HOME BRAZIL BRAZIL-ARCHIVES RIDING THE RAILS REVIEWS BIOGRAPHY

BRAZIL — The Illustrated Guide to the Novel

Part One

Slave Market at Rio de Janeiro

A free online guide with a wealth of photos and illustrations giving a unique insight into the novel and its creativity.

I searched for the story of Brazil for five years, a literary pathfinder in quest of the epic of the Brazilian people. In this guide, I share my private journal kept on a mighty trek of twenty thousand kilometers across the length and breadth of a vast country.

Discover the magic that goes into the making of a monumental novel with a first draft of three-quarters of million words written in the old-fashioned way, by hand! A quest driven by a passion for writing and storytelling.

Links to the Illustrated Guide to Brazil can be found at the end of each Book Section enhancing the reader's enjoyment of a spellbinding saga "with the look and feel of an enchanted virgin forest, a totally new and original world for the reader-explorer to discover."

Errol Lincoln Uys

Boston, 2014

IMAGE CREDITS APPEAR AT END OF GUIDE

Captions from the text of BRAZIL ©2014 Errol Lincoln Uys

![Tupinamba Village, Brazil 16th Century [1]](../images/TupinamapalisadedvillageStaden1557.jpg)

The village below was the largest his people had built, and had been enclosed by a double stockade of heavy posts lashed together with vines — two great circles that protected the five dwellings arranged around a central clearing. These malocas were no rude forest huts but the grand lodges of the five great families of the clan.

![Brazilian Indians, 16th Century [2]](../images/Brazil16thcenturyTupinamba.jpg) Now

the men in the clearing began to dance around the pagé, stamping their

feet in such a way that the seedpods tied around their calves shook in unison.

from many mouths came the cries:"Now speak, O Voice of the Spirits."

Now

the men in the clearing began to dance around the pagé, stamping their

feet in such a way that the seedpods tied around their calves shook in unison.

from many mouths came the cries:"Now speak, O Voice of the Spirits."

![Nambikwara by Claude Levi-Strauss [3]](../images/NambikwaraSleepCLeviStrauss1994-full.jpg) Sex,

above all, was the Nambikwara's delight. Making love was good, they said —

and they did so with gusto whenever the opportunity arose.

Sex,

above all, was the Nambikwara's delight. Making love was good, they said —

and they did so with gusto whenever the opportunity arose.

![Madeira-Mamore rapids near Porto Velho [4]](../images/MadeiraMamore300.jpg) Their

passage was relatively easy except in those places where the river roared over

a cataract and their small craft was shot through a narrow channel between the

rocks.

Their

passage was relatively easy except in those places where the river roared over

a cataract and their small craft was shot through a narrow channel between the

rocks.

![Rain forest [5]](../images/Amazon.jpg) They

passed through two new moons, two men and a boy, voyaging into the heart

of a great continent, as much in harmony with this wilderness as the animals

that sought the riverbanks, leaving scant trace of their presence as they moved

from one bend of the stream to the next.

They

passed through two new moons, two men and a boy, voyaging into the heart

of a great continent, as much in harmony with this wilderness as the animals

that sought the riverbanks, leaving scant trace of their presence as they moved

from one bend of the stream to the next.

![Amazon River island, tree roots [6]](../images/Manausforest1.jpg) But

their innate suspicion of the evil that stalked humans in such mysterious places

often made them fearful.

But

their innate suspicion of the evil that stalked humans in such mysterious places

often made them fearful.

![Two jaguars, BBC [7]](../images/jaguarsbbc.jpg) The

jaguars rested between the canes, their cold yellow eyes unblinking as they

peered into the darkness.

The

jaguars rested between the canes, their cold yellow eyes unblinking as they

peered into the darkness.

![Quipu yupana, chronicle, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala [8]](../images/khipu.jpg) Among

the objects in Tocoyricoc's cave was something even more magical to Aruanã

— "the lines that remembered." They appeared to be a bunch of

bowstrings of different colors and lengths knotted together untidily. Tocoyricoc

used a word from his own language to describe them: quipu.

Among

the objects in Tocoyricoc's cave was something even more magical to Aruanã

— "the lines that remembered." They appeared to be a bunch of

bowstrings of different colors and lengths knotted together untidily. Tocoyricoc

used a word from his own language to describe them: quipu.

![Quipu, Meyer's Konversationslexikon. 1888 [9]](../images/Quipu.jpg) When

Aruanã first saw the old man consult it, he'd picked out a red cord.

"First knot," he said,"is battle of Black Valley, where a young

Tocoyricoc fought. Two and one knots is the age he had, this is his place among

the warriors, these, the number of enemy killed."

When

Aruanã first saw the old man consult it, he'd picked out a red cord.

"First knot," he said,"is battle of Black Valley, where a young

Tocoyricoc fought. Two and one knots is the age he had, this is his place among

the warriors, these, the number of enemy killed."

"What magic is this?"

"It is a away or remembering," he said. "To show what is past."

![Sunrise over Machu Picchu, Peru, Allard Schmidt [10]](../images/MachuPicchuoftheIncas.jpg) "This

was the land where Master — one you would call Great Chief — arose.

Son of the Sun. He came to change our world when I was your age .Before He-Who-Trans-forms,

we were a miserable people living as those who see nothing but the forest."

His voice shook with emption as he told Aruanã about this great sky-being.

He showed the young man his own golden earplugs — "tears of the sun"

— and

said that they were pitiful things compared with what adorned the Master.

"This

was the land where Master — one you would call Great Chief — arose.

Son of the Sun. He came to change our world when I was your age .Before He-Who-Trans-forms,

we were a miserable people living as those who see nothing but the forest."

His voice shook with emption as he told Aruanã about this great sky-being.

He showed the young man his own golden earplugs — "tears of the sun"

— and

said that they were pitiful things compared with what adorned the Master.

![Cannibalism, Brazil, 16th Century [11]](../images/Tupinamaboucan.jpg) Yware-pemme

struck again and again, and quickly there were three groups of women at work

in the clearing.

Yware-pemme

struck again and again, and quickly there were three groups of women at work

in the clearing.

![Cannibals, 16th Century, Brazil, dismemberment [12]](../images/StadenColor.jpg) The

enemy were being dismembered with bamboo knives and stone ax. The trunks were

split, the intestines removed and set aside: these would go with other parts

of the viscera into a great broth, which all would sip, taking the strength

of the enemy.

The

enemy were being dismembered with bamboo knives and stone ax. The trunks were

split, the intestines removed and set aside: these would go with other parts

of the viscera into a great broth, which all would sip, taking the strength

of the enemy.

![Cannibals grill enemy on a boucan, Brazil, 16th Century [13]](../images/Stadencolor2.jpg) The

butchers caroused and sometimes squabbled over the joints; the men danced in

the clearing and sang with joy at having seen the suffering of the Cariri. So

it would go, they warned, with any who dared gnaw the bones of Tupiniquin.

The

butchers caroused and sometimes squabbled over the joints; the men danced in

the clearing and sang with joy at having seen the suffering of the Cariri. So

it would go, they warned, with any who dared gnaw the bones of Tupiniquin.

![Brazilian Indian chief adorned for a festival, Debret [14]](../images/BrazilianNatives.jpg) Juriti

brought his son; he heard the strong cry and saw the robust little body and

was enormously relieved that his efforts thusfar had succeeded. Encouraged,

he faced his confinement.

Juriti

brought his son; he heard the strong cry and saw the robust little body and

was enormously relieved that his efforts thusfar had succeeded. Encouraged,

he faced his confinement.

![Porto Seguro [15]](../images/PortoSeguro.jpg) On

the beach where he walked for the shells, Aruanã

On

the beach where he walked for the shells, Aruanã

felt contentment at being alone. One man, alone, at the edge of his world, his bare feet making an impression along great curves of sand.

![Indian canoes, Porto Seguro, Brazil [16]](../images/PortoSeguro2.jpg) And

then, at the height of his happiness, came a premonition...

And

then, at the height of his happiness, came a premonition...

Tiny puffs of cloud had fallen to the end of the earth. Four...five...six...were bunched together just above the horizon. Otherwise the sky was perfectly clear.

![Pedro Alvares Cabral, landing, Brazil 1500 [17]](../images/PortoSeguroLanding.jpg) They

were there, darkening images now, these canoes that had come from the end of

the earth.

They

were there, darkening images now, these canoes that had come from the end of

the earth.

![Brazil Map, 1519, Lope Homem [1]](../images/Brazilmap1519PortugueseLopoHomem.jpg) "Sixty-four

days out of Lisbon," the fidalgo said, "forty days west of Cabo Verde,

and still no Terra de Santa Cruz..."

"Sixty-four

days out of Lisbon," the fidalgo said, "forty days west of Cabo Verde,

and still no Terra de Santa Cruz..."

