Broad commentary on Michener's draft Chapter V of The Covenant, "The Trekboers." Specific comments appear on the 139 manuscript pages; this overview was prepared for discussion at the revision stage

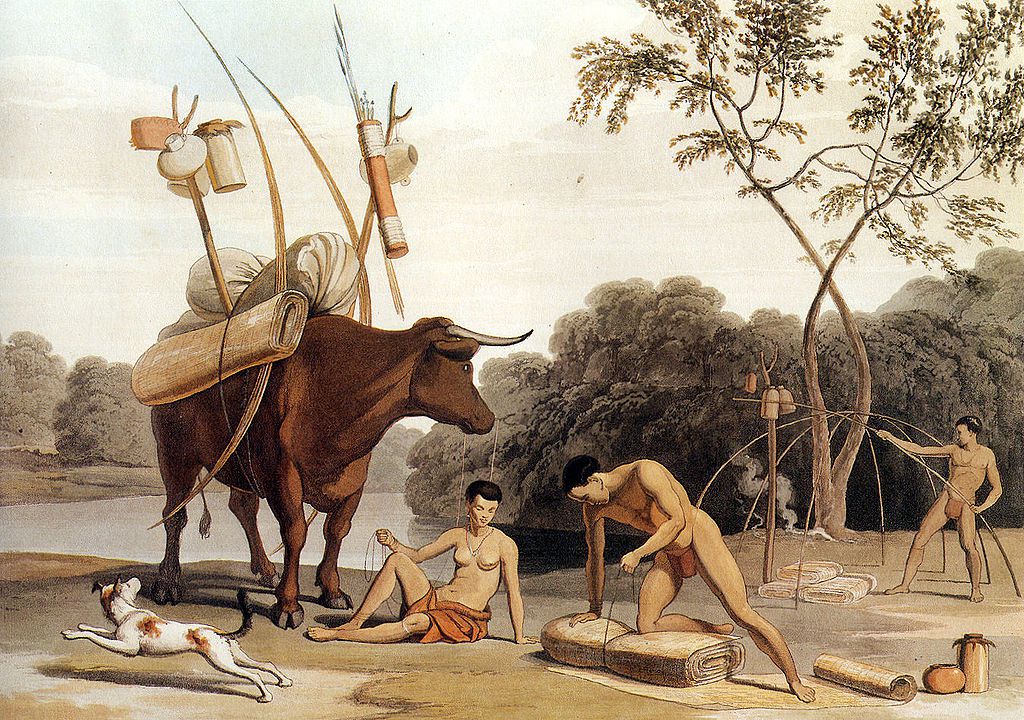

The trekboers were nomadic pastoralists, forerunners of the Voortrekkers, the Dutch pioneers who forsook the Cape Colony and trekked north in the 1830s.

The picture given of trekboers (most sources use lower case 't') - "wandering farmers who carelessly tilled a piece of land for nine or ten years, then abandoned it for a better piece of new land forty miles farther east... they practiced the most abusive type of agriculture" - misses important aspects of the trekboer phenomena.

The trekboers were nomadic pastoralists; what land they 'tilled' was usually for their private needs and minimal. Some pointers from Keppel-Jones:

Three groups of colonists we are concerned with:

• Inhabitants of Cape Town - townsmen (as distinct from Compagnie officials)

• Settled wheat and vine farmers - stable and fairly civilized

• Pastoralists of the interior - veeboere i.e. trekboers

"Life on the cattle posts had great attraction for young men. It was a life of adventure, of brushes with San and Khoikhoi, of plunder perhaps, of release from the trammel of civilization.

"Newer farmers were to a large extent the old farmers sons and ticket-of-leave soldiers accustomed to frontier life. Pastoralist was not tied to one spot. Families in the snow covered Roggeveld or Nieuwveld Mountains trekked down in winter and spring to the Karoo plains and returned to the high altitudes before heat and drought of summer. Children who had been rocked to sleep by the jolting of the wagon grew up with the thought of migrating to the north or east to find homes for themselves. The trekboer had adapted himself to the pace of the ox."

Important to consider the land the trekboer moved into with his cattle and sheep. Monica Cole has, for example, a chart of drought stricken areas in 1926-39. Aside from the southwestern Cape and an area encompassing the fertile Garden Route, rest of province was declared drought-stricken for 30 to 60 months, and a major portion -typical trekboer territory - for 60 months and over.

