My library forays in New York over three months in 1981 provided the background for my initial plotting and book proposal. With the outline complete and broad themes of the novel well in mind, it was essential to have firsthand experience of Portugal and Brazil. I couldn't go back five hundred years, but I could make a sincere and honest attempt to know the land and its people.

I was writing a novel not a history but was committed to offering as authentic and historically accurate account as possible. In April 1981, I headed for Lisbon and three months later began my journey in Brazil.

I based myself outside Lisbon at Sintra, living in a quinta on a hillside below Moorish battlements that overlooked Sintra Palace. I would use this setting for the family seat of the first Cavalcantis to go to Brazil.

Through his marriage to Inez Gonçalves, Cavalcanti's father had come to possess lands on those serene vales before the Serra de Sintra. Here between jagged rocks of antiquity crowned with fallen battlement of Moor and the distant azure expanse of the Atlantic, here was past and future, and whether Nicolau climbed through the thick woods to the lee of the old Infidel redoubt or stood on the windy headland at Cabo da Roça, he felt an intimacy with both.

I divided my time between the Gulbenkian Foundation, British Institute and Portuguese historic and geographic libraries and visits to sites like Jeronimos Monastery, Belem Tower, Mafra, and traveling to Coimbra, Belmont and Evora, all of which have a place in my novel. Besides 16th century Portugal, I was also interested in the mid-18th century and events surrounding the Lisbon earthquake of November 1755, one of my Cavalcantis studying law in Portugal at the time.

Ten seconds later, there was a devastating shock. The houses opposite Paulo began to sway; the floor beneath him vibrated so violently that he struggled to keep his balance. Chimneys crumbled, loose tiles fell to the ground, crockery in Dona Clara's house shattered. Screams and the pitiful cries of animals rose. But Paulo's perception of these noises was dulled by a thundering in the earth. Terremoto! The word crashed through Paulo's senses. “Earthquake!”

Paulo was mesmerized by the houses opposite, rocking on their foundations, walls cracking and splitting, upper stories leaning toward the street, chunks of masonry falling. Terror numbed him. He stood frozen at the window, expecting death.

Three houses suddenly burst open and collapsed, burying the family of four and the servant girls. The old man did not cease his struggle to open his front door, even as the convulsions rocked the street; he, too, was entombed by an avalanche of masonry. Paulo looked beyond the opening opposite him: The city was rising and falling in waves as if upon a storm-tossed sea; landslides swept down the hillsides hurling houses toward the lower ground; distant steeples and towers whipped about wildly; clouds of dirt and dust hung in the air. The thunder of the earth, the sound of breaking timbers, the rain of roof tiles — the inconceivable noises came together in one deafening roar of destruction.

Before leaving Portugal for Brazil in July 1981, I prepared a list of research objectives sent in advance to potential contacts in Brazil's cultural and educational ministries, historians and others whose names had been suggested by sources I'd met in Portugal:

My novel is historical and a major part of my work can be accomplished through a study of published sources. No matter how assiduously this is undertaken, such bookwork cannot offer on location observation with its inestimable value in bringing comprehension and adding reality to your perspective. The following notes, more or less in line with my envisaged chapter structure, indicate the kind of material and experience I am seeking.

Creative people are not supposed to be as formal as this, but with so vast a project in mind I have to adopt some kind of organized strategy for the research stage or I'll never put it all together.

Historical fiction research plan:

I want to describe, in detail, a single acre — "God's Little Acre," in a way — before mankind's arrival. I need to speak with experts at a forest research station (outside Belém?), who can explain, in simplest terms, the symbiosis of the forest, its creation and the miraculous web of life that ensures its survival. I need a geologist to outline the creation of the Amazon basin and the forces that shaped the sub-continent as we know it today. A zoologist to tell me about the animal life of the virgin forest. And a sociologist who can expound on "man and the forest," the forest's effect on man over the centuries, both indigenous and immigrant. (Charles Wagley, An Introduction to Brazil, has some pertinent remarks on this theme.)

I'm keen to keep the forest in perspective, but do see it as an important link to a non-Brazilian's understanding of the country. The perspective a Brazilian would like to see should come to a reader of a book such as mine as the full extent of Brazil's story unfolds. It will become clear that the cliche image of jungle and river and little else is erroneous.

