Johanna, or "Joey, was born in Vereeniging, Transvaal in July 1892. Her mother died from injuries sustained in a train crash in 1896, and Joey went to live with an uncle and aunt, Michiel and Elizabeth "Lettie" Roux of Bethulie in the Orange Free State.

The Second Anglo-Boer War broke out in October 1899. In March 1900, British troops advanced on Bethulie to capture a strategic bridge over the Orange River. With Michiel away on commando, Lettie, her children Johann Petrus and Michiel Christoffel, and Johanna fled Bethulie with a convoy attacked by the British "Tommies" near Reddersburg in the Free State.

We trekked with fourteen wagons, seventy women and children, escorted by thirty Boer commandos. Three days after leaving Bethulie, the Tommies found us.

"O, God, ons is nou gevang!" - ("O, God, now we're caught!")

It was daylight. I hid under a wagon. Johann and the baby, Michiel, lay on the wagon floor. They could not understand what was happening. There was confusion. People screaming. Shouts. "Rooinek vark!" - ("Redneck pig!")

Women were shooting and killing Tommies. Tant Lettie was a crack-shot. She kept firing till she had no more bullets.

Three Boers died. We ran out of ammunition. We surrendered with a white flag on a stick.

I still see the red faces of the Tommies. They wore khaki, brass buttons, and leggings. Their heavy boots thudded as they walked.

They gathered our men together and took their guns and horses.

At the wagons, the Tommies searched the women and went through their belongings. The soldiers were not cruel. They had not tasted real war yet.

When they searched our stuff, my aunt sat on a trommeltjie filled with bottles of Lennon's home remedies. The Tommy's never looked inside the medicine chest. Tant Lettie had hidden gold sovereigns under the bottles.

After they took the men away, they made us get back into the wagons. We trekked across the veld to a station. We stayed there all night, those who could lying down, others sitting up in the wagons. In the morning, they pushed us into boxcars. I couldn't see anything. There were vents on top and one of these slammed onto my aunt's head. When the train moved off, the boxcar shook so much we fell against each other.

Before he left for commando, my uncle Michiel had looked at me. "Never desert her," he said to Tant Lettie. "If you've one crust of bread, break it in half and give it to her."

We realized we were going to Bloemfontein.

"You'll get food, everything you need in the camp," the Tommies said.

