magic Carlinda relies on for protection against the evil eye of Exú. Firmino Dantas is himself bewitched by Jolanta, the poet Amêrico dos Santos’s daughter, who he keeps as mistress at Tiberica.

Epifánia drugs the overseers of slave gangs clearing the jungle at Itatinga. Nô Gonzaga and the caiphazes escort one-hundred-and-twenty-eight slaves to a railhead six hours’ away. When their flight is discovered, Aristides rides to Tiberica to summon Eduardo da Silva, Colonel Clóvis’ oldest son, who is chief of police nicknamed “Cockroach Killer” for his ruthlessness. His second-in- command is Cadmus Rawlings, a Confederate veteran who came to Brazil after the Civil War. Sergeant Rawlings lives with a dark-skinned mulatta and their three children but has no trouble reconciling his domestic situation with his abhorrence of Negroes.

The police find the São Paulo train stopped half-an-hour away from the railhead, the engineer beaten into admitting that they are waiting for Itatinga’s runaways. The passengers are ordered out of the coaches and Aristides sees his old wet nurse among them. Cadmus Rawlings raises his riding whip to Baba Epifánia, but Aristides stops him. Nô Gonzaga and his men show themselves, rising up on top of the coaches and in the grass beyond. Eduardo da Silva fires first and is shot dead. Aristides is wounded. Cadmus Rawlings empties his six-shooter, as other Tiberica policemen drop their weapons and flee. Gonzaga’s troop give a cheer as Rawlings rides off with the corpse of Eduardo da Silva and the young fazendeiro, who is in no danger. Twenty-three slaves are caught on the flight down the Serra do Mar to Santos, but the rest join 4,500 runaways at Jabaquará quilombo.

On Christmas Day, 1887, Firmino Dantas and Aristides offer 203 remaining slaves a small wage for the next harvest and freedom in two years. By the end of the week, all but thirty-three slaves abandon Itatinga, a scene repeated through the “Black Triangle” of Sao Paulo, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro. On May 13, 1888, Princess Isabel acts as regent for Dom Pedro who is in Europe, signing “The Golden Law” that abolishes slavery in Brazil. That same year, 100,000 Italian immigrants arrive to work in the coffee groves, 115 colonos welcomed to Itatinga by Firmino and Aristides.

On the Isla Fiscal in Rio de Janeiro’s Guanabara Bay, 4,000 guests attend a fantastic ball given by Emperor Pedro II on November 9, 1889. Rodrigo Cavalcanti, Baron of Jacuribe, is confident that the monarchy will endure. Lieutenant Honôrio da Silva, an army officer like his father Clóvis, is a republican and believer in the Positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte, with its motto of Order and Progress. Aristides is at the ball with his wife, Anna Pinto; he sees a tottering empire brought to the brink by dissension between Pedro’s ministers and the military. The Revolution of November 15 takes place with a single shot fired as the Bragança dynasty is swept away and the United States of Brazil proclaimed. Two days later, Aristides and Honôrio are on the palace square at 3.00 A.M. when Dom Pedro and his family leave for Europe. ”Alferes Silva Xavier lit the torch of freedom one hundred years ago,” says Honôrio. “God knows, Tiradentes is watching.”

Colonel Clóvis Da Silva marches with 5,000 troops sent to crush an uprising in the backlands of Bahia, 250 miles north-west of Salvador. Antônio Conselheiro – “The Counselor” – is an anchorite who predicts the end of the world in 1899 and sees a New Jerusalem where Dom Sebastião, the Portuguese king who fell in battle against the Moors in 1578, returns to rule the Faithful. Conselheiro attracts 20,000 followers to Canudos, variously described as fanatics, bandits and monarchists. Three earlier expeditions are repulsed with heavy loss of life.

Clóvis positions his guns on a ridge below Monte Favela four thousand feet from Conselheiro’s crude citadel with its labyrinth of streets and alleys and massive unfinished church. On their first night at Canudos in July 1887, General Artur Oscar’s column is attacked by 3,000 rebels. Clóvis hears a cry that sends a chill down his spine: “Macacos! Macacos! Macacos!” The same insult hurled by Guarani on the bloody fields of Paraguay.

It is Antônio Paciência who mocks the gunners. Returning to Fazenda da Jurema after the war, he was overjoyed to find his mother, Mãe Mônica, alive. Acknowledged as a bastard son by Heitor Ferreira, Antônio joined the vaqueiros of Jurema and served as a jagunço, a clan gunman. In 1882, Chico Tico-Tico, his best friend, is murdered. Antônio is implicated when Chico’s son, Zé Cavalcente, shoots the brother of his father’s killer; Antônio is sentenced to eight years’ hard labor. He escapes into the sertão and finds a home with Vivaldo Maria Marques, a salineiro (harvester of salt.) Antônio joins Marques as a salt trader and marries his daughter, Rosalina, with whom he has two sons, Teotônio and Juraci Cristiano.