South Africa is periodically affected by severe and prolonged droughts. The rainless years of the 30's culminated in the disastrous year of 33/34 when stock losses ran into the millions. The bane of the farmers is the country's unreliable and unpredictable rainfall. Over much of the country large fluctuations are the rule rather than the exception. Years with a below average figure are more common than years with an above-average rainfall.

Even in Simon van der Stel's time, there were farmers who farmed exclusively in cattle and sheep, and grazing licenses had been issued to people without fixed property, Van der Stel discouraged it by legislation, but his placaaten were ineffective in times of drought. Willem Adriaan van der Stel (son) encouraged rather than opposed cattle farmers - in areas too far from the Cape market to be of practical agricultural use. (No doubt also a good thing considering his attempts to grab monopoly on grain and wine for himself and his cronies.)

Some of the farmers who obtained grazing licenses also possessed farms, but the further east they left the settled areas behind, the more often they possessed nothing but loan land. Often the grazing rights on a farm were extended for a number of years. On such farms they built houses known as the opstal. Not being the owner of the land, when they left they sold the opstal to the next person who obtained the grazing rights. This was to be known as the loan place system; in July 1714, Governor de Chavonnes and the Council of Policy setting 12 rix dollars as rent. Boundaries of the colony continued to be extended - 1745 to Great Brak River - but farmers continued to move further east with their cattle. In the north, too,where no boundaries had been determined, the trek into the interior began to swing east because water was scarce.

In a memorial to his son in 1699, Simon van der Stel observed that some farmers were pleading 'soil exhaustion' as an excuse to move to new lands where they only sowed enough for themselves and made a living by stock barter. 'Should you be weak enough to give way to such sinister tricks, the whole of Africa would not be sufficient to accommodate and satisfy that class.' Although throughout the century many stock-owners lived permanently in the agricultural areas, and used distant land for pasture only, more and more became trekboeren, graziers who lived permanently on grazing farms, migrating seasonally for pasture, or moving on altogether as 'land became exhausted'.

Some led such nomadic lives that they never settled down anywhere and lived in ox wagons. Stock-farming also needed fewer laborers than agriculture, and both the Khoi Khoi and San made excellent herdsmen, who were employed for little more than their upkeep. The adventurous frontier life, free from the petty exactions of Cape Town officials, attracted colonial born children, who mostly could not afford to become traders or lodging house keepers in Cape Town or vegetable, wine or grain farmers in western Cape, and were too ill-educated to enter the limited ranks of the Civil Service or the professions and too proud to become farmhands or artisans.

It was possible to make a living as a grazier since there was a constant demand for mutton, trek-oxen for transport and ploughing, and pastoral by-products like soap, butter and tallow. After the beginning of the 18th century the government no longer resisted the development of full-time sheep and cattle farmers because it realized that "the spreading out of the inhabitants with their cattle is the principal reason that meat can be delivered so cheaply to the Compagnie and private individuals.

Oxford History of SA: "Though loan places could not be bequeathed they were actually held in families for generation." Spilhaus: "If the trekboer succeeded he counted his wealth in stock, and had not one grazing place but several. If he failed he became at best a bywoner - a squatter on another man's land In exchange for being able to squat, he acted as foreman or something of the kind. If even this modicum of discipline irked him, the family became gypsies, living in their tented wagons and in temporary shelters. From these people came in time a thriftless, spineless type known as Poor Whites, men who met poverty with idleness, translated the privilege of a white skin into even more idleness, retreated in the face of competition and described inertia as independence." Cronje and Venter (Die Patriargale Familie) add: "Cattle and sheep farming required little capital; from a century before to a quarter after the Great Trek a team of oxen, a small herd and a rifle were enough for a young man to live independently in the interior."

Thompson calculated that it took 2,200 rix dollars to set up like this. In practice though every son was from birth a cattle farmer (or sheep) through the practice of setting aside for every child certain animals, so that he had a small herd by the time he was ready for marriage. And if he wasn't so lucky, it was not difficult to get stock from someone else and run it on basis of 50 per cent of offspring. Daughters also had stock set aside so that herd was doubled at marriage. Barter, hunting and the ivory trade added to income. The grazing population soon came to include men whose livelihood demanded constant movement from place to place.

