Burton Williams

1931-1936 age 14-18

“Most anything was better than sitting home and doing nothing.”

I caught a freight train and rode in a boxcar from Wilburton, Oklahoma to Elk City, where I picked cotton for six weeks. My brother and I were 14 and 16 years old. We worked pretty hard for the cotton grower and thought we had made enough money for some clothes and shoes. When we told him we were quitting and going home, he said, "Well, you have 35c each coming."

So we hopped a freight train in town. It was November and had been getting real cold. We rode to Oklahoma City, got off and followed a bunch of older fellows down to the hobo jungle.

It was raining and cold and there must have been 20 men there around 6:00 p.m. A nicely dressed man walked up and asked if we were hungry. Of course, everyone was, so he said follow me up to this little cafe.

We all did and he bought a bowl of soup for each of us.

There was one fellow who said "Mister, I don't like soup, could I have a piece of pie?"

The man told him if he didn't like soup, he wasn't hungry.

Would look to the west while in Oklahoma and see red clouds most of the day. People would say the red in the west was a sign the world was coming to an end. It was frightening to say the least.

CALIFORNIA

C.D. White

On one stop in Colorado, we were very hungry, so we went into a cafe and ordered most expensive meal and pie for dessert. I asked the fellow if he would sell us a whole pie. Yes he said and disappeared in the back of cafe. When he came back we were on a train heading east. May the Lord forgive me!

CALIFORNIA

Carl Heberling

I was 25 in 1932. Worked as plumber apprentice in Youngstown, Ohio steel town. When the Depression hit, steel mills shut down throwing thousands out of work.

I got a job on a farm for $1 a week and my room and board. I decided to hitchhike to Florida, where my folks lived.

On the road I was picked up by a man and a woman in a Model A Ford. They were armed and had a gun in the glove compartment. Whenever we would come to a small town, they drove only back streets. At that time I did not know it was Bonnie and Clyde. They were well dressed and clean and I thought them very nice looking.

Not long ago my wife and I drove over to Las Vegas and they had their bullet marked car in which they were killed on display.

As I looked at the car a strange feeling came over me. It was the car I had ridden in.

CALIFORNIA

Chester Clever

19 +

1933-1939

Leaving home because too many mouths to feed. Six younger children plus two younger aunts and uncles after mother died and father left to look for work. No jobs in Shippensburg, PA

Riding across Raton Pass from New Mexico into Colorado, the grade was so steep they had to cut the train in half and take one half up and then come back.

There was a stream with trout. Another hobo and I took off our shirts and dammed up the stream and caught about 120 trout. Other hobos pitched in. We had bacon, corn meal, potatoes, bread and our fish while waiting for our train to move on.

In Lima, Ohio, the yard cop made you clean out your pockets, take any money you had. Pointed me to highway and said hitchhike.

I ran from Yuma, AZ bull, bumped my head, fell, and he worked me over with tight pigskin gloves.

One time I worked two hours cutting a pile of wood. I was given a sandwich with thin bread and one slice of bacon.

I gave it back saying, “Dad, you’d better take this back, you need it more than I do.”

”Today, always have plenty of food in the house. I get upset if stock gets low.”

CALIFORNIA

Clarence Lee

"People don't want to talk about their past, but if you don't know where you've come from, then you don't know where you're going."

Age 15 rode around Louisiana, gone from home for 18 months.

"Bought" his father out of sharecropping debt

Trainman put him off train because he would be lynched in next town. An alleged rape had taken place.

"In those days it wasn't a crime for whites to kill a black. Just another dead black..."