In 1893, Antônio and Vivaldo settle at Canudos with their families, personally invited by The Counselor for their salvation. Antônio is one of several hundred Paraguayan war veterans and emerges as a commander. Zé Cavalcante’s gang of bandits rides with the rebels cutting a bloody swathe through the caatinga in ambuscades of government troops.

The morning after the surprise attack on Monte Favela, Clóvis and his gunners begin a lethal bombardment that lasts thirty minutes before a counterattack brings hundreds of rebels to the ridge. In the hand-to-hand fighting to save his guns Clóvis is mortally wounded. Five miles away Antônio Paciência and Zé Cavalcente rout General Oscar’s supply train.

Padre Celso Cavalcanti, from the archbishopric at Salvador, ministers to 817 wounded on Monte Favela. In the years since his work with the Termite Club, Celso has not lost his concern for the oppressed. He supports the Church’s fight against fanaticism but is aware of intolerable conditions among the sertanejos that drive them to accept the promises of false prophets like Conselheiro. Celso comforts Major Honôrio da Silva, who is with Cláudio Savaget’s Second Column, but the lancer dismisses the priest’s compassion for an accursed tribe.

God’s Thunderer, a Whitworth siege gun, and eighteen other pieces pound the lower town. Antônio’s son, Teotônio, tags along with a squad sent to destroy the Whitworth and dies in a hail of bullets. Rosalina perishes in a rain of shells from a mile-wide arc of guns. In the caatinga beyond the beleaguered citadel, Honôrio da Silva’s company adopts the tactics of the jagunços flushing out bandits in the thorn-studded scrub. Zé Cavalcante’s band are caught in the open, their leader himself killed. Marshal Carlos Machado Bittencourt, minister of war, takes over the campaign. The siege lines tighten, outlying barrios overrun, the church towers knocked down in the incessant bombardment.

Sickness rages through the town. Antônio Conselheiro is one of the victims, dying two days before the investment of Canudos is complete. The sertanejos continue to resist, Major Honôrio’s lancers storming earthworks where defenders fight to the last against the rush of steel and fire. Padre Celso finds a confidant who shares his views about the abandonment of an oppressed class of Brazilians beyond reach of civilization: Euclídes da Cunha, a military man turned correspondent for the Estado de São Paulo.

Two thousand government troops storm the plaza and raise the green and gold banner of Brazil over the battered ramparts of New Jerusalem. A three-hour ceasefire is granted to allow women and children to cross the lines. Antônio Paciência’s leads Juraci Cristiano to safety, Celso Cavalcanti taking the boy from him with a promise that he will be unharmed. Three days later, Antônio falls with the last defenders of Canudos.

Juraci Cristiano is placed in an orphanage at Salvador.

Celso returns to Recife from the Bahia in 1903 as an assistant to the bishop of Pernambuco. Henrique Inglez is at Dr. Fábio house when Celso speaks about Juraci and his father at Canudos. Henrique tells them of his time with Antônio Paciência in Paraguay. Fábio and Renata offer whatever help Juraci Cristiano needs and pay for him to go to the Marist’s school at Olinda. In December 1906, Celso collects the boy from school and takes him to Engenho Santo Tomás, where he spends the Christmas holidays with the Cavalcantis, welcomed into the Casa Grande by Baron Rodrigo. Celso knows this is only one child, but takes joy in imagining that others like Juraci Cristiano will find opportunity to flourish in Brazil. The land of the future. Their land.

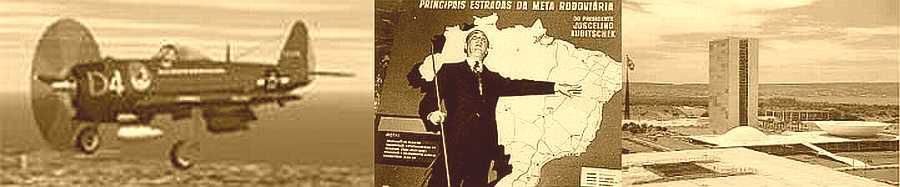

Roberto da Silva is imbued with the daring and drive of his bandeirante ancestors. Fifteen when he first took off from a dirt strip outside Tiberica, in 1944 he flew with the First Pursuit Group on missions in northern Italy in support of the “Smoking Cobras,” a Brazilian force of 25,000 men attached to Mark Clark’s Fifth Army, the only South American soldiers to go to war alongside the Allies. Roberto is a civil engineer, who heads up the da Silva’s construction company in São Paulo, one of twenty-four family-owned enterprises in addition to Itatinga, where four million coffee trees flourish on the red earth above the Rio Tietê.