To several, such movement would be a familiar process. In southern Germany, Switzerland and north Wales, the seasonal migration of shepherds and herdsmen between plain and mountain was of considerable antiquity. In the SA interior the severity of the climate, with intense winter cold in regions such as the Roggeveld and the Sneeubergen, and the prevalence of drought, forced a high percentage of farmers into category of trekboeren (See further notes in Hattersley.) Bad as the nomadic life might be socially and culturally, trekking to well-watered areas to avoid grievous stock losses in times of drought could not be avoided.

Some additional points: Meat was staple food, bread a rare luxury, some grew a little fruit and wheat. Some families made annual journey to Cape, others ever 3 to 4 years, a few only once in a lifetime. Trip needed to buy gunpowder, cloth, coffee, a few implements, some brandy etc. They spoke Cape Dutch or The Taal, later to be called Afrikaans.

The emphasis (in chapter) should be on the herds, on trekking periodically, on nomadic pastoralism rather than abusive agriculture. The herds and flocks raises question of contact with Cape Town. No reference to this beyond one trader in four years: cannot see that unless they lived as outcasts from society, they could survive without some form of trading. Rooi Valck (a character in The Covenant) comes much closer to trekboer image than any of the Van Doorns.

The next problem closely aligned to the above comes from various references to slaves in the first instance and the absence of references to Hottentots/Bushmen (Khoikhoi/San) in the second. The trekboers were low on slaves, high on Hottentot labor, the latter being especially adept at cattle tending etc. Laws forbade the enslavement of Hottentots, but it is accepted that the distinction between slavery and freedom hardly connoted any practical advantage to the 'free' Hottentots. Still, can't call them slaves in the sense a U.S. reader would understand.

There is a gap in the total absence from 1702 till late in the manuscript of any reference to the Khoikhoi captaincies. We know that there were at least 10 of these units between Cape Town and the Xhosa lands, and that there was extensive cattle barter between them and the Boers - and that their power broke down till the enfeebled constituents took up as laborers with the Boers.

When we come into contact with the Xhosa it should be remembered that there was a well developed relationship between Xhosa-Khoikhoi and San over centuries, resulting in inter-marriage, Khoi-Xhosa chiefdoms, trade, etc. so that it's impossible that Xhosa men would know so little about the Hottentots.

One has to compensate for the fact that, with rare unbiased exception, the popular white South African view favors the "smallpox eradication of Khoikhoi" and "deserted wilderness" theory/ euphemism. Even Muller, whom I respect, is able in one paragraph to say, a) "in the first half of the eighteenth century the cattle farmer who had become a trek farmer encountered virtually no resistance on his advance into the interior" and b) "In 1734 the company's furthest outpost was erected in the Riet Valley on the Buffelsjagte River. Its purpose was to protect the cattle farmer and Hottentots against the rapacious Bushman."

On the first meeting between white/black may consider personalizing it further to Van Doorn family because of historic evidence of prior contact. On general statements about Dutch being ignorant of fact that to the east lay a major society we know from Van Riebeeck's diary, way back in the 1650's, that even he was aware of the Xhosa i.e. 'Chobona'.

Dikkop (a character in The Covenant) creates problems in places with his lineage and one wonders whether he should not simply be a Hottentot, second generation in contact with the Boers, his simplified background affording a chance to deal with the problem of the disappearing Hottentots.The Xhosa section runs into difficulties because various customs of other tribes are attributed to the Xhosa. And situations exist which, while maybe okay in fiction, would be an anathema to any Xhosa tribesman.

For example, tribal structure: All Xhosa tribes owe allegiance to chief of senior tribe as paramount, agreed. This does not mean that paramount can interfere in internal affairs of constituent tribe, nor is their appeal to his court from those of various chiefs. His advice is sought on matters pertaining to the royal family; his paramountcy determines first celebration of First Fruits ceremony etc. The basic political unit is tribe, a group of people occupying territory under an independent chief. Failure to recognize that a paramount chief of Xhosa had no effective power over the minor tribes led white colonists to criticize a chief like Hintsa for not controlling his Xhosa. It was only his tribe, Gaeleka, over which he had authority.

Old Grandmother as real power is nice story-telling, and there could always be exceptions to the rule but this is totally against tribal tradition. For her to bring up question of boys` circumcision is just unheard of.

Postulating that the southward movement was aligned in the main to a reassignment of land upon death of headman is a reference to a rare occurrence. Headship of the ibandla (homestead) was inherited; the diffusive nature of groups stemmed from several factors.