CALIFORNIA

D.Rodgers

A townie’s view

Greybull, Wyoming

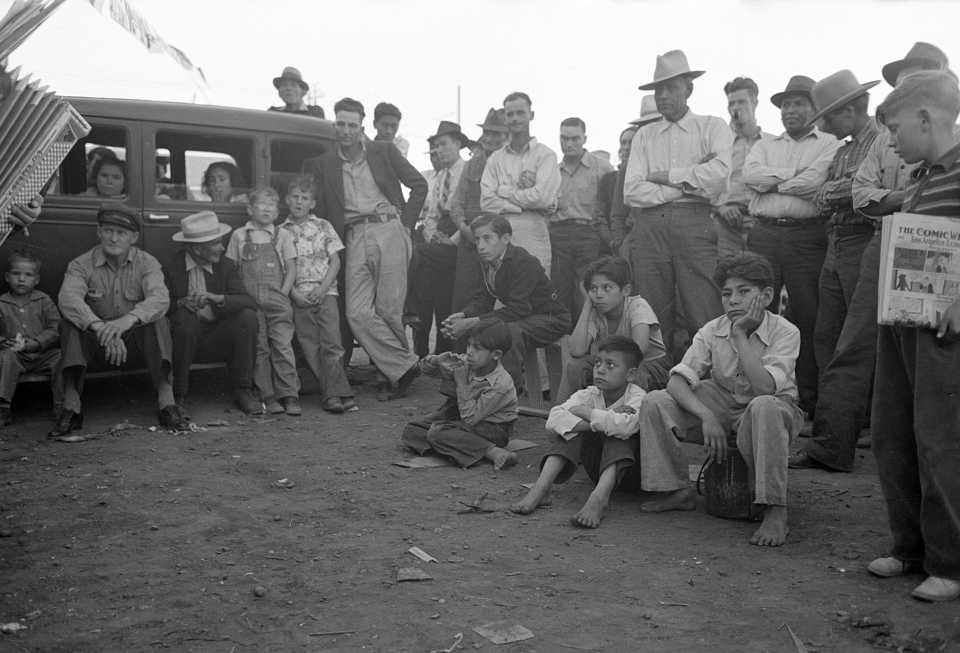

The northbound freights came to an almost complete stop near the south boundary of the city and all the non fare paying passengers jumped off.

The people who lived in the first house they would reach south of the town told my parents one day ninety six people came to their door asking for a handout. They were hoping for four more to make it an even hundred.

Almost all men of that era carried a Bull Durham sack with them. It was a common sight to see hoboes checking the sidewalks and gutters in the business district for cigarette butts. They would break open the butts and put the tobacco in their Bull Durham sacks. You could buy 100 papers for a dime.

Tucson AZ was a bad place to spend the winter. There were so many transient persons descending there in the winter, the police were constantly checking on the rail yards. If a person could not show they had a residence or a job they were charged with vagrancy. When they could not pay the fine they were sent to jail to work out the sentence. If after 24 hours after being released the person was not out of town, he was picked up and charged again. Some people spent a good deal of winter in jail.

CALIFORNIA

Darwood Drake

(Looking Back © Darwood Drake, 1989)

The CCC, the Civilian Conservation Corps, started by President Franklin Roosevelt, was just getting under way that hot summer of 1933. They were to have two hundred men to a camp, and to be run something like an Army Company, although without guns, ammunition, etc. The object being to build roads, dams, and bridges, and to provide employment for the idle youth who were crowding the streets during those hopeless days of the Depression.

One weekend I told Dad I wanted to join the CCC's, and he agreed it might not be a bad idea. We understood I was to get board, room, and medical care plus $30 per month; of said $30, $25 was to be sent home to assist the family. Word was that to pass the physical test required, one's teeth had to be in top shape, and I knew I had problems there.

Dad gave me what he could spare, and I took the $4.00, hitched a ride to Williston and found a dentist. When I told him I had $4.00 and hoped to have my teeth in good enough shape to pass the CCC examination; he just said, "Don't worry, son, we'll see that you pass that test." and he spent all afternoon fixing my teeth.

I passed the physical test and was sent to a CCC camp.

Arkansas was a different world for North Dakota farm boys, and we had to get used to the Southern Drawl, the different type of food (grits, corn pone, etc.) and the slower way of living.

Locke was in the very heart of the Arkansas Ozarks, and we saw shacks that people lived in, ramshackle places, with livestock running freely in and out of the same shack families lived in.

This was also the heyday of Pretty Boy Floyd and other famous and notorious bank robbers. It was rumored that one of Floyd’s hideouts was in our area, and he was a sort of hero to many of the poverty stricken families that lived in that area.

The company was involved in thinning trees, building dams and roads, and clearing brush; and while we were at Locke we took part in various activities for amusement. Bob Johnston's brother had gained quite a reputation as a tap dancer, and had taught Bob many of his routines.

So Bob started a tap dancing class and there were about ten who took part; none of us weighing less than 160 pounds, and several who were over 200. It was quite a sight to see, ten uncoordinated men jumping up and down, trying to tap to "The Sidewalks of New York". It's a good thing the practice shed was in an isolated area, as the noise was thunderous.

