James A. Michener, one of America’s best-loved authors, won the Pulitzer Prize. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor. His books topped the New York Times best-seller list. Michener was at the peak of his career, when he took the ideas and words of a young immigrant from South Africa and told the world they were his own.

I was that young South African. I worked with Michener for two years from 1978 to 1980, a collaboration that produced The Covenant. I plotted the book with Michener, I did the major research, and I wrote thousands of words for key sections of the novel.

These archives contain examples of my original handwritten drafts that Michener retyped and pasted into his manuscript, my plot lines and character sketches. The items in these pages range from the profound to the seemingly trivial as with names of characters derived from my personal circle of friends.

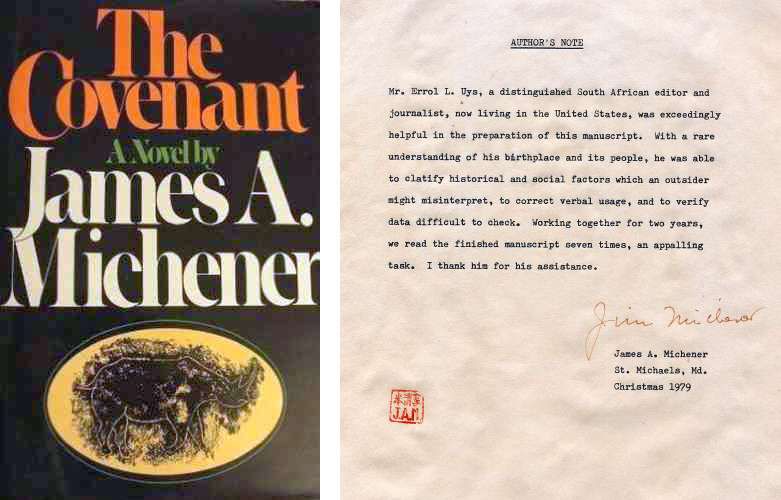

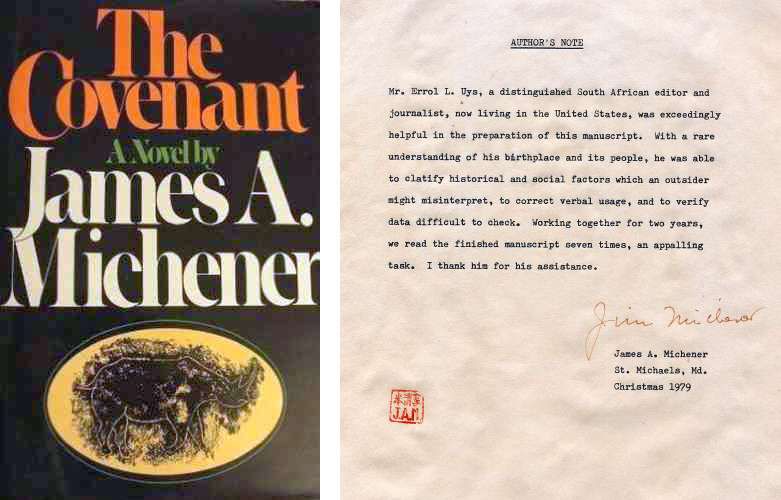

When our work was completed, Michener penned an author's note for his book in which he wrote:". . . Working together for two years, we read the finished manuscript seven times, an appalling task. I thank him for his assistance."

As these pages show, my contribution to The Covenant went far beyond an exhaustive reading and revision of a finished manuscript.

In an age of zero tolerance for purloined words, I marvel at statements by Michener that he came to see as gospel: “I write every word of my books;” “I do all the research myself;” “One of the saddest aspects of my writing is that I have never come upon any young person of obvious talent whom I might have helped to a professional career.”

The story of my collaboration with Michener is discussed in a chapter of Stephen J. May’s biography, Michener: A Writer’s Journey.

“Michener committed a scarlet literary crime and used his celebrated status in publishing to get away with it, ” concludes Stephen May.

-- Errol Lincoln Uys

*The full Covenant manuscript collection is held at the University of Northern Colorado, Greeley

On a fall morning in 1979, I sat dreaming beside Broad Creek near St. Michaels on Chesapeake Bay. A pair of white swans drifted in and out of my line of vision. In my mind's eye I saw a young girl walk to a pool where ranks of ghostly warriors rose from the waters. Some were black like the child's people; some specters were white and ashen-faced.

The scene I pictured took place far from the shores of Maryland. The girl's name was Nongqause and her people were the Xhosa of South Africa. The pool visited by Nongqause on a morning in May 1856 was on a tributary of the Great Fish River that marked the Eastern Frontier of the Cape Colony, where for a century the Xhosa resisted the incursion of Dutch and English settlers.

