DESCRIPTION

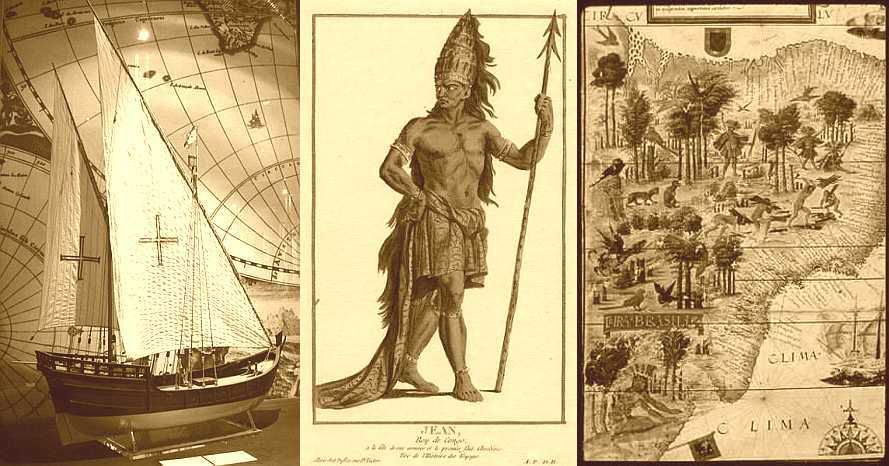

Brazil is the first work of fiction to depict five centuries of a great nation's remarkable history. With a stunning cast of real and fictional characters, this unforgettable epic unfolds in South America, Africa and Europe.

Lacing the tale together are the shifting fortunes of two dissimilar Brazilian families. The Cavalcantis are among the original Portuguese settlers and carve a gracious plantation out of the Pernambuco wilderness of the north - the classic Brazilian casa grande, vast, powerful, and built with slave labor. The da Silvas of mixed Portuguese and Tupiniquin blood are a spirited family of dreamers, pathfinders, soldiers and entrepreneurs. For generations, they set their eyes on El Dorado, a vision of wealth ultimately achieved in a huge financial empire that makes them power brokers in the new Brazil.

Brazil is an intensely human story, brutal and violent, tender and passionate. Perilous explorations through the Brazilian wilderness...the perpetual clash of pioneer and native, visionary and fortune hunter, master and slave, zealot and exploiter...the thunder of war on land and sea as European powers and South American nations pursue their territorial conquests...the triumphs and tragedies of a people who built a nation covering half the South American continent...all are here in one spellbinding saga.

The principal characters, both real and imaginary, are hard to forget. Among them: the great Indian warrior-chief Aruana; Amador da Silva, a bandeirante 'flag-bearing' pioneer and emerald hunter; Secundus Proot, a Dutch artist-adventurer in the Amazon; Black Peter, a freed African slave who takes murderous revenge on his persecutors; Antonio Paciencia, a brave soldier and humble hero of the landless; Francisco Lopez, doomed and gallant president of Paraguay; Anthony the Counselor of Canudos, visionary rebel of the backlands.

The result is an unsentimentalized historical novel that combines adventure with an impressive level of research and depicts Brazil free from the eternal stereotypes

An Illustrated Guide to the Novel offers a wealth of images and maps and access to the writer's private journal bringing a unique insight into the novel and its creativity.

"Uys has accomplished what no Brazilian author from José de Alencar to Jorge Amado was able to do. He is the first outsider with the total honesty and sympathy to write our national epic in all its decisive episodes. Descriptions like those of the war with Paraguay do not find in our literature any rival capable of surpassing them and evoke the great passages of War and Peace." - Professor Wilson Martins, Jornal do Brasil

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The novel begins in May 1491 at the malocas of a Tupiniquin clan in the Atlantic rain forest near present-day Porto Seguro. On the eve of his initiation into manhood, Aruanã faces the problem of a father, Pojucan, who has made himself an outcast among his people. Captured by an enemy clan, Pojucan refused to submit to the ritual slaughter of prisoners, fleeing back to the Tupiniquin, who greeted his return as an act of cowardice.

Naurú, the village pagé, demands Pojucan’s death. Before this sentence can be executed, Aruanã gets caught in the conflict between his father and the shaman and is despised by his peers and playmates.

Pojucan has one ally in the village: Ubiratan, a warrior of the distant Tapajós, who has ended up among the Tupiniquin after capture and flight from a northern tribe. Pojucan proposes that he accompany the Tapajós on a journey back to his own people. They’re ready to leave when Aruanã, scorned and humiliated by Naurú, joins them.

The trio travel through the rain forest crossing lands that will encompass Brazil. Pojucan dies on the journey, slain by two jaguars on a floating island in a great stream. The others reach Ubiratan’s village on the Mother of Rivers, which we know today as the Amazon. Aruanã spends several years with the Tapajós, growing to be a fine warrior and encountering Tocoyricoc, an ancient wanderer who drifted to these parts from the realm of the Inca.