Cavalcanti did not reply immediately. He was thinking of Gomes de Pina's use of the old name — Land of the Holy Cross — given to the territory by Pedro Álvares Cabral when he discovered it for Portugal in 1500. On the Lisbon waterfront, to men who knew better, it was Terra do Papagaio (Land of Parrots) or Terra do Brasil, named for the brazilwood taken from its wild shores.

![Caravel [2]](../images/caravelgrand.jpg) What

distinguished Sao Gabriel from those rakish caravels was her size —

120 tons against fifty or so; her broad, square sails spreading above a wide

beam; her towering castles fore and aft.

What

distinguished Sao Gabriel from those rakish caravels was her size —

120 tons against fifty or so; her broad, square sails spreading above a wide

beam; her towering castles fore and aft.

![Afonso de Albuquerque (1462-1515) [3]](../images/Afonso_de_Albuquerque.jpg) Afonso

de Albuquerque's name was already a byword for terror among the petty kings

and sultans along the coast of India: O Terrível (The Terrible), they

called him...

Afonso

de Albuquerque's name was already a byword for terror among the petty kings

and sultans along the coast of India: O Terrível (The Terrible), they

called him...

![Ormuz 1572 [4]](../images/ormuz.jpg) Sofala,

Aden, Ormuz, Malacca — all were strategic points on the trade routes across

the Indian Ocean, but none was so commanding as Goa. Let the Infidel hold the

others, Albuquerque said, and the Indies could be conquered from Goa.

Sofala,

Aden, Ormuz, Malacca — all were strategic points on the trade routes across

the Indian Ocean, but none was so commanding as Goa. Let the Infidel hold the

others, Albuquerque said, and the Indies could be conquered from Goa.

![Map of Goa 1595 [5]](../images/GoaMap.jpg) For

eighty-four days the ships held out; on the eighty-fifth day, the monsoon over,

they could finally weigh anchor. But it was not long before Albuquerque was

back, this time in a great armada with 1,700 fighting men. By ten o'clock on

the feast day of St. Catherine, the garrison at Goa had fallen.

For

eighty-four days the ships held out; on the eighty-fifth day, the monsoon over,

they could finally weigh anchor. But it was not long before Albuquerque was

back, this time in a great armada with 1,700 fighting men. By ten o'clock on

the feast day of St. Catherine, the garrison at Goa had fallen.

![Boats in Goa, Jan Hughen Van Linschoten [6]](../images/BoatsinGoa.jpg) For

three days and three nights the fighting had raged in the city. By dawn on the

fourth day, when O Terrível decreed a halt, they had slain six thousand

disbelievers, men, women and children, for Portugal — and for Christ.

For

three days and three nights the fighting had raged in the city. By dawn on the

fourth day, when O Terrível decreed a halt, they had slain six thousand

disbelievers, men, women and children, for Portugal — and for Christ.

![Jeronimos Monastery, Belem, Lisbon [7]](../images/Jeronimos.jpg) Gomes

de Pina had ordered his vessels tarry in the river while he held a holy vigil

in the new church of the Jeronymites, built at nearby Belém in gratitude

to God for the passage to India. He'd assembled his family and hangers-on and

proceeded to prayerful office — in the manner of great navigators like

Vasco da Gama and Pedro

Gomes

de Pina had ordered his vessels tarry in the river while he held a holy vigil

in the new church of the Jeronymites, built at nearby Belém in gratitude

to God for the passage to India. He'd assembled his family and hangers-on and

proceeded to prayerful office — in the manner of great navigators like

Vasco da Gama and Pedro

Álvares Cabral, who had knelt in the humble chapel that had stood on the ground now occupied by the majestic limestone monastery.

![Belem Tower, Lisbon [8]](../images/Torre_de_Belem.jpg) When

his lonely appeal was over, Gomes de Pina had led his entourage to the water's

edge, where a boat awaited to carry him to the ships. They were anchored close

to the Tower of St. Vincent, a great bulwark that rose on a group of rocks in

the Tagus.

When

his lonely appeal was over, Gomes de Pina had led his entourage to the water's

edge, where a boat awaited to carry him to the ships. They were anchored close

to the Tower of St. Vincent, a great bulwark that rose on a group of rocks in

the Tagus.

![Christopher Columbus, posthumous portrait, Florentine painter Ridolfo Ghirlandaio (1483-1561) [9]](../images/Colomb.jpg) Cavalcanti

looked at the caravels in the distance, his eyes searching the vast expanse

of moonlit sea.

Cavalcanti

looked at the caravels in the distance, his eyes searching the vast expanse

of moonlit sea.

Was it a night like this, in the year of Our Lord Jesus Christ 1492, when Cristovão Colombo first saw Ilha San Salvador? O Santa Maria! The scheming Genoese adventure sailing for Castile and Aragon! O Portugal, robbed by Spanish dogs and the traitors who sail in their ships!

![Vasco da Gama landing in India [10]](../images/VascodagamalandsatCalicut.jpg) When

Columbus was on his third voyage in 1498, the Portuguese navigator Vasco da

Gama reached India via the Cape of Good Hope...

When

Columbus was on his third voyage in 1498, the Portuguese navigator Vasco da

Gama reached India via the Cape of Good Hope...

![Pedro Alvares Cabral, discoverer of Brazil [11]](../images/PedroAlvaresCabral2.jpg) Two

years later, Pedro Álvares Cabral, commander of the second Indies fleet,

veered far to the west, making an unexpected landfall ar Terra de Santa Cruz

on April 22, 1500.

Two

years later, Pedro Álvares Cabral, commander of the second Indies fleet,

veered far to the west, making an unexpected landfall ar Terra de Santa Cruz

on April 22, 1500.

![Cross at site of Cabral's landing, Brazil, modern replica [12]](../images/PortoSeguro1.jpg) At

last they stood in toward that wide, beautiful bay. Near the beach they saw

the great cross raised by Cabral.

At

last they stood in toward that wide, beautiful bay. Near the beach they saw

the great cross raised by Cabral.

![Second Mass in Brazil, artist, Vitor Meireles, Museu Nacional de Belas-Artes, RJ [13]](../images/PortoSeguroFirstMass.jpg) Aruanã

was remembering the day Cabral held the first devotions at this cross: As the

pagés of the Long Hairs had gone about their sacred work, the Tupiniquin

had followed their actions, kneeling when they knelt, standing with their hands

uplifted, and breathing not a word when they were silent.

Aruanã

was remembering the day Cabral held the first devotions at this cross: As the

pagés of the Long Hairs had gone about their sacred work, the Tupiniquin

had followed their actions, kneeling when they knelt, standing with their hands

uplifted, and breathing not a word when they were silent.

![King Joao I of the Kongo, 16th century [14]](../images/JoaoIoftheKongo.jpg) Who

would acknowledge, for instance, that there was a black chief who called himself

Affonso I, son of King João da Silva, (John of the Woods) and Queen Eleanor;

who ruled his lands not with chiefs and elders but with nobles he addressed

as his duques, marquezes, viscondes and baroes?

Who

would acknowledge, for instance, that there was a black chief who called himself

Affonso I, son of King João da Silva, (John of the Woods) and Queen Eleanor;

who ruled his lands not with chiefs and elders but with nobles he addressed

as his duques, marquezes, viscondes and baroes?

![São Salvador, capital of the Kingdom of Kongo, in the late 17th century [15]](../images/Kongocapital.jpg) Cavalcanti's

first impression of Mbanza, palace and place of justice of the ManiKongo, was

one of confusion. He was taken back by the sight of a wall, like those in Portugal,

raised before this city in the heart of Africa.

Cavalcanti's

first impression of Mbanza, palace and place of justice of the ManiKongo, was

one of confusion. He was taken back by the sight of a wall, like those in Portugal,

raised before this city in the heart of Africa.

![King of Kongo giving audience to Portuguese and his subjects [16]](../images/Kongo_audience.jpg) Affonso

I, Lord of the Kongo, sat on a throne inlaid with gold and ivory and draped

with leopard skins. He was dressed in the fashion of a Portuguese noble, with

scarlet tabard, pale silk robe, satin cloak with embroidered coat of arms, and

velvet slippers.

Affonso

I, Lord of the Kongo, sat on a throne inlaid with gold and ivory and draped

with leopard skins. He was dressed in the fashion of a Portuguese noble, with

scarlet tabard, pale silk robe, satin cloak with embroidered coat of arms, and

velvet slippers.

![Dress of the women of Kongo [17]](../images/DressofwomenofKongoBry.jpg)

There were women, too, dressed as Portuguese donas, with veils over their faces and velvet caps and gowns. Their gold and jewels were such as few ladies of Lisbon possessed.