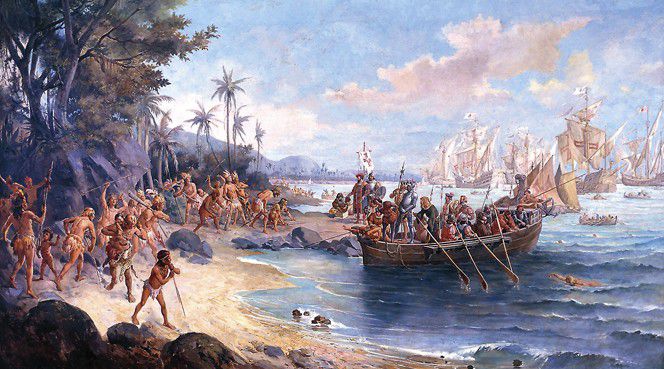

I am aware that visits to Indian groups are difficult to arrange and my feeling is that while observation of an Amerindian settlement would be valuable, I can sympathize with serious-minded anthropologists having to contend with 'visitors'. Again, there is a wealth of published material on Indian culture and I'm capable of drawing my inspiration from this. However, it would be valuable to talk with an expert on the Tupinamba and Tupiniquin groups in the vicinity of the littoral at the time of Cabral's landfall. And to visit a worthwhile museum or other institute that exhibits their artifacts and depicts their lifestyle.

I have well in mind a story built around the main group that Cabral encounters and the gaps in my knowledge are the kind that can be filled during some intensive sessions with someone who knows the early history and has a sympathy for the first inhabitants of Brazil. On Cabral's landfall, I would like to visit Porto Seguro and environs, possibly get out to sea on a boat and imagine the rest for myself.

What I also find of great value in trying to recapture these early historical stages are collections of old prints, etchings etc. That solitary, forgotten artist can often bring more lucidity than a pile of text!

Seen in the first quarter of the 16th century, this section has been researched in Lisbon and emphasizes the Portuguese empire in the East and early attempts at settling Brazil.

However, it is here that I show the first of my two major fictional families — the Cavalcantis in the captaincy of Duarte Coelho in Pernambuco.This leads to one of my most crucial research projects: The Cavalcanti sugar plantation, (near Olinda?) is seen throughout my book, from 1534 to the present, from initial pioneer tract to "Big House" of the 18th century, to usina, and to independent plantation of the 1970's successfully thwarting a multinational agribusiness takeover bid.

I am interested in every aspect of such a plantation from the simplest detail such as how sugar grows to the social life and values of the plantation itself and its relationship with the surrounding community. I'd look for details as prosaic as the equipment in an 18th century kitchen, the schooling of the owner's children, local festivals, customs etc.

I have, of course, read Gilberto Freyre's works, and anything else I have been able to lay my hands on but this cannot replace an opportunity of visiting a plantation and gaining a real insight into its past and present.

It will be essential for me to meet with Jesuit historians to talk about the early history of the Company in Brazil and get a clear picture of their relations with the Indians and settlers. If anything remotely like a reduction — present day mission station? — exists, I would like to visit it. But I am more interested here in "matters of the soul;" I have a great feeling for those early preachers engaged on so daunting and lonely a mission in the New World and intend to devote a chapter to them.

I need to know what it was really like. What manner of men, what motivation brought the courage that led Nobrega and Anchieta to assume so formidable a task?

I would also like to have the settler opinion from a qualified source: the reaction to the fathers, the reductions etc. (For this and later sections a visit to the Missiones area, might be valuable.)Since I have always lived in a Protestant-orientated society, I would welcome meetings with Catholic churchmen on the importance of religious values in a society such as Brazil, in its formative and growth stages. I would like to comprehend the role and importance of the priest in a small community by observing rather than talking about it.

5. The Bandeirantes

I'll first deal with São Paulo through the early Paulista settlement and the Jesuit reduction; later, as home base for the bandeirantes. Here, Bernardo da Silva's clan, the second major fictional family of the book emerges and will be seen in conjunction with the Cavalcantis from this point onward. Besides the bandeirante era (I concentrate on 1628-1681,) subsequent chapters will see the da Silvas involved in the gold mines to the north and, finally, in the days of the Empire, established on a coffee fazenda. They later head up a large corporation in São Paulo interested in, among other things, road construction in Amazonia.