Through Tocoyricoc, Aruanã sees that an existence among strangers cannot replace a life with his own Tupiniquin, and finally, he returns to the village of his forefathers. Accepted back, he exults in the very ceremony that his father despised: The slaying of captives taken in war and the cannibal rite that follows. In contrast, there are moments of tenderness shown at the birth of his first son with Juriti, “The Dove,” on the eve of the arrival of the Portuguese.

Nicolau Cavalcanti is second-in-command of one of three ships sent from Lisbon to patrol the Brazilian coast against French corsairs in 1526. They anchor in the bay near the Tupiniquin village, where Aruanã is an elder. French interlopers have established a brazilwood trading post in the area.

A quarter-century since Aruanã witnessed the arrival of Pedro Álvares Cabral’s ships, the Portuguese first showed little interest in Terra da Santa Cruz. Their fortune lies in the Conquest of the Indies and the Arab spice routes. Nicolau Cavalcanti was schooled in that violent arena, rising from cabin boy to gunner to officer during the command of Afonso d’Albuquerque.

The Cavalcantis, like many Portuguese families of the 14th and 15th centuries, originally hailed from another locale – Florence—settling in Portugal on the eve of Prince Henry, “The Navigator’s,” great explorations. Nicolau’s family is well-placed with an estate at Sintra but lacks royal connections.

Nicolau leads a shore party that destroys the French settlement. Aruanã’s Tupiniquin watch the attack, and though they enjoy good relations with the French, do nothing to assist them. Their inaction is prompted by Aruanã’s son-in-law, Affonso Ribeiro, a degredado, an exile banished for crimes committed in Portugal. Nicolau visits the Tupiniquin malocas, where he is entranced by Ribeiro’s daughter, Jandaia, and makes love to her.

Le Tigre, “The Tiger,” a Dieppe corsair engages the patrol and sinks two ships. Nicolau’s vessel escapes, but its captain is killed, and command passes to Nicolau. Undermanned, damaged, he sails across the Atlantic to a Portuguese refuge on the Congo River. He visits the lands of the Mani Kongo, king of the Bakongo, a Christian convert who goes by the name of Affonso, Duke of Nsundi, and models his court on that of Lisbon.

Nicolau cannot be blamed for the defeat at Porto Seguro and returns safely to Lisbon, but the affair reduces his chances of advancement. He writes a memorandum to the king, in which he argues that the French will not be routed until a proper base is established in Brazil.

In 1533, King João III creates hereditary captaincies providing extensive land grants along the Brazilian coast: Duarte Coelho Pereira, a Goa veteran, is one of the donatários.

Nicolau and his wife, Helena, and their sons, Pedro and Henriques, sail with Duarte Coelho to Pernambuco, where they settle at Iguarassu. The local Indians, friendly at first, turn hostile when they find more is expected of them than occasional logging of brazilwood. Sporadic conflict grows. Nicolau travels to Porto Seguro, where he persuades Affonso Ribeiro to move to Pernambuco with his family, among them Salpina, Aruanã’s daughter, and Jandaia, who becomes Nicolau’s mistress.

In 1536, Nicolau and Ribeiro discover a lush valley two days’ journey from Dom Duarte’s capital of Olinda. Nicolau gets a grant of twelve square leagues, almost 75,000 acres – to a man from Portugal, a kingdom in itself.

Helena gives birth to Tomás, the first of these Cavalcantis born on Brazilian soil. Jandaia, too, brings her lover a son. Nicolau’s joy is tempered by the departure of Henriques, who returns to Portugal with no vision of prosperous valleys planted with sugar cane.

Enslaved Potiguara and Caeté, “who can be bought for the price of a sheep,” prove reluctant field workers. Nicolau and other planters petition King João for slaves from Africa. In 1545, a caravel from Mpinda brings sixty Africans from the Congo to Pernambuco. Cavalcanti buys three men and three boys for his plantation, which he calls Engenho Santo Tomás.

At a festa at Affonso Ribeiro’s malocas, a degredado kills the son of a local chief, sparking an uprising against the colony. Forty warriors penetrate the valley of Santo Tomás. Pedro, Nicolau’s first-born, is slain. The engenho is besieged by Caeté warriors. Helena and Jandaia stand shoulder to shoulder to drive off a surprise night attack. A relief force led by Affonso Ribeiro rescues the beleaguered settlement, which is abandoned. As Nicolau leaves, he sees smoke enveloping the stockade, but vows to return to Santo Tomás.

Padre Inácio Cavalcanti, Nicolau’s nephew, arrives at Bahia de Todos os Santos, Bay of All Saints, four hundred miles south of Pernambuco in March 1549. He is one of six Jesuits under Padre Manuel de Nóbrega accompanying Tomé de Sousa, first governor-general of Brazil. A year later, Nóbrega orders Inácio to travel to Pernambuco, where he visits his uncle, Nicolau Cavalcanti.

Engenho Santo Tomás is one of the captaincy’s most promising plantations with extensive cane fields and an ox-powered sugar mill. The thirty African slaves are a burden to Inácio but not overwhelmingly so; such servitude has been commonplace in Portugal for more than a century. But he is shocked by the condition of the Indian workforce overseen by the mulatto sons of Affonso Ribeiro.