Later on, several of the boys did fairly well, and they danced in the camp show we had just before leaving in the spring.

We were taken by truck to Ft. Smith whenever we could get leave, or even on weekends, and there was a lot to do, what with dances, movies and drinking.

Across the river was a Dance-A-Thon, which was a sort of endurance contest to see who could keep dancing the longest time without stopping. The marathon dance contests were being held all over the country at this time; another objective being to entertain the spectators, and the Dance-A-Thon at Moffit was like the others. We often went to see how our favorites were making out, and also to see who had dropped out.

One evening Red Erickson, two other guys, and myself, got bored with watching the performance, and decided to do something else. We knew the location of a local bootlegger, found him, and bought some liquor. After a few drinks we decided to return to the Dance-A-Thon; when all at once I felt a hard object pressing into my back, and a loud voice said, "Get your hands up!".

We all complied, and were marched off to a small one-room jail in the near vicinity, after they had searched us and found the liquor. They identified themselves as Deputy Sheriffs, although we found out later it was just a racket.

We were in their phoney jail by about 10 p.m., and at about midnight the same two "deputies" came back and asked us how much money we had. Among the four of us we had about $12, and they said that wasn't very much, but they were willing to let us go if we gave it to them and never came back to this part of Oklahoma again.

Well, they let us go, and as we left, we headed for the Dance-A-Thon to go back over the regular auto bridge. But the deputies wouldn't let us do that, they insisted we cross over the railroad bridge.

It was dark, the railroad bridge was high, we had to walk between the rails, and we could hear the river roaring far below. If that wasn't bad enough, when we were about halfway across, we could see the lights of a train coming.

All we could do was crawl out on the timbers that stuck out over the sides, and hang on. The other two guys were completely in states of panic, so Red and I had to hang on to them as well as try to balance ourselves. However, the train finally passed and we got back to Ft. Smith and caught the last truck for camp.

Dennis Olsen

Hobo "Egypt’s" good advice: “There’s an eastbound rattler coming through at noon. Hop it, go home, finish school, get some learnin’. There’s plenty time to be a hobo later on if that’s what you wanna be. But, if you don’t want to be a hobo, you’ll need schoolin’ ”

CALIFORNIA

Doc Harmon

I was in a jungle and a short heavy bum was singing with a beautiful voice. He sang ballads and railroad sons. Called himself the Wayfaring Stranger. I found out later it was Burl Ives.

I was forced to jump out of a moving box car in Texas or get my skull busted by a railroad cop called Texas Slim. He was a man who showed no pity and loved to hit men with the big club he carried. Anyone who bummed in the state of Texas has heard of Texas Slim.

I was down to three cents in Gallop, NM heading for LA. A buddy and I were walking along highway 64 when I saw a sow's ear purse on the shoulder of the road.

It had no ID and no one showed up to claim it. It had a little over $2 in coins. The best meal we had in meals.

CALIFORNIA

Donald Claude

Very poor. We were 12 children, seven boys and five girls.

"The black people in the south were better about feeding us than the white. A black man gave me a coconut and I didn’t know how to eat it.”

CALIFORNIA

Donald Kopecky

What led you to leave home?