![Hottentot or Khoi-khoi. top [18]](../images/Daniell_Hottentot_000.jpg) "Not

east but south," the slaver said. "They are Khoi-khoi who bring copper

and ostriches to the kingdom. They live near the Cape." — The

Cape of Good Hope, at the tip of Africa.

"Not

east but south," the slaver said. "They are Khoi-khoi who bring copper

and ostriches to the kingdom. They live near the Cape." — The

Cape of Good Hope, at the tip of Africa.

![Slave Traders at the mouth of the Congo River [19]](../images/SlavesandSlaversatmouthofCongo.jpg) Sancho

de Sousa sent his customs officials to brand the captives, marking their breasts

with a red-hot iron. When this was done, Padre Miguel had the slaves assembled

and informed them that they were to be baptized.

Sancho

de Sousa sent his customs officials to brand the captives, marking their breasts

with a red-hot iron. When this was done, Padre Miguel had the slaves assembled

and informed them that they were to be baptized.

"You will taste the salt of our faith," he told them. "Your souls, servants, will be free."

![Sintra Palace, Sintra, Portugal [20]](../images/SintraPalace_000.jpg) In

the domed Sala das Armas of Sintra palace on a day in October 1534, the fidalgo

Dom Duarte Coelho Pereira sat listening to the Keep of Records, Belchior da

Silveira, read part of a petition taken from the royal archives....

In

the domed Sala das Armas of Sintra palace on a day in October 1534, the fidalgo

Dom Duarte Coelho Pereira sat listening to the Keep of Records, Belchior da

Silveira, read part of a petition taken from the royal archives....

![Sintra Palace, Sala das Armas [21]](../images/SaladasArmas.jpg) "I

don't know this Cavalcanti," Dom Duarte repeated, "but it's obvious

he's not fooled by parrots and logs: he sees the one thing that will bring a

profit from Brazil."

"I

don't know this Cavalcanti," Dom Duarte repeated, "but it's obvious

he's not fooled by parrots and logs: he sees the one thing that will bring a

profit from Brazil."

"Which is?""Sugar! Sugar will be the treasure of our New World!"

![Cabo da Roca, Sintra, westernmost point of Europe [22]](../images/Cabo_da_Roca.jpg) Days

passed in which Nicolau said little to his family about Dom Duarte's visit.

He wandered off alone through the woods, to the very edge of the land, where

the blue-gray Atlantic rolled against the rocks.

Days

passed in which Nicolau said little to his family about Dom Duarte's visit.

He wandered off alone through the woods, to the very edge of the land, where

the blue-gray Atlantic rolled against the rocks.

Cabo da Roça, Sintra

westernmost point of Europe

![Iguarassu, Pernambuco, Brazil [23]](../images/igarassupernambuco.jpg) A

start had been made at a settlement also called Santa Cruz, but soon the settlers

had moved inland to this more elevated position, and named it Villa do Cosmos,

for the saint. Shortly, however, they were seduced by the cadences of the native

word Iguarassu (Big River) and had begun to use it for both "stream"

and "village."

A

start had been made at a settlement also called Santa Cruz, but soon the settlers

had moved inland to this more elevated position, and named it Villa do Cosmos,

for the saint. Shortly, however, they were seduced by the cadences of the native

word Iguarassu (Big River) and had begun to use it for both "stream"

and "village."

![Olinda, Pernambuco, Brazil {24]](../images/Olinda.jpg) Dom

Duarte had not been happy with this choice of Iguarassu as his main base. A

few weeks before, he had seen his "Lisbon": on the coast twenty-five

miles to the south, there were seven hills, from any one of which he could look

far inland, and which could be admirably defended seaward.

Dom

Duarte had not been happy with this choice of Iguarassu as his main base. A

few weeks before, he had seen his "Lisbon": on the coast twenty-five

miles to the south, there were seven hills, from any one of which he could look

far inland, and which could be admirably defended seaward.

There was at this time an old romance of chivalry and knighthood with its heroine, Olinda, a name meaning beautiful. Dom Duarte found this a perfect description for those seven hills facing the sea: Olinda

![Saint Francis Xavier receiving the Jesuit Asian mission [1]](../images/StFrancisXavierreceivingtheJesuitAsianmission.gif) In

Lisbon, Inácio never strayed far from Francis Xavier's side. When the

time came for Xavier's departure, Inácio had wept openly. "Follow

Simon Rodrigues," Xavier had consoled him. "Obey his instructions

and the Lord will surely indicate His will for you."

In

Lisbon, Inácio never strayed far from Francis Xavier's side. When the

time came for Xavier's departure, Inácio had wept openly. "Follow

Simon Rodrigues," Xavier had consoled him. "Obey his instructions

and the Lord will surely indicate His will for you."

![Dom Joao III of Portugal [2]](../images/DomJoaoIII.jpg) Dom

João III, entering middle age, was becoming increasingly concerned with

the special duty demanded of a Most Catholic Majesty — the saving of his

subject's souls. He was distressed when the two Jesuits informed him that his

opulent and worldly Lisbon was as wicked and profane a locality as any they

expected to encounter in some heathen land. While they waited for a ship, they

announced, they would devote themselves to purging the capital.

Dom

João III, entering middle age, was becoming increasingly concerned with

the special duty demanded of a Most Catholic Majesty — the saving of his

subject's souls. He was distressed when the two Jesuits informed him that his

opulent and worldly Lisbon was as wicked and profane a locality as any they

expected to encounter in some heathen land. While they waited for a ship, they

announced, they would devote themselves to purging the capital.

![Coimbra University, ancient portal [3]](../images/CoimbraUniversityOldGate.jpg) Perceiving

the young man's grace and devotion, Rodrigues had ordered him to Coimbra University

— which João III had donated to the Jesuits — to commence

the studies he would have followed at Paris. "Arm yourself, Inácio,"

Rodrigues had said,"to win the minds and hearts of others."

Perceiving

the young man's grace and devotion, Rodrigues had ordered him to Coimbra University

— which João III had donated to the Jesuits — to commence

the studies he would have followed at Paris. "Arm yourself, Inácio,"

Rodrigues had said,"to win the minds and hearts of others."

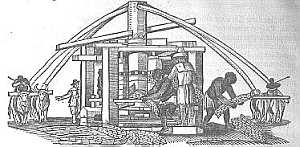

A

sugar press stood beneath a palm-thatched roof at one side of the plaza, oxen

straining against the great arms that turned the rollers into which men fed

the cane stalks.

A

sugar press stood beneath a palm-thatched roof at one side of the plaza, oxen

straining against the great arms that turned the rollers into which men fed

the cane stalks.

![Molasses Cauldron, Pernambuco, 17th Century [5]](../images/sugarcane2.jpg) Near

these workers, other blacks and natives of Santa Cruz labored at the molasses

cauldrons.

Near

these workers, other blacks and natives of Santa Cruz labored at the molasses

cauldrons.

![Sugar plantation, engenho, Pernambuco, Brazil 1640 [6]](../images/engenho.jpg) "Build

the new mill, Nicolau, not for Engenho Santo Tomas alone but for others...They'll

have to bring every stalk they grow to your mill. And you take two out of every

three stalks as compensation...."

"Build

the new mill, Nicolau, not for Engenho Santo Tomas alone but for others...They'll

have to bring every stalk they grow to your mill. And you take two out of every

three stalks as compensation...."

![Governor Tome de Sousa, Brazil [7]](../images/tomedesouza.jpg) Governor

Tomé de Sousa was aware that beyond the Bahia in the forests of the hinterland

were thousands of savage Tupinambá. "So many savages that they would

never lack," the governor reported to Lisbon, "even if we were to

cut them up in slaughter-houses." He did not balk at punishing those who

dared interfere with his plans, and he took such action not for his sake alone

but for the glory that should be promised King João in this land. "The

Pious," as the king was now called, had made it clear that this time he

would tolerate no nonsense from his native subjects.

Governor

Tomé de Sousa was aware that beyond the Bahia in the forests of the hinterland

were thousands of savage Tupinambá. "So many savages that they would

never lack," the governor reported to Lisbon, "even if we were to

cut them up in slaughter-houses." He did not balk at punishing those who

dared interfere with his plans, and he took such action not for his sake alone

but for the glory that should be promised King João in this land. "The

Pious," as the king was now called, had made it clear that this time he

would tolerate no nonsense from his native subjects.

![Caramaru, Fish Man, and Princess Paraguacu [8]](../images/Caramuru_Paraguacu.jpg) Caramaru,

"Fish Man," the sole survivor of the wreck of an Indies ship off the

shoals north of the Bahia in 1510, had been found between the rocks by the Tupinamba.