Nongqause fled the apparition, a pied hornbill's roars filling the forest behind her. She ran to the hut of her uncle, Mhlakaza, a seer who read the bones.

"I s-saw more warriors than I can count."

"Coming here?"

"No, uncle. Warriors in the mists."

Mhlakaza listened intently as Nongqause described her vision, and then spoke gently to his niece. "Return to your family but tell no one of what you saw."

Two days and two nights, the seer sat in his hut, burning pots of herbs and chanting to his sacred patrons. On the third day, Mhlakaza picked up an assegai and walked to the cattle kraal. He chose the finest animal from his own herd, slashed its hide and made the blood run. Through the bellows of the dying beast, the spirits let their commands be known.

At first light on the fourth day, Mhlakaza went to the pool. A brother who died fighting the Redcoats was in the front row of ghost-warriors. White soldiers stood shoulder to shoulder with the Xhosa.

Nongquase"We've chosen Nongqause to be Voice of the Spirits. You, my brother, will guide the child."

Mhlakaza and his protégé traveled the lands of the Xhosa carrying word of a ghostly legion coming to take the field against the settlers. The white allies of the Xhosa were Russians from the Crimea, enemies of the English.

Nongqause revealed what must be done on the day of deliverance: "Kill your cattle, every beast in every kraal. Empty your grain baskets and burn every field."

The peace on Broad Creek, the drifting swans - nothing lay further from the horror I saw unfold in the valleys of the Xhosa.

No Xhosa regiments streamed over the frontier, no Russian gun carriages trundled across the veld.

The time of starving began. Hundreds of bodies lay in fields of bleached bones. At distant kraals, fires were lit and pots brought to boil for the flesh of humans.

Fifty thousand Xhosa perished in the national suicide. Mhlakaza died of hunger. Nongqause lived until 1898. She never forgot holding the Xhosa in thrall. She told her coterie to call her Victoria Regina.

I left the dock on Broad Creek and walked up to a modest white cottage. I opened the door to the front porch and let myself in quietly. The room was bright and airy and furnished with a worktable where I spent most of my days in the fall of 1979. The view of the creek was idyllic, more enchanting when flights of Canada geese patterned the sky. Flocks of raucous, honking birds dropped down to the marshes. Some bands landed on the lawn below the cottage, where pickings were few and disappointing and the geese had a way of showing their disgust.

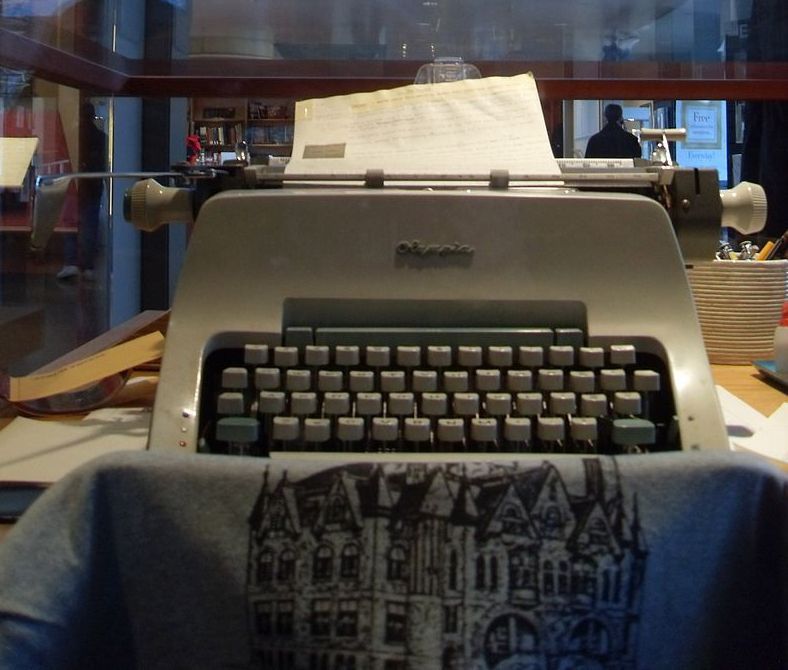

I sat in front of my typewriter, my back to the windows overlooking the glories of Chesapeake Bay. There were moments when I enjoyed the passage of the birds and the lovely sunsets but such reveries were rare. I was working twelve to fifteen-hour days to meet a fast-approaching deadline.