Inácio makes a circuit of the captaincy scandalized by the immorality he finds among the vice-ridden inhabitants, including lascivious priests of Olinda who keep concubines and parade their progeny before him. Duarte Coelho Pereira and his saintly wife Dona Brites are exceptions, but the donatário is old and infirm and unable to govern effectively.

A hemorrhagic epidemic rages at the malocas of Affonso Ribeiro. Inácio confesses the dying degredado. Ribeiro begs the priest to take Salpina, Aruanã’s daughter, back to the Tupiniquin, together with Unauá and Guaraci, the children of Jandaia. In his delirium, Ribeiro reveals that Jandaia is the mother of Nicolau’s bastards.

Inácio confronts his uncle who warns him to see the reality of Santa Cruz, a land of pagans who will raise their bloodstained hands to mock him. Helena asks Inácio not to judge her husband, who has given fifteen years of his life to the conquest of a harsh wilderness. She has shared these years and she understands and forgives Nicolau.

In January 1552, three years after Governor de Sousa’s arrival, Bahia de Todos os Santos – Salvador – is a secure, thriving base. A year passes before Inácio can leave for Porto Seguro. The boy Guaraci takes off on his own, impatient to be with his mother’s people. When Nóbrega finally gives permission for Inácio to go to the Tupiniquin with Salpina and Unauá, they arrive at Aruanã’s malocas as the clan prepares to devour an enemy. Inácio intervenes, carrying off the corpse for burial. Infuriated and perplexed, the Tupiniquin nevertheless allow the priest to begin his mission.

At Porto Seguro, Inácio finds Guaraci a slave of Domingos da Silva and his son, Marcos, who came upon the boy lost and starving on his journey from the Bahia. Inácio forces the da Silvas to release their captive.

Inácio gently rejects Unauá’s advances, a temptation on the eve of going to perform the Jesuit Spiritual Exercises at a place deep in the primeval forest. He returns to find the malocas destroyed by slavers led by Marcos da Silva. He encounters a band of survivors led by the Aruanã, who spares his life. Crushed by the failure of his mission, Inácio returns to the Bahia.

Seven years later, Padre Inácio welcomes Governor Mem de Sá to a great aldeia, the mission village of St. Peter and St. Paul, which has eight-hundred converts of all ages. This triumph is the vision of Nóbrega and José de Anchieta, who see the aldeias as safe havens for the natives. Among the children baptized this day with the governor as his godfather is “Peter,” a survivor of a raid against a Tupinambá clan.

Inácio accompanies Mem de Sá’s army, when a Tupiniquin uprising threatens Porto Seguro and Ilheus. Inácio’s cousin, Tomás Cavalcanti, leads a Pernambucan detachment that joins in the subjugation of the coastal clans, no more poignant than in the slaughter of 1,200 natives on a beach at Ilheus. A 22-day march by Tomás’s column leads to a stockade, where the legendary warrior-chief Aruanã makes a final stand.

The aldeia of St. Peter and St. Paul is swept by a pestilence carried across the Atlantic. The epidemic carries off two-thirds of the mission inhabitants before spreading to the malocas of natives not yet contacted by the Portuguese.

Paulo – Mem de Sá’s godchild, Peter – leads twelve converts into the interior of Bahia, calling himself “Santo Antônio,” and his wife, “Mother of God.” Paulo seeks a promised land where the Tupinambá nation can be reborn.

Twenty years on, Padre Inácio perseveres with two hundred souls in the crumbling aldeia. Word comes of a backlands clan, who want to join the mission of St. Peter and St. Paul. His faith unquenchable, Inácio goes to meet them in the thorn-studded caatinga, “the white forest.” His final moments bring a glorious vision of Our Lady and her favored Saint, in reality Santo Antônio and his wife, who inhabit this stony earth with their disciples.

In August 1628, fourteen-year-old Amador Flôres da Silva and his friend, Ishmael Pinheiro, run away from São Paulo de Piratininga to join the bandeira of Captain-Major Antônio Raposo Tavares, who is leading three thousand men south to the Spanish colony of Paraguay. Amador is the grandson of Marcos da Silva and Unauá, who was captured in the raid on Aruanã’s malocas. Seduced by da Silva, Unauá came to bear his children and to be a devoted wife to the man who brutalized her people.

The bandeirantes, “flag bearers,” are pathfinders, prospectors, militiamen and slavers, as on this expedition directed against the Jesuit missions of Paraguay. Amador is the youngest of sixteen surviving sons and daughters of Bernardo da Silva, a seventy-five-year old mameluco (offspring of Indian and white,) who is one of Raposo Tavares’s trusted lieutenants. Tenente Bernardo has been slave-raiding in Paraguay since long before Amador was born, the incursions facilitated by the fact that Brazil is now a Spanish possession. The crown of Portugal passed to Phillip II of Spain in 1581, after the death of King Sebastião in battle against the Moors at Alcaer-Quibir caused the extinction of the house of Aviz.