Caramaru had lived among the savages for more than two decades before the arrival

of Dom Francisco Coutinho, one of Dom João's donatários. Dom Francisco

had lost his life under a slaughter club. The Tupinamba had spared Caramaru,

not only because he was their friend, but also because his wife, Paraguaçu,

"Big River," was the daughter of their most powerful chief.

Caramaru,

"Fish Man," the sole survivor of the wreck of an Indies ship off the

shoals north of the Bahia in 1510, had been found between the rocks by the Tupinamba.

Caramaru had lived among the savages for more than two decades before the arrival

of Dom Francisco Coutinho, one of Dom João's donatários. Dom Francisco

had lost his life under a slaughter club. The Tupinamba had spared Caramaru,

not only because he was their friend, but also because his wife, Paraguaçu,

"Big River," was the daughter of their most powerful chief.

![Mem de Sa, Governor, Brazil [9]](../images/memdesa.jpg) Medium

in height, slightly plump and stiff-limbed, Governor Mem de Sá was not

given to displays of emotion. Months before, when he learned that the savages

had slaughtered his son, Fernáo, twenty years old he'd reacted by withdrawing

to his quarters to pray for the child he'd personally ordered into battle.

Medium

in height, slightly plump and stiff-limbed, Governor Mem de Sá was not

given to displays of emotion. Months before, when he learned that the savages

had slaughtered his son, Fernáo, twenty years old he'd reacted by withdrawing

to his quarters to pray for the child he'd personally ordered into battle.

"Compel

them to come in!" the Gospel of St. Luke urged, and it had become

the rallying cry of the Jesuits.

"Compel

them to come in!" the Gospel of St. Luke urged, and it had become

the rallying cry of the Jesuits.

Compel them....Inacio glanced at José de Anchieta, a young brother standing with the group. Brother José was eager to comply with this shibboleth. Anchieta wa often sickly. But his zeal was militant and inspiring, and his craving for the harvest of souls insatiable.

![Foundation of Sao Paulo, Oscar Pereira da Silva [11]](../images/FoundationofSaoPaulo.jpg) Padre

Nobrega, Anchieta and others had gone back to Piratininga. Nine miles from the

mameluco settlement, on January 25, 1554, they had established the aldeia of

São Paulo de Piratininga.

Padre

Nobrega, Anchieta and others had gone back to Piratininga. Nine miles from the

mameluco settlement, on January 25, 1554, they had established the aldeia of

São Paulo de Piratininga.

![Tupi Woman and Child, Albert Eckhout, 1641/1644 [12]](../images/woman_tupinanba.jpg) "They

should fear — the Tupiniquin. If they but knew the lessons taught the

Tupinambá in these lands."

"They

should fear — the Tupiniquin. If they but knew the lessons taught the

Tupinambá in these lands."

The lessons Anchieta spoke of had been raids led by Mem de Sá against the Bahia Tupinambá, not successfully pacified since the day of Tomé de Sousa, when they had eaten the degredados. One especially arrogant elder, Bloated Toad had mocked the new governor as the creature of a king who was a baby: He, Bloated Toad, was man and would do as he had always done, and to prove it, he'd sent his warriors to seize a plump enemy, who was slain by him and eaten in the middle of his clearing. "Come and judge me!" Bloated Toad dared Mem de Sá.

![Brazilian Indian family, 16th century [13]](../images/Tupinambavillage2.jpg) The

Tupiniquin simply refused to move. To Padre Inácio's pleas, they responded

by showing that their fields were still productive, the thatch on their houses

new, the clay of the great pots their women fashioned for beer as fresh as the

brew they held. Their people had slain no Long Hairs — why should they

move?

The

Tupiniquin simply refused to move. To Padre Inácio's pleas, they responded

by showing that their fields were still productive, the thatch on their houses

new, the clay of the great pots their women fashioned for beer as fresh as the

brew they held. Their people had slain no Long Hairs — why should they

move?

![Manioc, Albert Eckhout [14]](../images/eckhout_manioc.jpg) The

horrors of plague and pox were raging at the malocas of natives not yet contacted

by the Portuguese. Crushed as they were by the diseases, they had faced yet

another torment — famine.

The

horrors of plague and pox were raging at the malocas of natives not yet contacted

by the Portuguese. Crushed as they were by the diseases, they had faced yet

another torment — famine.

"If you could see the poor things," said a father reporting on the condition of these refugees," seeking a bowl of manioc. They arrive at a plantation begging the owner to take their children as slaves in exchange for a single meal."

![Dom Sebastiao, King of Portugal [15]](../images/SebastianPortugalwiki.jpg) In

1578, King Sebastião "the Desired," a flaxen-haired large-limbed

twenty-year-old filled with a sense of grand destiny, assembled sixteen thousand

men and set out to conquer Morocco.

In

1578, King Sebastião "the Desired," a flaxen-haired large-limbed

twenty-year-old filled with a sense of grand destiny, assembled sixteen thousand

men and set out to conquer Morocco.

![Alcacer-Quibir Battle, 1578 {16]](../images/Alcacer-Quibir.jpg) At

Alcacer-Quibir, south of Tangiers, the force was destroyed and Dom Sebastião

himself slain. Less than fifty escaped.

At

Alcacer-Quibir, south of Tangiers, the force was destroyed and Dom Sebastião

himself slain. Less than fifty escaped.

The rout at Alcacer-Quibir had not ended in the sand of North Africa. Dom Sebastião died a bachelor, and the heir to the Portuguese throne was his aged grand-uncle, Cardinal Henriques. Eighteen months after his succession, Henriques died. Phillip II of Spain now claimed and won the throne of Portugal.

Not only had the Portuguese lost the independence of their homeland and empire; they gained new enemies — the English and the Dutch — with whom their new king, Phillip II, had long quarreled.

![Caatinga, the White Forest of Brazil [17]](../images/Caatinga_000.jpg) On

the seventh day of their journey, their route took them out of the forest into

open country, where the luxuriant vegetation quickly began to give way to an

arid cover of spiky bushes and stunted plants. Clumps of bush, stick-dry and

dead; spiny cactus bent into grotesque shapes; gnarled branches of stripped

trees — caatinga, "the white forest," the natives called

this ash-gray landscape.

On

the seventh day of their journey, their route took them out of the forest into

open country, where the luxuriant vegetation quickly began to give way to an

arid cover of spiky bushes and stunted plants. Clumps of bush, stick-dry and

dead; spiny cactus bent into grotesque shapes; gnarled branches of stripped

trees — caatinga, "the white forest," the natives called

this ash-gray landscape.

![Jean Baptiste Debret, 1834, Soldados índios de Mogi-das-Cruzes. [1]](../images/DebretBandeirante.jpg) The

bandeiras of medieval Portugal had been small raiding parties sniping at the

Moors; at São Paulo, a bandeira was an organized force that set out for

an expedition into the sertão, the backlands.

The

bandeiras of medieval Portugal had been small raiding parties sniping at the

Moors; at São Paulo, a bandeira was an organized force that set out for

an expedition into the sertão, the backlands.

![Antonio Raposo Tavares, oil, Manuel Victor [2]](../images/RaposoTavaresoil.jpg) Antônio

Raposo Tavares was thirty years old. He had come to São Paulo ten years

ago from the plains of Alentejo, in central Portugal, where he spent his youth

among the wheat fields and orange groves. Raposo Tavares was a tall, handsome,

bearded man, powerfully built, decisive and confident. A born leader who devoutly

believed he was destined to make great discoveries in Brazil, he was passionately

eager for adventure.

Antônio

Raposo Tavares was thirty years old. He had come to São Paulo ten years

ago from the plains of Alentejo, in central Portugal, where he spent his youth

among the wheat fields and orange groves. Raposo Tavares was a tall, handsome,

bearded man, powerfully built, decisive and confident. A born leader who devoutly

believed he was destined to make great discoveries in Brazil, he was passionately

eager for adventure.

![Joao Ramahlo shows Martim Afonso de Sousa the road to Piratininga, Benedito Calixto [3]](../images/JoaoRamalho.jpg) Valentim

Ramahlo's family belonged to a great clan of mamelucos related to João

Ramahlo, the castaway who had settled the high plateau long before the Jesuits

Nobrega and Anchieta arrived to establish São Paulo de Piratininga.

Valentim

Ramahlo's family belonged to a great clan of mamelucos related to João

Ramahlo, the castaway who had settled the high plateau long before the Jesuits

Nobrega and Anchieta arrived to establish São Paulo de Piratininga.

The

colegio of the Jesuit fathers stood upon a good vantage point above the Piratininga

plain. Here, too, were the Franciscans and Benedictines, their churches raised

with care. But most of São Paulo was a slum of mud-and-wattle hovels

planted along dirt-strewn streets.