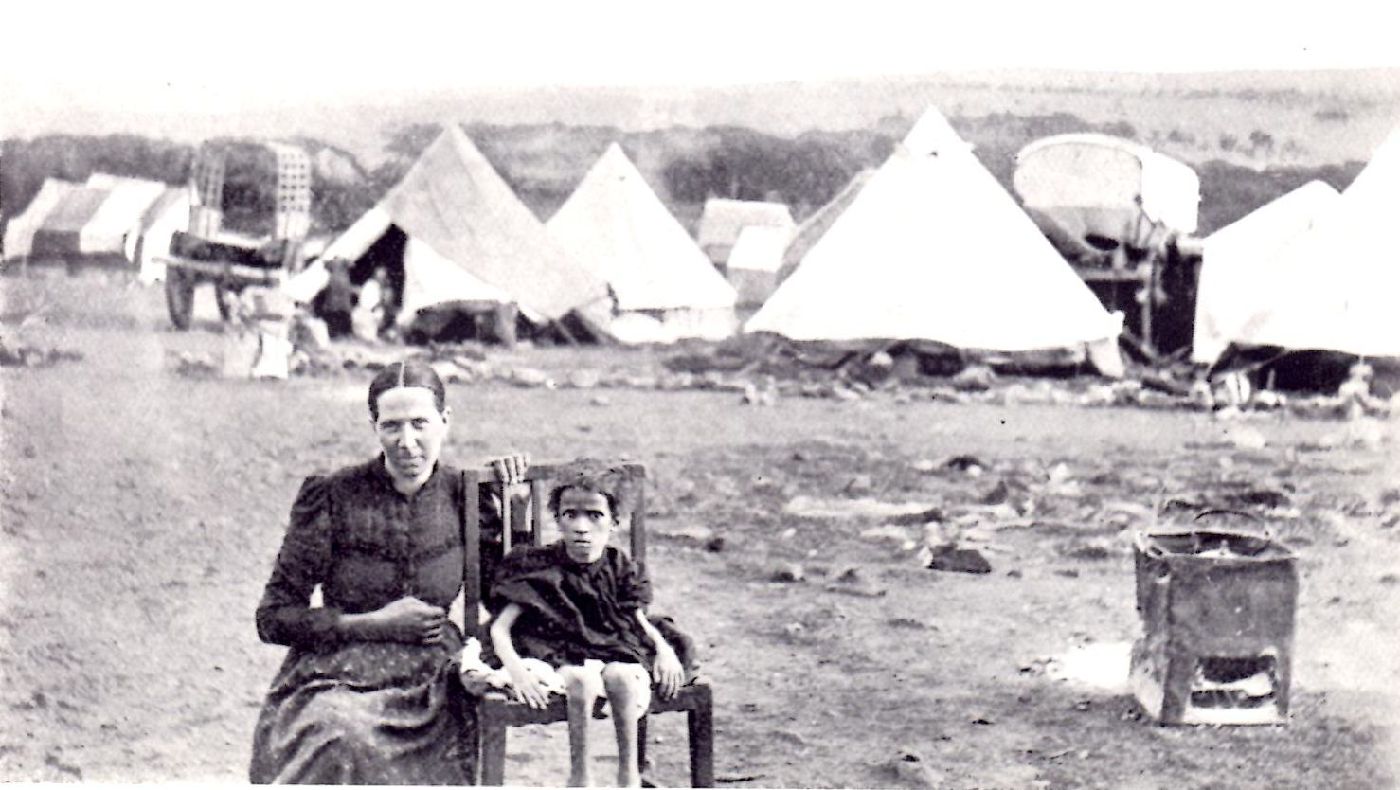

At Bloemfontein, they placed us in carts, took us three miles outside town and dumped us down on the veld.

They put up bell-tents for us, one next to the other. Hundreds of round tents, far as the eye could see. We met one of Tant Lettie's sisters and stayed together for a while.

A woman in the tent next to us went into labor. Her baby was born that night. The child died soon after.

We slept on the bare ground. No bedding, no pillows, only blankets from the wagon. It rained heavily. In the beginning, we did not know we had to loosen the tent ropes in a storm. We got sopping wet. Tant Lettie and I went outside in the rain. We released the ropes and knocked in the pegs again. It was a quagmire. Exhausted, we lay down in the mud to sleep.

We lit a paraffin lamp in the tent at night. At nine o'clock, all lights had to be out. Guards kicked and beat women if they disobeyed their orders. We obeyed.

We were issued ration cards and stood in line for food. We got meat, sugar, mealie meal, condensed milk. The meat was chilled. Even after cooking, it had chunks of ice in it.

We used a paraffin tin outside the tent for a stove with holes in the sides and irons to hold pots. We collected firewood on a kopje next to the camp. Water was brought from a river by cart. Every morning we stood in line to fill our buckets. We were always short of water.

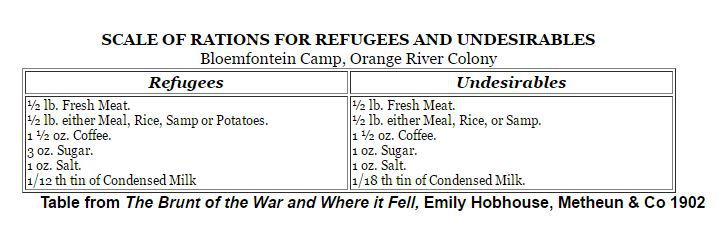

Tant Lettie, the two boys and Johanna were"Undesirables," a term applied to Boers who don't go voluntarily into captivity or had family members on commando. "Refugees" described displaced Boers who surrender, the "hands-uppers" and their dependents. The latter received a few extra spoonfuls of sugar, condensed milk, and the luxury of the occasional potato. In either case, rations are insufficient to stave off starvation and disease.

Michiel surrendered at Fouriesburg in July 1900. He was sent as POW to Diyatawala, Sri Lanka, where five thousand Boer guerillas were interned during the war. The British shipped four times that number to other camps in India, St. Helena, and Bermuda.

As Joey recounted the attack on the wagons to me, she sang a line of an old Boer War song: "Zij geniet die blouwe bergen op die skepe na Ceylon." — "They enjoy the blue mountains on the ships to Ceylon."

Michiel Roux contracted typhoid and died at Diyatalawa in November 1900.

If we had grievances, we were taken in front of the camp commandant. Usually, we kept quiet. We did not want trouble with the Tommies.

During the day, the women visited each other. We walked around the camp. The sun burnt us black. Our shoes wore out. Our clothes were filthy. Afterwards we got blue soap to wash our things. The toilet was horrible. A big hole with plank seats and sacking around it, you climbed up on top of the planks. No newspaper, no rags.

The camp was lice infested. I watched Tommies take their leggings off, unwinding them like strips of bandages. They used broken glass to scrape the lice from their legs. My aunt had to cut all my hair off.

There was a church, but I do not remember going to it or to a school begun in the camp. Tant Lettie read to us from the Bible.

Theft was rife. There were fights between women.

Prostitutes slept with both Tommies and Boers. One old man called De Wet was a bastard. He wanted to interfere with my aunt. She chased him out of the tent. Tommies also interfered with the women.

I remember a short man with a gray beard. I hated him.

My aunt became friendly with one of the Tommies. She stole someone else's skirt and walked with him.