Tenente Bernardo feigns anger at Amador’s failure to stay with the cows and pigs at their São Paulo settlement, but privately welcomes this “last-born pup” to his side. Ishmael Pinheiro, the son of an armador, who finances the bandeiras, is sent home by his father, with the advice that he learns to profit by war, not to fight. Amador teams up with two boys whose fathers are attached to Bernardo’s militia: the mameluco Valentim Ramalho, from a great clan related to the castaway João Ramalho, who settled Piratininga plain before the founding of São Paulo; and Abeguar, son of a Tupiniquin slave.

Bernardo leads a reconnaissance of the reduction of San Antonio. His party is ambushed and the tenente wounded. Raposo Tavares visits San Antonio to seek redress. Padre Pedro Mola defends the Guarani, as the Jesuits call the Indians, seen as protecting their fields against the marauders. The bandeirantes have no justification to attack the mission – not until three months later, when spies report that Mola has given sanctuary to runaways from São Paulo.

Tenente Bernardo lies grievously ill and near-blind from his wounds, but insists that Amador guide him to battle. The defenders of San Antonio possess twenty muskets against five times that number in the army of Raposo Tavares. The mission falls, but victory is bitter-sweet for Amador. Bernardo da Silva breathes his last on the great plaza at San Antonio.

Sixty-eight hundred captives are rounded up for the slave market at São Paulo, hundreds perishing on the forty-day march to Piratininga.

Over the next 10 years, Amador and his fellow Paulistas attack the missions carrying off 60,000 natives, until the Jesuits and their Guarani converts finally fight back. At Madrid, where the Company of Jesus enjoys royal favor, the priests seek the arrest of leaders of the bandeiras and their transportation to Lisbon in chains.

Raposo Tavares accepts his one chance for clemency. He raises a company of 150 Paulistas to fight the Dutch occupiers of Pernambuco. With Portugal under Spanish control, Lisbon and its possessions have become embroiled in Philip IV’s exhausting conflict with England, France and Holland. The Dutch invaded Brazil, landing in Pernambuco in the same year Amador was on his first bandeira with Raposo Tavares, and expanded their control from the border of Bahia to Maranhão on the Rio das Amazonas.

Amador has never married, but is the father of two daughters and a son, with Carijó and Tupiniquin concubines. He worships his mother, Rosa Flôres, only one discordant note marring their relationship: Rosa’s support for Maria Ramalho, Valentim’s sister, an inhumanly ugly creature who has made it her life’s challenge to drag Amador to the altar. Maria has persevered in her quest for a decade, ever since wrestling Amador to the ground to become his first lover. There have been many couplings since, but always Amador escapes marriage by marching off with a bandeira.

Amador joins the expedition to Pernambuco. When he bids farewell to his mother at the da Silva lands thirty miles west of São Paulo, Maria Ramalho is there. ”She haunts me – a shadow forever hovering in the background,” Amador tells Ishmael Pinheiro. Ishmael reminds Amador that he’ll be marching down the Serra do Mar with Raposo Tavares and will be saved. “Will I?” Amador asks, glancing at the motionless figure on a nearby bench, her head turned toward him.

In January 1640, an eighty-six vessel armada under Conde de Torre, Dom Fernão Mascarenhas, fails to outgun and outmaneuver a Dutch squadron off Pernambuco. The Paulista contingent is dumped ashore before the fleet scatters. They join an insurgency harassing the Dutch and their Tapuya allies. Amador is with a patrol caught in the valley of Santo Tomás by Jan Vlok, a brutal Hollander, whose men wipe out the mamelucos, all save Amador who is wounded and left for dead.

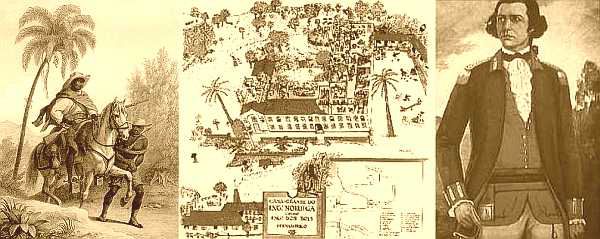

Amador awakes in a casa grande, the big house on the property of Fernão Cavalcanti, whose family has occupied Santo Tomás for more than a century. After five years of futile attempts to expel the Hollanders, Cavalcanti and other planters accept the overtures of Governor Johan Maurits, count of Nassau-Siegen, a liberal and humanist, with a genuine love for Brazil. Cavalcanti serves with a planters’ council organized by Maurits, who gives colonists loans to rebuild engenhos and buy slaves, and will not interfere with Portuguese religion and customs.

Amador knows that the Pernambucanos revile the mamelucos as “mongrels” and “outlaws,” which only deepens his torment over Joana Cavalcanti, Fernão’s daughter, a free-spirited girl who befriends him. What dreams he has of Senhorita Joana are dashed by the arrival of the Dutch artist, Secundus “Segge” Proot, a pupil of Rembrandt van Rijn, who comes to paint the wonders of the second Eden. “Amador, the Bandeirante,” is a subject for his brush strokes. Joana, too, sits for Segge, who captures her heart, her love for him disastrous to her father. Fernão Cavalcanti enlists Amador to save his daughter from the heretic by taking Segge into the wilderness to paint the Indians at their malocas.