On April 19, 1956, Roberto visits his father, Amílcar da Silva, son of Aristides Tavares, at Itatinga bringing news of a bold move by the new president, Juscelino Kubitschek: Brazil is to have a new capital in Goiás on the high central plateau. Amílcar dismisses Brasília as the crazy idea of a new pharaoh. Roberto embraces the plan as a beacon for Brazil that will end the inertia that has kept Brazilians clinging to lands near the coast and reverse a tidal wave of poor swarming into the favelas (taken from “Monte Favela” at Canudos) of Rio and other cities.

In the valley of Santo Tomás, Anacleto Pacheco has cut cane for forty-four years. Pacheco has fathered twenty-three children, twelve of whom died, most in infancy. Raimundo, twenty-three, is the only one of Anacleto’s grown sons working on the plantation. The family rents a small patch of land from the Cavalcanti brothers, Durval and José, who run Usina Jacuribe, which processes cane from every plantation in Rosário district.

In September 1958, Raimundo Pacheco meets Eduardo Corrêa of the Ligas Camponêsas (Peasant Leagues,) an agrarian reform movement.

Raimundo is influenced by Corrêa’s talk of ending the cambão, the “yoke,” whereby one day a month families like the Pachecos are obliged to labor without pay as partial recompense for use of the land they occupy. Anacleto has heard Senhor Durval denounce the Leagues and threaten to evict any worker spreading their poison in his valleys.

Dr. Juraci Cristiano runs two clinics at Santo Tomás, one at the old Casa Grande, which has been boarded up for twenty years. With the support of the Cavalcantis, Antônio Paciência’s son studied medicine and established a practice at Recife. Juraci’s own radical views led him to the Communist-backed Alianca Nacional Libertadora (ANL,) which caused a rift between him and Alvaro Cavalcanti, father of Durval and José. When the ANL was banned by President Getúlio Vargas, militant Communists staged an uprising which was suppressed. Juraci took no part in the insurrection but was briefly jailed with the instigators. The Cavalcantis eventually relented and allowed the “old Communist” to return to their valleys.

Anacleto Pacheco begins to understand the slavery of the “yoke.” He confides in Dr. Juraci, who agrees that the cambão is a curse but warns Pacheco not to challenge Durval Cavalcanti. Change is bound to come, he says, but it will be slow. – How slow? He wonders. “A century from now? When Raimundo Pacheco and his sons are in their graves, with their calloused hands crossed on their chests?”

Seven tenants led by Anacleto and Raimundo ask the Cavalcantis to abolish the cambão, the delegation hoping for a sympathetic hearing from Senhor José, known to show concern for the cane workers. Durval rejects the appeal and orders Anacleto and his family summarily evicted, because of their contact with the Peasant Leagues.

Joazinho Villa Nova, head capanga, and his enforcers load the Pachecos’ belongings onto a truck and dump the family on the Rosário road. Raimundo is injured in a separate confrontation and taken to Juraci Cristiano’s clinic, where Durval finds him. Cavalcanti rejects Juraci’s bid for mercy for the Pachecos, but orders Joazinho to leave Raimundo in the doctor’s care. The rest of the family is headed for the caatinga, where Anacleto’s half-brother keeps goats. Raimundo chooses to ride the pau-de-arara, the “parrot’s perch,” roosting in the back of a truck heading for the site of Brasília, where there is work for the sertanejos. He looks for the last time on the green valley where he was born. “Yes, son, for the Cavalcantis, this is Canaan,” Juraci Cristiano says.

In March 1959, Shavante Indians attack road builders on a 232-kilometer section of the Brasília-Belém highway under construction by Roberto da Silva’s company. Roberto and Bruno Ramos Salgado of the Serviçio de Proteção dos Indios (SPI) fly to a camp at Kilometer 189, deep in the Amazon rain forest. Salgado is half-Parési, descended from “Mad Murilo” Salgado, a notorious Indian hunter; his own father, Izaias, butchered Caripuna and Pacaas Novas who harassed men building the Madeira-Mamoré railroad. Izaias was himself pacified when he joined the Telegraphic Commission under Colonel Cándido Rondon, who forbade the slaying of Indians, with the credo, “Die if necessary, but never kill.” Bruno follows this example with the SPI, which Rondon founded.