The

colegio of the Jesuit fathers stood upon a good vantage point above the Piratininga

plain. Here, too, were the Franciscans and Benedictines, their churches raised

with care. But most of São Paulo was a slum of mud-and-wattle hovels

planted along dirt-strewn streets.

![Inquisition in Portugal, 1685, copper engraving [5]](../images/InquisitioninPortugal.jpg) The

Inquisition had not been established in Brazil, but occasionally Visitors were

sent to examine the faith of the colonists and to investigate reports that Brazil

was a haven for Jewish exiles and lax New Christians. The belief that there

were significant numbers of crypto Jews was exaggerated, but Portugal had always

been more tolerant of Jews than had Spain, and groups had come to the colony,

particularly those with expertise in the sugar industry.

The

Inquisition had not been established in Brazil, but occasionally Visitors were

sent to examine the faith of the colonists and to investigate reports that Brazil

was a haven for Jewish exiles and lax New Christians. The belief that there

were significant numbers of crypto Jews was exaggerated, but Portugal had always

been more tolerant of Jews than had Spain, and groups had come to the colony,

particularly those with expertise in the sugar industry.

![Philip IV, Spain, Diego Valazquez [6]](../images/PhilipIV.jpg) Philip

II of Spain, son of the emperor Charles V and Isabella of Portugal, had taken

the Portuguese crown in 1581....

Philip

II of Spain, son of the emperor Charles V and Isabella of Portugal, had taken

the Portuguese crown in 1581....

And now there was Philip IV, horseman, hunter, lover of art and letters, who, when not engaged in these pastimes, involved his country — and Portugal — in a vicious and exhausting conflict with England, France and Holland.

![Indian slaves, Brazil. Rugendas [7]](../images/IndianSlavesRugendas.jpg) The

Paulistas had been slave-raiding in these lands since long before Amador's birth,

leading thousands of Carijo back to São Paulo.

The

Paulistas had been slave-raiding in these lands since long before Amador's birth,

leading thousands of Carijo back to São Paulo.

![Bandeirante equipped for war, Brazil [8]](../images/bandeirantesequipment.jpg) Bernardo

da Silva's upper body was encased in a sleeveless leather jacket quilted and

padded with cotton twill thick enough to withstand an arrow. Below the waist

he wore cotton breeches and boots that extended above the knee. On the belt

that secured the quilted carapace was a good-sized pouch, a powder horn and

ramrod for his musket, and a sword, knives and small battle-ax

Bernardo

da Silva's upper body was encased in a sleeveless leather jacket quilted and

padded with cotton twill thick enough to withstand an arrow. Below the waist

he wore cotton breeches and boots that extended above the knee. On the belt

that secured the quilted carapace was a good-sized pouch, a powder horn and

ramrod for his musket, and a sword, knives and small battle-ax

![Trinidad de Parana Reduction, Jesuit mission ruins, Paraguay [9]](../images/trinidad.jpg) São

Paulo itself did not have a population as large as this Jesuit town. The Carijo

lived in houses ninety feet long, partitioned into separate family quarters.

Walking with the Paulistas toward the reduction square, Amador counted nine

rows of houses on either side of the main thoroughfare.

São

Paulo itself did not have a population as large as this Jesuit town. The Carijo

lived in houses ninety feet long, partitioned into separate family quarters.

Walking with the Paulistas toward the reduction square, Amador counted nine

rows of houses on either side of the main thoroughfare.

!["Dead Christ" at the Paraguayan Reduction of San Ignacio Guazœ was carved in the 1600s by a Guaraní artist [10]](../images/deadchrist.jpg) For

ten years, Amador da Silva marched with bandeiras that destroyed the remaining

eight reductions of the province of Guiara and forced the fathers and the remnant

of their great congregations to flee south in the direction of Buenos Aires.

For

ten years, Amador da Silva marched with bandeiras that destroyed the remaining

eight reductions of the province of Guiara and forced the fathers and the remnant

of their great congregations to flee south in the direction of Buenos Aires.

![Bandeirante House, Brazil [11]](../images/BandeiranteHouse_000.jpg) The

homestead was a one-storied whitewashed building, its rammed earth walls two

feet thick. In the front were two large rooms, on either side of a spacious

verandah... the roof made with half-round reddish tiles, pagoda-like, with graceful

sloping sides.

The

homestead was a one-storied whitewashed building, its rammed earth walls two

feet thick. In the front were two large rooms, on either side of a spacious

verandah... the roof made with half-round reddish tiles, pagoda-like, with graceful

sloping sides.

![Dutch seize Oilinda, 1630 [12]](../images/DutchseizeOlinda.jpg) A

Dutch armada reached Pernambuco, landing troops on a beach just north of Olinda

— then a prosperous city of eight thousand settlers — and seizing

the capital the same evening.

A

Dutch armada reached Pernambuco, landing troops on a beach just north of Olinda

— then a prosperous city of eight thousand settlers — and seizing

the capital the same evening.

![Jean-Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (or Johann Moritz von Nassau-Siegen), 1603-1679, was the general governor of the Dutch colonies in Brazil. This oil-painting portrait in 1637 is preserved at Siegerlandmuseum of Siegen.[13]](../images/Johann_Moritz.jpg) Those

attending this night's festa included no less a personage than the governor

of New Holland, Johan Maurits, count of Nassau Siegen. Capable solder and fine

administrator, Maurits also showed himself to be a visionary. He assembled a

group of forty-six scientists, scholars, writers and artists from all over Europe

and solemnly declared their assignment: "to reveal to the world the wonders

of paradise."

Those

attending this night's festa included no less a personage than the governor

of New Holland, Johan Maurits, count of Nassau Siegen. Capable solder and fine

administrator, Maurits also showed himself to be a visionary. He assembled a

group of forty-six scientists, scholars, writers and artists from all over Europe

and solemnly declared their assignment: "to reveal to the world the wonders

of paradise."

![Frans Post, Recife and Mauritsstad 1640 [14]](../images/ReceifePanorama.jpg) Opposite

Recife on an island formed by two rivers, the governor was building a new capital,

Mauritsstad, a well-fortified town with broad avenues and two canals.

Opposite

Recife on an island formed by two rivers, the governor was building a new capital,

Mauritsstad, a well-fortified town with broad avenues and two canals.

![Brazilian Sugar Plantation, 1667, Frans Post [15]](../images/Engenho_com_capela.jpg) Amador

was in the grand house on the plantation he has seen from the ridge overlooking

the valley — Engenho Santo Tomás, the property of Fernão

Cavalcanti, of an old and illustrious Pernambucan family.

Amador

was in the grand house on the plantation he has seen from the ridge overlooking

the valley — Engenho Santo Tomás, the property of Fernão

Cavalcanti, of an old and illustrious Pernambucan family.

![Henrique Dias, Brazil's first black general [16]](../images/HenriqueDias2.jpg) Ribeiro

told Amador that during the guerilla war, he had served with two units, the

first commanded by Felipe Camarão, a Potiguara chief, and the other by

Henrique Dias, a free black.

Ribeiro

told Amador that during the guerilla war, he had served with two units, the

first commanded by Felipe Camarão, a Potiguara chief, and the other by

Henrique Dias, a free black.

"I was there when Henrique Dias lost his hand," Ribeiro said. "Oh the brave man — with a sword in the hand that remained, howling like a wild dog, for the Hollanders to come to him...

![Felipe Camarao, artist, Victor Meireles [17]](../images/Victor_Meirelles02.jpg) "And

Dom Camarão —

he deserves to be made a fidalgo for his services — Dom Camarão

saw Affonso Ribeiro chop up three Hollanders, one after the other, with my machete."

"And

Dom Camarão —

he deserves to be made a fidalgo for his services — Dom Camarão

saw Affonso Ribeiro chop up three Hollanders, one after the other, with my machete."

![Tapuya Indians Dancing, Albert Eckhout [18]](../images/TupayaIndiansEckhout.jpg) In

late November 1640, after an overland journey of four weeks from Engenho Santo

Tomás, Amador and Segge reached the malocas of Nhandui, a powerful Tapuya

chief

In

late November 1640, after an overland journey of four weeks from Engenho Santo

Tomás, Amador and Segge reached the malocas of Nhandui, a powerful Tapuya

chief

![Young Tapuya Indian Woman, Albert Eckhout [19]](../images/TupayaWomanGoodEckhout.jpg)

Segge cupped his chin in his hand, the tip of his index finger touching his nose. "What more does it need?"

"You're painting a cannibal — a flesh-eating, bone-grinding, mother of pagans. Show this."

One morning four weeks after their arrival, Amador saw that Segge had made some changes in the painting of the Tapuya girl: One hand, resting on her knee, grasped a severed human hand. Segge had given her a basket, which she carried on her back, and protruding from the basket was a human foot.

"Bravo!" Amador exclaimed. "Exactly! A savage for the world to see!"