Amador and Segge wander the sertão for four years, a backlands odyssey in the desert-like caatinga, across the high cerrado, and through the depths of the rainforest to the Rio das Amazonas. They join forces with the story-teller Ibira, a Tupinambá from the headwaters of the Tapajós. Ibira’s tales of a tribe of warrior women and a lake of gold fill the pair with dreams of El Dorado and the Amazons. They’re swarmed by vampires in the caatinga and taken prisoner by cannibals, who keep them as “cows” ready for slaughter. Rescue comes from Kaimari, chief of a clan of Paresí, with whom they spend ten months, before accompanying Paresí traders to “Love-Me-River,” the Madeira-Mamore, which they ascend towards its confluence with the Amazon.

“Dear God, what a stream! A river sea!” Segge exclaims when they reach the Amazon in July 1644. Segge’s rejoicing turns to a vision of hell, when they encounter an army of slavers from Belém do Pará rounding up the inhabitants of a Tapajós town. Bento Maciel Parente tells them that Johan Maurits was recalled to Holland in May 1644 and most of the Dutch garrison withdrawn. -- A ten-year truce between the Dutch and the Portuguese was ratified in 1641, following restoration of the Bragança throne.

Amador and Segge part ways at the Rio Tapajós. Amador accepts Bento Maciel’s savage treatment of the Tapajós. Segge daringly liberates Tabaliba, the Tapajós chief, who takes him to the one ally of the Indians: Abel O’Brien from County Clare in Ireland. O’Brien is a survivor of a settlement by Roger North, an officer of Walter Raleigh. Bento Parente Maciel’s father put the English and Irish to the sword, including Abel’s love, Rebecca Goodheart.

Able O’Brien and Segge Proot lead a force such as has never been seen before on the Rio das Amazonas to attack Maciel Parente at Death Bird Island sixty miles downriver from the Tapajós town. The slavers’ flagship, Desterro, mounts eight brass cannon and four swivel guns; around the vessel ride eighty canoes bearing slavers and six hundred Tupinambá auxiliaries. The flotilla is attacked by one hundred and fifty war canoes, Abel and Segge at their head, with fire buckets and grenades. Desterro’s nine-pounders fire with a roar and a flash that ignite the explosives in Segge’s canoe killing him instantly. Bento Maciel clears the channel and lands Tupinambá on shore with orders to spare none. Where they fail, the piranhas succeed. Abel O’Brien is caught and beheaded on Death Bird Island.

In June 1645, Amador reaches Engenho Santo Tomás, where a musket-wielding Joana Cavalcanti greets him. Fernão Cavalcanti is in hiding with Pernambucan insurgents, following the betrayal of a planned uprising against the Dutch. Captain Jan Vlok, who massacred Amador’s comrades, commands the local district. And, biggest surprise to Amador, the lovely Joana is married to Jorge Cavalcanti, Fernão’s elder brother, a pompous grandee who spent a decade at the Madrid court before returning to claim his portion of the engenho.

Amador joins Fernão Cavalcanti serving with insurgent leader João Fernandes Viera. They are sent on a secret mission to Palmares, a vast quilombo or stronghold of runaway slaves, whose support the patriots seek against the Dutch.

Nhungaza, captain of the royal regiment at Palmares, escorts the Portuguese to Shoko, capital of the kingdom of “Ganga Zumba.” In fifteen years, Ganga Zumba has attracted fourteen thousand slaves to the foothills of the Serra do Barriga, where he follows the traditions of his people in Africa. Dutch squadrons and planters’ militia have failed to recapture a single slave. Ganga Zumba refuses to send his warriors to battle. Seven years is how long a peça (slave) can expect to live in Brazil, Ganga Zumba tells Cavalcanti. “We have lived fifteen years in these hills – two lives for a peça.” It will be madness to march back to lands where long ago they would have been dead.

At Monte das Tabocas on August 3, 1645, Viera’s troops repulse a Dutch battalion under Colonel Hendrik Haus, which includes the bloodthirsty Jan Vlok. Vlok seeks revenge by striking at the rebels’ plantations and taking their womenfolk hostage. His first target is Engenho Santo Tomás. Fernão’s wife, Domitila, and Joana are carried to Haus’s main camp at the plantation of the widow Dona Ana Paes. Fernão and Amador are in the vanguard of an assault on the Hollanders, which sees the surrender of Haus and the killing of Vlok by Amador who refuses quarter to the heretic.

In November 1645, Amador climbs the crags of the Serra do Mar to São Paulo de Piratininga. Reunited with his family, his greatest joy is finding his mother Rosa Flôres in good health. Maria Ramalho, too, as hideous as Amador remembered her, comes to him riding upon a grey gelding, a huge smile on her round, fleshy face. “Amador Flôres, the Lord sent you back to me!”