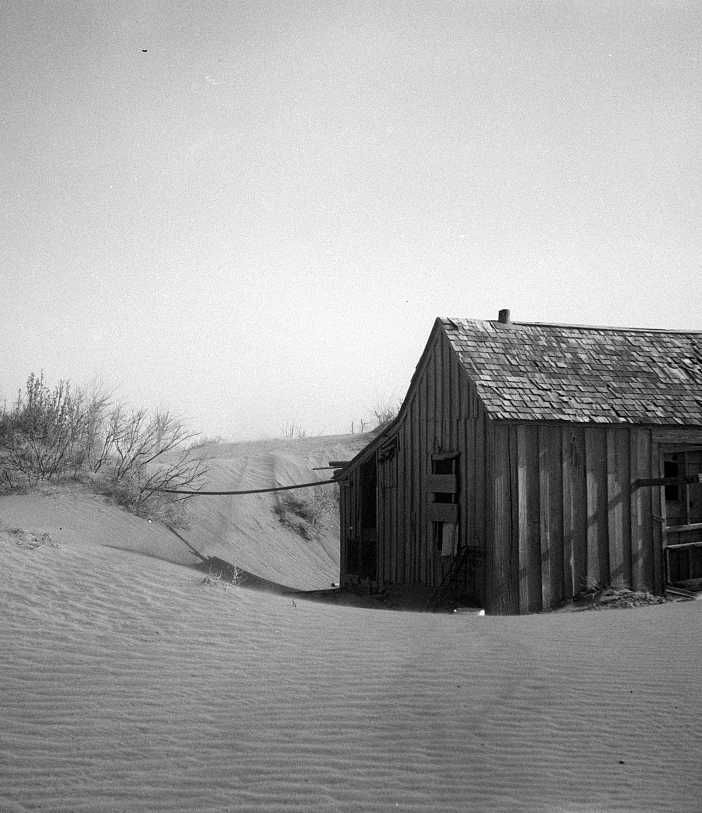

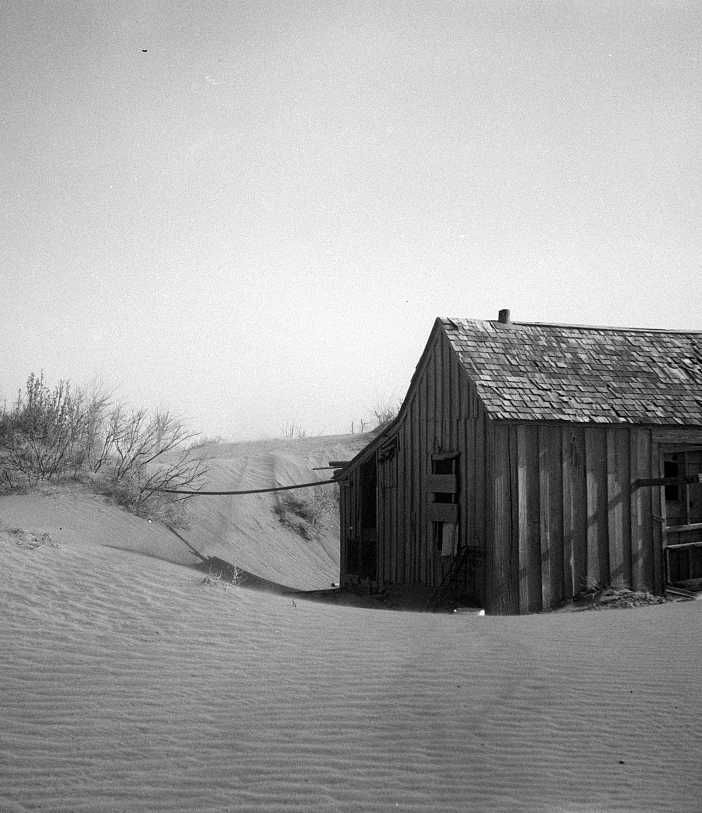

Hoover was president. The Depression was at its peak. On the farms of the mid-west the Dust Bowl wiped out the crops for a number of years in succession. In the summer of 1931 during school vacation, I rode the boxcars to Idaho where I got a job digging potatoes.

On the way home when the potato harvest was finished all of the riders in the boxcar I was in were robbed. Got home nearly starved two days later.

I worked for a bachelor one summer during vacation feeding cattle. My pay was $15.00 a month and beans.

After graduation from high school I joined the navy.

How did you survive - get food, shelter?

Being farm oriented I knew by instinct where farm gardens were most likely to be. By watching from the boxcar or gondola as a freight came into a town it was just a matter of walking back to a place after dark that appeared likely to have a garden. You could generally find vegetables, melons, corn, etc. This all went into a mulligan usually under the railroad bridge. I once milked a cow at midnight out in the pasture at a dairy. I raided garbage cans but they were a poor source of food.

All drifters like myself migrated with the weather. This was natural since the crops to be harvested grew in the summer and were harvested in the fall.

In Phoenix, Ariz. I slept in an orange orchard for three weeks waiting for a job to start. At that time milk was delivered door to door by a milkman. His supply was a horse-drawn milk wagon. The horse walked down the street as the milkman went house to house delivering milk, cream, butter and even eggs.