![Golden Raft model, Lake Guatavita, Bogota, possible El Dorado legend source [20]](../images/Muisca_raft_Legend_of_El_Dorado_Offerings_of_gold.jpg) "There

is a lake close to the lands of the warrior women, where the boys are sent.

Once a year they hold a ceremony. One boy is chosen to be Son of the Sun. When

the Great rains end and the Sun is strongest, this Spirit Man is covered with

gold dust. He is taken to the lake and bathes in it."

"There

is a lake close to the lands of the warrior women, where the boys are sent.

Once a year they hold a ceremony. One boy is chosen to be Son of the Sun. When

the Great rains end and the Sun is strongest, this Spirit Man is covered with

gold dust. He is taken to the lake and bathes in it."

"The man the Spaniards call 'El Dorado."

![Paresi woman, Brazil [21]](../images/Paresi-Mulher.jpg)

Amador and Segge spent ten months, from September 1642 until July 1643, with the Paresí. Here, as Segge said, they were gods come down from Olympus...

"Who were the warrior women, Kaimari?" Amador asked eagerly.

"In the beginning, a race of women ruled earth. A man's only use was to lie with them. The girls born to these women were trained as ferocious warriors. The boys? No one knows what happened to the boys."

![Tordesilhas Line [22]](../images/Tordesilhasmap2.jpg) "What

is your purpose in these lands...of Spain?"

"What

is your purpose in these lands...of Spain?"

"The purpose?"

"You have traveled far beyond the line," Juan Baptista added. (The line he referred to was the Tordesilhas demarcation of the world dominions of Portugal and Spain.)

"Certainly, Padre," Amador admitted. "Through lands held by savages. The purpose?" He nodded. "We sought Paraupava," he said, using the Tupi-Guarani word for the fabled lake of gold.

"And have you found it?"

Amador plucked at his deerskin breeches. "Had we discovered El Dorado would we be standing before you as beggars?"

![Madeira Mamore River, rapids near Guajara Mirim [23]](../images/GuajaraMirim.jpg) "Guajara

Mirim," he said, "Little Falls."

"Guajara

Mirim," he said, "Little Falls."

The canoes were moving with a strong current, some twenty yards from the left bank. The river was almost a mile wide, its flow north broken in several places by rocky, wooded isles.

![Capuchin [24]](../images/613px-Capuchin_Costa_Rica.jpg) A

colony of potbellied spider moneys fretted in the branches above them, chattering

defiantly and baring their teeth in mocking grins. Coming downriver, Amador

and Segge had seen monkeys of every description: capuchins, their hairstyle

similar to the capuche of the Franciscan; the uakari, another monk of the forest;

saki, boasting a splendid hood of hair; and the tiny squirrel monkeys, often

one hundred together.

A

colony of potbellied spider moneys fretted in the branches above them, chattering

defiantly and baring their teeth in mocking grins. Coming downriver, Amador

and Segge had seen monkeys of every description: capuchins, their hairstyle

similar to the capuche of the Franciscan; the uakari, another monk of the forest;

saki, boasting a splendid hood of hair; and the tiny squirrel monkeys, often

one hundred together.

![Shrunken Head [25]](../images/450px-Shrunken_head.jpg) The

grateful Mundurucu gave Amador and Segge each a shrunken head.

The

grateful Mundurucu gave Amador and Segge each a shrunken head.

The skull and brains were carefully removed, the skin gently daubed with urucu, the lips sealed with fiber strands. The head was filled with sand and left until it dried and shrank to the size of a man's fist. Then it was ready to be worn around the neck of the warrior who had taken it: a medallion of honor.

![Amazon River sunset [26]](../images/AmazonSunset.jpg) The

surface of the river would be painted in a way no mortal artist would emulate,

passing through a spectrum of shades, from soft pinks and mauves to a fiery

blaze that turned the waters of the Rio das Amazonas into molten gold.

The

surface of the river would be painted in a way no mortal artist would emulate,

passing through a spectrum of shades, from soft pinks and mauves to a fiery

blaze that turned the waters of the Rio das Amazonas into molten gold.

![Sir Walter Raleigh [27]](../images/WalterRaleigh.jpg) English

and Irish parties made persistent attempts to gain a foothold on the northern

banks of the lower Rio das Amazonas, the 1620 expedition having been led by

Captain Roger North, an officer who'd served with Sir Walter Raleigh. Four years

later, Abel O'Brien's cousin Bernard O'Brien settled a group of colonists 250

miles upriver at a place called Pataui, "Coconut Grove."

English

and Irish parties made persistent attempts to gain a foothold on the northern

banks of the lower Rio das Amazonas, the 1620 expedition having been led by

Captain Roger North, an officer who'd served with Sir Walter Raleigh. Four years

later, Abel O'Brien's cousin Bernard O'Brien settled a group of colonists 250

miles upriver at a place called Pataui, "Coconut Grove."

![Urubu, Brazil, vulture {28]](../images/Urubu.jpg) On

Death-Bird Island, the urubu, which had taken flight at the first burst of musket

fire, now began to circle back to their territory. And into the channel streamed

piranha.

On

Death-Bird Island, the urubu, which had taken flight at the first burst of musket

fire, now began to circle back to their territory. And into the channel streamed

piranha.

Men

who lived to tell of this day would never forget the horror. The blood attracted

thousands of the deep-bellied fish, their triangular shaped teeth snapping at

those who thrashed about frantically to escape this ultimate enemy. The piranha

feasted and the mighty Rio das Amazonas became a river of blood.

Men

who lived to tell of this day would never forget the horror. The blood attracted

thousands of the deep-bellied fish, their triangular shaped teeth snapping at

those who thrashed about frantically to escape this ultimate enemy. The piranha

feasted and the mighty Rio das Amazonas became a river of blood.

![Zumbi of Palmares, aka Ganga Zumba [30]](../images/493px-Zumbidospalmares.jpg) For

ten years João Angola had served his master, Menezes, but when the Dutch

invaded Pernambuco in 1630, João and forty slaves from Engenho Formosa

ran into the sertão. As a fugitive, João Angola received another

set of names from the Portuguese, a corruption of "Nganga Dzimba we Bahwe":

"Ganga Zumba"

For

ten years João Angola had served his master, Menezes, but when the Dutch

invaded Pernambuco in 1630, João and forty slaves from Engenho Formosa

ran into the sertão. As a fugitive, João Angola received another

set of names from the Portuguese, a corruption of "Nganga Dzimba we Bahwe":

"Ganga Zumba"

![Quilombo, plan, a Brazilian runaway slave citadel [31]](../images/planofquilombo.jpg) Not

only had Ganga Zumba remained free these past fifteen years; he had attracted

fourteen thousand runaways to his refuge. His capital, Shoko, was home to six

thousand people, their huts lying along three avenues, each of which was a mile

long.

Not

only had Ganga Zumba remained free these past fifteen years; he had attracted

fourteen thousand runaways to his refuge. His capital, Shoko, was home to six

thousand people, their huts lying along three avenues, each of which was a mile

long.

![Great Zimbabwe [32]](../images/Great-Zimbabwe.jpg) He

knew that Nayamunyaka envisaged walls and towers such as existed at Great Zimbabwe,

but ten years of sporadic effort had produced no more than forty feet of loose

foundation. Still the site was called Dzimba we Bahwe ("Place of Stones.)

He

knew that Nayamunyaka envisaged walls and towers such as existed at Great Zimbabwe,

but ten years of sporadic effort had produced no more than forty feet of loose

foundation. Still the site was called Dzimba we Bahwe ("Place of Stones.)

![Capoeira, or The War Dance, artist J.M. Rugendas [33]](../images/CapoeiraRugendas.jpg) The

two contestants now wheeling and dancing toward each other were the same young

men who had trapped the bird as a gift for the Nganga...The rhythms of the berimbau

died away. The two men stopped their sparring and turned to face Nhungaza, their

ebony skins glistening with sweat, their chests heaving.

The

two contestants now wheeling and dancing toward each other were the same young

men who had trapped the bird as a gift for the Nganga...The rhythms of the berimbau

died away. The two men stopped their sparring and turned to face Nhungaza, their

ebony skins glistening with sweat, their chests heaving.

![Monte das Tobacas battle site [34]](../images/Monte_das_Tabocas.jpg) Monte

das Tobacas rose two hundred feet above ground level and offered a good vantage

point in all directions. To the west and south of the hill flowed the Tapicura

River; on the eastern side lay an old track used by brazilwood loggers.

Monte

das Tobacas rose two hundred feet above ground level and offered a good vantage

point in all directions. To the west and south of the hill flowed the Tapicura

River; on the eastern side lay an old track used by brazilwood loggers.