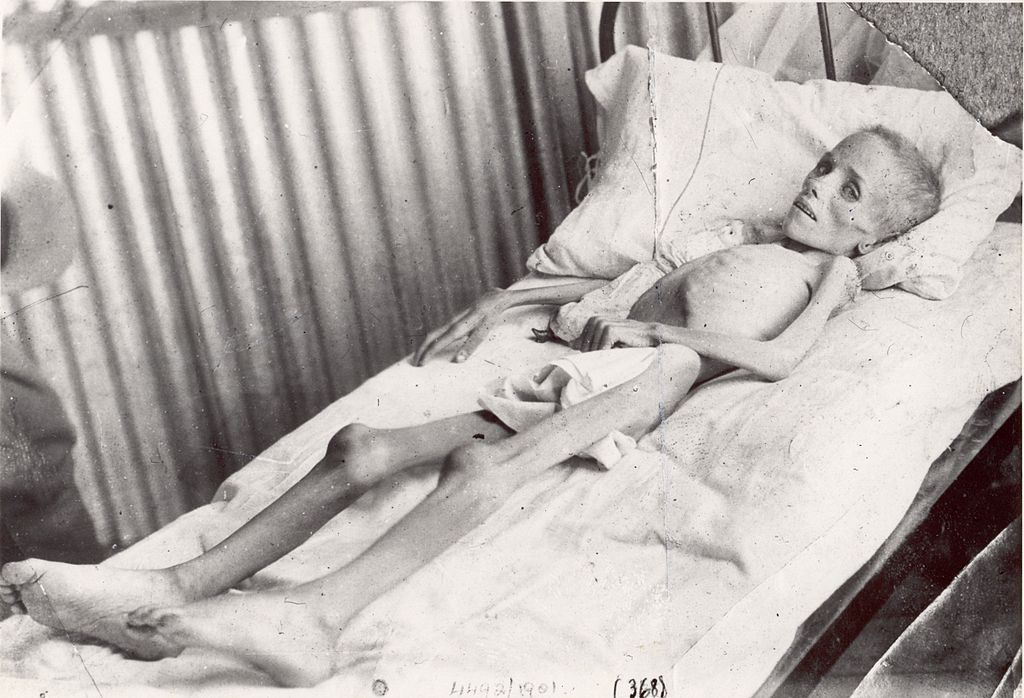

Thousands of newcomers arrived at the camp. Hundreds became sick. The marquee hospital tents were always full. The doctors worked day and night.

People died like rats. Carts came down the rows of tents to pick up the dead. There were funerals every day.

Emily Hobhouse returned to England to campaign against "a gigantic and grievous blunder caused not by uncaring women but crass male ignorance, helplessness and muddling." Her militancy brought the scorn of the British people who called her a rebel, a liar, an enemy of the nation, hysterical and worse.

No one hated Emily more than Lord Kitchener, whose troops burnt down 30,000 farmhouses, torched a score of towns and interned 116,572 Boers, a quarter of the population.

"It is for their protection against the Kaffirs," said the British War Secretary, oblivious to the fact that the English armed Africans against a mutual enemy. Also ignoring the fact that 115,000 "black Boers" were sent to their own concentration camps; twelve thousand of these loyal servants perished.

Authorities refused premission for Miss Hobhouse to inspect the most terrible of all camps: Bethulie, where Johanna and her family were interned from August 1901 until May 1902.

The concentration camps claimed the lives of 27,972 Boers. Of these, 22,074 were children like Lizzie van Zyl.

We guarded the gold sovereigns day and night. After lights out, we slept next to the box where Tant Lettie had hidden the coins.

Women could apply to the camp commandant for a pass to go into Bethulie. Tant Lettie went to buy extra food. This was all that kept us alive.

I think of the thousands who died in the camps. I thank God that we survived.

In summer 1902, as Kitchener's cordon strangled Boer resistance, Tant Lettie got notice that she and the children were going to another camp.

My mother was too young at the time to know why they had been transferred, whether Tant Lettie's Tommy friend pulled strings or what other reason was behind the move. They went from Bethulie to a camp at Kabusie River near Stutterheim in the Eastern Cape, nestled in the green hills of the Amatola Range, a world away from the horrors of Bethulie.

This time, Johanna recalled making the two-hundred-and-fifty-mile journey in a cattle truck. According to one report, refugees were supplied with tents, which they ingeniously erected on the beds of railroad cars. Others huddled under tarpaulins.

"The former arrived more contented and less sullen. All were provided with hot water and cocoa en route."

Doctors vaccinated us on arrival at Kabusie. Our arms swelled up. Michiel and Johann became sick but after a while we were all OK.

We lived in a one-roomed house with a plank table, plank chairs and three plank beds with straw mattresses.

Our days at Kabusie were happier. Farmers in the district helped the Boers. The camp was small, nothing like Bethulie. I do not recall anyone dying at Kabusie.

A Miss O'Brien taught school in the camp. I learnt English from her. After school, she invited me to her room. My dress was in rags. Miss O'Brien cut up her own clothes to make dresses for me. She taught me how to knit and gave me a ball of wool for a pair of socks.

Who was Miss O'Brien? Was she English or Irish as her name might suggest? Was she one of Emily Hobhouse's angels of mercy? It matters not, just that she was there, sitting with a child pretty as a flower, teaching her to knit a pair of socks.

Today, the site of Kabusie Concentration Camp is a car park, the surface area graveled and curbed.

"The socks were yellow," Johanna said a lifetime later. She never forgot Miss O'Brien's kindness.