As with the sugar plantation, I need to spend a brief but intensive period on a classic coffee fazenda.

On my draft itinerary I have in mind a visit to the headwaters of the São Francisco/Doce rivers, the area roamed over so many years by Fernao Dias Paes Leme, on whom I lean strongly for characterization of my bandeirante patriarch.

With the bandeirantes, I specially want to get a picture of their lifestyle that goes beyond the much-publicized bandeiras — family life, day-to-day existence, community structure, relationship with authority, 'peaceful' pursuits of work, industry etc.I'll be writing about one of the greatest bandeiras of all, that of Raposo Tavares from São Paulo to the Madeira and Amazon. I obviously don't plan to follow his exact route but will pick up glimpses of it through travel and research for other sections of the book.

6. The Planters

The Cavalcanti sugar plantation is seen over four centuries and requires detailed research. Here, too, I'm interested in the slave market at Recife; the arrival, sale and life of the slaves.

For this section, I want to visit the backlands of the northeast, the classic sertão. I'll also need to have touched base with Ouro Preto, and the mining era museums etc. Bahia (Salvador) is seen briefly, with particular reference to the Jesuits and the Misericordia.As my research priorities indicate I am, in the main, staying away from major cities. The localities I'm interested in offer an attainable framework for a non-Brazilian writer: to attempt anything in detail about the big cities is asking for trouble. There will, of course, be brief forays toward them as with Carnival in Rio.

7. Empire

The da Silva fazenda looms large during this period - a fazenda prosperous enough to have Emperor Dom Pedro II pay a visit to it.

Two major research areas here are the Paraguayan War and the Abolition of Slavery. As I stress throughout these notes, while some of my time can be given over to interviews I plan this as a field trip - It will be better for me to visit some of the battle sites of the war with an enthusiastic military historian than to examine uniforms, weapons of the era in a museum.

8. Foreigners and Fanatics

For this section, I need to visit the site of Canudos. I've read Euclides da Cunha several times, as well as other references to this tragic episode but beyond the "facts," it is important for me to simply walk the ground upon which Conselheiro and his people fought and died. Perhaps to seek out backlands villages untouched by time that are reminiscent of the era.

My next interest lies in the Madeira-Mamoré railroad. A brief visit to Manaus could profitably be followed by a river trip down to Porto Velho and environs of the railroad project. Here, too, I want to deal with Roosevelt's 'River of Doubt' expedition. Clearly, time will not allow me much prospect of a close examination of the terrain traversed. More important will be knowledge of Colonel Rondon and the Indian Protection Service.

9. The Modern Era

Among my interests are the USAF base at Recife, Brasília, the Trans-Amazonia highway and a model private colonization scheme such as Alta Floresta near Aripuana. I want to get a proper understanding of developmental challenges in the Northeast, both historical and contemporary, and a contrasting view of the spectacular boom in São Paulo and its environs.

I have no preconceptions about how to approach the modern section of this novel save an underlying sense of optimism about Brazil and a willingness to listen and learn.

These notes give an indication of my broad research requirements on a field trip through Brazil.

Noticeably absent is any reference to emotive and spiritual values — the intangible "something" that will go toward an understanding of Brazil as a nation and Brazilians as a people. This can only come after many weeks of contact with Brazilians, from the impressions they leave and the suggestions they are more than likely to make to a stranger seeking to find out what is Brazil.

Besides these research objectives, I offered a glimpse of my story lines, enough to grasp my plans for the book and more specific research needs:

Notes on Research Project: Brazil — July to October, 1981

While I am aware that the role of the rain forest in Brazilian history should not be over-emphasized, I want to open the book with a succinct evocation of the life cycle of an acre of virgin rain forest; its creation and existence before the advent of mankind.

The first dwellers in the forest, the Indians, are seen in the period 1492-1500, eight years leading up to the arrival of Cabral's fleet. Emphasis is placed on the Tupi-Guarani branch and, in particular, a Tupinamba and a Tupiniquin group. While a novelistic technique carries the story forward, I am equally concerned with a sympathetic account of their lifestyle and its value-role in the formation of Brazilian society.