![Casa Forte, engenho Dona Ana Paes, Foundation Joaquim Nabuco archives [35]](../images/casaforte.jpg) Haus

and his officers were in the main residence of this old and substantial plantation,

the property of a widow, Dona Ana Paes. The dwelling, mill, slave quarters,

and outbuildings were sited similarly to those at Santo Tomás; the big

house was also double-storied but was built upon stilts.

Haus

and his officers were in the main residence of this old and substantial plantation,

the property of a widow, Dona Ana Paes. The dwelling, mill, slave quarters,

and outbuildings were sited similarly to those at Santo Tomás; the big

house was also double-storied but was built upon stilts.

![Battle of Guararpes, April 1648 [36]](../images/BattleofGuarapes.jpg) At

Pernambuco in April 1648, the patriots had defeated five thousand Hollanders

and their native troops at the Guararapes, a series of hillocks outside Recife.

At

Pernambuco in April 1648, the patriots had defeated five thousand Hollanders

and their native troops at the Guararapes, a series of hillocks outside Recife.

![Muleteer, Brazilian reenactor [37]](../images/tropeiro.jpg) Far

behind the slaves, Olímpio Ramahlo took up the rear of the column, with

forty mules and their drivers. Amador's prejudice against his son's pack animals

had lessened when he saw their surefootedness and the great burdens they were

capable of carrying.

Far

behind the slaves, Olímpio Ramahlo took up the rear of the column, with

forty mules and their drivers. Amador's prejudice against his son's pack animals

had lessened when he saw their surefootedness and the great burdens they were

capable of carrying.

![Panning for Gold [38]](../images/gold_rush.jpg) "I

feel it in my bones, Olímpio,"

Procopio would say, and laughing, he would slap his wooden leg — carved

by himself and adorned with two wide bands of silver filigree."There are

riches here! Your father climbs the highest peaks, but the treasure is down

here. Not emeralds. Not silver. Gold!"

"I

feel it in my bones, Olímpio,"

Procopio would say, and laughing, he would slap his wooden leg — carved

by himself and adorned with two wide bands of silver filigree."There are

riches here! Your father climbs the highest peaks, but the treasure is down

here. Not emeralds. Not silver. Gold!"

![Bandeirante gold prospecting expeditions [39]](../images/Mapa2.jpg) Again

and again they had found traces — enough to pay for their expedition —

but it had taken eleven years before they came to a river, where a single day's

work with the bateia produced one thousand oitavos! Procopio was back there

now, guarding their precious claim, for many others had become convinced that

gold in great quantities was to be found in the highlands of Terra do Brasil.

Again

and again they had found traces — enough to pay for their expedition —

but it had taken eleven years before they came to a river, where a single day's

work with the bateia produced one thousand oitavos! Procopio was back there

now, guarding their precious claim, for many others had become convinced that

gold in great quantities was to be found in the highlands of Terra do Brasil.

![Death of Fernao Dias Paes Leme [40]](../images/deathofpaesleme.jpg) "Your

father..."

"Your

father..."

Olímpio turned to look at Amador's still form. Immediately he knew. "Now! Here? So near the end?"

"He had his triumph," Procopio Almeida said quietly.

And so, in his sixty-seventh year, with his pouch of emeralds at his side, Amador Flôres da Silva died. In the sertão.

Book Four: Republicans and Sinners

![Mafra Monastery, Portugal [1]](../images/MafraMonasteryandCastle.jpg) Luis

Fialho stood with his back to the others and was looking at Mafra. "Dear

God, what a majestic pile! What would those Paulistas searching for El Dorado

say? What would the believe but that here, before their eyes, was the palace

of El Dorado!"

Luis

Fialho stood with his back to the others and was looking at Mafra. "Dear

God, what a majestic pile! What would those Paulistas searching for El Dorado

say? What would the believe but that here, before their eyes, was the palace

of El Dorado!"

Marcelino Augusto laughed. "Every stone paid for with the gold and diamonds of Brazil."

![Punishment of Slave, Brazil, Jean-Baptiste Debret [2]](../images/DebretPunishmentofaSlave.jpg) Often

Luis Fialho's lyrical contemplations had been followed by dark melancholy at

the thought of Brazil. He had spoken on America as sensuous and corrupting.

It was in Luis Fialho's carefully chosen words, "A hell for blacks, a purgatory

for whites."

Often

Luis Fialho's lyrical contemplations had been followed by dark melancholy at

the thought of Brazil. He had spoken on America as sensuous and corrupting.

It was in Luis Fialho's carefully chosen words, "A hell for blacks, a purgatory

for whites."

![Diamond diggings, 18th century Brazil [3]](../images/Diamond1Juliao.jpg) Crown

officials proclaimed a "Forbidden District," some 130 miles in circumference,

east of the range known as The Spine. A miner caught extracting diamonds without

the king's authority could be thrown into jail or banished to Angola; illegal

possession by a slave could bring up to four hundred lashes, often after forced

ingestion of a purge of Malgueta pepper to flush out any gems he had swallowed.

Crown

officials proclaimed a "Forbidden District," some 130 miles in circumference,

east of the range known as The Spine. A miner caught extracting diamonds without

the king's authority could be thrown into jail or banished to Angola; illegal

possession by a slave could bring up to four hundred lashes, often after forced

ingestion of a purge of Malgueta pepper to flush out any gems he had swallowed.

![Marquis de Pombal [4]](../images/350px-Louis-Michel_van_Loo_003.jpg) The

man sat sideways at one of the mahogany tables, an elbow resting on the surface...As

arresting as his piercingly intelligent hazel eyes were the cleft in his chin,

emphasizing the well-shaped mouth, and a white wig that flowed to his shoulders.

He was Sebastião José Carvalho e Melo, and on this day in October

1755, no man in Portugal save the king was more powerful.

The

man sat sideways at one of the mahogany tables, an elbow resting on the surface...As

arresting as his piercingly intelligent hazel eyes were the cleft in his chin,

emphasizing the well-shaped mouth, and a white wig that flowed to his shoulders.

He was Sebastião José Carvalho e Melo, and on this day in October

1755, no man in Portugal save the king was more powerful.

![Padre Antonio Vieira, Jesuit, Brazil [5]](../images/vieira.gif) "Vieira

did not lie," Carvalho e Melo said dryly, referring to the Jesuit who had

labored along the Rio das Amazonas. "'Two million dead,' Vieira wrote sixty

years ago. How many more since Vieira's day?" He shook his head."No,

Vieira did not lie about the butchers of the Amazon," he repeated. "And

what would he say if he were alive to see aldeias where hundreds are kept as

serfs, where they do forced labor on plantations and roam the forest for products

to enrich the Jesuits?"

"Vieira

did not lie," Carvalho e Melo said dryly, referring to the Jesuit who had

labored along the Rio das Amazonas. "'Two million dead,' Vieira wrote sixty

years ago. How many more since Vieira's day?" He shook his head."No,

Vieira did not lie about the butchers of the Amazon," he repeated. "And

what would he say if he were alive to see aldeias where hundreds are kept as

serfs, where they do forced labor on plantations and roam the forest for products

to enrich the Jesuits?"

![Ribeira Palace and Square in Lisbon, Portugal. [6]](../images/PacoRibeira-18thCentury.jpg) The

palaces of the king and the powerful Corte-Real family dominated the waterfront

on the west side of the Terreiro do Paço, the palace square; east of

the square was a magnificent quay, and behind it the customs building.

The

palaces of the king and the powerful Corte-Real family dominated the waterfront

on the west side of the Terreiro do Paço, the palace square; east of

the square was a magnificent quay, and behind it the customs building.

![View of Alfama from the Miradouro of Santa Luzia in Lisbon, Portugal [7]](../images/Alfamaclip.jpg) Lisbon

had a medieval, congested appearance, its most striking feature its ninety convents,

forty parish churches, and several basilicas ....Paulo and Luis Fialho were

guests at Dona Clara's four-story house on a precipitous street northeast of

Rossio Square in the heart of the city.

Lisbon

had a medieval, congested appearance, its most striking feature its ninety convents,

forty parish churches, and several basilicas ....Paulo and Luis Fialho were

guests at Dona Clara's four-story house on a precipitous street northeast of

Rossio Square in the heart of the city.

![Lisbon Earthquake [8]](../images/1755_Lisbon_earthquake.jpg) Ten

seconds later, there was a devastating shock. The houses opposite Paulo began

to sway; the floor beneath him vibrated so violently that he struggled to keep

his balance ....A thundering in the earth dulled Paulo's perception of these

noises. Terremoto! The word crashed through Paulo's senses. "Earthquake!"

Ten

seconds later, there was a devastating shock. The houses opposite Paulo began

to sway; the floor beneath him vibrated so violently that he struggled to keep

his balance ....A thundering in the earth dulled Paulo's perception of these

noises. Terremoto! The word crashed through Paulo's senses. "Earthquake!"