I located a bakery and by watching learned that the delivery trucks brought in day old bakery goods from their routes in the evening. This was dumped into a bin in a locked yard at the back of the bakery. Later in the night a truck from a hog farm came and picked it up for hog feed. I loosened a board from the fence that surrounded the yard, carefully replacing it each time I went in to restock my supply.

It was too hot to stay in the orchard during the daytime so I would go down to the courthouse and watch a murder trial that was taking place. It was cool there.

The trial had something to do with a newsman who was on a hot lead that was taking him into some of the higher political levels of politics in Arizona. Someone blasted him into orbit by putting a bomb under the seat of his car.

I lived those three weeks on milk, cream, butter, eggs, bread cake, rolls, oranges, grapefruit; and usually had the Arizona Republic or Phoenix Gazette for the morning news.

People met on the road:

0dell "Red" Goza. Big, strong, mean, a bully, loved to fight and a hard man to handle. If the going got too tough he always had a long bladed shiv which he didn't hesitate to use. Red had spent some hard time in a military brig in Oklahoma while in the army. He was about thirty years old when I first knew him.

I knew he was a character to steer clear of. This was verified one night in a bar called Elzie's at Six Points in the outskirts of Phoenix, Ariz. It was payday and the bar was full of fruit tramps.

There was also a pudgy little lettuce buyer in the bar from somewhere in the east, who, when he drank too much became something of a pompous ass. When he bought a drink for himself he always flashed a big roll of bills while searching leisurely through it for a small one to pay the bar tender. He was loud-mouthed and spoke in a demeaning manner about the lettuce bums and fruit tramps he had to associate with as a buyer. Ninety percent of those in the bar were fruit tramps.

It was pretty obvious that that guy was going to be separated from his roll before the night was over.

Red was in the bar drinking as usual that night. He spotted the roll the guy was flashing. The patsy got up and went to the rest room. Needless to say Red was right behind him. If Red hadn't been close behind someone else would have beat him to the patsy. As usual the juke box was blaring, and the bar flies were trying to talk louder than the music.

I happened to be sitting fairly close to the restroom door. Shortly after Red got in there I heard some slamming around and "help, "help" coming from inside, then everything was quiet.

Red came out, a grin on his face, and left the bar. It was after midnight. A short time later another patron went into the restroom. He came rushing out yelling at the bartender that there was a man down in the restroom and bleeding all over the floor. The bartender called the police. I left

Red told me later that the roll the guy had wasn't as big as it looked and his wrist watch was just a cheapie. Red was never questioned by the police.

About six months later in Sacramento I retrieved a Sacramento Bee from a garbage can. A little item inside the paper said an itinerant by the name of Odell Goza had killed another resident of Hooverville, a hobo jungle on the Sacramento River.

Witnesses said that an argument developed between the two over the victim drinking more than his share from the wine bottle they were sharing. I never saw or heard of Red again but of one thing I'm sure, he wasn't going to die of old age.

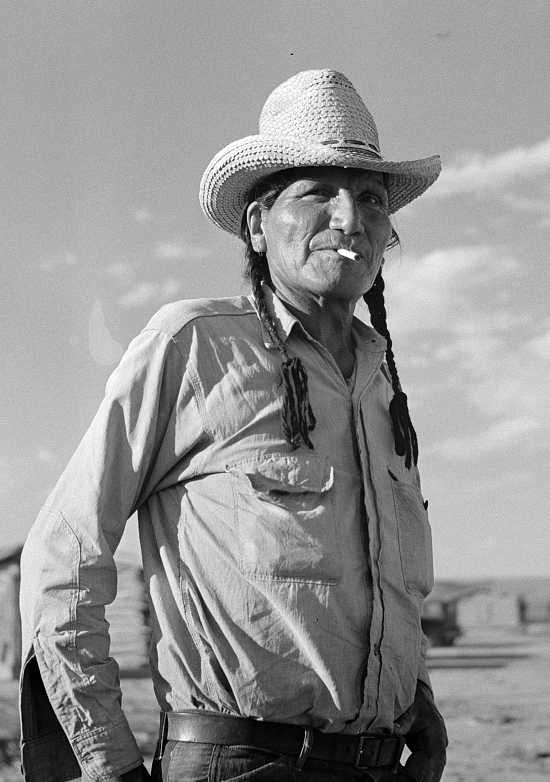

Jim Foss, a Hopi Indian from the reservation south of Phoenix Ariz. I met Jim when we were both cutting table grapes in a vineyard near Lodi, California. Jim was a true outdoorsman. He spent most of his life out in the open. He didn't know how old he was (I guessed him to be about sixty) and he was totally uneducated, yet he was smarter than many people I have known. Jim s total worldly possessions consisted of his clothes, blanket and an old Model A.