An expert tracker, Bruno leads Roberto and two workers into the forest beyond Kilometer 189. At a river crossing, a young Shavante warrior appears on the bank with a long bow and war club. Unarmed and gesturing friendship, Bruno goes to the Shavante, who is quickly joined by four others. Salgado begins an impromptu dance, leaping and running along the riverbank; Indians speed along beside him, symbolic of the great log races their people run. The tension diffuses, the full band of nineteen emerges, accepting gifts Roberto offers, mirrors, fish hooks and other trinkets. Bruno, who works with Shavante established in settlements along the Rio das Mortes, offers to locate the band at one of the SPI posts. In the morning, the Shavante are gone.

In 1960, Roberto and his family attend the inauguration of the new capital. Senhor Amilcar doesn’t forget his skepticism about “pharaoh” Juscelino’s mirage in the desert. His wife, Dona Cora, laments that her old friend, Max Grosskopf, a renowned São Paulo restaurateur, is operating “Chez Maximilian” in a favela, as she sees Cidade Livre outside Brasilia, a gaudy neon-lit antidote to the precise vision of Oscar Niemeyer and Lucío Costa. Mariette Monteiro da Silva, Roberto’s nineteen-year-old daughter, is thrilled by Brasilia sharing her father’s a grand, magnificent gesture toward the future.

On April 21, 1960, tens of thousands of candangos – a Kimbindu word applied to 60,000 Brazilians who built the new capital, simply ‘a man who works hard’ – parade along the mall toward the Plaza of the Three Powers. Roberto walks among them, as does Raimundo Pacheco, who came on the parrot’s perch. President Kubitschek inaugurates the capital of the United States of Brazil, in honor of Lieutenant Joaquin José da Silva Xavier, who gave his life for the liberty of his people. At a window on the twentieth floor of the twin skyscrapers, Amilcar da Silva gazes out, not at the gleaming city, but far in the distance to where the cerrado is darkening:

This vast sertão, not only over the next hill or across the next river, but deep within the soul. A call to Paradise or Hell for our forefathers. Were they out there, now, Amador Flóres da Silva and Benedito Bueno – all those who had opened the way for this conquest? Were the old bandeirantes gazing back in awe at this city – this El Dorado they had sought for so long?

Tóninho

Padre Antônio “Tôninho” Paciência, Juraci Cristiano’s grandson, is the priest at Magdalena, poorest parish of Rosário. In March 2000, the Landless Workers Movement (MST) holds a meeting in the church hall at which thirty families led by sharecropper Luis Alves de Sá declare themselves ready to march with the landless army. Ten days later, Padre Tôninho and MST organizers lead ninety-two adults and sixty-eight children, who invade Engenho Santo Tomás. They set up camp on a 900-acre parcel, originally the site of a Tobajara clan’s malocas, later the stamping ground of the degredado Affonso Ribeiro’s tribe. The Cavalcanti’s never grew a stalk of cane here.

Clodomir Cavalcanti and his wife Xeniá Freitas de Melo have restored the Casa Grande, where Padre Tôninho occasionally officiates in the chapel and enjoys the same welcome as shown Dr. Juraci. Clodomir is president of the local Farmers’ Association, an outspoken opponent of Sem Terra (“Without Land”) but condemns landowners who take the law into their own hands and whose hired gunmen have killed 1,000 people in a decade. He tells Tôninho he will go to court to have the squatters evicted, but can’t guarantee what other owners will do.

“Affonso Ribeiro,” as the MST camp is called, withstands a four-hour siege of terror by justiceros armed with rifles and dynamite bombs. Padre Tôninho is ambushed by gunmen, his VW shot up and wrecked. Clodomir Cavalcanti rescues him from the overturned car, miraculously unhurt, and takes him to the Casa Grande. From the window of the great house, Clodomir can see the patch of jungle with the new settlement of Affonso Ribeiro and the people who came to seek a new country, not for the great men of the earth alone but all Brazilians.

Mariette da Silva Prado

Mariette da Silva Prado belongs to the powerful Clube das Monções, where a statue of Benedito Bueno da Silva dominates the entrance to what is practically an institution of Tiberica’s men, who still bristle at the entrada of women like Dona Mariette. Roberto’s daughter is bold and tough, and tireless in pursuing her goals that include running the Casa dos Meninos, a children’s shelter founded by her in Riachuelo, the biggest of Tiberica’s favelas. The Casa cares for 200 boys and girls, among them forty meninos da rua, from the city’s 3,000 children of the streets.

Mariette became first woman mayor of Tiberica in 1987, winning as candidate for the Workers’ Party against Oscar Amaral Dutra. Dutra was hailed for the “miracle” of Tiberica that saw the município advance to a bustling manufacturing center of 190,000. Dona Mariette’s two terms were spent fighting waste and corruption that made Tiberica a cesspool of bribery during the old chefe’s twenty-four-year rule.