“After showing Cabral's landfall, my focus turns to the Portuguese trading empire in the East, stressing Goa and Ormuz, in the period 1506 — 1516 to give the reader a concept of the men who first settled Brazil and their heritage. With Cabral's fleet at Ormuz and Goa and, later, in the Pernambuco captaincy of Duarte Coelho, the 'novel' as opposed to the 'history' is advanced through the experience of members of the Cavalcanti family, one of two major fictional families who people my book. The first Brazilian episode is drawn against a background of pioneer settlement, sugar plantation, settler-Indian relations and Franco-Portuguese conflict along the coast.

“The arrival at Bahia (Salvador) in 1549 of Padre Inácio Cavalcanti in the company of Tomé de Sousa, first governor-general, opens the next epoch in Brazilian history. I deal with this through the Jesuit Cavalcanti, again, a fictional character though some might say he was inspired by the life of Anchieta. I see Inácio as a tragic visionary caught amid the conflicts that arise between those who seek the soul of the Indian and those who want his body.

“The historical setting for Inácio's story (1543 - 1586) encompasses the early missionary-Indian contacts, the controversy over Indian enslavement, the reductions. It also sees the advent of Bernardo da Silva, patriarch of the second major fictional family. Silva is a Paulista whose son, Amador, features as one of the great bandeirantes.

“This chapter which spans sixty years will portray the saga of the Brazilian pathfinders in much the same spirit as the trailblazing pioneers of the American West. I find the records of these backlands conquerors as stirring, if not more so, than their north American counterparts. Nothing I've thus far read, which attempts to place their story before the north American reader, does them justice. This, of course, does not excuse their excesses in their raids on the reductions but just as must be the case with other pioneering groups, there is a constant need to examine the bandeirantes within the limits of their own time and perspectives.

“The latter chapter, too, touches on the Dutch occupation of the northeast and the drawing together of various elements of the nascent Brazilian nation in their resistance to the invaders.

“While I appreciate that approaching the Brazilian story on a north-south axis has been somewhat overdone, there seems justification for repeating it this once more. Thus, I have the 'south', São Paulo, represented in the story of the Silva family and the 'north' with the Cavalcantis. Later sections of the book will bring into perspective the importance of the western lands, in a more appropriate end timely frame.

“After the formidable bandeirante saga, I want to follow a slower pace through the next chapter with 'The Planters,' the story of the Cavalcanti plantation and its people from 1720 - 1792. I am most concerned here with the developing social values, the question of slavery, the Pombal era, the stirrings of nationalism through the Tiradentes episode. For much of this section, the Cavalcanti estate is ably run by the widow, Dona Domitila Cavalcanti, an unusual figure in those days but one which will afford a special insight into the role of women in 18th century Brazil.

“I see value in using such contrasting personalities for underlining certain points, just as it is the Cavalcanti plantation priest, Father Viana, who reaches toward an understanding of the problems of over speculative agriculture.

“As the story of Brazil unfolds, my next chapter, spanning 1864 - 1889, moves to the prospering coffee fazenda of the Silva family near São Paulo. It rests on two major events: War of the Triple Alliance and the Abolition of Slavery. Both are seen against the backdrop of Brazil as an independent empire, with Dom Pedro II featuring throughout.

“Moving toward the present century, I tell the story of Vicente Cavalcanti, who is closely involved with three historical figures: Conselheiro, Rondon and Roosevelt. Shifting from the sertão the Amazon area, Vicente's saga covers Canudos, the Madeira-Mamoré railroad's construction, with asides on the rubber boom and the Rondon-Roosevelt 'River of Doubt' expedition by which time Vicente is a member of the Indian Protection Service.

“The period 1945-1975 will see the Cavalcanti-Silva families united in marriage and fortune, through incidents that unfolded during the days of the Empire. Major events to be used for this section include Brazil's little-known but important contribution to World War II with emphasis on the U.S. base at Recife; the fears of insurrection in the North-East in later decades, Brasília's birth, the development of the Trans-Amazonia highway. Through this section I intend to show the unity and diversity of Brazil, the tremendous challenges facing the second largest nation in the Western hemisphere, the search to define its relationship with the United States, the fears and hopes of its people.

“Conclusions, of course, can only lie at the end of a great deal of work and research and thought, but I envisage a final chapter of hope and celebration, written around the Rio Carnival and a model colonization scheme in the Amazon area.”

These gleanings from my outline and in-depth reading and research were intended to convince those whose help I sought that I was involved in a serious project of which I already had more than a working grasp. A breathtaking and formidable task but which, after my two years with Michener on The Covenant, I had every confidence of accomplishing.