Twenty-seven years later, Amador plans a great expedition underwritten by the armador Ishmael Pinheiro. Nine times since his return from Pernambuco, Amador left São Paulo to pursue his march of glory. Three times his bandeiras went in search of emeralds, gold and silver. Ishmael reads a letter from Dom Pedro, prince regent of Portugal to “his wise, far-seeing and discreet subject Senhor Amador Flôres da Silva, conqueror of the sertão” asking that Amador go to discover the treasure of Marcos de Azeredo. Azeredo claimed to have found a mountain of emeralds, but died before revealing the location. – For a prince of Portugal to offer Amador royal honors is the ultimate triumph for a mameluco.

Maria Ramalho is as worthy a wife as Amador’s mother predicted she would be. They have four children: three girls and Olímpio, a muleteer, as stubborn as the packs of beasts he operates between Santos and São Paulo. Maria Ramalho also raises Amador’s eight bastard son and daughters. Trajano, from a Tupiniquin woman, is Amador’s favorite, marching with him on his bandeiras. When they’re away, Maria Ramalho controls their house and lands, everything from managing the slaves to the harvest. She is renowned for her quince preserve, which earns her a handsome profit, most of which goes to financing Amador’s expeditions.

In 1674, Amador leads seventy-six Paulistas and three hundred and eighty natives over the Mantiqueira Mountains to the highlands of Brazil and a range known as Espinhaço, the Spine. Olímpio accompanies his father and Trajano, but when he wants to join the search for Azeredo’s mine, Amador orders him to stay at their headquarters at Sumiduoro.

Four years later, one third of the original bandeira is dead or missing. There have been finds of green stones, every sample rejected as worthless by Procópio Almeida, the expedition’s goldsmith. In the sixth year, Trajano da Silva plots to end Amador’s obsession, but is betrayed. Amador summarily condemns his favorite son and sees him hanged at Sumiduoro.

Twenty months later, Amador discovers emeralds and finally heads back to São Paulo, only to die en route in his sixty-seventh year. Procópio Almeida empties the pouch of stones the old bandeirante carried at his side, not emeralds but flawed tourmalines. The goldsmith saw the lie as the only way to end the madness.

In 1692, Maria Ramalho, almost eighty, and Olímpio visit Ishmael Pinheiro. Maria and her son bring a cask filled with gold to settle Amador’s huge debt to the armador. Over the years, Olímpio and Procópio returned to the highlands on shorter expeditions: Two days’ journey north of the old camp, they found a river of gold, the beginning of the great mines of Brazil. “Your father’s dream, Olímpio,” Maria says. ”What did it matter that Amador hunted emeralds? He led the way!”

{SPOILER ALERT -- This is a synopsis of a novel that runs to 340,000 words. Nonetheless, the PLOT SUMMARY contains incidents and scenes that reveal key elements of the story.]

Paulo Benevides Cavalcanti is the first of his family to be sent from Pernambuco to study at Coimbra in Portugal. In October 1755, Paulo and Luis Fialho Soares, a fellow student who hails from Minas Gerais, are waiting to embark on the Estrêla do Mar, sailing for Brazil in mid-November. They spend a weekend at Sintra with a fellow graduate, Marcelino Augusto Fonseca, whose father Dom António Fonseca is a wealthy merchant.

The young men stand in awe of a guest in the Fonseca salon: Sebastião José Carvalho e Melo, Minister of Foreign Affairs and War. No man in Portugal except King José is more powerful than Carvalho e Melo. The minister expresses contempt for the ruling clique of nobles and ecclesiastics who he blames for impoverishing the royal coffers. The gold strikes in Brazil in the 1690s have been followed by finds of vast diamond fields in a “Forbidden District,” 130 miles in circumference, reserved for the Crown. Carvalho e Melo complains that half the gold and diamonds from Minas Gerais goes to London to pay for Portugal’s debts. His strongest criticism is leveled against the Jesuits at the Portuguese court and in South America. It is common knowledge that the Minister and the Company of Jesus are on a collision course.

At 9.45 A.M. on November 1, 1755, All Saints Day, Paulo Cavalcanti is at the window of a four-story house on a precipitous street northeast of Rossio square in the heart of Lisbon. Luis Fialho is attending mass at the Basilica de Santa Maria, below Castelo do São Jorge. A tremor shakes the house, and ten seconds later, a devastating shock. Terremoto! The word crashes through Paulo’s senses. Earthquake!

In fifteen minutes, one third of Lisbon is reduced to rubble. An hour later, Paulo is on the Terreiro do Paço, the palace square, when a monstrous tidal wave races into the mouth of the Tagus. It roars inland, smashing through anchorages, demolishing buildings and sweeping away the Cais de Pedra, a marble-faced quay, with hundreds who sought safety here. Paulo survives the cataclysm and reaches Rossio. Carvalo e Melo is surveying the damage. A fidalgo suggests that they move the capital to Coimbra. The minister dismisses the idea, even as the skyline is lit with fires. “I will rebuild Lisbon,” he vows.

Luis Fialho Soares is wrongfully arrested for looting and thrown into the Tower of Belêm, where Paulo finds him after a month-long search. Dom António Fonseca gets Carvalho e Melo’s help in securing the young Brazilian’s release.