The circumcision ceremony appears to follow the more rigid Sotho/Tswana form. Nguni were less dramatic, and organizer was not 'induna' i.e. witchdoctor. Mangope's (the name is Sotho-Tswana not Xhosa) dismissal of the whole rite (p48) is out of line. To this day, even in the cities, a young Xhosa man - like a young Jew - would consider it unthinkable that this ceremony be avoided. Pauw has excellent notes on current methods,

When Adriaan and Dikkop take off north, it would be impossible to "encounter not a single human being in the first 11 months". The land was inhabited - from 300 AD as we have seen in Zimbabwe chapter - and now extensively by Sotho, Tswana, Venda, Pedi etc. "In the 12th month they come across a pathetic group fleeing some enemy to the south" - A confusing situation since this presages the Mfecane.

The first clashes between Boer and Xhosa need discussion. There may be some danger in oversimplification. First provocations came from both sides. The attack here is placed at hands of Xhosa. Spilhaus and Muller offer a different story with reference to unauthorized commandos smashing into Xhosa lands. Overall picture of struggle over pasture lends is correct, but need to consider some of published material on this first 'Kaffir War'.

Lodevicus remarking on no predikant and not knowing what to do etc. raises, again, earlier comment about total lack of contact, trade or otherwise, with the Cape or the drosdies of Swellendam, Graaff Reinet (1786) etc. Rooi Valck may be in that renegade category, Buys-type but Lodevicus, with all that's gone before?

References like "No one had ever heard of the American Revolution" are stretching it a bit: The revolts of Graaff Reinet and Swellendam were mainly attributed to its influence. Spilhaus gives, for instance, detailed descriptions of the rights of man, the resistance to compagnie 'taxation' the Voice of the People - as reflected in the Patriot Movement by men from the Eastern Frontier.

The conclusions need careful analysis. There need be no deduction from the potential strength of the statements and I won't detail my comments on the text here but areas give probl

Immigration: Several sources indicate that the Lords XVII's "reluctance" was not that deep: In 1716 the XVII submitted searching questions to the Cape Government as to whether more white immigrants could be absorbed. The answers of the Cape Government were discouraging. See Oxford History, p 201: "These strong opinions against white immigration decided the Directors to allow the Cape to continue importing slaves. In this sense, 1717 was a turning point in South African history." Scholtz, p 25: "In 1750 the Cape government asked local boards to consider white immigrants. All agreed it was "absolutely impossible' - limited markets, capital and skills inadequate, slow transport, wide dispersal of population constricted trade.

Indirectly, the restricted trade contributed to problem but there seems to be local anti-immigration policy - because they did not want their share cut down? When the British took over, the same land was suddenly able to take 5000 immigrants, and 20 years later, 2000 and so on.

Education and culture: The Kerkeraad (Church council) had direction in first instance of education. Problems here with "predikants were afraid that Cape Town schools might arise with alien ideas." Refer to my detailed reports on the problems especially the fact that the 16,000 settlers in 1795 were spread out over 136000 square miles. Finally, the debate on make-up of the population should be resolved: In specific, the majority contribution of the German immigrants as indicated by so many sources.

Sources:

Swart Suid Afrika - Scholtz.

Oxford History of South Africa - Wilson/Thompson.

South Africa - Monica Cole

500 Years of SA History - Muller

The Cape of Good Hope - Pearse

The Xhosa - Alice Mertens

South Africa Official Yearbook 1974

First Europeans - Delagoa Bay - Punt

The Second Generation - Pauw

Die Afrikaanse Volkskultuur - Abel Coetzee

Travels in Southern Africa - Lichenstein

Bantu Speaking Tribes - Schapera

Khoisan Peoples - Schapera

Geography of the British Colonies - Lucas

Illustrated Social History - Hattersley

The Afrikaner as viewed by the English - Streek

Masters of the Castle - Picard

Peoples of Southern Africa - Tyrell

Illustrated Guide to Southern Africa - Reader's Digest

The Right to the Land - Davenport and Hunt

Education in SA - Malherbe

A History of Graaff Reinet - Wyndham Smith

Afrikaans and Malay-Portuguese - Valkhoff

Standard Encyclopedia of South Africa

African Societies in SA - Thompson

SA in the Making - M. Whiting Spilhaus

Various Photocopies. Gordon/ Hunting/ Graaff Reinet etc.