Jim talked to the grapevines, the birds, the sun, the earth. They were his friends. He slept in the vineyard, his blanket over his shoulders, hat pulled down low as he leaned against a fence post, tree or any convenient back-rest. He didn't like his old Model A. If it balked he didn't know how to fix it. The tires were recaps, mostly bald with boots in them.

As we cut grapes I told him of the ranch that I had once worked on in Montana. Jim had never traveled far from the reservation. The more I told him of the ranch and Montana, Idaho, and the great northwest the more interested he became. When we finished cutting grapes we went to Sacramento where I changed the oil in his car (we used reclaimed oil, 11c a quart) bought a recap for a spare and started for Montana. Jim was a terrible driver so I did the driving.

Jim enjoyed every mile of that trip. He called the southeastern part of Oregon, Idaho and Montana a highly complementary Indian word which I don't remember. The Nez-Perce, native to that country, call it the Land Of The Big Sky.

We went to work on the ranch where I had worked before. Jim knew nothing about horses or driving a team. And most of those horses were wild and mean. Yet somehow Jim in his own way of talking to them, in the way he treated them, and the calming effect that he had on all animals, managed to handle his team and do more work with out abusing them than any of the other men got out of their teams.

When we finished in Montana we went to Grand Junction, Colorado for a short stint of work then to Phoenix. The packing shed in Phoenix shut down for a few days so Jim went back to the reservation for a visit. When the shed restarted and Jim didn't show up the boss drove out there to tell him to come back to work. Friends of Jim on the reservation told the boss Jim had died. They said they didn't know he was sick. They found him one morning, blanket over his shoulders, hat pulled down, leaning against a desert shrub. Jim had never went to a doctor in his life. He died the way he wanted to.

What kind of disappointments did you have when trying to find work?

1. In Colorado a farmer promised three of us jobs putting up alfalfa when it was ready in about a week. We camped out in the woods waiting for the job to start then when it was ready he told us there were enough local men who needed work and that he wouldn't need us after all.

2. In Seattle, Washington where the same three of us bought jobs with Alaska Fisheries. (Buying jobs was a common practice during the depression.) When we got to the Fisheries office we learned that we had to join the union at a fee of fifty dollars each, and that after we joined we would be hired by seniority. We had neither the fifty dollars or the seniority to be hired. When we went back to the job-seller to try to get our money back ($15.00) he had gone out of business.

3. Working on a dairy outside Seattle baling straw. A hard headed German was our boss. He was always mad about something. One morning he couldn't get the old Fordson Tractor that we used to power the baler started. He kicked the iron front wheel as hard as he could, then hopped around on one foot for a while swearing in German all the time. When his foot quit hurting he grabbed a pitchfork and swung it at the tractor hitting the exhaust stack in such a way that the handle broke and the tine end flew between me and one of the other crewmen. We all got into the pickup and went back to the dairy where they put the baling crew to hauling manure out of the cow corrals.

The four of us who made up the baling crew decided to go to the owner of the dairy that night and tell him what had happened and that we would rather not work for the German anymore. The result was all four of us were fired. The owner said that the man had worked faithfully for him for seven years and that we were only drifters who would quit as soon as we got a payday.

4. World War II was coming on. I saved up enough money to take a six weeks' course in aircraft sheet metal work in a school in San Francisco. The school guaranteed a job if you completed the course in a satisfactory manner. I completed the course with good grades. When I went to the main office to see about the guaranteed job they got me one as a bus-boy in a college dorm. When I complained they shrugged it off saying in effect, "We guaranteed you a job. There it is, take it or leave it."

Ever injured or see anyone injured while riding the rails?

A young boy about twelve or thirteen years old was traveling with a man who appeared to be his father. The boy had been hit on the side of the head with a sap by a yard bull in Cheyenne, Wyo. His right eye had been knocked completely out of its socket and was dangling down on his cheek. The father was trying to get help for him. Finally a police car came and took him away.