![Lisbon earthquake tidal wave [9]](../images/Lisbon1755_000.jpg)

The force of the earthquake produced monstrous tidal waves that raced into the mouth of the Tagus from the southwest. Ships were torn from their moorings and splintered against wharves and quays. Small craft ;laden with refugees crossing to the south bank were swallowed up in the whirlpools.

![Looters hanged, Lisbon earthwake 1755 [10]](../images/Lisbon1755hangingdetail.jpg) Few

were innocent; the quakes that leveled Lisbon seemed to have cast up from the

depths an assembly of assassins, cutthroats, robbers and thieves.

Few

were innocent; the quakes that leveled Lisbon seemed to have cast up from the

depths an assembly of assassins, cutthroats, robbers and thieves.

![Lisbon ruins 1755 [11]](../images/Ruins.jpg) Gazing

toward a district where the fires were intense, Carvalho e Melo asked,"

When London burned, did the Englishmen abandon it?"

Gazing

toward a district where the fires were intense, Carvalho e Melo asked,"

When London burned, did the Englishmen abandon it?"

"No, Excellency."

"I will rebuild Lisbon," Carvalho e Melo said.

![Casa Grande, Gilberto Freyre [12]](../images/CasaGrande.jpg) The

mansion stood on the high ground that six generations of Cavalcantis had occupied

since Nicolau and Helena built that first forlorn and forbidding blockhouse...It

was not only its imposing size that gave the Casa Grande distinction but also

the harmony with which it blended into the landscape.

The

mansion stood on the high ground that six generations of Cavalcantis had occupied

since Nicolau and Helena built that first forlorn and forbidding blockhouse...It

was not only its imposing size that gave the Casa Grande distinction but also

the harmony with which it blended into the landscape.

![Sugar Mill, Henry Koster, Brazil [13]](../images/Koster.jpg) Beyond

the Casa Grande, the ground sloped gradually toward a river, beside which were

located the sugar works, the distillery, and the senzala, the main

slave quarters.

Beyond

the Casa Grande, the ground sloped gradually toward a river, beside which were

located the sugar works, the distillery, and the senzala, the main

slave quarters.

![Casa Grande, masters and slaves [14]](../images/fazenda.jpg) The

intimate relationship between the slaves of the house and the sinhá

and sinhazinha, as the slaves called Senhora Cavalcanti and her

daughters, was sometimes subtle and secretive, with confidences no Cavalcanti

male was every likely to hear.

The

intimate relationship between the slaves of the house and the sinhá

and sinhazinha, as the slaves called Senhora Cavalcanti and her

daughters, was sometimes subtle and secretive, with confidences no Cavalcanti

male was every likely to hear.

![Vaqueiros, cowboys of Brazil [16]](../images/Aboio1.jpg) From

his birth, when the woman who bore him rested on a a soft hide, to burial, when

death in a far place might bring internment in a rough shroud, the vaqueiro

existed in a world of leather.

From

his birth, when the woman who bore him rested on a a soft hide, to burial, when

death in a far place might bring internment in a rough shroud, the vaqueiro

existed in a world of leather.

![Brazilian slaves in stocks, Jean Debret [16]](../images/stocksdebret.jpg) "I

won't have you whipped or branded, but you'll spend your days and nights in

the stocks. When you've served your punishment, you'll work like a young ox

to fill the place of the slave who died because of you."

"I

won't have you whipped or branded, but you'll spend your days and nights in

the stocks. When you've served your punishment, you'll work like a young ox

to fill the place of the slave who died because of you."

![Slave Punishment, Brazil [17]](../images/slave_mask.jpg) After

ten days, Onias lost heart. Then he had sought to end his life in a way known

to the 'Ngola of Angola: Sinking to his knees, he had consumed great mouthfuls

of red dirt.

After

ten days, Onias lost heart. Then he had sought to end his life in a way known

to the 'Ngola of Angola: Sinking to his knees, he had consumed great mouthfuls

of red dirt.

Graciliano took charge of the treatment of Onias, who was forcibly administered a powerful emetic. After three days he recovered.

Onias was led to the blacksmith. Here Onias was fitted with a contraption to prevent him from eating dirt: an iron mask that had apertures for his eyes and nose but not his mouth.

![18th century Jesuit father [18]](../images/342px-Brazil_18thc_JesuitFather.jpg) It

was December 23, 1759. A week ago, a messenger from the Superior at Recife had

brought the order that the two priests leave Rosário in compliance with

the royal edict.

It

was December 23, 1759. A week ago, a messenger from the Superior at Recife had

brought the order that the two priests leave Rosário in compliance with

the royal edict.

Leandro Taques spent eleven days along the road from Rosário to Recife. He intended no more than atonement for his sins and omissions, but in this last and darkest hour for the Jesuits of Brazil, the long walk of Leandro Taques was a small triumph.

![African women in Brazil,18th century, [19]](../images/Debretescravas_negras_de_diferentes_nacoes_imagelarge.jpg) Today

there were thirty Yoruba slaves at the engenho, less than one-fifth of the Cavalcanti

slaves. Despite their small number all at the senzala held Ama Rachel in veneration

for she was a high priestess of the Yoruba, the yalorixa.

Today

there were thirty Yoruba slaves at the engenho, less than one-fifth of the Cavalcanti

slaves. Despite their small number all at the senzala held Ama Rachel in veneration

for she was a high priestess of the Yoruba, the yalorixa.

The

Yoruba had not abandoned the gods of their people but had come to liken them

to the divinities and saints worshipped by the Portuguese. Thus they identified

Olurum with the Almighty; his son Oxala, known for his purity with Jesus Christ;

and Yemanja, whom they begged to carry them safely across the ocean, with Our

Lady.

The

Yoruba had not abandoned the gods of their people but had come to liken them

to the divinities and saints worshipped by the Portuguese. Thus they identified

Olurum with the Almighty; his son Oxala, known for his purity with Jesus Christ;

and Yemanja, whom they begged to carry them safely across the ocean, with Our

Lady.

![Brazilian slave lashed at pelourinho, Jean-Baptiste Debret [20]](../images/DebretPelourinho.jpg) Black

Peter, the carpenter, received the first of 100 lashes. "Jesus, Jesus,

Jesus....where is Black Peter who was free?" The knout stung his back.

"Jesus, Jesus.... here I am a peça!"The thongs struck low across

his back. The mulatto shifted position. The next blow landed on his right shoulder

blade. "I was free with the padres."

Black

Peter, the carpenter, received the first of 100 lashes. "Jesus, Jesus,

Jesus....where is Black Peter who was free?" The knout stung his back.

"Jesus, Jesus.... here I am a peça!"The thongs struck low across

his back. The mulatto shifted position. The next blow landed on his right shoulder

blade. "I was free with the padres."

![Capitao do Mato, Rugendas [21]](../images/capitaodematarugendas.jpg)

For three weeks after the slaughter of Elias Souza Vanderley and Little George, militia patrols hunted for the fugitives extending their searches west and south toward the sertão but finding no trace of them.

![Plantation chapel, Pernambuco [22]](../images/Engenho4.jpg) The

boards of the choir loft creaked as Padre Viana crossed to the right gallery.

Three quarters of the way along the balcony, he stopped and stood with his hands

on the railing, glancing down into the chapel, where several candles had been

lit.

The

boards of the choir loft creaked as Padre Viana crossed to the right gallery.

Three quarters of the way along the balcony, he stopped and stood with his hands

on the railing, glancing down into the chapel, where several candles had been

lit.

Bartolomeu Rodrigues was down on his knees, beside Paulo's coffin. His sobbing was interrupted by long silences.

"Hear his weeping, O Lord," Viana whispered. "Console his suffering, I beseech thee."

!["Monsoon" convoy leaves for Brazilian goldfields [22]](../images/AlmeidaMoncao.jpg) In

both spirit and boldness, the convoys were a continuation of the mighty pathfinding

adventures of men like Amador and Raposo Tavares. A voyage of 3,500 miles to

the mining camps, the seasonal river-borne convoys were called "monsoons."

In

both spirit and boldness, the convoys were a continuation of the mighty pathfinding

adventures of men like Amador and Raposo Tavares. A voyage of 3,500 miles to

the mining camps, the seasonal river-borne convoys were called "monsoons."

![Surgical instruments made by Pierre Fauchard during the 18th century [23]](../images/Pierre_Fauchard.jpg) Silva

Xavier always traveled with his dental equipment.

Silva

Xavier always traveled with his dental equipment.

"Courage, Senhor Benedito," André said. He flashed his own white teeth, "Joaquim has attended me. There's little pain."

"O my little Jesus."