I prepared a draft itinerary that would allow me to touch base with all the important locations in the novel, an itinerary clearly open to revision as priorities demanded.

Draft itinerary for visit to Brazil: July to October 1981

July 2 Arrive Recife from Lisbon

July 3 - 7 Recife/Olinda

July 8 - 12 Recife/Olinda area - "sugar plantation"

July 13 - 14 To Canudos - Pernambuco 'backlands' en route

July 15 - 16 Canudos

July 17 - 18 Salqueiro - Belém (surface)

July 19 - 21 Belém (Amazon forest research station etc.)

July 22 Belém - Manaus (air)

July 23 - 26 Manaus

July 27 - 29 Manaus - Porto Velho (Madeira River?)

July 20 - Aug 8 Porto Velho - Madeira-Mamore railroad/Aripuana to Alta Floresta/ Rio Roosevelt

Aug 9 Porto Velho - Brasilia (air)

Aug 10 - Aug 15 Brasília

Aug 16 - Aug 22 Brasília - Salvador via Sáo Francisco area

Aug 23 - Aug 29 Salvador

Aug 30 To Porto Seguro

Aug 31 - Sept l Porto Seguro - Ouro Preto

Sept 2 - 3 Ouro Preto

Sept 4 - 10 Rio de Janeiro (lst visit)

Sept 11 - 15 São Paulo

Sept 16 - 24 São Paulo ( on coffee fazenda)

Sept 21 São Paulo to Asuncion (air)

Sept 22 - 24 Asuncion, Paraguay

Sept 25 - Oct 3 Asuncion - Humaíta to Missiones area etc.

Oct 3 - Oct 17 Rio de Janeiro for consultations with local historians/contacts

Oct 18 Return to New York.

I was to begin my trip at Salvador, the Mother City, the best possible start to a journey in search of the “real Brazil,” as people in the south refer to Bahia. From Salvador I went to Porto Seguro and Cabrália, walking along the beaches and broad bluffs that are the setting for the opening of my book along the same beach where I saw the young Tupiniquin, Aruanã, at the water's edge on a day in 1500.

Tiny puffs of cloud had fallen to the end of the earth. Four... five...six were bunched together just above the horizon, and others were coming to join them. Otherwise the sky was perfectly clear, its blue expanse streaked with the blazing color of the lowering sun.

He made a hesitant progress toward the water, squinting into the distance at the strange clouds. But even as he did so and perplexed as he was, he began to see that his first impression had been wrong. Very quickly now the swiftest clouds lifted above the water and he saw a darker line. There was a flash of understanding: Here were great canoes coming from the end of the earth.

Aruanã watched as they came closer. The sun was gone behind the trees, and he found it difficult to discern the craft, but he stood rooted a while longer before he realized that he must hasten to the village and tell what he had seen. This made him gaze at the horizon again, to be absolutely certain, for it was a fantastic discovery for a man who had gone to seek no more than shells for First Child. They were there, darkening images now, these canoes that had come from the end of the earth.

From Porto Seguro to Brasília, a tremendous leap in time and imagination that was to prove fateful. Though I did not know it then, I was being handed one of the keys to my vision of Brazil, the metaphor of Brasília and E1 Dorado. In his review of Brazil , the eminent Brazilian literary scholar, Professor Wilson Martins wrote:

What we have in front of us is the Brazilian national epic in all its decisive episodes — the indigenous civilization and the El Dorado myth that they themselves created and supported, passing it on to the hallucinated imaginations of the conqueror; the discovery and domination of the North-East; the Bandeiras and geographical expansion; the gold rush and nationalist feeling present, not only in the struggle against the Dutch but also the Inconfidência Mineira; the Royal Family's arrival and the Independence; the Second Reign and the war with Paraguay; the Abolition and the Republic — everything converging like the segments of a rose window in that reborn and metamorphosed myth that is Brasília, symbol of the proclaimed territorial integrity and, not without reason, with the expeditions that expanded to the south and to the west on the pretext of capturing Indians and searching for the “Golden Fleece.”