I took three pages from a manuscript on the table. The heading - "XI. The Englishmen" - appeared on the first page. In the third paragraph stood a reference to Nongqause: "a short, frail girl of fourteen went to a pool in a stream east of the Great Fish River and saw ghosts who spoke with her." What followed was a shallow telling of the story that had Mhlakaza plotting to make himself paramount chief of the Xhosa, identifying the white specters as Russians from 'newspaper clippings' and needing just over a month to scour "Xhosaland" and hoodwink an entire nation.

I drew a line through the manuscript and started from scratch. I began my first draft by hand on the back of the rejected pages. Sometimes when a stream of ideas comes, I dash them off in an ungodly scrawl. On this occasion I printed every word in carefully spaced lines and edited my writing in the same neat hand. Looking over the pages today, the meticulous penmanship is striking. Was it a burden of enormous tragedy evoking the reverential?

I later knew the same awe when writing about an apocalypse in the backlands of Brazil, where the prophet Anthony the Counselor promised paradise and delivered his followers to perdition. You imagine yourself in the shoes of the faithful and join thousands of believers who rejoice in a new life beckoning them. You lift your pen and move on. They remain behind forever.

I sat alone on the porch but as I worked I heard another typewriter. Tap-tap, tap, tap, tap. When I was pecking away furiously with two fingers - Fifteen years in editorial offices, I'd yet to master touch-typing and never would. - I ignored the clacking sounds. Tap-tap, tap, tap, tap. Sometimes I was goaded to type faster and faster, slamming back the return carriage. There would be moments when I paused to mull over ideas. Tap-tap, tap, tap, tap. If I let the noise in, I would picture the man at the other machine and wonder what he was working on.

On that day in November 1979, I finished my draft and made some final corrections. Satisfied I'd caught the tragedy of the Xhosa, I picked up the pages and went to offer them to the man behind the other typewriter.

The room Michener worked in was just off a small dining room. The smaller of the cottage's two bedrooms, it had been turned into a study. A heavy oak desk was placed next to the only window, standing sideways in the narrow space. The room was at the back of the house, the view from the window offering few distractions. Loblolly pines lined a long gravel driveway from a road where the little traffic passed unseen and unheard. Bookshelves covered one wall of the room, other volumes stood stacked on the floor. A stereo player and pile of records occupied one shelf. The room was not bright, usually only a single desk lamp turned on beside the typewriter, an old, heavy and noisy manual.

Its owner had stopped typing, the door slightly ajar. I pushed it open slowly to ensure I wasn't intruding. No, it was OK to go in, and I did, stepping quickly over to the desk.

I can see him now, sitting in the shadows cast by the single lamp. He was wearing a red plaid shirt that hung loosely over a baggy pair of khaki trousers. His shoulders were slightly sloped. His hair was thinning and receded far back from a high forehead. His mouth was small and thin-lipped. He had large hands with long fingers, expressive of strength rather than sensitivity.

On that day in November 1979, I finished my draft and made some final corrections. Satisfied I'd caught the tragedy of the Xhosa, I picked up the pages and went to offer them to the man behind the other typewriter.

The room Michener worked in was just off a small dining room. The smaller of the cottage's two bedrooms, it had been turned into a study. A heavy oak desk was placed next to the only window, standing sideways in the narrow space. The room was at the back of the house, the view from the window offering few distractions. Loblolly pines lined a long gravel driveway from a road where the little traffic passed unseen and unheard. Bookshelves covered one wall of the room, other volumes stood stacked on the floor. A stereo player and pile of records occupied one shelf. The room was not bright, usually only a single desk lamp turned on beside the typewriter, an old and noisy manual.

Its owner had stopped typing, the door slightly ajar. I pushed it open slowly to ensure I wasn't intruding. No, it was OK to go in, and I did, stepping quickly over to the desk.

I can see him now, sitting in the shadows cast by the single lamp. He was wearing a red plaid shirt that hung loosely over a baggy pair of khaki trousers. His shoulders were slightly sloped. His hair was thinning and receded far back from a high forehead. His mouth was small and thin-lipped. He had large hands with long fingers, expressive of strength rather than sensitivity.

His eyes were his strongest and most enigmatic feature. They were eyes that literally gazed out across the world, for with the exception of Antarctica, there was no continent he hadn't visited. (Later he added the ice-bound south to his wanderings.) His gaze was sphinx-like, seeing everything, revealing nothing. I saw rare merriment, melancholy sometimes and secrecy often. Some moments I glimpsed a sharp, calculating look, like an old lion sizing up a young male in the pride.

I handed over the story of Nongqause and Mhlakaza. "A Xhosa Jim Jones without the Kool-Aid." The mass suicide of Jones and his followers took place in Guyana the previous November.

My quip went ignored. "Let's see what we have," James A. Michener said.