Roberto, retired to Itatinga, still one of the finest and richest coffee plantations in the world, was not surprised when his daughter took up the banner of the Workers’ Party. When she was in her twenties, Mariette was with the right, an organizer of the “March of the Family with God for Liberty,” in São Paulo on March 19, 1964 to protest the government of João Goulart. Twelve days later the army launched a coup that instituted a military dictatorship that ruled Brazil for twenty-one years.

In 1965, Marietta was traveling in Europe, when she met Gilson Prado, a student at the London School of Economics. Married in 1966, they set up home in São Paulo, where Gilson lectured at the University of São Paulo. In March 1973, Prado was picked up by DOPS, the Department for Political and Social Order, because of involvement with the militant Catholic Action. Eleven days after his abduction by the political police, Gilson’s body was turned over to his widow. The official autopsy claimed that Gilson died by hanging in his cell, but a fellow detainee revealed that he was perversely tortured for three days. Mariette herself came under suspicion. Roberto wanted his daughter and two grandsons to leave the country, but she refused to go.

At the Casa das Meninos on April 12, 2000, Marcos Gonzaga, who shines shoes outside the five-star Paraupava Hotel, seeks help in finding his sister Rosalie. She is a runaway who has been seen with the daughter of Pedro Dominguez, king of Tiberica’s garbage dump. Marcos is frightened to approach Pedro Rei – “King Peter” – who controls a malodorous empire where men, women and children mine the landfill like garimpeiros looking for gold.

Dona Marietta goes with Marcos to Pedro Rei, who suggests they look for Rosalie and his daughter in Ipêlandia, a suburb next to Tiberica’s factories teeming with bars and brothels. A street kid who knows Teresa Dominguez leads them to a vacant lot with an abandoned bus, where the girls take the men who pay them for sex. Teresa refuses help, but thirteen-year-old Rosalie who is obviously pregnant lets Marcos take her hand and lead her outside. In Tiberica in four months’ time Rosalie’s child will be born in the favela. It will give its first cry in an unjust country. Brazilians like Mariette da Silva hear that cry.

Bruno Ramos Salgado

“The Old Devil” is eighty years old in 2000, long retired from the National Foundation for the Indigenous (FUNAI) successor to the Indian Protection Service (SPI.) Bruno Salgado lives at the tiny village of Kaimari in the Serra dos Paresís, a living hero who risked his life to save the forest people of Rondonia. He remains a scourge of interlopers, especially illegal loggers who he despises for destroying the rainforest.

Ten years earlier, rival tree cutters killed three men near Kaimari, including Edson Monteiro, a Pataxó from the state of Bahia, whose Indian name was Apurinã. Salgado found a lone survivor in the jungle camp: Tajira, Monteiro’s four-year-old son, whose father brought him to the jungle after his mother died. The Old Devil’s friends at FUNAI could not locate the boy’s relatives and the child stayed with Salgado, a blessing to his protector who has no children of his own.

In April 2000, Bruno resolves to find the boy’s people, knowing no one will be there for Tajira when he is gone. The pair leave Kaimari for Pimento Bueno, the nearest town, where they take the Porto Velho-Cuiabá bus, and from there to Brasília, and finally across the highlands of Minas Gerais to the coast. Their destination is Santa Cruz Cabrália, fifteen miles north of Porto Seguro, where a group of Pataxó Indians live. They arrive on April 25, 2000 amid celebrations to mark the 500th anniversary of the Portuguese captain, Pedro Álvarez Cabral’s dropping anchor off the islet of Coroa Vermelho.

On the eve of a commemorative mass at Coroa Vermelho, Bruno and Tajira go to the house of Ticua Mattos, a grand old dame of the Pataxó, who takes one look at the boy and declares him to be the son of Apurinã, who went to cut wood in Mato Grosso and never came back. Ticua sends for Obajara, Tajira’s uncle, who is astounded by the news about his nephew, sad that the boys’ parents are dead, but joyful that he is back with his people.

The Old Devil stands at the edge of the huge crowd, a blustery wind bending the palms at the altar in front of a towering Cross. The mass is attended by 300 bishops and fellow clerics celebrating the hour in which Friar Henrique of Coimbra prayed with Cabral’s men and the Tupiniquin who were there to rejoice with the Long Hairs. Pataxó, Shavante, Nambikwara, Yanonami and Indians from all over Brazil listen solemnly as descendants of the discoverers ask forgiveness for the sins and errors of five centuries. There is no Tupiniquin to hear the apologia.