From Brasília, I traveled to Piauí and the sertão of Bahia, to Uauá and Canudos. Like so many other stops along my journey, I was there to brood over the past. I already had the broad picture but needed the innumerable small details to fill my canvas. To have studied Euclides da Cunha's Rebellion in the Backlands and other sources was one thing, but go alone into the thorny caatingas, walk for hours with the sun burning down on you, rest upon that stony earth, not a little fearful that you're totally lost — it takes little to imagine the hell of Antonio Conselheiro's New Jerusalem.

My next halt was at Recife and Olinda where I spent three weeks, mostly under the guidance of Gilberto Freyre's Joaquim Nabuco Foundation. With their help I found my valley of Santo Tomás and my imaginary town of Rosário, the locales for my fictitious family of Cavalcantis.

From Recife I traveled to Belém and embarked upon the Amazon, five days of brooding along the river sea to Manaus and on to Porto Velho. What I had in mind in journeying the wilderness was not so much Nature's glories but the men who were first to venture there: the bandeirantes. Nowhere but in those lonely tracts of forest could I get a sense of the enormity of their undertakings, their indefatigable spirit and courage.

From Porto Velho and Cuiabá, I headed south to Rio, São Paulo and Minas Gerais. After so many weeks it was a shock, traveling out of the backlands to the great cities. I was as bewildered and lonely as the sertanejo who goes south, but even as I felt this I knew my intuition to start my journey in the north had been right. Had I plunged into Rio or São Paulo at the start, I could've been drowned but up north I was able to absorb the Brazilian "thing" in small doses, day by day.

This is a very real problem in developing a book like mine, for in so short a time no outsider can possibly hope to get more than a superficial look at a great city like Rio de Janeiro. Which is why when I got down to writing Brazil I placed my two families beyond the cities, the Cavalcantis on Engenho Santo Tomás near Rosário and the da Silvas of bandeirante ancestry at the fictional Itatinga on the Rio Tietê, their worlds a microcosm of the greater Brazil beyond.

More than the land, the Brazilian people themselves gave me the thousand and one insights I needed. Try to imagine a stranger coming to you and telling you he is going to write a novel about the entire history of Brazil. Five hundred years! A crackpot! Louco!Bemused some were but with one solitary exception, a fiery young man of Manaus who flew into a rage and said an estrangeiro had no right to "steal Brazil's past,” save for this lone objector, I'd unstinting help and support from hundreds of people, some giving me days of their time, some only precious moments. An unnamed peasant woman standing next to me in a bus queue in Brasília and asking that I buy an orange for her sick child: I realized later that the orange was all the pair had for nourishment on a twenty-six hour bus trip.

I kept my daily journal during my trip and filled twenty notebooks. I pored over dozens of maps, paintings, photographs, absorbing and interpreting this mass of information as I went along. I was not bound by the same constraints as the historian, my book is a work of the imagination, but I was under an obligation to get the facts right. Foremost was an overriding desire to write a book that was accurate, balanced and avoided stereotypical images and over-simplifications that often mar the works of outsiders attempting popular fiction about Latin America.

Where my interpretations revise commonly-held views, I arrived at my conclusions only after the most critical thought. My view of Brazilian slavery, for example, particularly the early centuries is harsher than what was usually portrayed.

I did not study Brazilian slavery in isolation but looked at the Portuguese record in Mozambique and Angola, particularly the degradation of the Congo; the more I thought about it, the less I believed that the harsh Portuguese slaver in Africa could miraculously be transformed into a paragon in Santa Cruz. Palmares was the quilombo that made "headlines,” but how many others were there? Tens of thousands of runaway slaves do not suggest a benign regime of bondage.

I asked myself time and again, and not only with slavery: through whose eyes was the past beheld? Almost never in a colonial situation does one find anything but the official story neatly penned for bureaucrats thousands of miles away.

I'm no “frock coat” devoted to the literary salon. I do not write staring above the heads of the mass of people. I like to get my hands dirty “to recreate history,” as one reviewer of Brasil said, “almost entirely at ground level.”

While generations of fictitious Cavalcantis and Silvas populate my landscape, I took great pains to bring to center stage a host of characters drawn from the masses. Affonso Ribeiro and his wild clan; Nhungaza of Palmares and his grandson, Black Peter; Antonio Paciência, the mulatto, slave, voluntário in the Paraguayan War, so-called "fanatic" at Canudos, above all, “Antonio Paciencia-Brasileiro!” A few of the many as dear and vital to me as the great men of the earth in Brazil, past and present.