In May 1756, Bartolomeu Rodrigues Cavalcanti hosts a five-day festa to celebrate Paulo’s safe return to Engenho Santo Tomás, where a thirty-room casa grande with private chapel dominates the high ground occupied by six generations of Cavalcantis. Bartolomeu Rodrigues’s control of the vast estate with one hundred and fifty one slaves is firm but benign. The 68-year-old patriarch and Dona Catarina have five daughters and three sons. Geraldo at nineteen is the younger of Paulo’s brothers – a pleasant, lazy youth with a grand disinterest in most things; Graciliano is twenty-one, restless and impatient, and possessing a violent temper.

Estevão Ribeiro Adorno, descended from the great clan of Affonso Ribeiro, is head vaqueiro at Fazenda da Jurema, the Cavalcanti ranch in the interior of Pernambuco. In July 1756, Paulo and Padre Eugênio Viana, Santo Tomás’s priest, make the ten-day journey to Jurema, for the annual count of the herd of 5,500 beasts roaming 130 square miles of scrub. To Viana, Ribeiro Adorno and his people represent a never-ending exodus of the weak, the dispossessed, and the landless from the fertile Canaan of the coastal valleys to the backlands. By the time civilization advances here, will it come up with a brutal and impetuous race lost in the caatinga, Viana wonders presciently.

Paulo marries Luciana Costa Santos, the daughter of an independent cane grower in a valley controlled by the Cavalcantis. Five months after his brother’s wedding, Graciliano takes as lover Januária Ribeiro Adorno, who visits the engenho with her father on a cattle drive to the coast. Graciliano runs off with the girl to the Cavalcanti’s town house at Olinda. Bartolomeu Rodrigues leads six men to fetch Graciliano, who is carried back to Santo Tomás after a thrashing. Three weeks later, Graciliano leaves for good, riding off to the wilderness of Jurema and wild Januária.

At Lisbon in September 1759, King José I, issues a royal edict banning all Jesuits from his domains, a triumph for minister Carvalho e Melo, soon to be Marquis de Pombal. Two priests at the aldeia of Rosário near Santo Tomás join the exodus of 629 Jesuits from Portuguese America. Elias Souza Vanderley is appointed director of the settlement, with minute regulations to reform the natives and free blacks and integrate them into Portuguese society. One of Vanderley’s first tasks is to erect a pelourinho, a sixteen-foot pillory, symbol of the king’s authority.

Pedro Prêto, “Black Peter,” is a great grandson of Nhungaza, captain of the royal regiment of Ganga Zumba. A former slave, Pedro flourished under the Jesuits, becoming a skilled carpenter and serving with Rosário’s council of elders. Vanderley begins his regime by ordering Black Peter to remodel the priests’ quarters, where the director is soon ensconced with a supply of cachaça and concubines.

In July 1766, Director Vanderley, grown huge and bloated, witnesses the punishment of a thief at the pelourinho: Black Peter is condemned to one hundred lashes. Pedro was sent to fell and trim a stand of brazilwood trees found by Indians on lands without an owner. Five loads were delivered to Rosário when a peddler came by with an empty wagon. He offered payment in silver for seven logs. When Vanderley learned of the sale, he threw Black Peter into jail.

Three days after the flogging, as Pedro lies lacerated and exhausted, Vanderley and his overseer, Little George, rape Jovita and Vera, the daughters of Black Peter. When their father learns of the crime, he takes a double-bladed ax and kills the director in his bed before fleeing Rosário with two accomplices. Inspired by his ancestor who stood with Ganga Zumba, Black Peter begins a slave insurrection that spreads through the valleys of Pernambuco.

Paulo Cavalcanti rides with a militia hunting for Pedro and his band. A surprise attack at a creek beyond Rosário leaves the company without mounts and supplies. Paulo and two mixed-breeds go on foot to an engenho to seek horses. The front door is flung open by Black Peter, whose men occupy the plantation. Paulo is brutally tortured and murdered, Pedro himself dealing the death blow.

Graciliano returns to Santo Tomás summoned by his grieving father. Bartolomeu Rodrigues presses his head against the dusty leather of Graciliano’s long coat. “Meu filho! Meu filho! My son, it is over,” the senhor says, asking forgiveness for his pride and vanity. Graciliano vows to avenge his brother. “Paulo lies in the chapel,” Bartolomeu Rodrigues says. “Go softly, Graciliano. Make your vow to him.”

Graciliano leads a rustic cavalry of forty-two vaqueiros and engenho workers to the Serra do Barriga and the ruins of Palmares. Black Peter and his band are dug in at the former royal enclosure of Shoko. The vaqueiros storm a fortified embankment meeting a hail of bullets, but in ten minutes the fight is over. Pedro escapes to a rocky summit above the quilombo. Graciliano follows the fugitive to the Place of Stones and kills Black Peter in Ganga Zumba’s sanctuary.

Benedito Bueno da Silva has a reputation for courage equal to that of his ancestor Amador Flóres da Silva. He is the grandson of Olímpio Ramalho, the muleteer who struck gold in Minas Gerais. Benedito Bueno continued the mighty pathfinding adventures of men like Amador by leading river convoys to the goldfields of Cuiabá in Mato Grosso, a circuitous voyage of 3,500 miles. Since 1739, when he was thirteen, Benedito Bueno has made thirty journeys with the “monsoons,” so called for their seasonal departures from Porto Feliz, a canoe landing eighty miles northwest of São Paulo on the Rio Tieté.

At Itatinga on a horseshoe bend of the Tieté forty miles beyond Porto Feliz, Benedito Bueno got a land grant of nine square miles where he moved his wife and sons from the original da Silva property. Like his forbears, Benedito Bueno wanted to be in the sertão beyond effective reach of authority, where he could wield absolute power over the fifty-six souls at Itatinga and over the men of his pirogues. He enjoyed this independence for twenty years. With an increasing drift of colonists from São Paulo, a settlement grew up at Tiberica, a cattle halt south of Itatinga, granted town status in 1766. Silvestre da Silva, Benedito Bueno’s first-born son, welcomes these developments, accepting that the age of the bandeirantes is coming to a close and settling down to develop Itatinga.

On a morning in April 1788, Silvestre and two visitors witness the agony of Benedito Bueno laid low by a gnawing toothache. André Vaz da Silva, descended from Trajano who was executed by Amador, is a merchant at Vila Rica de Ouro Prêto, the capital of Minas Gerais. The second visitor is André’s friend, Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, alferes, a second lieutenant in the Sixth Company of Dragoons of Minas Gerais. The dragoon is a man of many talents, one that earns him his nickname Tiradentes, “Tooth-Puller.” Silva Xavier travels with his dental equipment and deftly does his work, extracting the monsoon captain’s decayed molar.

Alferes Silva Xavier and André Vaz share the Mineiros’ discontent at the plunder of Brazil by the royal treasury at Lisbon. The Crown’s demand of a thousand arrobas of gold a year – five hundred thousand ounces – was paid for a decade until the gold supply diminished. Now in arrears, the inhabitants of Minas Gerais are threatened with the derrama, a tax on every free man and slave, to make up the shortfall. Appeals for local enterprises such as a foundry are rejected to preserve Lisbon’s monopolies and British dominance of the Brazil trade.

At Itatinga, Silva Xavier expresses disgust at despotic government and suggests an alternative by reading to his hosts from the Declaration of Rights by the people of Virginia. Silvestre da Silva calls this is a prescription for revolution. These truths, Tiradentes responds, are the voice of reason against turmoil. They were given by men claiming their natural right to reject tyranny.

At Vila Rica de Ouro Prêto, a city of 80,000, Luis Fialho Soares, who survived the Lisbon earthquake with Paulo Cavalcanti, belongs to a cross-section of influential Mineiros – magnates, lawyers, priests, soldiers and farmers, poets and intellectuals, who meet regularly, their discussions driven by the winds of freedom blowing between the crags of Minas Gerais. Luis Fialho’s son, Fernandes Soares, returns from his medical studies in France, where he knew José de Maia, a fellow Brazilian dedicated to liberating their homeland. Fernandes and Maia met Thomas Jefferson at Nimes, when the Minister was taking the waters at Aix after a fall in which he cracked his wrist. Jefferson has no authority to promise direct aid, but is sympathetic to the idea of a free and independent Brazil.

Silva Xavier emerges as leader of the disparate group fanning an insurrection against Her Majesty Maria I’s government. Within three months, the Tooth-Puller’s war of words brings Minas Gerais to the brink of revolution. The imposition of the derrama is widely anticipated in February 1789, a royal extortion seen as ideally suited for the launching of a rebellion. A war of independence is expected to last three years, the new American republic to be launched under the banner of Libertas, quae sera tamen, “Liberty, even though late!”

André Vaz and Fernandes Soares transport a wagonload of gunpowder over the Mantiqueira Mountains, challenged by a band of highwaymen led by Dançerino da Corda. They outwit Rope Dancer and deliver the explosives to a fazenda in readiness for the uprising.

February passes without imposition of the new tax by the governor of Minas Gerais, visconde de Barbacena. Silva Xavier and the poet Alvarenga Peixoto, a wealthy fazendeiro and militia colonel, want to march immediately, but others hesitate. Silvério dos Reis, a tax farmer who owes the royal treasury the equivalent of a ton of gold goes to strike his own bargain with visconde de Barbacena: a full pardon for his debts in exchange for exposing the conspiracy against the Crown.

Alferes Silva Xavier and twenty-eight others involved in the “Inconfidência Mineira” are arrested and transported to the dungeons of Rio de Janeiro, where they are held incommunicado for thirty months. In 1792, Silva Xavier and ten men are sentenced to death. André Vaz and Fernandes Soares are banished to Africa for ten years. The royal tribunal spares the lives of all but one of the condemned: Tiradentes. Silva Xavier is led through the streets of Rio de Janeiro to be hanged at the field of Santo Domingo. ‘I have kept my word, I die for liberty,” is the Tooth-Puller’s last glorious confession.